Oxygenation of the mid-Proterozoic atmosphere: clues from chromium isotopes in carbonates

Affiliations | Corresponding Author | Cite as- Share this article

-

Article views:18,448Cumulative count of HTML views and PDF downloads.

- Download Citation

- Rights & Permissions

Abstract

Figures and Tables

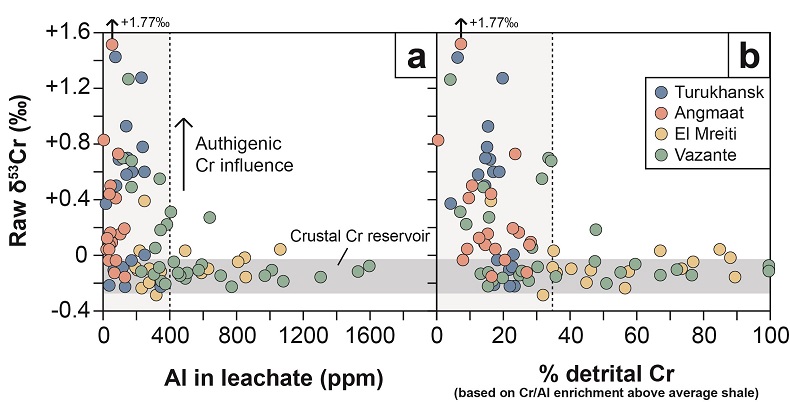

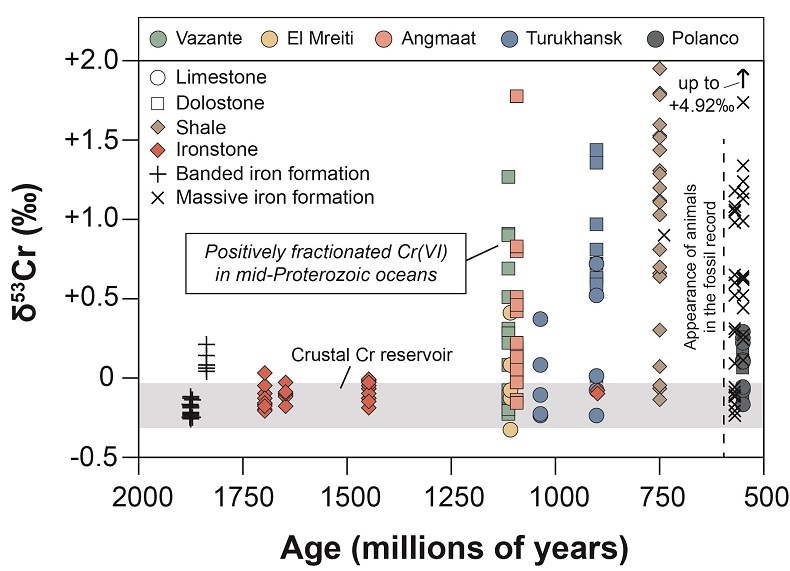

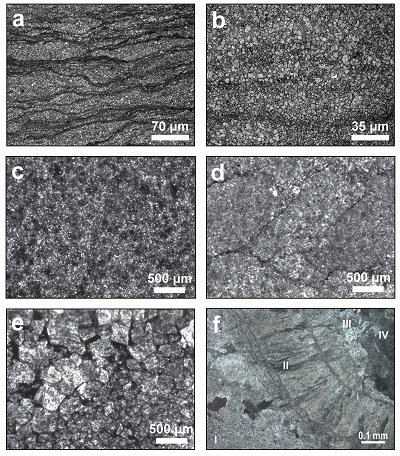

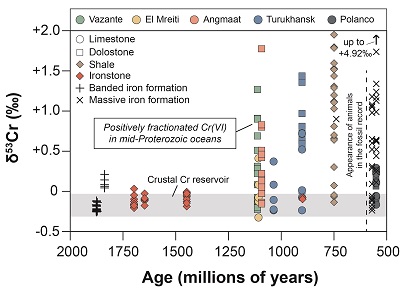

Figure 1 (a) Cross-plot of raw Cr-isotope values and Al concentration in the leachate. Dashed line is at 400 ppm Al. (b) Cross-plot of raw Cr-isotope values and % detrital Cr based on enrichment above average shale. Dashed line is at 35 %. |  Figure 2 Compilation of all published Proterozoic Cr-isotope data including new data presented here. δ53Crauth values (after detrital correction) are presented for data from this study. |

| Figure 1 | Figure 2 |

Supplementary Figures and Tables

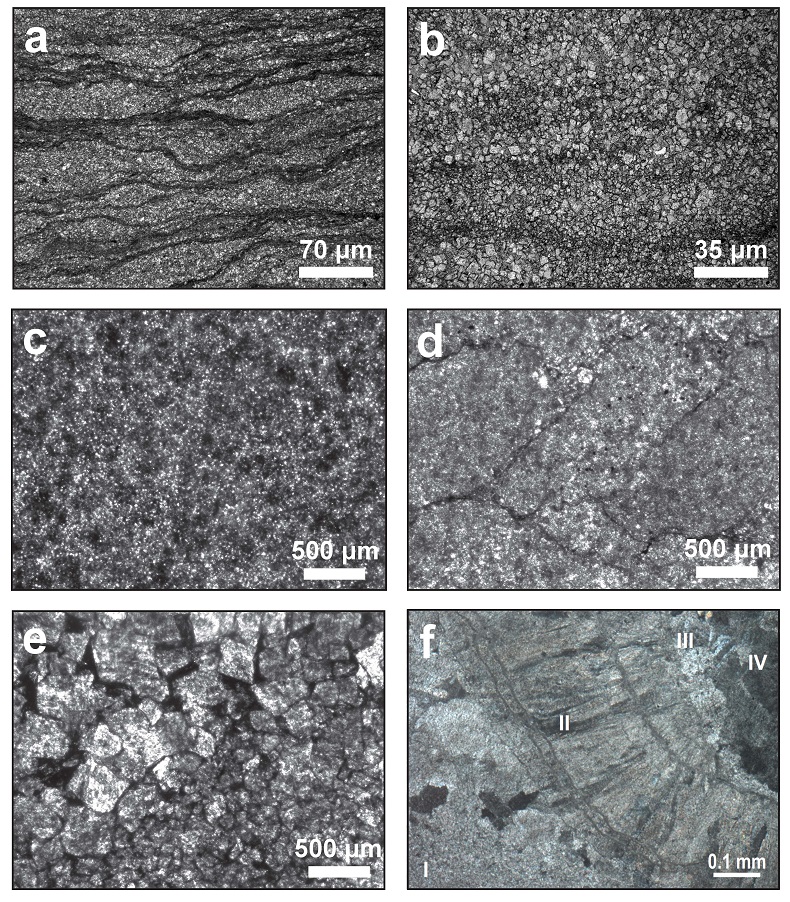

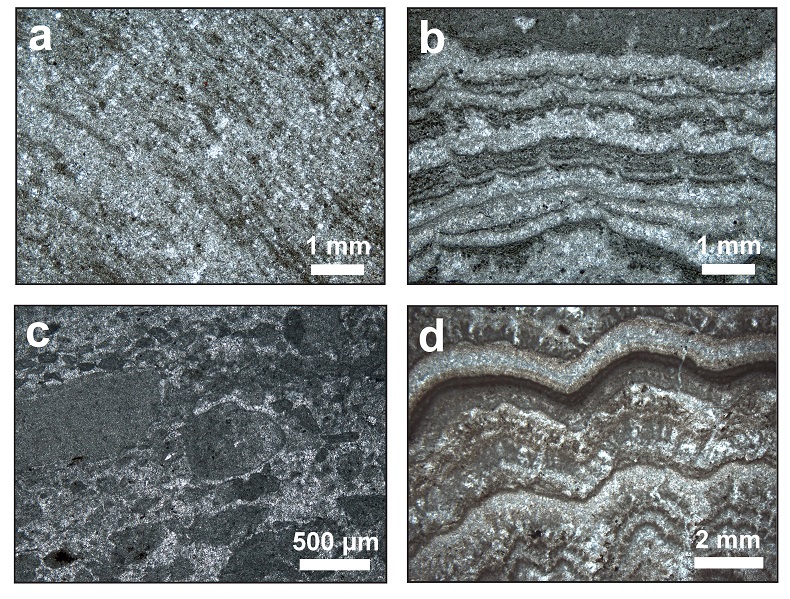

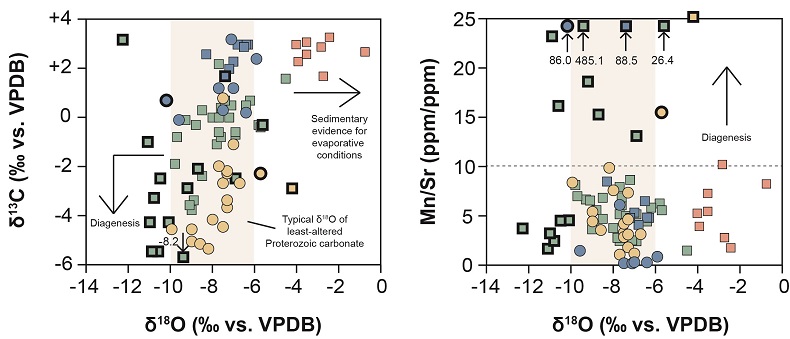

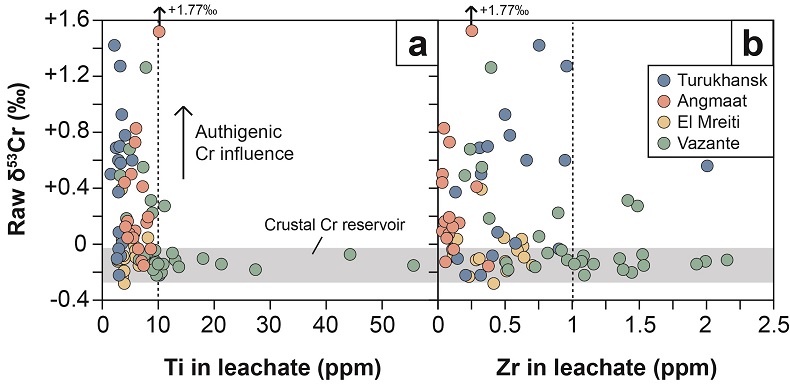

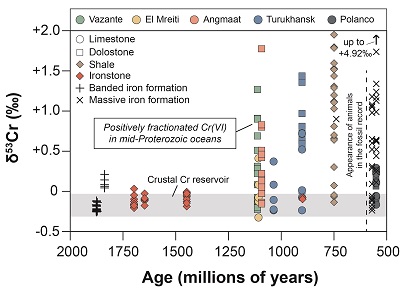

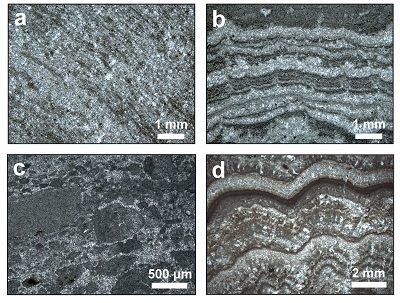

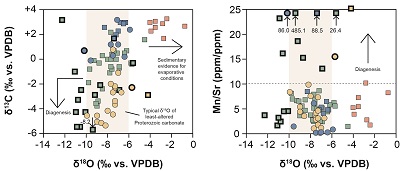

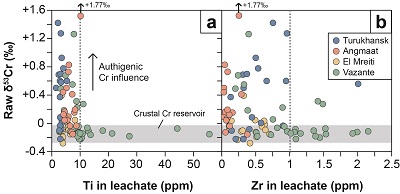

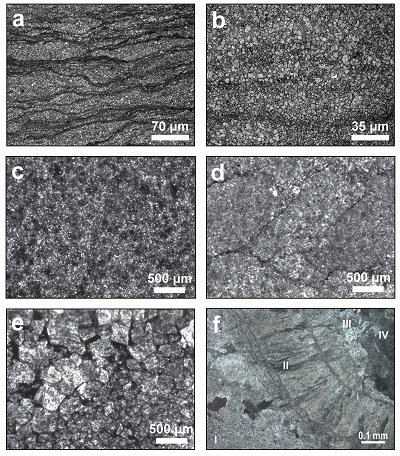

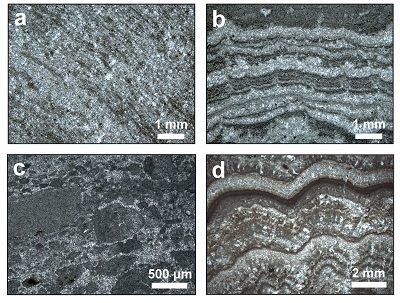

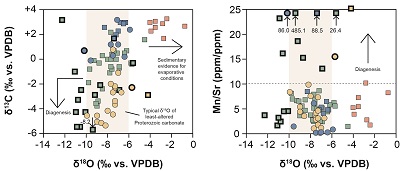

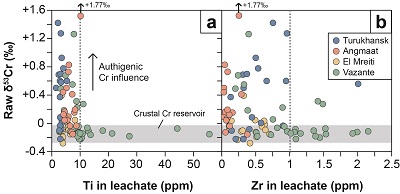

Figure S-1 Photomicrographs highlighting specific textural features in the (a,b) El Mreiti Group, (c,d,e) Turukhansk Uplift, and (f) Vazante Group. (a) Typical micritic limestone of the Touirist Formation. (b) Interval of fabric-destructive dolomitisation in the En Nesoar Formation. (c) Typical clotted micritic limestone of the Miroyedikha Formation. (d) Stylolitised and partially recrystallised intraclasts from the Miroyedikha Formation. (e) Coarse dolomitic spar filling inter-stromatolitic voids in the Miroyedikha Formation. (f) Fine-grained fabric-retentive dolomite (I) of the Lapa Formation (Vazante Group) surrounded by multiple stages (II, III, IV) of later dolomitic cements (>80 % by volume of the Lapa Formation consists of phase I dolomite). |  Figure S-2 Photomicrographs highlighting textural characteristics of the Angmaat Formation. A variety of primary depositional fabrics have been preserved through early dolomitisation, including evapourative features and tepee structures, a storm microbreccia, and microbial mats. |  Figure S-3 Geochemical indicators of diagenesis in all four sections. Circles are limestone and squares are dolostone. Bolded points represent samples that were excluded from further discussion based on diagenetic criteria. Blue = Turukhansk, red = Angmaat, tan = El Mreiti, and green = Vazante. |  Figure S-4 Cross-plots of raw Cr-isotope values vs. other detrital indicators (Ti and Zr). Dashed lines represent 10 ppm Ti and 1 ppm Zr, which seem to be the cutoff values above which detrital Cr masks the authigenic Cr-isotope signal. |

| Figure S-1 | Figure S-2 | Figure S-3 | Figure S-4 |

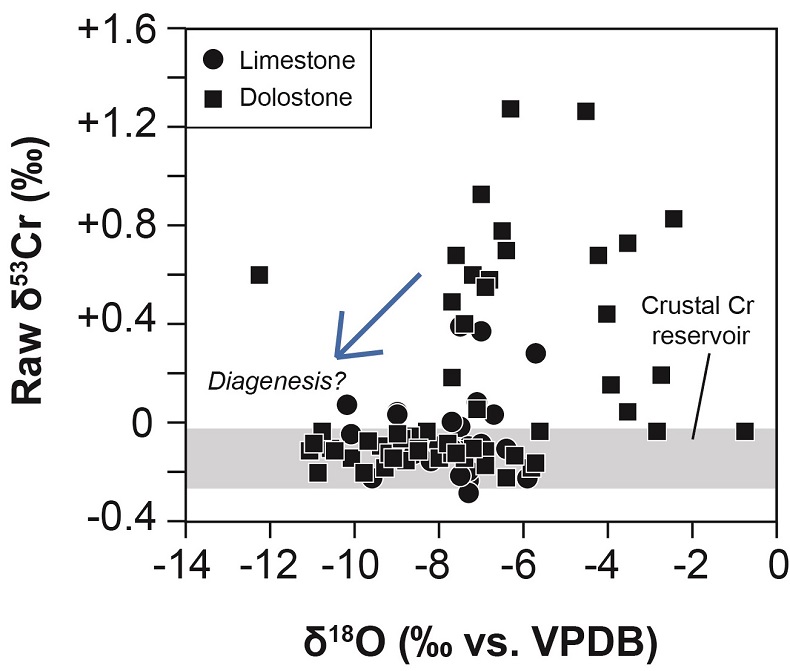

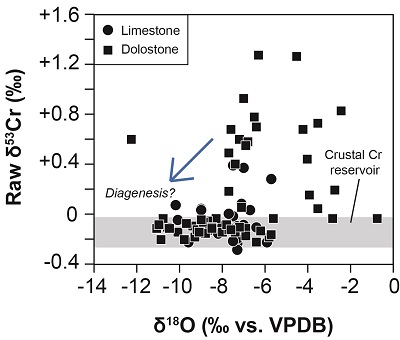

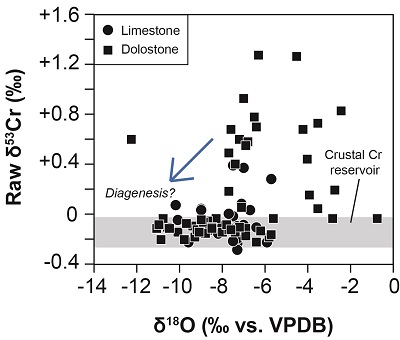

Figure S-5 Cross-plot of raw Cr-isotope values and O-isotopes indicating that lower O-isotope values (potentially indicating diagenesis) correspond to unfractionated Cr-isotope values. This could mean that diagenetic alteration (at least in the case of the Vazante Group) has the potential to reset Cr-isotopes to crustal values. |  Table S-1 Sample information, mineralogy, Cr-isotope, and Al concentration data for carbonates from the Turukhansk Uplift, Vazante and El Mreiti groups, and the Angmaat Formation (~1.1 to 0.9 Ga). |  Table S-2 δ13C, δ18O, major and trace element data, as well as sedimentary environments for the Turukhansk Uplift, Vazante and El Mreiti groups, and the Angmaat Formation (~1.1 to 0.9 Ga). |

| Figure S-5 | Table S-1 | Table S-2 |

top

Introduction

The chromium (Cr) isotope system functions as an atmospheric redox proxy because oxidative weathering of crustal Cr(III)-bearing minerals results in the release of 53Cr-enriched mobile Cr(VI) to solution. Cr(VI) (dominantly as chromate; CrO4-) is then carried to the oceans via rivers, thus imparting a positively fractionated δ53Cr signal on modern seawater (+0.41 to +1.55 ‰ compared to crustal values of –0.123 ± 0.102 ‰) (Schoenberg et al., 2008

Schoenberg, S., Zink, M., Staubwasser, M., von Blanckenburg, F. (2008) The stable Cr isotope inventory of solid Earth reservoirs determine by double spike MC-ICP-MS. Chemical Geology 249, 294-306.

; Bonnand et al., 2013Bonnand, P., James, R.H., Parkinson, I.J., Connelly, D.P., Fairchild, I.J. (2013) The chromium isotopic composition of seawater and marine carbonates. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 382, 10-20.

; Scheiderich et al., 2015Scheiderich, K., Amini, M., Holmden, C., Francois, R. (2015) Global variability of chromium isotopes in seawater demonstrated by Pacific, Atlantic, and Arctic Ocean samples. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 423, 87-97.

). Terrestrial Cr(III)-oxidation occurs by reaction with manganese (Mn) oxides, and it is thought that Mn-oxide formation requires a threshold level of O2 in the atmosphere. Frei et al. (2016)Frei, R., Crowe, S.A., Bau, M., Polat, A., Fowle, D.A., Døssing, L.N. (2016) Oxidative elemental cycling under the low O2 Eoarchean atmosphere. Scientific Reports 6, 21058.

suggested that Cr-oxidation by Mn-oxides is thermodynamically possible at pO2 as low as 10-5 of the present atmospheric level (PAL). Kinetic considerations dictate, however, that 0.1 to 1 % PAL is necessary to oxidise Cr(III) within typical soil residence times (Planavsky et al., 2014Planavsky, N.J., Reinhard, C.T., Wang, X., Thomson, D., McGoldrick, P., Rainbird, R.H., Johnson, T., Fischer, W.W., Lyons, T.W. (2014) Low mid-Proterozoic atmospheric oxygen levels and the delayed rise of animals. Science 346, 635-638.

) and between 0.03 and 0.3 % PAL is necessary to export Cr without re-reduction by Fe(II) (Crowe et al., 2013Crowe, S.A., Døssing, L.N., Beukes, N.J., Bau, M., Kruger, S.J., Frei, R., Canfield, D.E. (2013) Atmospheric oxygenation three billion years ago. Nature 501, 535-538.

). Because the delivery of positively fractionated Cr(VI) to seawater is dependent on a threshold level of atmospheric oxygen, the Cr-isotope composition of seawater through time – as recorded in marine sedimentary rocks – can serve as a sensitive indicator of ancient atmospheric pO2. This is particularly useful for testing hypotheses about atmospheric oxygenation during the Proterozoic Eon, where fundamental questions persist about the O2 content of Earth’s atmosphere and its relationship to temporal patterns of biological innovation.The oxygenation of Earth surface environments was a protracted process that occurred over >2 billion years (Ga) (see Lyons et al., 2014

Lyons, T.W., Reinhard, C.T., Planavsky, N.J. (2014) The rise of oxygen in Earth’s early ocean and atmosphere. Nature 506, 307-315.

). Two first-order oxygen pulses have been identified from the Proterozoic geologic record. During the Great Oxidation Event (GOE) at ~2.4 Ga, pO2 was sustained above 10-5 PAL for the first time in Earth history, although transient ‘whiffs’ of O2 have been recognised from the Archaean geochemical record. During a subsequent Neoproterozoic oxygenation event (NOE) at ~635-550 Ma, pO2 began to rise to near-modern levels – a transition that continued into the Palaeozoic Era.Empirical constraints remain limited, however, on pO2 during the prolonged period in between. Constraining pO2 during the mid-Proterozoic Eon has major implications for understanding potential biogeochemical controls on the timing of animal diversification. Some argue that exceedingly low mid-Proterozoic pO2 was a direct impediment to metazoan evolution prior to the Neoproterozoic Era (Planavsky et al., 2014

Planavsky, N.J., Reinhard, C.T., Wang, X., Thomson, D., McGoldrick, P., Rainbird, R.H., Johnson, T., Fischer, W.W., Lyons, T.W. (2014) Low mid-Proterozoic atmospheric oxygen levels and the delayed rise of animals. Science 346, 635-638.

), whereas others argue that oxygen levels required by early animals were in place long before their Neoproterozoic appearance (Butterfield, 2009Butterfield, N.J. (2009) Oxygen, animals and oceanic ventilation: an alternative view. Geobiology 7, 1-7.

; Zhang et al., 2016Zhang, S., Wang, X., Wang, H., Bjerrum, C.J., Hammarlund, E.U., Mafalda Costa, M., Connelly, J.N., Zhang, B., Su, J., Canfield, D.E. (2016) Sufficient oxygen for animal respiration 1,400 million years ago. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 113, 1731-1736.

). Mid-Proterozoic Cr-isotope data have the potential to inform this debate because estimates of the pO2 threshold needed for Cr-isotope fractionation are roughly similar to experimental and theoretical estimates of the O2 requirements of early animals (0.3 to 4 % PAL) (e.g., Mills et al., 2014Mills, D.B., Ward, L.M., Jones, C., Sweeten, B., Forth, M., Treusch, A.H., Canfield, D.E. (2014) Oxygen requirements of the earliest animals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 111, 4168-4172.

).Thus far, studies have largely focused on iron-rich sedimentary rocks as an archive for ancient seawater δ53Cr values. In the presence of Fe(II), seawater Cr(VI) is reduced to Cr(III) and can be co-precipitated with Fe-(oxyhydr)oxides. Cr-reduction favours the light 52Cr isotope, so that iron-rich rocks record seawater δ53Cr values only if Cr-reduction is quantitative. Ironstone and iron formation data have thus far provided important constraints on Archaean ‘whiffs’ of oxygen and the subsequent GOE, as well as new clues about the NOE (Frei et al., 2009

Frei, R., Gaucher, C., Poulton, S.W., Canfield, D.E. (2009) Fluctuations in Precambrian atmospheric oxygenation recorded by chromium isotopes. Nature 461, 250-253.

). Sparse ironstone data from the mid-Proterozoic suggest a lack of Cr-isotope fractionation (Planavsky et al., 2014Planavsky, N.J., Reinhard, C.T., Wang, X., Thomson, D., McGoldrick, P., Rainbird, R.H., Johnson, T., Fischer, W.W., Lyons, T.W. (2014) Low mid-Proterozoic atmospheric oxygen levels and the delayed rise of animals. Science 346, 635-638.

). Iron-rich rocks are rare in mid-Proterozoic successions, however, limiting our ability to generate data for the crucial period preceding the NOE.The impetus of this study, then, is to test the reliability of Cr-isotopes in marine carbonate rocks that are ubiquitous in the mid-Proterozoic geologic record. A potential advantage of using carbonate rocks as a Cr-isotope archive is that chromate can be incorporated into the lattice of carbonate minerals with no change in oxidation state. Studies of modern invertebrate shells reveal that Cr-isotope fractionation does occur during biomineralisation, making skeletal carbonates an unreliable archive of seawater δ53Cr values (Pereira et al., 2016

Pereira, N.S., Voegelin, A.R., Paulukat, C., Sial, A.N., Ferreira, V.P., Frei, R. (2016) Chromium-isotope signatures in scleractinian corals from the Rocas Atoll, Tropical South Atlantic. Geobiology 14, 54-67.

). Mohanta et al. (2016)Mohanta, J., Holmden, C., Blanchon, P. (2016) Chromium isotope fractionation between seawater and carbonate sediment in the Caribbean Sea. Goldschmidt Abstracts, http://goldschmidt.info/2016/uploads/abstracts/finalPDFs/2121.pdf.

showed that modern bulk biogenic carbonate is as much as 0.45 ‰ lighter than seawater. Co-precipitation experiments involving chromate incorporation into calcite have shown, however, that abiogenic carbonate has the potential to record δ53Cr values of the ambient solution (Rodler et al., 2015Rodler, A., Sanchez-Pastor, N., Fernandez-Diaz, L., Frei, R. (2015) Fractionation behavior of chromium isotopes during coprecipitation with calcium carbonate: implications for their use as paleoclimatic proxy. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 164, 221-235.

). In experiments with the lowest initial Cr concentration (8.6 ppm), precipitates were <0.1 ‰ heavier than the solution, suggesting that minimal fractionation occurs during chromate incorporation into calcite at low Cr concentrations typical of seawater (0.08 to 0.5 ppm).In this study, we measured the Cr-isotopic composition of marine limestone and dolostone from four geographically distinct mid-Proterozoic successions, along with a suite of major and trace elements to constrain diagenetic pathways and the influence of detrital contamination. We focused on the interval between ~1.1 and 0.9 Ga – where sea level highstand resulted in marine carbonate deposition across multiple cratons – and a variety of depositional environments to assess the consistency and reliability of the proxy. Samples were carefully selected based on known criteria for identifying diagenetic alteration and detrital contamination, and our data are ultimately used to provide important new constraints on atmospheric pO2 during the mid-Proterozoic Eon.

top

Background and Methods

Samples were analysed from the Turukhansk Uplift, Siberia (~900-1035 Ma), the Angmaat Formation, Canada (~1092 Ma), the El Mreiti Group, Mauritania (~1107 Ma), and the Vazante Group, Brazil (~1112 Ma). Cr-isotope and Cr concentration measurements were performed on a thermal ionisation mass spectrometer. Ca, Mg, Fe, Sr, Mn, and Al concentrations were measured by ICP-OES, and Ti and Zr concentrations were measured by ICP-MS (see Supplementary Information).

top

Diagenesis

The chemical reactivity of carbonate minerals during diagenesis requires detailed understanding of potential diagenetic processes prior to selecting samples for Cr-isotope analysis. Here we employ a robust set of screening criteria for sample inclusion. Conventional light and cathodoluminescence petrography permit recognition of recrystallisation processes and secondary phases, and a combination of isotopic and elemental analyses provide evidence for fluid alteration based on the relative mobility of ions within lattice components. In short, samples containing substantial evidence for diagenetic alteration (e.g., Ostwald ripening, loss of fabric details, and secondary precipitation phases) were excluded (S-1, S-2). We then compared isotopic and trace element trends that are sensitive to fluid interaction (e.g., δ18O, [Sr], [Mn]; Banner and Hanson, 1990

Banner, J.L., Hanson, G.N. (1990) Calculation of simultaneous isotopic and trace element variations during water-rock interaction with applications to carbonate diagenesis. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 54, 3123-3137.

) to values recorded across a range of preservation states within Proterozoic carbonates (e.g., Kaufman and Knoll, 1995Kaufman, A.J., Knoll, A.H. (1995) Neoproterozoic variations in the C-isotopic composition of seawater: stratigraphic and biogeochemical implications. Precambrian Research 73, 27-49.

; Bartley et al., 2007Bartley, J.K., Kah, L.C., McWilliams, J.L., Stagner, A.F. (2007) Carbon isotope chemostratigraphy of the Middle Riphean type section (Avzyan Formation, Southern Urals, Russia): signal recovery in a fold-and-thrust belt. Chemical Geology 237, 211-232.

; Kah et al., 2012Kah, L.C., Bartley, J.K., Teal, D.A. (2012) Chemostratigraphy of the late Mesoproterozoic Atar Group, Taoudeni Basin, Mauritania: muted isotopic variability, facies correlation, and global isotopic trends. Precambrian Research 200-203, 82-103.

), conservatively excluding outliers that are depleted in 18O, substantially enriched in Mn, or depleted in Sr (Fig. S-3). We interpret our Cr-isotope data within the context of these standard criteria, acknowledging that additional work is necessary specifically to explore Cr behaviour during carbonate diagenesis. Detailed mineralogical, textural, and geochemical information can be found in the Supplementary Information.top

Detrital Chromium

Our results indicate a broad range of δ53Cr values in each succession, ranging from crustal values (near –0.12 ‰) to strongly positive values (up to +1.77 ‰). To understand this isotopic heterogeneity, we first evaluated the degree to which measured δ53Cr values reflect authigenic Cr in carbonate vs. allogenic Cr from detrital sources. As part of each dissolution for δ53Cr analysis, we measured a split for aluminium (Al) content to assess the degree to which clay – which can be a host phase for detrital Cr – was leached during dissolution. In a plot of Al concentration in the leachate vs. raw δ53Cr values (Fig. 1a), positively fractionated δ53Cr is only recorded in samples where less than ~400 ppm Al is leached. A similar trend is observed for other detrital indicators. Positively fractionated δ53Cr is only observed when leachate titanium (Ti) and zirconium (Zr) concentrations are generally less than 10 and 1 ppm, respectively (Fig. S-4), although the relationship is not well-defined for Zr. Assuming that Al is the most effective indicator of clay contamination, we compared sample Cr/Al ratios to an average shale composite (Cr = 90 ppm; Al = 8.89 wt. %; Wedepohl, 1991

Wedepohl, K.H. (1991) The composition of the upper Earth’s crust and the natural cycles of selected metals. In: Merian, E. (Ed.) Metals and their compounds in the environment: occurrence, analysis, and biological relevance. VCH, Weinheim, New York, Basel, Cambridge, 3-17.

) – which serves as a first-order proxy for clay-rich detrital sediment – to derive a rough estimate of the fraction of Cr sourced from detrital material for each sample. Similarly, positively fractionated δ53Cr is only recorded in samples where less than ~35 % of measured Cr is detritally sourced (Fig. 1b).

Figure 1 (a) Cross-plot of raw Cr-isotope values and Al concentration in the leachate. Dashed line is at 400 ppm Al. (b) Cross-plot of raw Cr-isotope values and % detrital Cr based on enrichment above average shale. Dashed line is at 35 %.

These trends represent a mixing curve where Cr in the carbonate lattice is dissolved and analysed in addition to Cr leached from clay. When detrital Cr exceeds ~35 % of total measured Cr, δ53Cr values approach average crust (–0.12 ‰) and the isotopic composition of the authigenic seawater component is unresolvable. When samples have less than ~35 % detrital Cr, we can perform a basic correction of raw δ53Cr values, assuming the detrital component has a crustal δ53Cr value. This yields a first-order estimate of the isotopic composition of the authigenic Cr component (δ53Crauth), which is thought to be derived from seawater (see Supplementary Information).

After exclusion of samples based on diagenetic and detrital contamination criteria, our dataset consisted of 62 samples that cover all four successions. These methods for assessing detrital Cr contamination represent a new set of best practices that should be applied in future Cr-isotope studies of carbonate rocks.

top

Atmospheric Oxygen

The main observation of our dataset is that all four successions record positively fractionated δ53Crauth values. The maximum isotopic difference observed by Rodler et al. (2015)

Rodler, A., Sanchez-Pastor, N., Fernandez-Diaz, L., Frei, R. (2015) Fractionation behavior of chromium isotopes during coprecipitation with calcium carbonate: implications for their use as paleoclimatic proxy. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 164, 221-235.

between synthetic calcite and ambient solution was 0.33 ‰ so that, even if some fractionation did occur during carbonate formation, the preponderance of strongly positive δ53Cr values in our dataset (n = 24 samples >0.3 ‰) indicates that mid-Proterozoic seawater was positively fractionated. Additionally, if carbonate preferentially incorporated 52Cr as observed by Mohanta et al. (2016)Mohanta, J., Holmden, C., Blanchon, P. (2016) Chromium isotope fractionation between seawater and carbonate sediment in the Caribbean Sea. Goldschmidt Abstracts, http://goldschmidt.info/2016/uploads/abstracts/finalPDFs/2121.pdf.

, then our dataset provides even stronger evidence for positively fractionated Cr in mid-Proterozoic seawater, assuming that carbonates are able to retain their original δ53Cr signature.The record of positively fractionated Cr in seawater has recently been extended back to ~3.8 Ga, which Frei et al. (2016)

Frei, R., Crowe, S.A., Bau, M., Polat, A., Fowle, D.A., Døssing, L.N. (2016) Oxidative elemental cycling under the low O2 Eoarchean atmosphere. Scientific Reports 6, 21058.

interpret as terrestrial Cr-oxidation under an otherwise anoxic Archaean atmosphere. Banded iron formations from the Archaean-Proterozoic transition record pulses of terrestrial Cr-oxidation prior to the GOE and a lack of Cr-isotope fractionation immediately following the GOE, which is interpreted as a post-GOE decline in atmospheric pO2 (Frei et al., 2009Frei, R., Gaucher, C., Poulton, S.W., Canfield, D.E. (2009) Fluctuations in Precambrian atmospheric oxygenation recorded by chromium isotopes. Nature 461, 250-253.

). Subsequent evidence for Cr-isotope fractionation was not found until ~750 Ma (Planavsky et al., 2014Planavsky, N.J., Reinhard, C.T., Wang, X., Thomson, D., McGoldrick, P., Rainbird, R.H., Johnson, T., Fischer, W.W., Lyons, T.W. (2014) Low mid-Proterozoic atmospheric oxygen levels and the delayed rise of animals. Science 346, 635-638.

), leading to the suggestion that low pO2 inhibited Cr-isotope fractionation during the mid-Proterozoic Eon. Here we extend the mid-Proterozoic record of positively fractionated Cr back to ~1.1 Ga – a revision of ~350 Ma from previous estimates (Fig. 2).

Figure 2 Compilation of all published Proterozoic Cr-isotope data including new data presented here. δ53Crauth values (after detrital correction) are presented for data from this study.

At present, there is no clear consensus on the pO2 level required for Cr-isotope fractionation during terrestrial weathering. If we take soil residence time calculations (~0.1 to 1 % PAL; Planavsky et al., 2014

Planavsky, N.J., Reinhard, C.T., Wang, X., Thomson, D., McGoldrick, P., Rainbird, R.H., Johnson, T., Fischer, W.W., Lyons, T.W. (2014) Low mid-Proterozoic atmospheric oxygen levels and the delayed rise of animals. Science 346, 635-638.

) as our best estimate, we conclude that pO2 at least transiently exceeded ~0.1 to 1 % PAL during the mid-Proterozoic Eon. These data are consistent with a broad range of proxies that suggest increasing biospheric oxygen in the Mesoproterozoic Era (Kah et al., 2001Kah, L.C., Lyons, T.W., Chesley, J.T. (2001) Geochemistry of a 1.2 Ga carbonate-evaporite succession, northern Baffin and Bylot Islands: implications for Mesoproterozoic marine evolution. Precambrian Research 111, 203-234.

; Johnston et al., 2005Johnston, D.T., Wing, B.A., Farquhar, J., Kaufman, A.J., Strauss, H., Lyons, T.W., Kah, L.C., Canfield, D.E. (2005) Active microbial sulfur disproportionation in the Mesoproterozoic. Science 310, 1477-1479.

; Parnell et al., 2010Parnell, J., Boyce, A.J., Mark, D., Bowden, S., Spinks, S. (2010) Early oxygenation of the terrestrial environment during the Mesoproterozoic. Nature 468, 290-293.

; Zhang et al., 2016Zhang, S., Wang, X., Wang, H., Bjerrum, C.J., Hammarlund, E.U., Mafalda Costa, M., Connelly, J.N., Zhang, B., Su, J., Canfield, D.E. (2016) Sufficient oxygen for animal respiration 1,400 million years ago. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 113, 1731-1736.

). Data are potentially inconsistent, however, with recent estimates of maximum pO2 between 0.1 and 1 % PAL during the mid-Proterozoic Eon, including Cr-isotope data from sparse mid-Proterozoic iron oolites (Planavsky et al., 2014Planavsky, N.J., Reinhard, C.T., Wang, X., Thomson, D., McGoldrick, P., Rainbird, R.H., Johnson, T., Fischer, W.W., Lyons, T.W. (2014) Low mid-Proterozoic atmospheric oxygen levels and the delayed rise of animals. Science 346, 635-638.

; Liu et al., 2016Liu, X.M., Kah, L.C., Knoll, A.H., Cui, H., Kaufman, A.J., Shahar, A., Hazen, R.M. (2016) Tracing Earth’s O2 evolution using Zn/Fe ratios in marine carbonates. Geochemical Perspectives Letters 2, 24-34.

).Potential conflict between our data and other proxies could be related to uncertainty regarding the pO2 threshold required for Cr-isotope fractionation. If we take 0.03 % PAL as the required threshold, for example, our data become compatible with the pO2 estimate of Liu et al. (2016)

Liu, X.M., Kah, L.C., Knoll, A.H., Cui, H., Kaufman, A.J., Shahar, A., Hazen, R.M. (2016) Tracing Earth’s O2 evolution using Zn/Fe ratios in marine carbonates. Geochemical Perspectives Letters 2, 24-34.

based on carbonate Zn/Fe systematics. Regardless of the threshold value, however, our data remain inconsistent with Cr-isotope data from mid-Proterozoic iron oolites. This discrepancy cannot be explained by Cr-isotope fractionation during carbonate formation, particularly if carbonates preferentially incorporate 52Cr (Mohanta et al., 2016Mohanta, J., Holmden, C., Blanchon, P. (2016) Chromium isotope fractionation between seawater and carbonate sediment in the Caribbean Sea. Goldschmidt Abstracts, http://goldschmidt.info/2016/uploads/abstracts/finalPDFs/2121.pdf.

), which would only amplify evidence for positively fractionated Cr in mid-Proterozoic seawater. We have also robustly screened our samples for diagenesis using standard petrographic and geochemical criteria, although diagenetic effects cannot be completely discounted given uncertainty regarding Cr behaviour during carbonate diagenesis. To this end, we compared δ53Cr to δ18O as a diagenetic indicator, and found that the lowest δ18O values in our dataset – normally thought to reflect diagenetic alteration – are associated with unfractionated δ53Cr values (Fig. S-5). This could indicate that, at least in our dataset, diagenesis is more likely to give a false negative than a false positive result. Another possibility is that ironstone data do not record seawater δ53Cr because of partial Cr-reduction during precipitation of shallow water iron oolites, which may have occurred under fluctuating redox conditions. As articulated by Planavsky et al. (2014)Planavsky, N.J., Reinhard, C.T., Wang, X., Thomson, D., McGoldrick, P., Rainbird, R.H., Johnson, T., Fischer, W.W., Lyons, T.W. (2014) Low mid-Proterozoic atmospheric oxygen levels and the delayed rise of animals. Science 346, 635-638.

, however, this would be expected to generate a range of δ53Cr values – not the persistently unfractionated values that were measured.Another alternative is that mid-Proterozoic pO2 was variable around the threshold required for Cr-isotope fractionation. There is evidence for this in our dataset – the persistence of unfractionated δ53Cr values that are not related to detrital contamination (Fig. 1) could be related to transient periods of pO2 below threshold values. Indeed the only measured iron oolites that temporally overlap with samples from this study are limited samples from the ~0.9 Ga Aok Formation (Canada), implying that the coarse temporal resolution of current data may be insufficient to track short-term variability in pO2. Taken together with the full range of published proxy data, we conclude that mid-Proterozoic pO2 was likely more dynamic than previously envisaged.

top

Biological Implications

Implications of our data on biospheric evolution are similarly tied to uncertainty regarding the pO2 threshold needed for Cr-isotope fractionation. Tank experiments have shown that sponges can survive when pO2 is as low as 0.5 to 4 % PAL, leading Mills et al. (2014)

Mills, D.B., Ward, L.M., Jones, C., Sweeten, B., Forth, M., Treusch, A.H., Canfield, D.E. (2014) Oxygen requirements of the earliest animals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 111, 4168-4172.

to conclude that this level was likely sufficient for the origin of animals. Based on theoretical early annelid body plans, a small worm with a circulatory system could likely survive at pO2 as low as 0.14 % PAL (Sperling et al., 2013aSperling, E.A., Halverson, G.P., Knoll, A.H., Macdonald, F.A., Johnston, D.T. (2013a) A basin redox transect at the dawn of animal life. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 371-372, 143-155.

). Studies from modern oxygen minimum zones confirm these estimates and suggest that the bilaterian body plan would only be inhibited if pO2 were below 0.4 % PAL. If we take 0.1 to 1 % PAL as the threshold required for Cr-isotope fractionation, then our data suggest that pO2 levels sufficient for the origin of animals were at least transiently in place by ~1.1 Ga – some 300 Ma before the origin of sponges based on molecular clock estimates (Erwin et al., 2011Erwin, D.H., Laflamme, M., Tweedt, S.M., Sperling, E.A., Pisani, D., Peterson, K.J. (2011) The Cambrian conundrum: early divergence and later ecological success in the early history of animals. Science 334, 1091-1097.

) and >450 Ma before the first appearance of animals in the fossil record. By contrast, if we take a lower threshold value of 0.03 % PAL, then our data have less direct implications for biology. Ecological considerations are also important and modern oxygen minimum zones suggest that there is a clear linkage between oxygen availability, animal size, and the relative proportion of carnivorous taxa (Sperling et al., 2013bSperling, E.A., Frieder, C.A., Raman, A.V., Girguis, P.R., Levin, L.A., Knoll, A.H. (2013b) Oxygen, ecology, and the Cambrian radiation of animals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 110, 13446-13451.

). Based on these considerations it seems that, although the oxygen requirements of small, simple animals were likely met by ~1.1 Ga, low atmospheric pO2 may still have inhibited the development of larger, more energetic animals that have greater preservation potential in the fossil record.top

Conclusions

This study demonstrates the viability of the Cr-isotope palaeo-redox proxy as it is applied to ancient carbonate rocks. After screening for detrital contamination – and assuming that our least-altered samples are able to retain original δ53Cr values – Cr-isotope data can be interpreted in the context of ancient atmospheric pO2. Results from four carbonate successions extend the mid-Proterozoic record of positively fractionated Cr back to ~1.1 Ga – a revision of ~350 Ma from previous estimates. If we take 0.1 to 1 % PAL as the pO2 threshold needed for Cr-isotope fractionation, then our data suggest that the oxygen requirements of small, simple animals were at least transiently met well prior to their Neoproterozoic appearance, although uncertainty regarding this pO2 threshold precludes definitive biological interpretation. Ultimately, the development of novel carbonate-based redox proxies has the potential to greatly enhance the temporal resolution of palaeo-redox data for the Proterozoic Eon.

top

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the Danish Natural Science Research Council (FNU) to R.F. and the Carlsberg Foundation to G.J.G. and R.F. A.H.K. thanks the NASA Astrobiology Institute and G.J.G. thanks Ariel Anbar and the NASA Postdoctoral Program. We are indebted to Toni Larsen for help in ion chromatographic separation of Cr, Toby Leeper for mass spectrometry support, Jørgen Kystol for running the ICP-MS, and Andrea Voegelin for major contributions to Cr-isotope analytical and data interpretation techniques. We also thank Clemens V. Ullmann for ICP-OES expertise and insightful comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript.

Editor: Eric H. Oelkers

top

References

Banner, J.L., Hanson, G.N. (1990) Calculation of simultaneous isotopic and trace element variations during water-rock interaction with applications to carbonate diagenesis. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 54, 3123-3137.

Show in context

Show in context We then compared isotopic and trace element trends that are sensitive to fluid interaction (e.g., δ18O, [Sr], [Mn]; Banner and Hanson, 1990) to values recorded across a range of preservation states within Proterozoic carbonates (e.g., Kaufman and Knoll, 1995; Bartley et al., 2007; Kah et al., 2012), conservatively excluding outliers that are depleted in 18O, substantially enriched in Mn, or depleted in Sr (Fig. S-3).

View in article

Bartley, J.K., Kah, L.C., McWilliams, J.L., Stagner, A.F. (2007) Carbon isotope chemostratigraphy of the Middle Riphean type section (Avzyan Formation, Southern Urals, Russia): signal recovery in a fold-and-thrust belt. Chemical Geology 237, 211-232.

Show in context

Show in context We then compared isotopic and trace element trends that are sensitive to fluid interaction (e.g., δ18O, [Sr], [Mn]; Banner and Hanson, 1990) to values recorded across a range of preservation states within Proterozoic carbonates (e.g., Kaufman and Knoll, 1995; Bartley et al., 2007; Kah et al., 2012), conservatively excluding outliers that are depleted in 18O, substantially enriched in Mn, or depleted in Sr (Fig. S-3).

View in article

Bonnand, P., James, R.H., Parkinson, I.J., Connelly, D.P., Fairchild, I.J. (2013) The chromium isotopic composition of seawater and marine carbonates. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 382, 10-20.

Show in context

Show in context Cr(VI) (dominantly as chromate; CrO4-) is then carried to the oceans via rivers, thus imparting a positively fractionated δ53Cr signal on modern seawater (+0.41 to +1.55 ‰ compared to crustal values of –0.123 ± 0.102 ‰) (Schoenberg et al., 2008; Bonnand et al., 2013; Scheiderich et al., 2015).

View in article

Butterfield, N.J. (2009) Oxygen, animals and oceanic ventilation: an alternative view. Geobiology 7, 1-7.

Show in context

Show in context Some argue that exceedingly low mid-Proterozoic pO2 was a direct impediment to metazoan evolution prior to the Neoproterozoic Era (Planavsky et al., 2014), whereas others argue that oxygen levels required by early animals were in place long before their Neoproterozoic appearance (Butterfield, 2009; Zhang et al., 2016).

View in article

Crowe, S.A., Døssing, L.N., Beukes, N.J., Bau, M., Kruger, S.J., Frei, R., Canfield, D.E. (2013) Atmospheric oxygenation three billion years ago. Nature 501, 535-538.

Show in context

Show in context Kinetic considerations dictate, however, that 0.1 to 1 % PAL is necessary to oxidise Cr(III) within typical soil residence times (Planavsky et al., 2014) and between 0.03 and 0.3 % PAL is necessary to export Cr without re-reduction by Fe(II) (Crowe et al., 2013).

View in article

Erwin, D.H., Laflamme, M., Tweedt, S.M., Sperling, E.A., Pisani, D., Peterson, K.J. (2011) The Cambrian conundrum: early divergence and later ecological success in the early history of animals. Science 334, 1091-1097.

Show in context

Show in context If we take 0.1 to 1 % PAL as the threshold required for Cr-isotope fractionation, then our data suggest that pO2 levels sufficient for the origin of animals were at least transiently in place by ~1.1 Ga - some 300 Ma before the origin of sponges based on molecular clock estimates (Erwin et al., 2011) and >450 Ma before the first appearance of animals in the fossil record.

View in article

Frei, R., Gaucher, C., Poulton, S.W., Canfield, D.E. (2009) Fluctuations in Precambrian atmospheric oxygenation recorded by chromium isotopes. Nature 461, 250-253.

Show in context

Show in context Ironstone and iron formation data have thus far provided important constraints on Archaean ‘whiffs’ of oxygen and the subsequent GOE, as well as new clues about the NOE (Frei et al., 2009).

View in article

Banded iron formations from the Archaean-Proterozoic transition record pulses of terrestrial Cr-oxidation prior to the GOE and a lack of Cr-isotope fractionation immediately following the GOE, which is interpreted as a post-GOE decline in atmospheric pO2 (Frei et al., 2009).

View in article

Frei, R., Crowe, S.A., Bau, M., Polat, A., Fowle, D.A., Døssing, L.N. (2016) Oxidative elemental cycling under the low O2 Eoarchean atmosphere. Scientific Reports 6, 21058.

Show in context

Show in context Frei et al. (2016) suggested that Cr-oxidation by Mn-oxides is thermodynamically possible at pO2 as low as 10-5 of the present atmospheric level (PAL).

View in article

The record of positively fractionated Cr in seawater has recently been extended back to ~3.8 Ga, which Frei et al. (2016) interpret as terrestrial Cr-oxidation under an otherwise anoxic Archaean atmosphere.

View in article

Johnston, D.T., Wing, B.A., Farquhar, J., Kaufman, A.J., Strauss, H., Lyons, T.W., Kah, L.C., Canfield, D.E. (2005) Active microbial sulfur disproportionation in the Mesoproterozoic. Science 310, 1477-1479.

Show in context

Show in context These data are consistent with a broad range of proxies that suggest increasing biospheric oxygen in the Mesoproterozoic Era (Kah et al., 2001; Johnston et al., 2005; Parnell et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2016).

View in article

Kah, L.C., Lyons, T.W., Chesley, J.T. (2001) Geochemistry of a 1.2 Ga carbonate-evaporite succession, northern Baffin and Bylot Islands: implications for Mesoproterozoic marine evolution. Precambrian Research 111, 203-234.

Show in context

Show in context These data are consistent with a broad range of proxies that suggest increasing biospheric oxygen in the Mesoproterozoic Era (Kah et al., 2001; Johnston et al., 2005; Parnell et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2016).

View in article

Kah, L.C., Bartley, J.K., Teal, D.A. (2012) Chemostratigraphy of the late Mesoproterozoic Atar Group, Taoudeni Basin, Mauritania: muted isotopic variability, facies correlation, and global isotopic trends. Precambrian Research 200-203, 82-103.

Show in context

Show in context We then compared isotopic and trace element trends that are sensitive to fluid interaction (e.g., δ18O, [Sr], [Mn]; Banner and Hanson, 1990) to values recorded across a range of preservation states within Proterozoic carbonates (e.g., Kaufman and Knoll, 1995; Bartley et al., 2007; Kah et al., 2012), conservatively excluding outliers that are depleted in 18O, substantially enriched in Mn, or depleted in Sr (Fig. S-3).

View in article

Kaufman, A.J., Knoll, A.H. (1995) Neoproterozoic variations in the C-isotopic composition of seawater: stratigraphic and biogeochemical implications. Precambrian Research 73, 27-49.

Show in context

Show in context We then compared isotopic and trace element trends that are sensitive to fluid interaction (e.g., δ18O, [Sr], [Mn]; Banner and Hanson, 1990) to values recorded across a range of preservation states within Proterozoic carbonates (e.g., Kaufman and Knoll, 1995; Bartley et al., 2007; Kah et al., 2012), conservatively excluding outliers that are depleted in 18O, substantially enriched in Mn, or depleted in Sr (Fig. S-3).

View in article

Liu, X.M., Kah, L.C., Knoll, A.H., Cui, H., Kaufman, A.J., Shahar, A., Hazen, R.M. (2016) Tracing Earth’s O2 evolution using Zn/Fe ratios in marine carbonates. Geochemical Perspectives Letters 2, 24-34.

Show in context

Show in context Data are potentially inconsistent, however, with recent estimates of maximum pO2 between 0.1 and 1 % PAL during the mid-Proterozoic Eon, including Cr-isotope data from sparse mid-Proterozoic iron oolites (Planavsky et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2016).

View in article

If we take 0.03 % PAL as the required threshold, for example, our data become compatible with the pO2 estimate of Liu et al. (2016) based on carbonate Zn/Fe systematics.

View in article

Lyons, T.W., Reinhard, C.T., Planavsky, N.J. (2014) The rise of oxygen in Earth’s early ocean and atmosphere. Nature 506, 307-315.

Show in context

Show in context The oxygenation of Earth surface environments was a protracted process that occurred over >2 billion years (Ga) (see Lyons et al., 2014).

View in article

Mills, D.B., Ward, L.M., Jones, C., Sweeten, B., Forth, M., Treusch, A.H., Canfield, D.E. (2014) Oxygen requirements of the earliest animals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 111, 4168-4172.

Show in context

Show in context Mid-Proterozoic Cr-isotope data have the potential to inform this debate because estimates of the pO2 threshold needed for Cr-isotope fractionation are roughly similar to experimental and theoretical estimates of the O2 requirements of early animals (0.3 to 4 % PAL) (e.g., Mills et al., 2014).

View in article

Tank experiments have shown that sponges can survive when pO2 is as low as 0.5 to 4 % PAL, leading Mills et al. (2014) to conclude that this level was likely sufficient for the origin of animals.

View in article

Mohanta, J., Holmden, C., Blanchon, P. (2016) Chromium isotope fractionation between seawater and carbonate sediment in the Caribbean Sea. Goldschmidt Abstracts, http://goldschmidt.info/2016/uploads/abstracts/finalPDFs/2121.pdf.

Show in context

Show in context Mohanta et al. (2016) showed that modern bulk biogenic carbonate is as much as 0.45 ‰ lighter than seawater.

View in article

Additionally, if carbonate preferentially incorporated 52Cr as observed by Mohanta et al. (2016), then our dataset provides even stronger evidence for positively fractionated Cr in mid-Proterozoic seawater, assuming that carbonates are able to retain their original δ53Cr signature.

View in article

This discrepancy cannot be explained by Cr-isotope fractionation during carbonate formation, particularly if carbonates preferentially incorporate 52Cr (Mohanta et al., 2016), which would only amplify evidence for positively fractionated Cr in mid-Proterozoic seawater.

View in article

Parnell, J., Boyce, A.J., Mark, D., Bowden, S., Spinks, S. (2010) Early oxygenation of the terrestrial environment during the Mesoproterozoic. Nature 468, 290-293.

Show in context

Show in context These data are consistent with a broad range of proxies that suggest increasing biospheric oxygen in the Mesoproterozoic Era (Kah et al., 2001; Johnston et al., 2005; Parnell et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2016).

View in article

Pereira, N.S., Voegelin, A.R., Paulukat, C., Sial, A.N., Ferreira, V.P., Frei, R. (2016) Chromium-isotope signatures in scleractinian corals from the Rocas Atoll, Tropical South Atlantic. Geobiology 14, 54-67.

Show in context

Show in context Studies of modern invertebrate shells reveal that Cr-isotope fractionation does occur during biomineralisation, making skeletal carbonates an unreliable archive of seawater δ53Cr values (Pereira et al., 2016).

View in article

Planavsky, N.J., Reinhard, C.T., Wang, X., Thomson, D., McGoldrick, P., Rainbird, R.H., Johnson, T., Fischer, W.W., Lyons, T.W. (2014) Low mid-Proterozoic atmospheric oxygen levels and the delayed rise of animals. Science 346, 635-638.

Show in context

Show in context Rodler, A., Sanchez-Pastor, N., Fernandez-Diaz, L., Frei, R. (2015) Fractionation behavior of chromium isotopes during coprecipitation with calcium carbonate: implications for their use as paleoclimatic proxy. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 164, 221-235.

Show in context

Show in context Co-precipitation experiments involving chromate incorporation into calcite have shown, however, that abiogenic carbonate has the potential to record δ53Cr values of the ambient solution (Rodler et al., 2015).

View in article

The maximum isotopic difference observed by Rodler et al. (2015) between synthetic calcite and ambient solution was 0.33 ‰ so that, even if some fractionation did occur during carbonate formation, the preponderance of strongly positive δ53Cr values in our dataset (n = 24 samples >0.3 ‰) indicates that mid-Proterozoic seawater was positively fractionated.

View in article

Scheiderich, K., Amini, M., Holmden, C., Francois, R. (2015) Global variability of chromium isotopes in seawater demonstrated by Pacific, Atlantic, and Arctic Ocean samples. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 423, 87-97.

Show in context

Show in context Cr(VI) (dominantly as chromate; CrO4-) is then carried to the oceans via rivers, thus imparting a positively fractionated δ53Cr signal on modern seawater (+0.41 to +1.55 ‰ compared to crustal values of –0.123 ± 0.102 ‰) (Schoenberg et al., 2008; Bonnand et al., 2013; Scheiderich et al., 2015).

View in article

Schoenberg, S., Zink, M., Staubwasser, M., von Blanckenburg, F. (2008) The stable Cr isotope inventory of solid Earth reservoirs determine by double spike MC-ICP-MS. Chemical Geology 249, 294-306.

Show in context

Show in context Cr(VI) (dominantly as chromate; CrO4-) is then carried to the oceans via rivers, thus imparting a positively fractionated δ53Cr signal on modern seawater (+0.41 to +1.55 ‰ compared to crustal values of –0.123 ± 0.102 ‰) (Schoenberg et al., 2008; Bonnand et al., 2013; Scheiderich et al., 2015).

View in article

Sperling, E.A., Halverson, G.P., Knoll, A.H., Macdonald, F.A., Johnston, D.T. (2013a) A basin redox transect at the dawn of animal life. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 371-372, 143-155.

Show in context

Show in context Based on theoretical early annelid body plans, a small worm with a circulatory system could likely survive at pO2 as low as 0.14 % PAL (Sperling et al., 2013a).

View in article

Sperling, E.A., Frieder, C.A., Raman, A.V., Girguis, P.R., Levin, L.A., Knoll, A.H. (2013b) Oxygen, ecology, and the Cambrian radiation of animals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 110, 13446-13451.

Show in context

Show in context Ecological considerations are also important and modern oxygen minimum zones suggest that there is a clear linkage between oxygen availability, animal size, and the relative proportion of carnivorous taxa (Sperling et al., 2013b).

View in article

Wedepohl, K.H. (1991) The composition of the upper Earth’s crust and the natural cycles of selected metals. In: Merian, E. (Ed.) Metals and their compounds in the environment: occurrence, analysis, and biological relevance. VCH, Weinheim, New York, Basel, Cambridge, 3-17.

Show in context

Show in context Assuming that Al is the most effective indicator of clay contamination, we compared sample Cr/Al ratios to an average shale composite (Cr = 90 ppm; Al = 8.89 wt. %; Wedepohl, 1991) - which serves as a first-order proxy for clay-rich detrital sediment - to derive a rough estimate of the fraction of Cr sourced from detrital material for each sample.

View in article

Zhang, S., Wang, X., Wang, H., Bjerrum, C.J., Hammarlund, E.U., Mafalda Costa, M., Connelly, J.N., Zhang, B., Su, J., Canfield, D.E. (2016) Sufficient oxygen for animal respiration 1,400 million years ago. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 113, 1731-1736.

Show in context

Show in context Some argue that exceedingly low mid-Proterozoic pO2 was a direct impediment to metazoan evolution prior to the Neoproterozoic Era (Planavsky et al., 2014), whereas others argue that oxygen levels required by early animals were in place long before their Neoproterozoic appearance (Butterfield, 2009; Zhang et al., 2016).

View in article

These data are consistent with a broad range of proxies that suggest increasing biospheric oxygen in the Mesoproterozoic Era (Kah et al., 2001; Johnston et al., 2005; Parnell et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2016).

View in article

top

Supplementary Information

Geologic Background

Turukhansk Uplift, Siberia

The Turukhansk Uplift succession – deposited along the northwestern edge of the Siberian craton – is comprised of thick (>4 km) unmetamorphosed carbonate and siliciclastic strata that are exposed in three thrust-bounded blocks (Petrov and Semikhatov, 1997

Petrov, P.Y., Semikhatov, M.A. (1997) Structure and environmental conditions of a transgressive Upper Riphean complex: Miroyedikha Formation of the Turukhansk Uplift, Siberia. Lithology and Mineral Resources 32, 11-29.

, 1998Petrov, P.Y., Semikhatov, M.A. (1998) The upper Riphean stromatolitic reefal complex; Burovaya Formation of the Turukhansk region, Siberia. Lithology and Mineral Resources 33, 539-560.

; Sergeev, 2001Sergeev, V.N. (2001) Paleobiology of the Neoproterozoic (Upper Riphean) Shorikha and Burovaya silicified microbiotas, Turukhansk Uplift, Siberia. Journal of Paleontology 75, 427-448.

). Late Mesoproterozoic rocks are separated into two distinct intervals by a regional erosional surface. Deposition in the lower interval began with the Bezymyannyi Formation, which is an open marine siliciclastic-dominated unit that accumulated near storm wave base (Petrov, 1993aPetrov, P.Y. (1993a) Depositional environments of the lower formations of the Riphean sequence, northern part of the Turukhansk Uplift, Siberia. Stratigraphy and Geological Correlation 1, 181-191.

; Veis and Petrov, 1994Veis, A.F., Petrov, P.Y. (1994) The main peculiarities of the environmental distribution of microfossils in the Riphean basins of Siberia. Stratigrarphy and Geological Correlation 2, 97-129.

). The conformably overlying carbonate-dominated Linok Formation also accumulated near storm wave base, but palaeoenvironments shoal near the top of the unit (Petrov, 1993aPetrov, P.Y. (1993a) Depositional environments of the lower formations of the Riphean sequence, northern part of the Turukhansk Uplift, Siberia. Stratigraphy and Geological Correlation 1, 181-191.

,bPetrov, P.Y. (1993b) Structure and sedimentation environments of the Riphean Bezymyannyi Formation in the Turukhansk Uplift, Siberia. Stratigraphy and Geological Correlation 1, 490-502.

) leading into intertidal to subtidal limestone and dolostone of the Sukhaya Tunguska Formation (Petrov et al., 1995Petrov, P.Y., Semikhatov, M.A., Sergeev, V.N. (1995) Development of the Riphean carbonate platform and distribution of silicified microfossils: the Sukhaya Tunguska Formation, Turukhansk Uplift, Siberia. Stratigraphy and Geological Correlation 3, 602-620.

; Sergeev et al., 1997Sergeev, V.N., Knoll, A.H., Petrov, P.Y. (1997) Paleobiology of the Mesoproterozoic-Neoproterozoic transition: the Sukhaya Tunguska Formation, Turukhansk Uplift, Siberia. Precambrian Research 85, 201-239.

). Pb-Pb geochronology on the Sukhaya Tunguska Formation yields an age of 1035 ± 60 Ma (Ovchinnikova et al., 1995Ovchinnikova, G.V., Gorokhov, I.M., Belyatskii, B.V. (1995) U-Pb systematics of Pre-Cambrian carbonates: the Riphean Sukhaya Tunguska Formation in the Turukhansk Uplift, Siberia. Lithology and Mineral Resources 30, 525–536.

), which is consistent with correlations to better-dated successions elsewhere in Siberia and muted carbon isotope variability (Bartley et al., 2001Bartley, J.K., Semikhatov, M.A., Kaufman, A.J., Knoll, A.H., Pope, M.C., Jacobsen, S.B. (2001) Global events across the Mesoproterozoic-Neoproterozoic boundary: C and Sr isotopic evidence from Siberia. Precambrian Research 111, 165-202.

) that is characteristic of global carbon isotope trends in the late Mesoproterozoic Era (Kah et al., 1999Kah, L.C., Sherman, A.B., Narbonne, G.M., Kaufman, A.J., Knoll, A.H. (1999) d13C stratigraphy of the Proterozoic Bylot Supergroup, northern Baffin Island: implications for regional lithostratigraphic correlations. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 36, 313-332.

, 2012Kah, L.C., Bartley, J.K., Teal, D.A. (2012) Chemostratigraphy of the late Mesoproterozoic Atar Group, Taoudeni Basin, Mauritania: muted isotopic variability, facies correlation, and global isotopic trends. Precambrian Research 200-203, 82-103.

; Gilleaudeau and Kah, 2013aGilleaudeau, G.J., Kah, L.C. (2013a) Carbon isotope records in a Mesoproterozoic epicratonic sea: carbon cycling in a low-oxygen world. Precambrian Research 228, 85-101.

). An erosional disconformity of unknown duration sits atop the Sukhaya Tunguska Formation, above which the Derevnya Formation consists of stromatolitic (Jacutophyton) dolostone and shale that accumulated in an open shelf setting. Conformably overlying the Derevnya Formation is the Burovaya Formation, which accumulated along a carbonate ramp associated with stromatolitic bioherms (Petrov and Semikhatov, 1998Petrov, P.Y., Semikhatov, M.A. (1998) The upper Riphean stromatolitic reefal complex; Burovaya Formation of the Turukhansk region, Siberia. Lithology and Mineral Resources 33, 539-560.

). Carbonate of the Burovaya Formation is disconformably overlain by peritidal to shallow marine dolostone of the Shorikha Formation (Sergeev et al., 1997Sergeev, V.N., Knoll, A.H., Petrov, P.Y. (1997) Paleobiology of the Mesoproterozoic-Neoproterozoic transition: the Sukhaya Tunguska Formation, Turukhansk Uplift, Siberia. Precambrian Research 85, 201-239.

) followed by mixed siliciclastic-carbonate deeper shelf strata of the Miroyedikha Formation (Petrov and Semikhatov, 1997Petrov, P.Y., Semikhatov, M.A. (1997) Structure and environmental conditions of a transgressive Upper Riphean complex: Miroyedikha Formation of the Turukhansk Uplift, Siberia. Lithology and Mineral Resources 32, 11-29.

). Lastly, the entire succession is overlain by the dolomitic Turukhansk Formation that accumulated in shelf settings primarily between fair weather and storm wave base (Petrov and Semikhatov, 1997Petrov, P.Y., Semikhatov, M.A. (1997) Structure and environmental conditions of a transgressive Upper Riphean complex: Miroyedikha Formation of the Turukhansk Uplift, Siberia. Lithology and Mineral Resources 32, 11-29.

). Age constraints are lacking on the units above the disconformity, although they are generally assigned to the early Neoproterozoic (~900 Ma) (Sergeev et al., 1997Sergeev, V.N., Knoll, A.H., Petrov, P.Y. (1997) Paleobiology of the Mesoproterozoic-Neoproterozoic transition: the Sukhaya Tunguska Formation, Turukhansk Uplift, Siberia. Precambrian Research 85, 201-239.

; Sergeev, 2001Sergeev, V.N. (2001) Paleobiology of the Neoproterozoic (Upper Riphean) Shorikha and Burovaya silicified microbiotas, Turukhansk Uplift, Siberia. Journal of Paleontology 75, 427-448.

). Turukhansk Uplift strata have been gently tilted (15-30°) by regional structural deformation (Bartley et al., 2001Bartley, J.K., Semikhatov, M.A., Kaufman, A.J., Knoll, A.H., Pope, M.C., Jacobsen, S.B. (2001) Global events across the Mesoproterozoic-Neoproterozoic boundary: C and Sr isotopic evidence from Siberia. Precambrian Research 111, 165-202.

), but have not been subjected to regional or contact metamorphism. Outcrop samples were collected during a joint US-Russian field expedition in 1995 (near the confluence of the Yenisei and Nizhnyaya Tunguska Rivers; ~65.8° N, 87.9° E) and samples were accessed from the archives of the Botanical Museum at Harvard University.Angmaat Formation, Canada

The Bylot Supergroup is a thick (~6 km) succession of late Mesoproterozoic to early Neoproterozoic strata exposed within the fault-bounded Borden Basin on northern Baffin and Bylot islands, Nunavut, arctic Canada (Kah et al., 1999

Kah, L.C., Sherman, A.B., Narbonne, G.M., Kaufman, A.J., Knoll, A.H. (1999) d13C stratigraphy of the Proterozoic Bylot Supergroup, northern Baffin Island: implications for regional lithostratigraphic correlations. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 36, 313-332.

). Strata are divided into three unconformity-bounded sequences, and samples from this study are exclusively from the Angmaat Formation (formerly the Society Cliffs Formation), which lies at the top of the lowermost of these sequences. The dominantly dolomitic Angmaat Formation lies conformably above mixed carbonate-siliciclastic strata of the Arctic Bay and Nanisivik formations (among others; Turner and Kamber, 2012Turner, E.C., Kamber, B.S. (2012) Arctic Bay Formation, Borden Basin, Nunavut (Canada): Basin evolution, black shale, and dissolved metal systematics in the Mesoproterozoic ocean. Precambrian Research 208-211, 1-18.

) and is, in turn, unconformably overlain by the carbonate-dominated Victor Bay Formation. Differential subsidence and graben development controlled lateral facies distribution during deposition of the Angmaat Formation (Turner and Kamber, 2012Turner, E.C., Kamber, B.S. (2012) Arctic Bay Formation, Borden Basin, Nunavut (Canada): Basin evolution, black shale, and dissolved metal systematics in the Mesoproterozoic ocean. Precambrian Research 208-211, 1-18.

). Palaeoenvironments range from strongly evaporative, supratidal settings (recorded by direct carbonate precipitates, gypsum, and red beds in the Tay Sound outcrop section; Kah et al., 1999Kah, L.C., Sherman, A.B., Narbonne, G.M., Kaufman, A.J., Knoll, A.H. (1999) d13C stratigraphy of the Proterozoic Bylot Supergroup, northern Baffin Island: implications for regional lithostratigraphic correlations. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 36, 313-332.

) to subtidal settings dominated by microbial mats and ooid shoals (Milne Inlet section). The age of the Angmaat Formation is constrained by a 1199 ± 24 Ma Pb-Pb age on carbonate in the formation (Kah et al., 2001Kah, L.C., Lyons, T.W., Chesley, J.T. (2001) Geochemistry of a 1.2 Ga carbonate-evaporite succession, northern Baffin and Bylot Islands: implications for Mesoproterozoic marine evolution. Precambrian Research 111, 203-234.

), as well as a 1270 ± 4 Ma U-Pb age on subjacent volcanic rocks (Heaman et al., 1992Heaman, L.M., LeCheminant, A.N., Rainbird, R.H. (1992) Nature and timing of Franklin igneous events, Canada: implications for a late Proterozoic mantle plume and the break-up of Laurentia. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 109, 117-131.

) and a U-Th-Pb whole rock age of 1092 ± 59 Ma on shale of the Arctic Bay Formation (Turner and Kamber, 2012Turner, E.C., Kamber, B.S. (2012) Arctic Bay Formation, Borden Basin, Nunavut (Canada): Basin evolution, black shale, and dissolved metal systematics in the Mesoproterozoic ocean. Precambrian Research 208-211, 1-18.

). A late Mesoproterozoic age for the Angmaat Formation is also verified by chemostratigraphic correlation with late Mesoproterozoic strata from the Taoudeni Basin, Mauritania (Kah et al., 2012Kah, L.C., Bartley, J.K., Teal, D.A. (2012) Chemostratigraphy of the late Mesoproterozoic Atar Group, Taoudeni Basin, Mauritania: muted isotopic variability, facies correlation, and global isotopic trends. Precambrian Research 200-203, 82-103.

). Strata have not experienced regional metamorphism, and contact metamorphism occurred only in close proximity to the Neoproterozoic Franklin swarm of mafic dykes (Turner and Kamber, 2012Turner, E.C., Kamber, B.S. (2012) Arctic Bay Formation, Borden Basin, Nunavut (Canada): Basin evolution, black shale, and dissolved metal systematics in the Mesoproterozoic ocean. Precambrian Research 208-211, 1-18.

), which have not influenced the sections examined in this study. Outcrop samples were collected during a series of field expeditions in the mid-1990’s in northernmost Baffin Island, Canada (~72.2° N, 79.5° E for the White Bay outcrop section) and samples were accessed from the archives of the Botanical Museum at Harvard University.El Mreiti Group, Mauritania

The El Mreiti Group – deposited in the north-central Taoudeni Basin (West African craton) – is comprised of >350 metres of carbonate and siliciclastic strata that were deposited in the interior of a broad epeiric sea (Kah et al., 2012

Kah, L.C., Bartley, J.K., Teal, D.A. (2012) Chemostratigraphy of the late Mesoproterozoic Atar Group, Taoudeni Basin, Mauritania: muted isotopic variability, facies correlation, and global isotopic trends. Precambrian Research 200-203, 82-103.

; Gilleaudeau and Kah, 2013aGilleaudeau, G.J., Kah, L.C. (2013a) Carbon isotope records in a Mesoproterozoic epicratonic sea: carbon cycling in a low-oxygen world. Precambrian Research 228, 85-101.

,bGilleaudeau, G.J., Kah, L.C. (2013b) Oceanic molybdenum drawdown by epeiric sea expansion in the Mesoproterozoic. Chemical Geology 356, 21-37.

, 2015Gilleaudeau, G.J., Kah, L.C. (2015) Heterogeneous redox conditions and a shallow chemocline in the Mesoproterozoic ocean: evidence from carbon-sulfur-iron relationships. Precambrian Research 257, 94-108.

). Strata are exposed in the El Mreiti region of Mauritania and are stratigraphically equivalent to pericratonic deposits of the Atar Group, which are exposed near the craton edges in the Adrar Uplift of Mauritania and to the east in Mali and Algeria. The El Mreiti Group is disconformably bounded by dominantly siliciclastic strata of the underlying Char Group and the overlying Assabet el Hassiane Group. Deposition in the El Mreiti Group began after formation of a regional peneplain and progressive marine transgression across the craton (Bertrand-Sarfati and Moussine-Pouchkine, 1988Bertrand-Sarfati, J., Moussine-Pouchkine, A. (1988) Is cratonic sedimentation consistent with available models? An example from the Upper Proterozoic of the West African craton. Sedimentary Geology 58, 255-276.

; Benan and Deynoux, 1998Benan, C.A.A., Deynoux, M. (1998) Facies analysis and sequence stratigraphy of Neoproterozoic platform deposits in Adrar of Mauritania, Taoudeni Basin, West Africa. Geologische Rundschau 87, 283-330.

) – beginning with sandstone, siltstone, and shale of the Khatt Formation. Carbonate deposition began in the overlying En Nesoar Formation, which consists of intertidal to subtidal dolostone and shale. A major flooding surface is recognised at the base of the overlying Touirist Formation, above which strata are comprised of alternating clayey, stromatolitic limestone and organic-rich shale deposited near fair weather wave base. Re-Os geochronology on organic-rich shale of the En Nesoar and Touirist formations yields ages of 1109 ± 22 Ma, 1107 ± 12 Ma, and 1105 ± 37 Ma (Rooney et al., 2010Rooney, A.D., Selby, D., Houzay, J.P., Renne, P.R. (2010) Re - Os geochronology of a Mesoproterozoic sedimentary succession, Taoudeni Basin, Mauritania: implications for basin-wide correlations and Re - Os organic-rich sediments systematics. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 289, 486-496.

), which are consistent with muted carbon isotope variability that is characteristic of global carbon isotope trends in the late Mesoproterozoic Era (Kah et al., 1999Kah, L.C., Sherman, A.B., Narbonne, G.M., Kaufman, A.J., Knoll, A.H. (1999) d13C stratigraphy of the Proterozoic Bylot Supergroup, northern Baffin Island: implications for regional lithostratigraphic correlations. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 36, 313-332.

, 2012Kah, L.C., Bartley, J.K., Teal, D.A. (2012) Chemostratigraphy of the late Mesoproterozoic Atar Group, Taoudeni Basin, Mauritania: muted isotopic variability, facies correlation, and global isotopic trends. Precambrian Research 200-203, 82-103.

; Gilleaudeau and Kah, 2013aGilleaudeau, G.J., Kah, L.C. (2013a) Carbon isotope records in a Mesoproterozoic epicratonic sea: carbon cycling in a low-oxygen world. Precambrian Research 228, 85-101.

). Palaeoenvironments shoal at the base of the overlying Aguelt el Mabha Formation, which is characterised by silty and clayey limestone deposited above fair weather wave base. Palaeoenvironments deepen again through the overlying Gouamir and Tenoumer formations, which are comprised of increasingly pure limestone deposited at or below fair weather wave base. Overlying units of the El Mreiti Group have been erosionally removed in the north-central Taoudeni Basin so that the Assabet el Hassiane Group lies disconformably above the Tenoumer Formation in the study area (Kah et al., 2012Kah, L.C., Bartley, J.K., Teal, D.A. (2012) Chemostratigraphy of the late Mesoproterozoic Atar Group, Taoudeni Basin, Mauritania: muted isotopic variability, facies correlation, and global isotopic trends. Precambrian Research 200-203, 82-103.

; Gilleaudeau and Kah, 2013aGilleaudeau, G.J., Kah, L.C. (2013a) Carbon isotope records in a Mesoproterozoic epicratonic sea: carbon cycling in a low-oxygen world. Precambrian Research 228, 85-101.

). El Mreiti Group strata have not been subjected to regional metamorphism, and contact metamorphism is spatially confined to areas immediately adjacent to Mesozoic diabase intrusions, which do not intersect the drill core sampled in this study (Gilleaudeau and Kah, 2013aGilleaudeau, G.J., Kah, L.C. (2013a) Carbon isotope records in a Mesoproterozoic epicratonic sea: carbon cycling in a low-oxygen world. Precambrian Research 228, 85-101.

,bGilleaudeau, G.J., Kah, L.C. (2013b) Oceanic molybdenum drawdown by epeiric sea expansion in the Mesoproterozoic. Chemical Geology 356, 21-37.

, 2015Gilleaudeau, G.J., Kah, L.C. (2015) Heterogeneous redox conditions and a shallow chemocline in the Mesoproterozoic ocean: evidence from carbon-sulfur-iron relationships. Precambrian Research 257, 94-108.

). Fresh core samples were collected from drill core F4 that intersected the Khatt, En Nesoar, Touirist, Aguelt el Mabha, and Gouamir formations just west of El Mreiti, Mauritania (~23.5° N, 7.85° W).Vazante Group, Brazil

The Vazante Group – deposited along the western margin of the São Francisco craton (Minas Gerais, Brazil) – is comprised of dominantly dolomitic strata that reach up to 2 km in thickness in the eastern part of the Brasília Fold Belt (Azmy et al., 2001

Azmy, K., Veizer, J., Misi, A., de Oliveira, T.F., Sanches, A.L., Dardenne, M.A. (2001) Dolomitization and isotope stratigraphy of the Vazante Formation, São Francisco Basin, Brazil. Precambrian Research 112, 303-329.

). Vazante Group stratigraphy has recently been revised based on field observation of a thrust fault that juxtaposes late Mesoproterozoic strata above Neoproterozoic strata of the St. Antônio do Bonito and Rocinha formations (Geboy et al., 2013Geboy, N.J., Kaufman, A.J., Walker, R.J., Misi, A., de Oliveira, T.F., Miller, K.E., Azmy, K., Kendall, B., Poulton, S.W. (2013) Re-Os constraints and new observations of Proterozoic glacial deposits in the Vazante Group, Brazil. Precambrian Research 238, 199-213.

). This observation reconciles previously documented stratigraphic inversion of U-Pb detrital zircon ages, and in this study, we focus only on Mesoproterozoic strata that lie above the fault horizon. This interval begins with the Lagamar Formation, which consists of subtidal silty dolostone with stromatolitic (Conophyton) horizons. This unit is overlain by organic-rich shale of the Serra do Garrote Formation, which has been dated using Re-Os geochronology at 1354 ± 88 Ma (Geboy et al., 2013Geboy, N.J., Kaufman, A.J., Walker, R.J., Misi, A., de Oliveira, T.F., Miller, K.E., Azmy, K., Kendall, B., Poulton, S.W. (2013) Re-Os constraints and new observations of Proterozoic glacial deposits in the Vazante Group, Brazil. Precambrian Research 238, 199-213.

). Above this lies the Serra do Poco Verde and Morro do Calcario formations, which consist of relatively pure dolostone with discrete silty intervals and microbial lamination deposited in supratidal to intertidal environments (Azmy et al., 2008Azmy, K., Kendall, B., Creaser, R.A., Heaman, L., de Oliveira, T.F. (2008) Global correlation of the Vazante Group, São Francisco Basin, Brazil: Re-Os and U-Pb radiometric age constraints. Precambrian Research 164, 160-172.

). At the top of the Morro do Calcario Formation, a discrete diamictite interval is observed that consists of both rounded and angular cobbles and boulders that are often faceted, as well as dropstone-laden mudstone containing pseudomorphs of glendonite – a cold water carbonate mineral taken as one line of evidence for a glacial origin of Vazante Group diamictites (Olcott et al., 2005Olcott, A.N., Sessions, A.L., Corsetti, F.A., Kaufman, A.J., de Oliveira, T.F. (2005) Biomarker evidence for photosynthesis during Neoproterozoic glaciation. Science 310, 471-474.

; Geboy et al., 2013Geboy, N.J., Kaufman, A.J., Walker, R.J., Misi, A., de Oliveira, T.F., Miller, K.E., Azmy, K., Kendall, B., Poulton, S.W. (2013) Re-Os constraints and new observations of Proterozoic glacial deposits in the Vazante Group, Brazil. Precambrian Research 238, 199-213.

). The base of the diamictite interval erosionally incises underlying strata, and in some cases, two separate diamictite intervals are observed (one at the top of the Serra do Poco Verde Formation), although these relationships seem to be regionally variable (Olcott et al., 2005Olcott, A.N., Sessions, A.L., Corsetti, F.A., Kaufman, A.J., de Oliveira, T.F. (2005) Biomarker evidence for photosynthesis during Neoproterozoic glaciation. Science 310, 471-474.

; Azmy et al., 2009Azmy, K., Sylvester, P., de Oliveira, T.F. (2009) Oceanic redox conditions in the Late Mesoproterozoic recorded in the upper Vazante Group carbonates of the São Francisco Basin, Brazil: evidence from stable isotopes and REEs. Precambrian Research 168, 259-270.

; Geboy et al., 2013Geboy, N.J., Kaufman, A.J., Walker, R.J., Misi, A., de Oliveira, T.F., Miller, K.E., Azmy, K., Kendall, B., Poulton, S.W. (2013) Re-Os constraints and new observations of Proterozoic glacial deposits in the Vazante Group, Brazil. Precambrian Research 238, 199-213.

). Re-Os geochronology on organic-rich diamictite horizons yields ages of 1100 ± 77 Ma (Azmy et al., 2008Azmy, K., Kendall, B., Creaser, R.A., Heaman, L., de Oliveira, T.F. (2008) Global correlation of the Vazante Group, São Francisco Basin, Brazil: Re-Os and U-Pb radiometric age constraints. Precambrian Research 164, 160-172.

) and 1112 ± 50 Ma (Geboy et al., 2013Geboy, N.J., Kaufman, A.J., Walker, R.J., Misi, A., de Oliveira, T.F., Miller, K.E., Azmy, K., Kendall, B., Poulton, S.W. (2013) Re-Os constraints and new observations of Proterozoic glacial deposits in the Vazante Group, Brazil. Precambrian Research 238, 199-213.

), supporting a late Mesoproterozoic age for the Vazante Group. Disconformably overlying the Morro do Calcario Formation is post-glacial subtidal argillaceous dolostone of the Lapa Formation, which represents the top of the Vazante Group succession. During the Brasiliano-Pan African orogeny, regional metamorphism did not exceed lowermost greenschist facies (Azmy et al., 2008Azmy, K., Kendall, B., Creaser, R.A., Heaman, L., de Oliveira, T.F. (2008) Global correlation of the Vazante Group, São Francisco Basin, Brazil: Re-Os and U-Pb radiometric age constraints. Precambrian Research 164, 160-172.

) and evidence for contact metamorphism is absent in the study area. Fresh core samples were collected from drill cores CMM-500, CMM-279, and MASW-01 that intersected the Serra do Poco Verde, Morro do Calcario, and Lapa formations northwest of Unaí, Brazil (~16.3° S, 47.1° W).Analytical Methods

Sample preparation

Outcrop and drill core samples were first slabbed using a diamond saw in order to remove weathered surfaces. Slabs were then washed in 2 M HCl to etch the surfaces that had been in contact with the saw blade. Next, slabs were wrapped in plastic and crushed to chips manually with a hammer, with the plastic wrapping designed to avoid contact of samples with the hammer. Lastly, rock chips were crushed to a fine powder using an agate mixer mill.

Chromium separation

Using modifications on a previously described procedure (Frei et al., 2011

Frei, R., Gaucher, C., Døssing, L.N., Sial, A.N. (2011) Chromium isotopes in carbonates - a tracer for climate change and for reconstructing the redox state of ancient seawater. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 312, 114-125.

), ~1 gram of powdered sample was spiked with 50Cr-54Cr double spike (Schoenberg et al., 2008Schoenberg, S., Zink, M., Staubwasser, M., von Blanckenburg, F. (2008) The stable Cr isotope inventory of solid Earth reservoirs determine by double spike MC-ICP-MS. Chemical Geology 249, 294-306.

) to a 4:1 sample to spike Cr ratio. Spiked samples were then dissolved for ~30 minutes in either 0.5 M or 2 M HCl with the sample mixed through the acid using a shaker table. After dissolution, samples were centrifuged to remove insoluble residue and the supernatant was pipetted into a Teflon beaker that was pre-cleaned with aqua regia. Teflon beakers were placed uncovered on a hot plate and the supernatant was dried down overnight at 120 °C. Next, the sample was re-dissolved in aqua regia (made from double-distilled HCl and HNO3) and, again, dried down overnight at 120 °C to ensure sample/spike homogenisation. Samples were then re-dissolved in 0.1 M HCl, and ~1 mL of (NH4)S2O8 was added to each beaker as an oxidising agent. Beakers were capped and heated in a microwave for ~30 minutes (or until boiling was observed) to oxidise Cr(III) to Cr(VI). Oxidised samples were then passed over an anion exchange column charged with 2 mL of Dowex AG 1 × 8 anion resin (100-200 mesh, pre-conditioned with 6 M HCl), during which Cr(VI)-oxyanions are adsorbed to the resin surface by exchange with chloride ions. Cr was then released from the anion resin by reduction to Cr(III) using 2 M double-distilled HNO3 and H2O2. The resulting liquid was dried down overnight at 120 °C and the sample was re-dissolved in 1 mL of 6 M double-distilled HCl before being passed over a second anion exchange column – also charged with 2 mL of Dowex AG 1 × 8 anion resin (100-200 mesh, pre-conditioned with 6 M HCl) – designed specifically for removal of iron (Fe). Fe removal is critical because of isobaric interference between 54Fe and 54Cr during isotopic analysis. Again, the resulting liquid was dried down overnight at 120 °C and samples were re-dissolved in 200 μL of 6 M double-distilled HCl. After dilution with 2.2 mL of ultrapure MQ water, samples were passed over a cation exchange column charged with 2 mL of Dowex AG50W-X8 cation resin (200-400 mesh, pre-conditioned with 0.5 M HCl). Cation exchange is used to separate Cr from major matrix elements such as Ca, Mg, Mn, Al, and residual Fe. The resulting liquid was dried down overnight at 120 °C and the precipitate was then ready for loading onto a Re filament for Cr-isotopic analysis.Thermal ionisation mass spectrometry (TIMS)

All Cr-isotope measurements were performed at the University of Copenhagen on an IsotopX Ltd. IsoProbe T or Phoenix thermal ionisation mass spectrometer (TIMS) equipped with eight Faraday collectors that allow simultaneous collection of all four chromium beams (50Cr+, 52Cr+, 53Cr+, 54Cr+) together with 49Ti+, 51V+, and 56Fe+ as monitors for small interferences from other isotopes of these same elements. Final precipitates after Cr separation were loaded onto outgassed Re filaments along with a mixture of 3 μL of silicic acid, 1 μL of 0.5 M H3BO3, and 1 μL of 0.5 M H3PO4. Samples were analysed at temperatures ranging from 1000-1250 °C with 52Cr beam intensities between 200 and 1000 mV. One run consisted of 120 cycles (grouped into 24 blocks of 5 cycles each with 10 second signal integration periods) and at least two (but as many eight) runs were performed for each sample. The final isotopic composition of a sample is reported as the average of these repeated analyses with standard errors reported as the standard deviation (s.d.) of isotopic values divided by the square root of n (the number of runs). Isotopic compositions are reported in per mil (‰) notation relative to the certified Cr-isotope standard NIST SRM 979:

Eq. S-1

δ53Cr(‰) = ((53Cr/52Crsample)/(53Cr/52CrNIST SRM 979) - 1) • 1000

Standard errors for our samples were consistently <0.05 ‰. Initial sample and spike weights were also used to determine the Cr concentration of each sample (in ppm) from TIMS data. Blanks produced consistently <15 ng of Cr, which is negligible compared to our samples that contained between ~500 ng and 6 μg of Cr.

The external reproducibility of our measurements was assessed by comparing long-term average δ53Cr values for NIST SRM 979 and NIST 3112a measured on the IsoProbe T and the Phoenix to accepted values from other laboratories (Schoenberg et al., 2008

Schoenberg, S., Zink, M., Staubwasser, M., von Blanckenburg, F. (2008) The stable Cr isotope inventory of solid Earth reservoirs determine by double spike MC-ICP-MS. Chemical Geology 249, 294-306.

). Our results over >5 years of analysis indicate that standard values are measured 0.09 ‰ lower on the IsoProbe T and 0.08 ‰ higher on the Phoenix compared to accepted values. As a result, 0.09 ‰ was added to raw δ53Cr values produced on the IsoProbe T and 0.08 ‰ was subtracted from raw δ53Cr values produced on the Phoenix. During the course of the runs presented in this study, NIST SRM 979 and NIST 3112a values were reproduced with analytical uncertainties <0.05 ‰. Internal reproducibility was assessed by dissolving certified carbonate standards JLs-1 (Triassic limestone) and JDo-1 (Permian dolostone) and measuring their Cr-isotopic composition along with samples from each run. Measured δ53Cr values were +1.80 ± 0.06 ‰ for JLs-1 and +1.64 ± 0.03 ‰ for JDo-1, both of which are in good agreement with published values (Schoenberg et al., 2008Schoenberg, S., Zink, M., Staubwasser, M., von Blanckenburg, F. (2008) The stable Cr isotope inventory of solid Earth reservoirs determine by double spike MC-ICP-MS. Chemical Geology 249, 294-306.

).Major and trace element abundances

Ca, Mg, Fe, Sr, Mn, and Al concentrations were measured by ICP-OES at the University of Copenhagen on splits of the same sample solutions used for Cr-isotopic analysis. Solutions were diluted with 2 % HNO3 to a Ca concentration of ~50 ppm, and limestone and dolostone samples were analysed separately along with three separate calibration solutions designed to mimic the range of element concentrations expected in limestone and dolostone samples. Duplicates of certified carbonate standards (JLs-1 and JDo-1) were measured every nine samples and analytical precision was determined using the reproducibility of molar element to Ca ratios in the standards. Measured values are in good agreement with published values for both JLs-1 and JDo-1. The sum of cation concentrations relative to initial sample weight was used to determine the carbonate content of each sample. Carbonate content was then used to correct measured concentrations of Ca, Mg, Fe, Sr, and Mn to reflect concentrations specifically in carbonate. Ti and Zr abundances were measured by ICP-MS at the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland (GEUS). 25-35 mg of sample powder was dissolved in 2 mL of either 0.5 M or 2 M HCl and final solutions were diluted up to 10 mL with ultrapure MQ water. Samples were analysed using the USGS BHVO-1 (basalt, Hawaiian Volcanic Observatory) standard as a reference material along with dissolved carbonate standards (JLs-1 and JDo-1). Measured Ti and Zr concentrations for the BHVO-1 standard are in good agreement with published values.

Assessment of Diagenesis

Petrography

Conventional petrography in plane- and cross-polarised light was used as a first measure of diagenesis in the carbonate successions investigated in this study. Primary and early diagenetic carbonate matrix phases are fine-grained (micritic to microsparitic) and lack planar, interlocking grain boundaries (Longman, 1980

Longman, M.W. (1980) Carbonate diagenetic textures from near surface diagenetic environments. AAPG Bulletin 64, 461-487.