Preserved macroscopic polymeric sheets of shell-binding protein in the Middle Miocene (8 to 18 Ma) gastropod Ecphora

Affiliations | Corresponding Author | Cite as | Funding informationKeywords: Protein, shell-binding protein, pigment, Ecphora, Miocene, Calvert Cliffs

- Share this article

-

Article views:10,668Cumulative count of HTML views and PDF downloads.

- Download Citation

- Rights & Permissions

top

Abstract

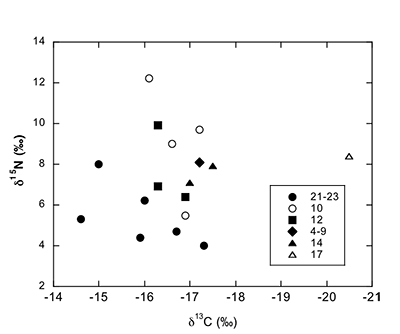

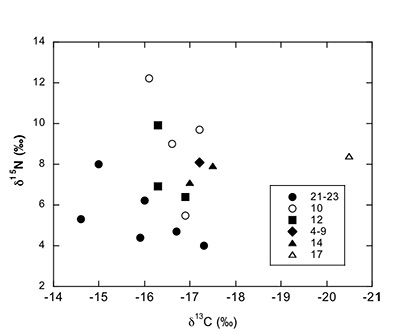

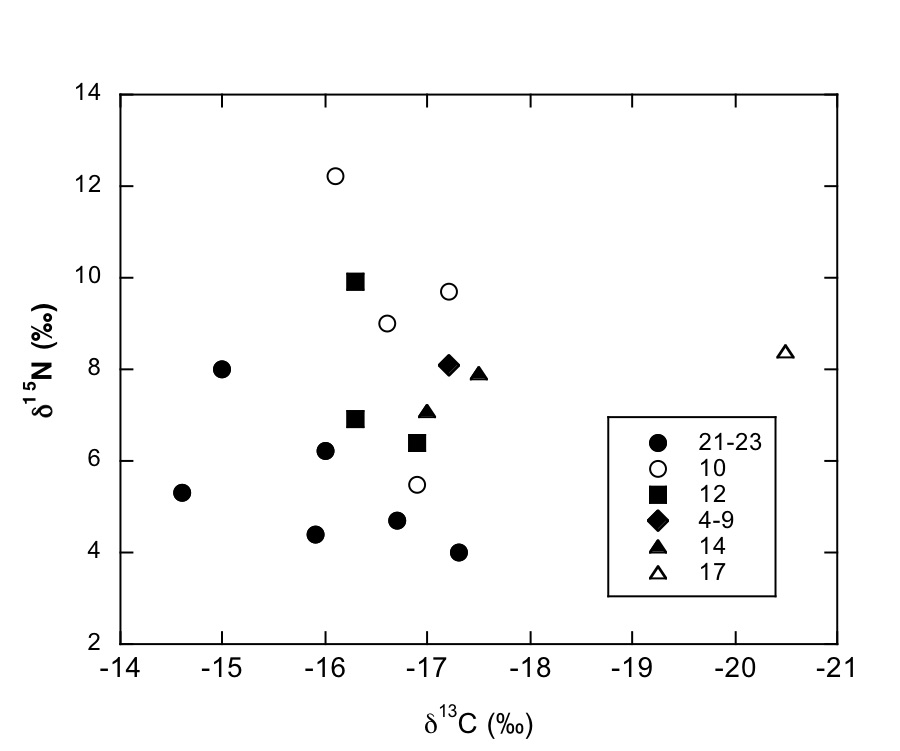

The genus Ecphora of Muricid gastropods from the mid-Miocene Calvert Cliffs, Maryland is characterised by distinct reddish-brown colouration that results from shell-binding proteins associated with pigments within the outer calcite (CaCO3) portion of the shell. The mineral composition and robustness of the shell structure make Ecphora unique among the Neogene gastropods. Acid-dissolved shells produce a polymeric sheet-like organic residue of the same colour as the initial shell. NMR analysis indicates the presence of peptide bonds, while hydrolysis of the polymeric material yields 11 different amino acid residues, including aspartate and glutamate, which are typical of shell-binding proteins. Carbon and nitrogen elemental and isotopic analyses of the organic residue reveals that total organic carbon ranges from 4 to 40 weight %, with 11 < C/Nat < 18. Isotope values for carbon (-17 < δ13C < -15 ‰) are consistent with a shallow marine environment, while values for nitrogen (4 < δ15N < 12.2 ‰) point to Ecphora's position in the trophic structure with higher values indicating predator status. The preservation of the pigmentation and shell-binding proteinaceous material presents a unique opportunity to study the ecology of this important and iconic Chesapeake Bay organism from 8 to 18 million years ago.

The genus Ecphora of Muricid gastropods from the mid-Miocene Calvert Cliffs, Maryland is characterised by distinct reddish-brown colouration that results from shell-binding proteins associated with pigments within the outer calcite (CaCO3) portion of the shell. The mineral composition and robustness of the shell structure make Ecphora unique among the Neogene gastropods. Acid-dissolved shells produce a polymeric sheet-like organic residue of the same colour as the initial shell. NMR analysis indicates the presence of peptide bonds, while hydrolysis of the polymeric material yields 11 different amino acid residues, including aspartate and glutamate, which are typical of shell-binding proteins. Carbon and nitrogen elemental and isotopic analyses of the organic residue reveals that total organic carbon ranges from 4 to 40 weight %, with 11 < C/Nat < 18. Isotope values for carbon (-17 < δ13C < -15 ‰) are consistent with a shallow marine environment, while values for nitrogen (4 < δ15N < 12.2 ‰) point to Ecphora's position in the trophic structure with higher values indicating predator status. The preservation of the pigmentation and shell-binding proteinaceous material presents a unique opportunity to study the ecology of this important and iconic Chesapeake Bay organism from 8 to 18 million years ago.Figures and Tables

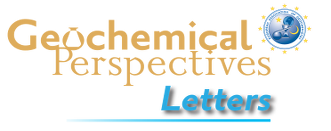

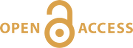

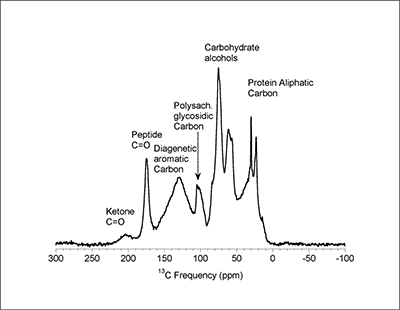

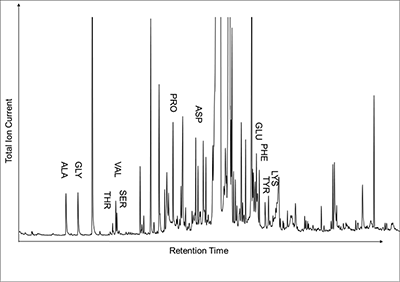

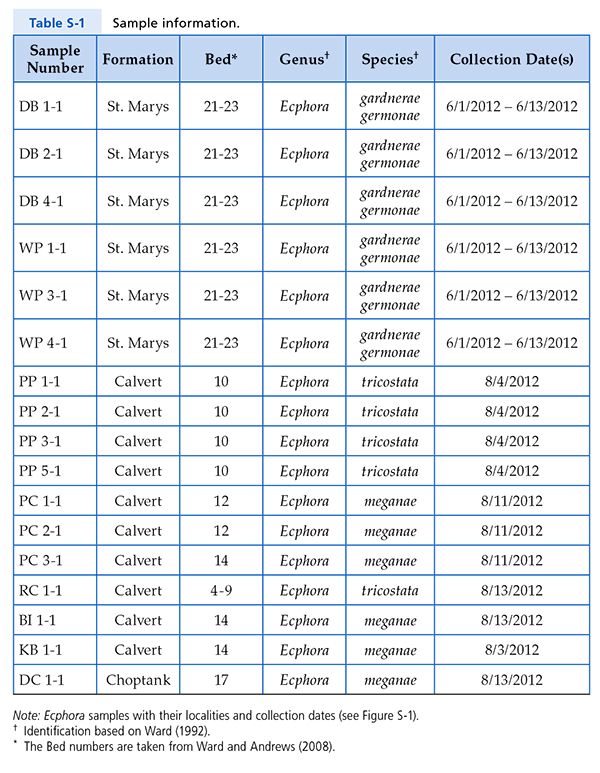

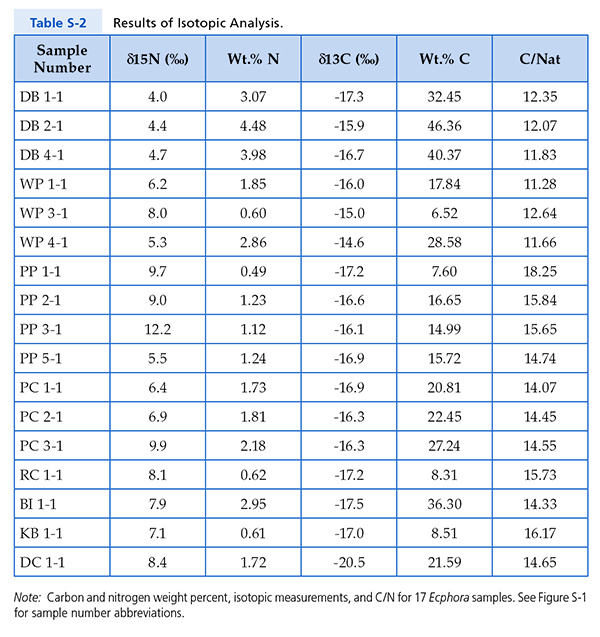

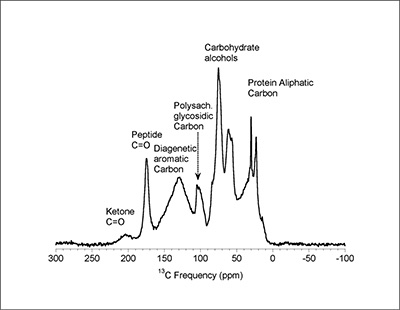

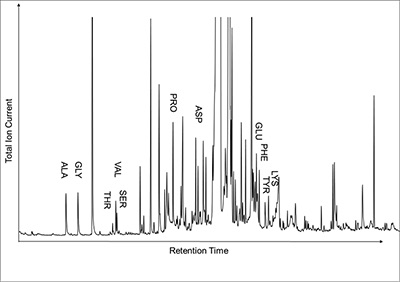

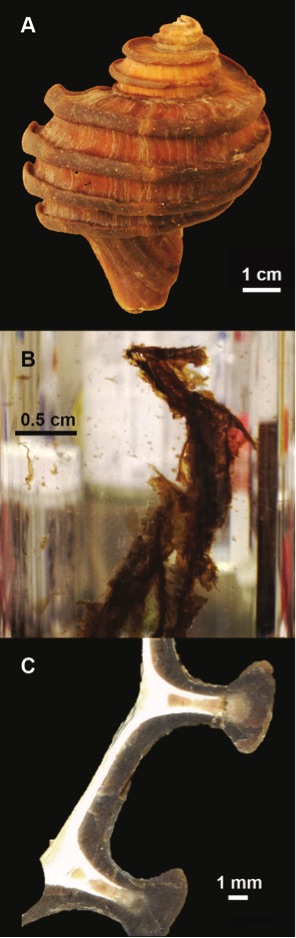

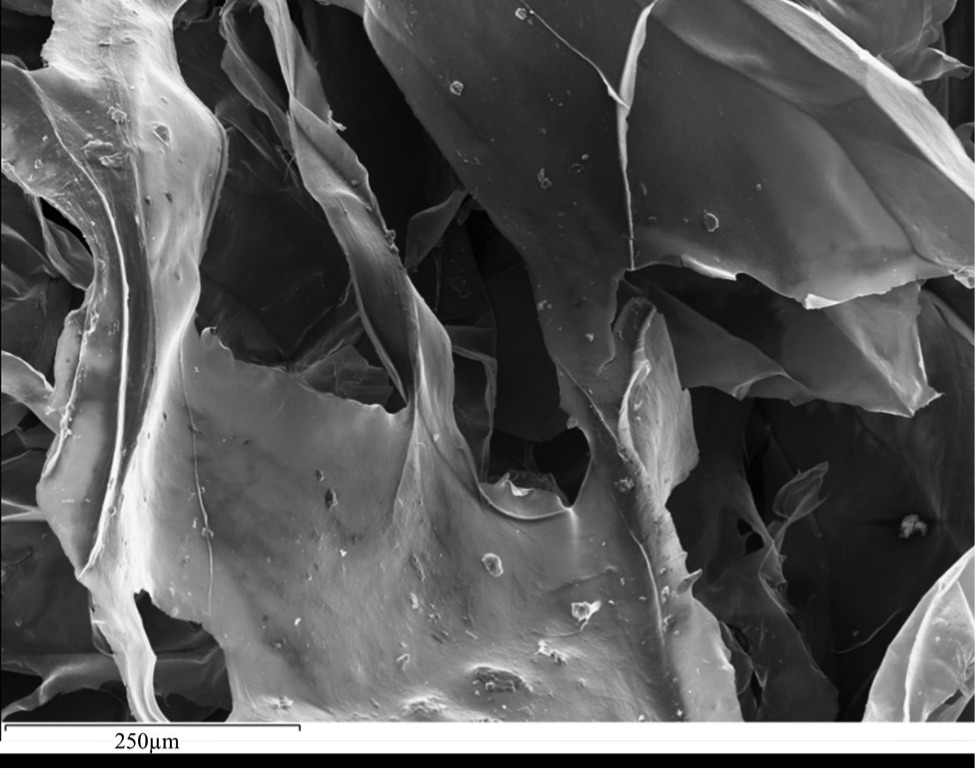

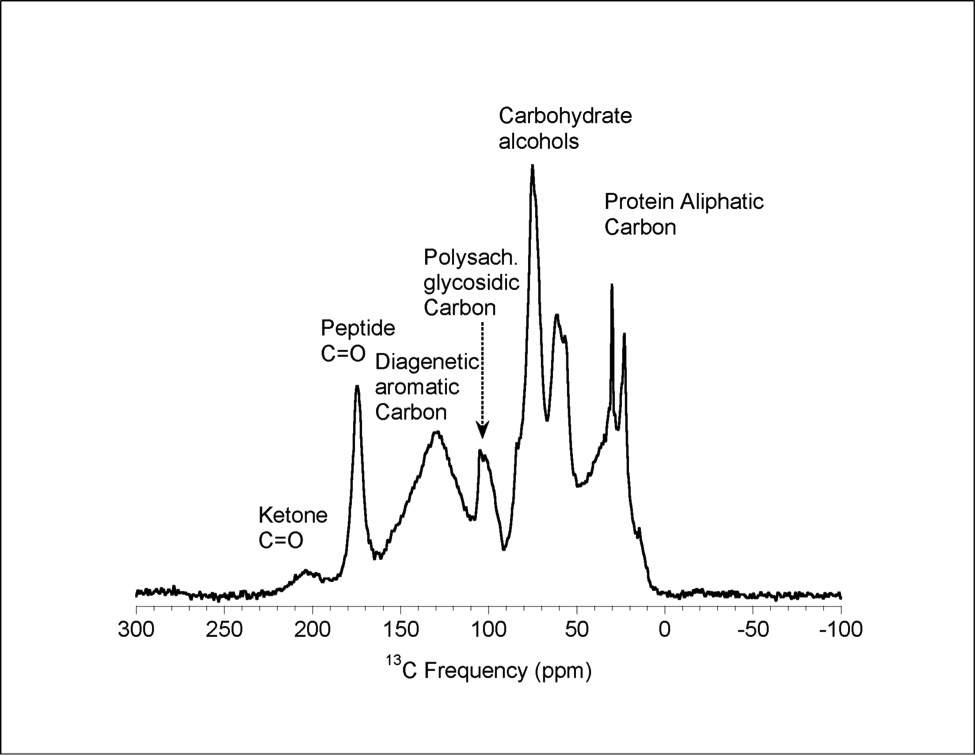

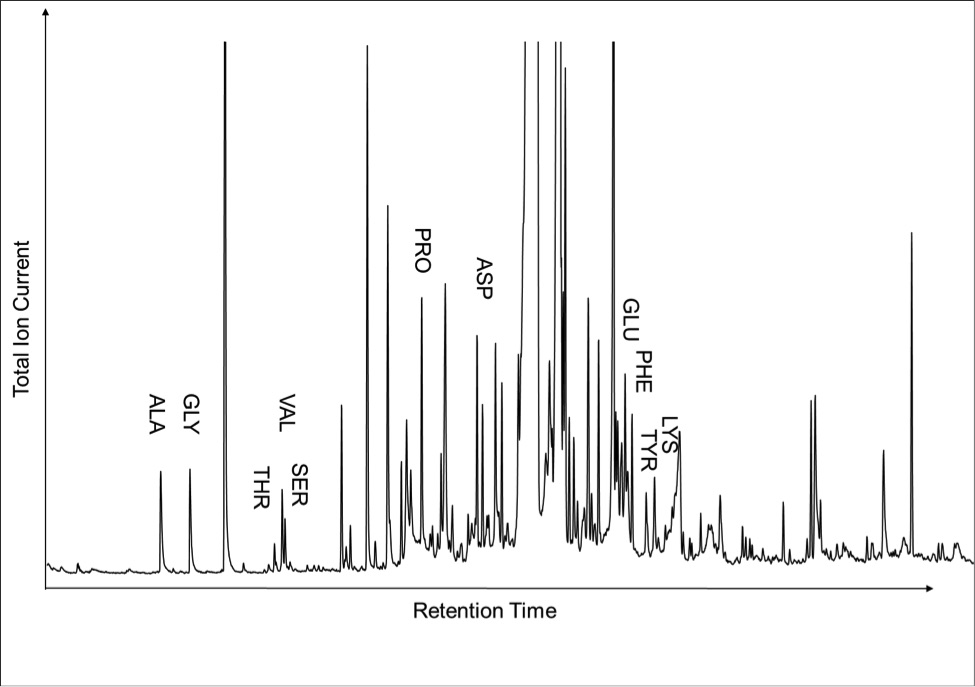

Figure 1 (A) Image showing characteristic colouration and shape of Ecphora gardnerae germonae; St. Marys Formation, Little Cove Point member, Driftwood Beach, Calvert County MD. (B) Polymeric protein-rich residue from the calcitic portions of dissolved Ecphora shell from a St. Marys Formation, Driftwood Beach specimen. This material gives the distinctive colour to the shells. (C) A polished cross-section of two costae from Ecphora gardnerae germonae reveals the colored calcitic outer layer and white aragonitic inner layer. |  Figure 2 Scanning electron micrograph of the polymeric residue from dissolved Ecphora from a St. Marys Formation, Driftwood Beach specimen. The sheets are an estimated 10nm thick. These polymeric sheets represent protein-rich shell-binding organics, which were recovered from calcite shell material dissolved in HCl. |  Figure 3 13C Solid-state Nuclear magnetic resonance spectrum of the organic residue obtained from Ecphora through acid demineralisation. Note that approximately 70 % of the carbon is represented by apparently well preserved protein and polysaccharide. The analysed sample came from the St. Marys Formation. |  Figure 4 A mass chromatogram of the derivitised (to form isopropyl esterified and N-trifluoroacetylated derivatives) products of an acid hydrolysed Ecphora organic residue. In addition to a wide range of small molecules, numerous amino acids are observed derived from hydrolysis of protein associated with the pigmented residue. The analysed sample came from the St. Marys Formation. |

| Figure 1 | Figure 2 | Figure 3 | Figure 4 |

Supplementary Figures and Tables

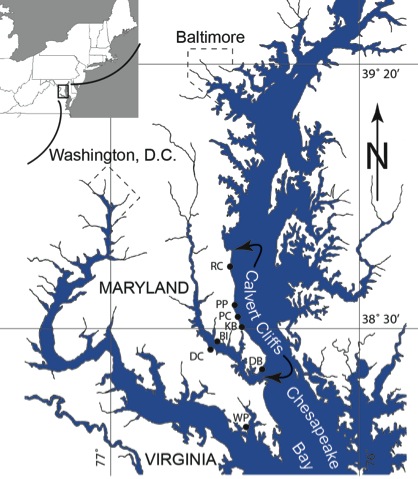

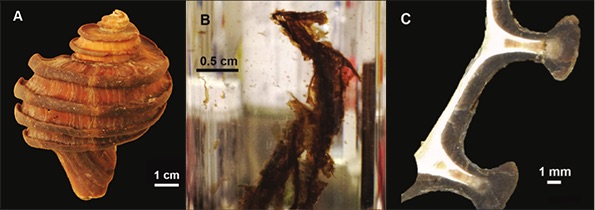

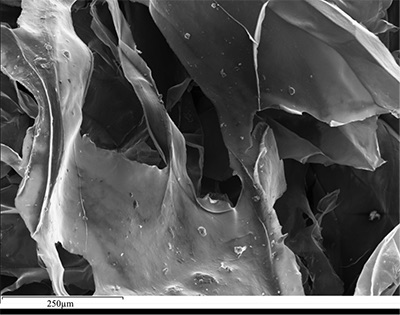

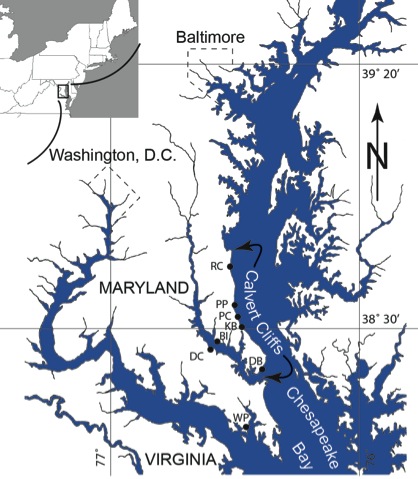

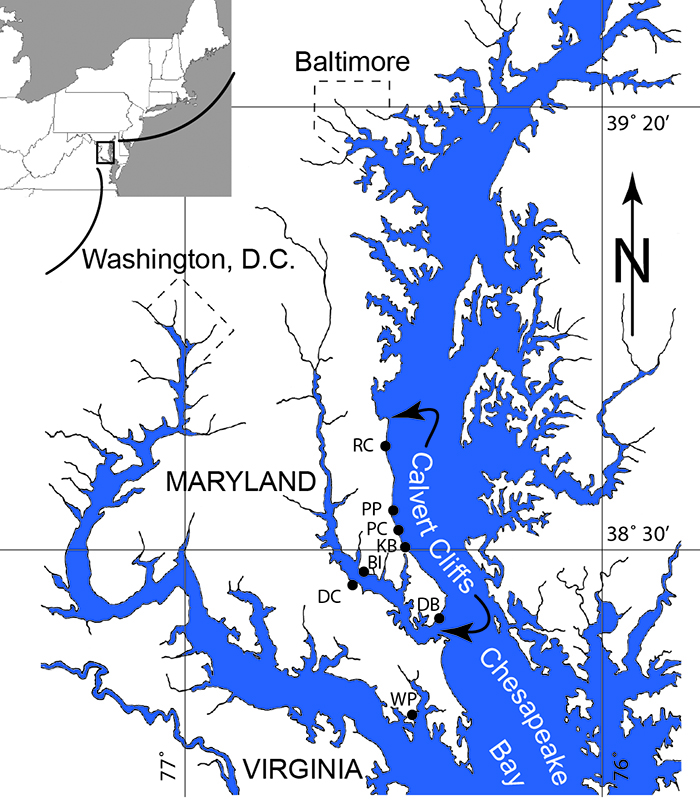

Figure S-1 Map showing locations of Ecphora samples collected (see Table S-1). Drum Cliff (DC), Broomes Island (BI), Kenwood Beach (KB), Randle Cliff (RC), Plum Point (PP), Parkers Creek (PC), Windmill Point (WP), Driftwood Beach (DB). Modified from Visaggi and Godfrey (2010). Visaggi, C.C., Godfrey, S.J. (2010) Variation in composition and abundance of Miocene shark teeth from Calvert Cliffs, Maryland. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 30, 26-35. |  Figure S-2 Carbon and nitrogen isotopes indicate marine environment with terrestrial influence. Additionally they indicate a shift in trophic level over time. Numbers correspond to bed. |  Table S-1 Sample information. |  Table S-2 Results of Isotopic Analysis. |

| Figure S-1 | Figure S-2 | Table S-1 | Table S-2 |

top

Introduction

Ecphora is one of the most distinctive mollusks of the Neogene of North America. It is characterised by striking reddish-brown to tan colouration and typically 3 or 4 prominent costae (Fig. 1A). Ecphora represents an extinct group of Murex gastropods that lived from the late Oligocene to the Pliocene (Carter et al., 1994

Carter, J.G., Rossbach, T.J., Robertson, K.J., Ward, L.W. (1994) Morphological and microstructural evidence for the origin and early evolution of Ecphora (Mollusca: Gastropoda). Journal of Paleontology 68, 905-907.

; Ward and Andrews, 2008Ward, L.W., Andrews, G.W. (2008) Stratigraphy of the Calvert, Choptank, and St. Marys Formations (Miocene) in the Chesapeake Bay Area, Maryland and Virginia. Virginia Museum of Natural History, Memoir No. 9, Martinsville, VA, 170.

). Ecphora in its various species and subspecies span nearly 10 Ma of time along Calvert Cliffs, Maryland within the Calvert, Choptank and St. Marys Formations. This genus is unique in the context of the Calvert Cliffs fauna, in that pronounced colouration is preserved in the sculpted calcitic (CaCO3) outer shell layer, as opposed to the white aragonitic (also CaCO3) nacreous inner shell layer (Fig. 1C). Most other mollusk shells of the Calvert Cliffs are composed principally of aragonite and occur as white chalky shells, or are completely leached out of some beds (Shattuck, 1904Shattuck, G.B. (1904) Geological and paleontological relations, with a review of earlier investigations; the Miocene deposits of Maryland. In: Miocene. Maryland Geological Survey, The Johns Hopkins Press, 1-543.

; Vokes, 1957Vokes, H.E. (1957) Miocene fossils of Maryland, Bulletin 20. Maryland Geological Survey, The Johns Hopkins Press, 1-85.

; Petuch and Drolshagen, 2010Petuch, E.J., Drolshagen, M. (2010) Molluscan Paleontology of the Chesapeake Miocene. CRC Press.

). By contrast, Ecphora found in situ invariably maintains its rich red-brown colour, which fades gradually to light tan when exposed to sunlight. This striking colouration is preserved in specimens as old as 18 Ma and suggests the possibility that biomolecular fossils of shell-binding proteins and associated pigments might be preserved.Protein and polysaccharides are known to be important components of mollusk shell architecture; they form the organic matrix upon which the calcite and/or aragonite crystallises (Marin et al., 2008

Marin, F., Luquet, G., Marie, B., Medakovic, D. (2008) Molluscan shell proteins: Primary structure, origin, and evolution. Current Topics in Developmental Biology 80, 209-276.

; Mann, 2001Mann, S. (2001) Biomineralization: Principles and Concepts in Bioinorganic Materials Chemistry. Oxford University Press, New York.

; Weiner et al., 1984Weiner, S., Traub, W., Parker, S.B. (1984) Macromolecules in mollusc shells and their functions in biomineralization [and Discussion]. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B 304, 425-434.

; Dove, 2010Dove, P.M. (2010) The rise of skeletal biomineralization. Elements 6, 37-42.

). The organic shell-binding matrix forms sheets ~30 nm in thickness between which the minerals crystallise (Mann, 2001)Mann, S. (2001) Biomineralization: Principles and Concepts in Bioinorganic Materials Chemistry. Oxford University Press, New York.

. Mollusks also commonly incorporate carotenoids derived from their diet to add shell pigmentation. Carotenoids are a common class of tetraterpenoid pigments in both plants and animals with the colour arising from conjugated carbon bonds in their C40 hydrocarbon chains (McGraw, 2006McGraw, K.J. (2006) Mechanics of carotenoid-based coloration. In: Hill, G.E., McGraw, K.J. (Eds.) Bird Coloration: Mechanisms and Measurements. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 177-242.

). Carotenoids are reactive and photosensitive molecules as demonstrated by their tendency to fade in the presence of light and oxygen, but they can be stabilised by binding to proteins to make carotenoid-protein complexes (Wade et al., 2009Wade, N.M., Tollenaere, A., Hall, M.R., Degnan, B.M. (2009) Evolution of a Novel Carotenoid-Binding Protein Responsible for Crustacean Shell Color. Molecular Biology and Evolution 26, 1851–1864.

). In this study we characterise organic residues dissolved from Ecphora's outer calcitic shell, including element and isotopic composition and molecular identities.

Figure 1 (A) Image showing characteristic colouration and shape of Ecphora gardnerae germonae; St. Marys Formation, Little Cove Point member, Driftwood Beach, Calvert County MD. (B) Polymeric protein-rich residue from the calcitic portions of dissolved Ecphora shell from a St. Marys Formation, Driftwood Beach specimen. This material gives the distinctive colour to the shells. (C) A polished cross-section of two costae from Ecphora gardnerae germonae reveals the colored calcitic outer layer and white aragonitic inner layer.

Materials and Methods

Specimens studied. Specimens were collected in situ from eroding bluffs from a wide range of stratigraphic and geographic areas in Southern Maryland (Fig. S-1). All fossils are mid-Miocene (8 to 18 Ma) in age from the St. Marys, Choptank and Calvert formations. We examined 17 specimens of several Ecphora species (from beds 4 to 9, 10, 12, 14, 17 and 21 to 23; Table S-1). The beds or zones of Calvert Cliffs were originally designated to further subdivide the formations and members of the Calvert Cliffs sedimentary sequence (Shattuck, 1904

Shattuck, G.B. (1904) Geological and paleontological relations, with a review of earlier investigations; the Miocene deposits of Maryland. In: Miocene. Maryland Geological Survey, The Johns Hopkins Press, pp. 1-543.

).Specimen preparation. Shells were mechanically separated from the matrix and subsequently cleaned using distilled water to remove residual matrix. Calcitic costae, representing the thickest portions of the Ecphora shells (Fig. 1C), were mechanically removed and cleaned, and ~2 g of each shell were placed in a glass vial. Calcite dissolution was achieved with ~60 ml of 10 % HCl leaving behind an organic-rich polymeric residue (Fig. 1B). We ultrasonicated the residue with 20 ml of distilled water three times to de-acidify the solution. We pipetted water from the vials to concentrate the residue, which was then frozen at -19 °C before freeze drying. Two grams of raw shell material yielded 1 to 57 mg of coloured organic residue with an average of ~6 to 8 mg (Fig. 1B).

Scanning electron microscopy. We obtained SEM images and qualitative analyses on fragmental and polished specimens, as well as fragments of the polymeric residue, which were coated with iridium for analysis to prevent interference of carbon and nitrogen detection. We employed a JEOL 6500F SEM with an Oxford silicon drift energy dispersive detector (SDD-EDS). We used a 15 kV, 1 nA beam to obtain secondary electron images and elemental maps. Analyses were uncorrected for irregular specimen morphology so analytical results are semi-quantitative.

NMR analysis. 13C Solid state NMR was performed using a Chemagnetics Infinity Nuclear Magnetic Resonance spectrometer with a magnetic field of 7 Tesla. 1H-13C cross polarisation was performed using a ramped contact pulse amplitude. The 1H excitation (90°) pulse length was 4 µs, the contact time was optimised at 4.5 ms, and high-power 1H decoupling was performed with RF power (ω1/2π) of 65 kHz. Magic angle sample spinning at a frequency (ωR/2π) of 11.5 kHz sufficiently averages the chemical shielding anisotropy and helps minimise 1H-13C dipolar coupling, leading to well resolved 13C solid state NMR spectrum of the Ecphora organic residue. The number of acquisitions was 100,000 with a recycle delay of 1 s. The resultant spectrum is referenced to tetramethyl silane (TMS, defined as 0 ppm).

Amino acid analysis. The Ecphora organic residues were reacted in 6 N HCl at 100 °C for 24 hours to hydrolyse any intact protein to free amino acids. The solutions were separated from unreacted organic residue and dried under N2. Standard derivitisation of amino acids for analysis using GC-MS involved esterification with 2-propanol and acetyl chloride at 110 °C for one hour. The solutions were then evaporated to dryness under N2 to remove unreacted 2-propanol and acetyl chloride. The free amine group was then acylated using trifluoracetic acid in methylene chloride at 110 °C for one hour. Following evaporation to dryness, the derivitised amino acids were resuspended in dichloromethane for analysis using gas chromatography and mass spectrometry (GC-MS).

GC-MS analysis employed an Agilent 6890 gas chromatograph with a 30 metre 5 % phenyl polydimethylsilicone chromatographic column. Compound detection was performed using an Agilent 5973 mass spectrometer. A simple thermal program starting at 50 °C and ramping to 300 °C at a rate of 5 °C/min was sufficient to separate all compounds of interest. The identities of individual amino acids are confirmed based on comparison with their elution times and mass fragmentation with that of pure amino acid standards. No attempt was made to identify many of the unknown molecules present but inspection of the fragment radical cation masses does provide some insight into their origin.

Isotopic analysis. Bulk C and N elemental and isotopic compositions were determined on ~0.2 mg samples loaded into silver or tin capsules of known weight and stored in a dry N2 flushed oven at 50 °C for at least 12 h. All analyses were conducted using a CE Instruments NA 2500 series elemental analyser (EA) linked to a Thermo Fisher Delta V Plus mass spectrometer by Conflo III interface. Samples were introduced directly from an autosampler into the EA, where they were combusted with ultrapure O2 at 1020 °C in a quartz oxidation column containing chromium (III) oxide and silvered cobalt (II, III) oxide. The resulting gases, CO2 and N2 mixed with zero-grade He as the carrier gas, were separated prior to isotopic analysis. Both N2 and CO2 samples were analysed relative to internal working gas standards. Acetanilide (C8H9NO) was analysed at regular intervals to monitor the accuracy of the measured isotopic ratios (±0.2 ‰ for δ13C and ±0.3 ‰ for δ15N) and elemental compositions.

top

Results and Discussion

Results from several analytical techniques are all consistent with the remarkable preservation of protein-rich, polymeric shell-binding material and associated pigments in specimens as old as 18 Ma. Four lines of evidence support this conclusion.

1. Dissolved calcitic portions of Ecphora yield significant amounts (≥ 3 mg per gram) of a polymeric substance with an orange-brown colour similar to that of the in situ fossil shell material. Microscopic and SEM imaging reveals that this residual material forms thin (≤ 30 nm) flexible sheets with maximum dimensions to ~ 1 cm (Fig. 2) - characteristics consistent with modern molluscan shell-binding proteins (Marin et al., 2008

Marin, F., Luquet, G., Marie, B., Medakovic, D. (2008) Molluscan shell proteins: Primary structure, origin, and evolution. Current Topics in Developmental Biology 80, 209-276.

; Mann, 2001Mann, S. (2001) Biomineralization: Principles and Concepts in Bioinorganic Materials Chemistry. Oxford University Press, New York.

; Weiner et al., 1984Weiner, S., Traub, W., Parker, S.B. (1984) Macromolecules in mollusc shells and their functions in biomineralization [and Discussion]. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B 304, 425-434.

; Dove, 2010Dove, P.M. (2010) The rise of skeletal biomineralization. Elements 6, 37-42.

). In addition, SEM images and analyses of broken shell material reveal thin organic sheets visible on fractured surfaces of the calcitic (but not aragonitic) portions of Ecphora shells. All EDS spectra reveal carbon; some spectra also indicate excess carbon from the carbon tape substrate that the samples were adhered to for SEM analysis.

Figure 2 Scanning electron micrograph of the polymeric residue from dissolved Ecphora from a St. Marys Formation, Driftwood Beach specimen. The sheets are an estimated 10 nm thick. These polymeric sheets represent protein-rich shell-binding organic compounds, which were recovered from calcite shell material dissolved in HCl.

Figure 3 13C Solid-state Nuclear magnetic resonance spectrum of the organic residue obtained from Ecphora through acid demineralisation. Note that approximately 70 % of the carbon is represented by apparently well preserved protein and polysaccharide. The analysed sample came from the St. Marys Formation.

Figure 4 A mass chromatogram of the derivitised (to form isopropyl esterified and N-trifluoroacetylated derivatives) products of an acid hydrolysed Ecphora organic residue. In addition to a wide range of small molecules, numerous amino acids are observed derived from hydrolysis of protein associated with the pigmented residue. The analysed sample came from the St. Marys Formation.

Gastropod pigmentation is known to come from a wide range of molecules including melanin, tetropyroles, ommochromes, sclerotin and pterins (Hollingworth and Barker, 1991)

Hollingworth, N.T.J., Barker, M.J. (1991) Colour pattern preservation in the fossil record: Taphonomy and diagenetic significance. In: Donovan, S.K. (Ed.) The Processes of Fossilization. Columbia University Press, New York, 105-119.

. Nevertheless, the presence of carotenoid pigmentation in extant gastropods (Shadidi and Brown, 1998Shadidi, F., Brown, J.A. (1998) Carotenoid pigments in seafoods and aquaculture. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 38, 1-67.

), coupled with the observed photo-sensitivity of the chromophore, is consistent with a protein-bound carontenoid.top

Conclusions

A number of fossil shells and bones have yielded evidence for ancient protein. For example, brachiopod fossils from the Jurassic and Silurian were shown to have some preserved proteinaceous material (Jope, 1967)

Jope, M. (1967) The protein of brachiopod shell-II. Shell protein from fossil articulates: Amino acid composition. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology 20, 601-605.

; Pecten fossils from the Pleistocene through the Jurassic preserved amino acids and proteinaceous material (Akiyama and Wyckoff, 1970)Akiyama, M., Wyckoff, R.W.G. (1970) The total amino acid content of fossil Pecten shells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science of the USA 67, 1097-1100.

; the shell matrix protein, dermatopontin, has been reported from 1,500 year old snail fossils (Sarashina et al., 2008)Sarashina, I., Kunitomo, Y., Iijima, M., Chiba, S., Endo, K. (2008) Preservation of the shell matrix protein dermatopontin in 1500 year old land snail fossils from the Bonin islands. Organic Chemistry 39, 1742-1746.

; and the bone protein, osteocalcin, has been recovered and sequenced from bison fossils more than 55,000 years old (Nielsen-Marsh et al., 2002)Nielsen-Marsh, C.M., Ostrom, P.H., Gandhi, H., Shapiro, B., Cooper, A., Hauschka, P.V., Collins, M.J. (2002) Sequence preservation of osteocalcin protein and mitochondrial DNA in bison bones older than 55 ka. Geology 30, 1099-1102.

. In this context, intact proteinaceous shell-binding material in 8 to 18 Ma Ecphora represents some of the oldest and best-preserved examples of original protein observed in a fossil shell.An important implication of this study is that mineral-bound proteins and amino acids can be effectively protected from degradation. The similar reported preservation of Cretaceous osteocalcin in fossilised dinosaur bone (Muyzer, 1992)

Muyzer, G., Sandberg, P., Knapen, M.H.J., Vermeer, C., Collins, M., Westbroek, P. (1992) Preservation of the Bone Protein Osteocalcin in Dinosaurs. Geology 20, 871-874.

underscores the importance of mineral-molecule interactions in enhancing the stability of otherwise reactive organic molecules. Such protective chemisorption onto mineral surfaces could have played important roles in Earth's near-surface environments since the Hadean Eon and must therefore be considered in any analysis of the possible inventory of prebiotic biomolecules (Hazen, 2006)Hazen, R.M. (2006) Mineral surfaces and the prebiotic selection and organization of biomolecules (Presidential Address to the Mineralogical Society of America). American Mineralogist 91, 1715-1729.

.An exciting opportunity presented by the discovery of intact Miocene shell-binding proteins is the possibility of amino acid sequencing and phylogenetic analysis through 10 million years of gastropod evolution. Similar analysis of bone osteocalcin has been successfully applied to the phylogenetic analyses of North American grazing mammals (Nielsen-Marsh et al., 2002)

Nielsen-Marsh, C.M., Ostrom, P.H., Gandhi, H., Shapiro, B., Cooper, A., Hauschka, P.V., Collins, M.J. (2002) Sequence preservation of osteocalcin protein and mitochondrial DNA in bison bones older than 55 ka. Geology 30, 1099-1102.

. Similar identification and sequencing of Ecphora proteins could provide unprecedented insight into muricid evolution.top

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Roxanne Bowden, Derek Smith and Andrew Steele for technical assistance in the analyses of our samples. We would also like to thank the reviewers for their helpful insights and suggestions. Work was supported in part by the NASA Astrobiology Institute, the Deep Carbon Observatory, the Hazen Foundation, and the Carnegie Institution of Washington.

Editor: Bruce Watson

top

References

Akiyama, M., Wyckoff, R.W.G. (1970) The total amino acid content of fossil Pecten shells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science of the USA 67, 1097-1100.

Show in context

Show in contextPecten fossils from the Pleistocene through the Jurassic preserved amino acids and proteinaceous material (Akiyama and Wyckoff, 1970) View in article

Carter, J.G., Rossbach, T.J., Robertson, K.J., Ward, L.W. (1994) Morphological and microstructural evidence for the origin and early evolution of Ecphora (Mollusca: Gastropoda). Journal of Paleontology 68, 905-907.

Show in context

Show in context

Ecphora represents an extinct group of Murex gastropods that lived from the late Oligocene to the Pliocene (Carter et al., 1994; Ward and Andrews, 2008) View in article

Dove, P.M. (2010) The rise of skeletal biomineralization. Elements 6, 37-42.

Show in context

Show in context

- Protein and polysaccharides are known to be important components of mollusk shell architecture; they form the organic matrix upon which the calcite and/or aragonite crystallises (Marin et al., 2008; Mann, 2001; Weiner et al., 1984; Dove, 2010) View in article

- 1. Dissolved calcitic portions of Ecphora yield significant amounts (≥ 3 mg per gram) of a polymeric substance with an orange-brown colour similar to that of the in situ fossil shell material. Microscopic and SEM imaging reveals that this residual material forms thin (≤ 30 nm) flexible sheets with maximum dimensions to ~ 1 cm (Fig. 2) - characteristics consistent with modern molluscan shell-binding proteins (Marin et al., 2008; Mann, 2001; Weiner et al., 1984; Dove, 2010) View in article

Hazen, R.M. (2006) Mineral surfaces and the prebiotic selection and organization of biomolecules (Presidential Address to the Mineralogical Society of America). American Mineralogist 91, 1715-1729.

Show in context

Show in context

Such protective chemisorption onto mineral surfaces could have played important roles in Earth's near-surface environments since the Hadean Eon and must therefore be considered in any analysis of the possible inventory of prebiotic biomolecules (Hazen, 2006) View in article

Hollingworth, N.T.J., Barker, M.J. (1991) Colour pattern preservation in the fossil record: Taphonomy and diagenetic significance. In: Donovan, S.K. (Ed.) The Processes of Fossilization. Columbia University Press, New York, 105-119.

Show in context

Show in context

Gastropod pigmentation is known to come from a wide range of molecules including melanin, tetropyroles, ommochromes, sclerotin and pterins (Hollingworth and Barker, 1991). View in article

Jope, M. (1967) The protein of brachiopod shell-II. Shell protein from fossil articulates: Amino acid composition. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology 20, 601-605.

Show in context

Show in context

A number of fossil shells and bones have yielded evidence for ancient protein. For example, brachiopod fossils from the Jurassic and Silurian were shown to have some preserved proteinaceous material (Jope, 1967); View in article

Mann, S. (2001) Biomineralization: Principles and Concepts in Bioinorganic Materials Chemistry. Oxford University Press, New York.

Show in context

Show in context

- Protein and polysaccharides are known to be important components of mollusk shell architecture; they form the organic matrix upon which the calcite and/or aragonite crystallises (Marin et al., 2008; Mann, 2001; Weiner et al., 1984; Dove, 2010). View in article

- 1. Dissolved calcitic portions of Ecphora yield significant amounts (≥ 3 mg per gram) of a polymeric substance with an orange-brown colour similar to that of the in situ fossil shell material. Microscopic and SEM imaging reveals that this residual material forms thin (≤ 30 nm) flexible sheets with maximum dimensions to ~ 1 cm (Fig. 2) - characteristics consistent with modern molluscan shell-binding proteins (Marin et al., 2008; Mann, 2001; Weiner et al., 1984; Dove, 2010) View in article

Marin, F., Luquet, G., Marie, B., Medakovic, D. (2008) Molluscan shell proteins: Primary structure, origin, and evolution. Current Topics in Developmental Biology 80, 209-276.

Show in context

Show in context

- Protein and polysaccharides are known to be important components of mollusk shell architecture; they form the organic matrix upon which the calcite and/or aragonite crystallises (Marin et al., 2008; Mann, 2001; Weiner et al., 1984; Dove, 2010) View in article - 1. Dissolved calcitic portions of Ecphora yield significant amounts (≥ 3 mg per gram) of a polymeric substance with an orange-brown colour similar to that of the in situ fossil shell material. Microscopic and SEM imaging reveals that this residual material forms thin (≤ 30 nm) flexible sheets with maximum dimensions to ~ 1 cm (Fig. 2) - characteristics consistent with modern molluscan shell-binding proteins (Marin et al., 2008; Mann, 2001; Weiner et al., 1984; Dove, 2010) View in article

McGraw, K.J. (2006) Mechanics of carotenoid-based coloration. In: Hill, G.E., McGraw, K.J. (Eds.) Bird Coloration: Mechanisms and Measurements. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 177-242.

Show in context

Show in context

Carotenoids are a common class of tetraterpenoid pigments in both plants and animals with the colour arising from conjugated carbon bonds in their C40 hydrocarbon chains (McGraw, 2006) View in article

Muyzer, G., Sandberg, P., Knapen, M.H.J., Vermeer, C., Collins, M., Westbroek, P. (1992) Preservation of the Bone Protein Osteocalcin in Dinosaurs. Geology 20, 871-874.

Show in context

Show in context

An important implication of this study is that mineral-bound proteins and amino acids can be effectively protected from degradation. The similar reported preservation of Cretaceous osteocalcin in fossilised dinosaur bone (Muyzer, 1992) underscores the importance of mineral-molecule interactions in enhancing the stability of otherwise reactive organic molecules. View in article

Nielsen-Marsh, C.M., Ostrom, P.H., Gandhi, H., Shapiro, B., Cooper, A., Hauschka, P.V., Collins, M.J. (2002) Sequence preservation of osteocalcin protein and mitochondrial DNA in bison bones older than 55 ka. Geology 30, 1099-1102.

Show in context

Show in context

- and the bone protein, osteocalcin, has been recovered and sequenced from bison fossils more than 55,000 years old (Nielsen-Marsh et al., 2002). View in article

- An exciting opportunity presented by the discovery of intact Miocene shell-binding proteins is the possibility of amino acid sequencing and phylogenetic analysis through 10 million years of gastropod evolution. Similar analysis of bone osteocalcin has been successfully applied to the phylogenetic analyses of North American grazing mammals (Nielsen-Marsh et al., 2002). View in article

Petuch, E.J., Drolshagen, M. (2010) Molluscan Paleontology of the Chesapeake Miocene. CRC Press.

Show in context

Show in context

Most other mollusk shells of the Calvert Cliffs are composed principally of aragonite and occur as white chalky shells, or are completely leached out of some beds (Shattuck, 1904; Vokes, 1957; Petuch and Drolshagen, 2010). View in article

Sarashina, I., Kunitomo, Y., Iijima, M., Chiba, S., Endo, K. (2008) Preservation of the shell matrix protein dermatopontin in 1500 year old land snail fossils from the Bonin islands. Organic Chemistry 39, 1742-1746.

Show in context

Show in context

the shell matrix protein, dermatopontin, has been reported from 1,500 year old snail fossils (Sarashina et al., 2008); View in article

Shadidi, F., Brown, J.A. (1998) Carotenoid pigments in seafoods and aquaculture. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 38, 1-67.

Show in context

Show in context

Nevertheless, the presence of carotenoid pigmentation in extant gastropods (Shadidi and Brown, 1998), coupled with the observed photo-sensitivity of the chromophore, is consistent with a protein-bound carontenoid. View in article

Shattuck, G.B. (1904) Geological and paleontological relations, with a review of earlier investigations; the Miocene deposits of Maryland. In: Miocene. Maryland Geological Survey, The Johns Hopkins Press, 1-543.

Show in context

Show in context

- Most other mollusk shells of the Calvert Cliffs are composed principally of aragonite and occur as white chalky shells, or are completely leached out of some beds (Shattuck, 1904; Vokes, 1957; Petuch and Drolshagen, 2010). View in article

- The beds or zones of Calvert Cliffs were originally designated to further subdivide the formations and members of the Calvert Cliffs sedimentary sequence (Shattuck, 1904). View in article

Visaggi, C.C., Godfrey, S.J. (2010) Variation in composition and abundance of Miocene shark teeth from Calvert Cliffs, Maryland. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 30, 26-35.

Show in context

Show in context

Map showing locations of Ecphora samples collected (Table S-1). Drum Cliff (DC), Broomes Island (BI), Kenwood Beach (KB), Randle Cliff (RC), Plum Point (PP), Parkers Creek (PC), Windmill Point (WP), Driftwood Beach (DB) (modified from Visaggi and Godfrey, 2010). View in article

Vokes, H.E. (1957) Miocene fossils of Maryland, Bulletin 20. Maryland Geological Survey, The Johns Hopkins Press, 1-85.

Show in context

Show in context

Most other mollusk shells of the Calvert Cliffs are composed principally of aragonite and occur as white chalky shells, or are completely leached out of some beds (Shattuck, 1904; Vokes, 1957; Petuch and Drolshagen, 2010). View in article

Wade, N.M., Tollenaere, A., Hall, M.R., Degnan, B.M. (2009) Evolution of a Novel Carotenoid-Binding Protein Responsible for Crustacean Shell Color. Molecular Biology and Evolution 26, 1851–1864.

Show in context

Show in context

Carotenoids are reactive and photosensitive molecules as demonstrated by their tendency to fade in the presence of light and oxygen, but they can be stabilised by binding to proteins to make carotenoid-protein complexes (Wade et al., 2009). View in article

Ward, L.W. (1992) Molluscan Biostratigraphy of the Miocene, Middle Atlantic Coastal Plain of North America. Virginia Museum of Natural History, Memoir No. 2, Martinsville, VA, 159.

Show in context

Show in context

Table S-1 Sample information.

Note: Ecphora samples with their localities and collection dates (Fig. S-1). †Identification based on Ward (1992) *The bed numbers are taken from Ward and Andrews (2008). View in article

Ward, L.W., Andrews, G.W. (2008) Stratigraphy of the Calvert, Choptank, and St. Marys Formations (Miocene) in the Chesapeake Bay Area, Maryland and Virginia. Virginia Museum of Natural History, Memoir No. 9, Martinsville, VA, 170.

Show in context

Show in context

- Ecphora represents an extinct group of Murex gastropods that lived from the late Oligocene to the Pliocene (Carter et al., 1994; Ward and Andrews, 2008). View in article

- Table S-1 Sample information.

Note: Ecphora samples with their localities and collection dates (Fig. S-1). †Identification based on Ward (1992) *The bed numbers are taken from Ward and Andrews (2008). View in article

Weiner, S., Traub, W., Parker, S.B. (1984) Macromolecules in mollusc shells and their functions in biomineralization [and Discussion]. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B 304, 425-434.

Show in context

Show in context

- Protein and polysaccharides are known to be important components of mollusk shell architecture; they form the organic matrix upon which the calcite and/or aragonite crystallises (Marin et al., 2008; Mann, 2001; Weiner et al., 1984; Dove, 2010) View in article - 1. Dissolved calcitic portions of Ecphora yield significant amounts (≥ 3 mg per gram) of a polymeric substance with an orange-brown colour similar to that of the in situ fossil shell material. Microscopic and SEM imaging reveals that this residual material forms thin (≤ 30 nm) flexible sheets with maximum dimensions to ~ 1 cm (Fig. 2) - characteristics consistent with modern molluscan shell-binding proteins (Marin et al., 2008; Mann, 2001; Weiner et al., 1984; Dove, 2010) View in article

top

Supplementary Information

Figure S-1 Map showing locations of Ecphora samples collected (Table S-1). Drum Cliff (DC), Broomes Island (BI), Kenwood Beach (KB), Randle Cliff (RC), Plum Point (PP), Parkers Creek (PC), Windmill Point (WP), Driftwood Beach (DB) (modified from Visaggi and Godfrey, 2010)

Visaggi, C.C., Godfrey, S.J. (2010) Variation in composition and abundance of Miocene shark teeth from Calvert Cliffs, Maryland. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 30, 26-35.

.

Figure S-2 Carbon and nitrogen isotopes indicate a marine environment with terrestrial influence. They can also indicate a shift in trophic level over time. Numbers correspond to bed.

Table S-1 Sample information.

Note: Ecphora samples with their localities and collection dates (Fig. S-1). †Identification based on Ward (1992)

Ward, L.W. (1992) Molluscan Biostratigraphy of the Miocene, Middle Atlantic Coastal Plain of North America. Virginia Museum of Natural History, Memoir No. 2, Martinsville, VA, 159.

. *The bed numbers are taken from Ward and Andrews (2008)Ward, L.W., Andrews, G.W. (2008) Stratigraphy of the Calvert, Choptank, and St. Marys Formations (Miocene) in the Chesapeake Bay Area, Maryland and Virginia. Virginia Museum of Natural History, Memoir No. 9, Martinsville, VA, 170.

.| Sample Number | Formation | Bed* | Genus† | Species† | Collection Date(s) |

| DB 1-1 | St. Marys | 21-23 | Ecphora | gardnerae germonae | 6/1/2012 - 6/13/2012 |

| DB 2-1 | St. Marys | 21-23 | Ecphora | gardnerae germonae | 6/1/2012 - 6/13/2012 |

| DB 4-1 | St. Marys | 21-23 | Ecphora | gardnerae germonae | 6/1/2012 - 6/13/2012 |

| WP 1-1 | St. Marys | 21-23 | Ecphora | gardnerae germonae | 6/1/2012 - 6/13/2012 |

| WP 3-1 | St. Marys | 21-23 | Ecphora | gardnerae germonae | 6/1/2012 - 6/13/2012 |

| WP 4-1 | St. Marys | 21-23 | Ecphora | gardnerae germonae | 6/1/2012 - 6/13/2012 |

| PP 1-1 | Calvert | 10 | Ecphora | tricostata | 04/08/2012 |

| PP 2-1 | Calvert | 10 | Ecphora | tricostata | 04/08/2012 |

| PP 3-1 | Calvert | 10 | Ecphora | tricostata | 04/08/2012 |

| PP 5-1 | Calvert | 10 | Ecphora | tricostata | 04/08/2012 |

| PC 1-1 | Calvert | 12 | Ecphora | meganae | 11/08/2012 |

| PC 2-1 | Calvert | 12 | Ecphora | meganae | 11/08/2012 |

| PC 3-1 | Calvert | 14 | Ecphora | meganae | 11/08/2012 |

| RC 1-1 | Calvert | 09/04/2015 | Ecphora | tricostata | 13/08/2012 |

| BI 1-1 | Calvert | 14 | Ecphora | meganae | 13/08/2012 |

| KB 1-1 | Calvert | 14 | Ecphora | meganae | 03/08/2012 |

| DC 1-1 | Choptank | 17 | Ecphora | meganae | 13/08/2012 |

Table S-2 Results of Isotopic Analysis.

Note: Carbon and nitrogen weight percent, isotopic measurements, and C/N for 17 Ecphora samples. See Figure S-1 for sample number abbreviations.

| Sample Number | δ15N (‰) | Wt.% N | δ13C (‰) | Wt.% C | C/Nat |

| DB 1-1 | 4 | 3.07 | -17.3 | 32.45 | 12.35 |

| DB 2-1 | 4.4 | 4.48 | -15.9 | 46.36 | 12.07 |

| DB 4-1 | 4.7 | 3.98 | -16.7 | 40.37 | 11.83 |

| WP 1-1 | 6.2 | 1.85 | -16 | 17.84 | 11.28 |

| WP 3-1 | 8 | 0.6 | -15 | 6.52 | 12.64 |

| WP 4-1 | 5.3 | 2.86 | -14.6 | 28.58 | 11.66 |

| PP 1-1 | 9.7 | 0.49 | -17.2 | 7.6 | 18.25 |

| PP 2-1 | 9 | 1.23 | -16.6 | 16.65 | 15.84 |

| PP 3-1 | 12.2 | 1.12 | -16.1 | 14.99 | 15.65 |

| PP 5-1 | 5.5 | 1.24 | -16.9 | 15.72 | 14.74 |

| PC 1-1 | 6.4 | 1.73 | -16.9 | 20.81 | 14.07 |

| PC 2-1 | 6.9 | 1.81 | -16.3 | 22.45 | 14.45 |

| PC 3-1 | 9.9 | 2.18 | -16.3 | 27.24 | 14.55 |

| RC 1-1 | 8.1 | 0.62 | -17.2 | 8.31 | 15.73 |

| BI 1-1 | 7.9 | 2.95 | -17.5 | 36.3 | 14.33 |

| KB 1-1 | 7.1 | 0.61 | -17 | 8.51 | 16.17 |

| DC 1-1 | 8.4 | 1.72 | -20.5 | 21.59 | 14.65 |

Figures and Tables

Figure 1 (A) Image showing characteristic colouration and shape of Ecphora gardnerae germonae; St. Marys Formation, Little Cove Point member, Driftwood Beach, Calvert County MD. (B) Polymeric protein-rich residue from the calcitic portions of dissolved Ecphora shell from a St. Marys Formation, Driftwood Beach specimen. This material gives the distinctive colour to the shells. (C) A polished cross-section of two costae from Ecphora gardnerae germonae reveals the colored calcitic outer layer and white aragonitic inner layer.

Figure 2 Scanning electron micrograph of the polymeric residue from dissolved Ecphora from a St. Marys Formation, Driftwood Beach specimen. The sheets are an estimated 10nm thick. These polymeric sheets represent protein-rich shell-binding organics, which were recovered from calcite shell material dissolved in HCl.

Figure 3 13C Solid-state Nuclear magnetic resonance spectrum of the organic residue obtained from Ecphora through acid demineralisation. Note that approximately 70 % of the carbon is represented by apparently well preserved protein and polysaccharide. The analysed sample came from the St. Marys Formation.

Figure 4 A mass chromatogram of the derivitised (to form isopropyl esterified and N-trifluoroacetylated derivatives) products of an acid hydrolysed Ecphora organic residue. In addition to a wide range of small molecules, numerous amino acids are observed derived from hydrolysis of protein associated with the pigmented residue. The analysed sample came from the St. Marys Formation.

Back to article

Supplementary Figures and Tables

Figure S-1 Map showing locations of Ecphora samples collected (Table S-1). Drum Cliff (DC), Broomes Island (BI), Kenwood Beach (KB), Randle Cliff (RC), Plum Point (PP), Parkers Creek (PC), Windmill Point (WP), Driftwood Beach (DB) (modified from Visaggi and Godfrey, 2010).

Figure S-2 Carbon and nitrogen isotopes indicate a marine environment with terrestrial influence. They can also indicate a shift in trophic level over time. Numbers correspond to bed.

Table S-1 Sample information.

Note: Ecphora samples with their localities and collection dates (Fig. S-1). †Identification based on Ward (1992)

Ward, L.W. (1992) Molluscan Biostratigraphy of the Miocene, Middle Atlantic Coastal Plain of North America. Virginia Museum of Natural History, Memoir No. 2, Martinsville, VA, pp. 159.

. *The bed numbers are taken from Ward and Andrews (2008)Ward, L.W., Andrews, G.W. (2008) Stratigraphy of the Calvert, Choptank, and St. Marys Formations (Miocene) in the Chesapeake Bay Area, Maryland and Virginia. Virginia Museum of Natural History, Memoir No. 9, Martinsville, VA, pp. 170.

.| Sample Number | Formation | Bed* | Genus† | Species† | Collection Date(s) |

| DB 1-1 | St. Marys | 21-23 | Ecphora | gardnerae germonae | 6/1/2012 - 6/13/2012 |

| DB 2-1 | St. Marys | 21-23 | Ecphora | gardnerae germonae | 6/1/2012 - 6/13/2012 |

| DB 4-1 | St. Marys | 21-23 | Ecphora | gardnerae germonae | 6/1/2012 - 6/13/2012 |

| WP 1-1 | St. Marys | 21-23 | Ecphora | gardnerae germonae | 6/1/2012 - 6/13/2012 |

| WP 3-1 | St. Marys | 21-23 | Ecphora | gardnerae germonae | 6/1/2012 - 6/13/2012 |

| WP 4-1 | St. Marys | 21-23 | Ecphora | gardnerae germonae | 6/1/2012 - 6/13/2012 |

| PP 1-1 | Calvert | 10 | Ecphora | tricostata | 04/08/2012 |

| PP 2-1 | Calvert | 10 | Ecphora | tricostata | 04/08/2012 |

| PP 3-1 | Calvert | 10 | Ecphora | tricostata | 04/08/2012 |

| PP 5-1 | Calvert | 10 | Ecphora | tricostata | 04/08/2012 |

| PC 1-1 | Calvert | 12 | Ecphora | meganae | 11/08/2012 |

| PC 2-1 | Calvert | 12 | Ecphora | meganae | 11/08/2012 |

| PC 3-1 | Calvert | 14 | Ecphora | meganae | 11/08/2012 |

| RC 1-1 | Calvert | 09/04/2015 | Ecphora | tricostata | 13/08/2012 |

| BI 1-1 | Calvert | 14 | Ecphora | meganae | 13/08/2012 |

| KB 1-1 | Calvert | 14 | Ecphora | meganae | 03/08/2012 |

| DC 1-1 | Choptank | 17 | Ecphora | meganae | 13/08/2012 |

Table S-2 Results of Isotopic Analysis.

Note: Carbon and nitrogen weight percent, isotopic measurements, and C/N for 17 Ecphora samples. See Figure S-1 for sample number abbreviations.

| Sample Number | δ15N (‰) | Wt.% N | δ13C (‰) | Wt.% C | C/Nat |

| DB 1-1 | 4 | 3.07 | -17.3 | 32.45 | 12.35 |

| DB 2-1 | 4.4 | 4.48 | -15.9 | 46.36 | 12.07 |

| DB 4-1 | 4.7 | 3.98 | -16.7 | 40.37 | 11.83 |

| WP 1-1 | 6.2 | 1.85 | -16 | 17.84 | 11.28 |

| WP 3-1 | 8 | 0.6 | -15 | 6.52 | 12.64 |

| WP 4-1 | 5.3 | 2.86 | -14.6 | 28.58 | 11.66 |

| PP 1-1 | 9.7 | 0.49 | -17.2 | 7.6 | 18.25 |

| PP 2-1 | 9 | 1.23 | -16.6 | 16.65 | 15.84 |

| PP 3-1 | 12.2 | 1.12 | -16.1 | 14.99 | 15.65 |

| PP 5-1 | 5.5 | 1.24 | -16.9 | 15.72 | 14.74 |

| PC 1-1 | 6.4 | 1.73 | -16.9 | 20.81 | 14.07 |

| PC 2-1 | 6.9 | 1.81 | -16.3 | 22.45 | 14.45 |

| PC 3-1 | 9.9 | 2.18 | -16.3 | 27.24 | 14.55 |

| RC 1-1 | 8.1 | 0.62 | -17.2 | 8.31 | 15.73 |

| BI 1-1 | 7.9 | 2.95 | -17.5 | 36.3 | 14.33 |

| KB 1-1 | 7.1 | 0.61 | -17 | 8.51 | 16.17 |

| DC 1-1 | 8.4 | 1.72 | -20.5 | 21.59 | 14.65 |