Distribution of Zn isotopes during Alzheimer’s disease

Affiliations | Corresponding Author | Cite as | Funding informationKeywords: zinc isotopes, Alzheimer's disease, medical geochemistry, brain, beta amyloid

- Share this article

Article views:8,553Cumulative count of HTML views and PDF downloads.

- Download Citation

- Rights & Permissions

Abstract

Figures and Tables

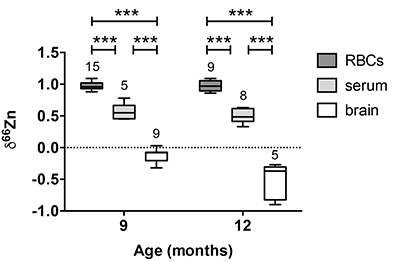

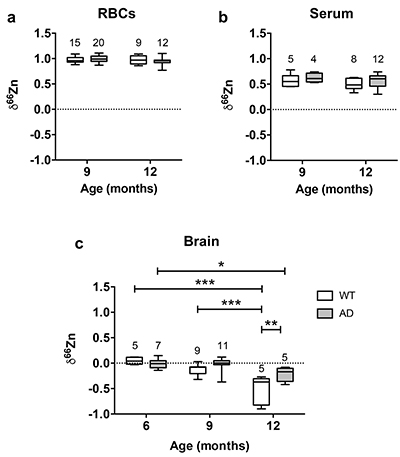

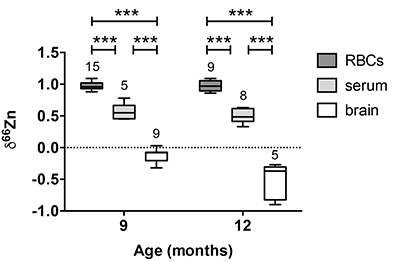

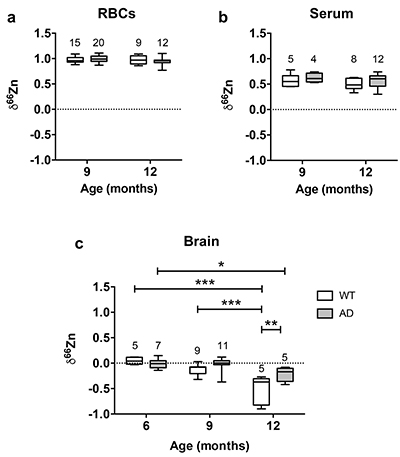

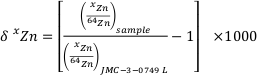

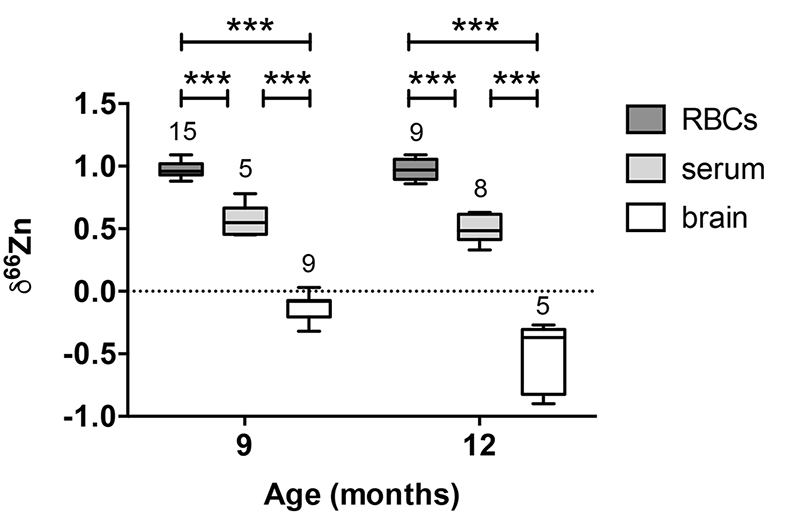

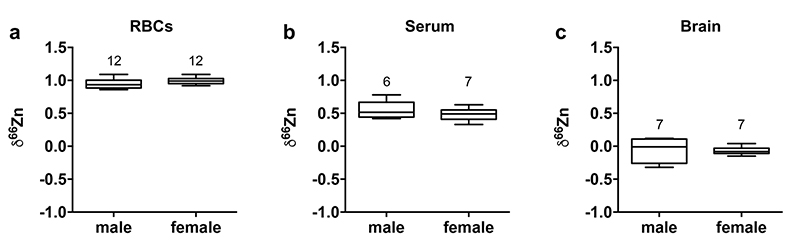

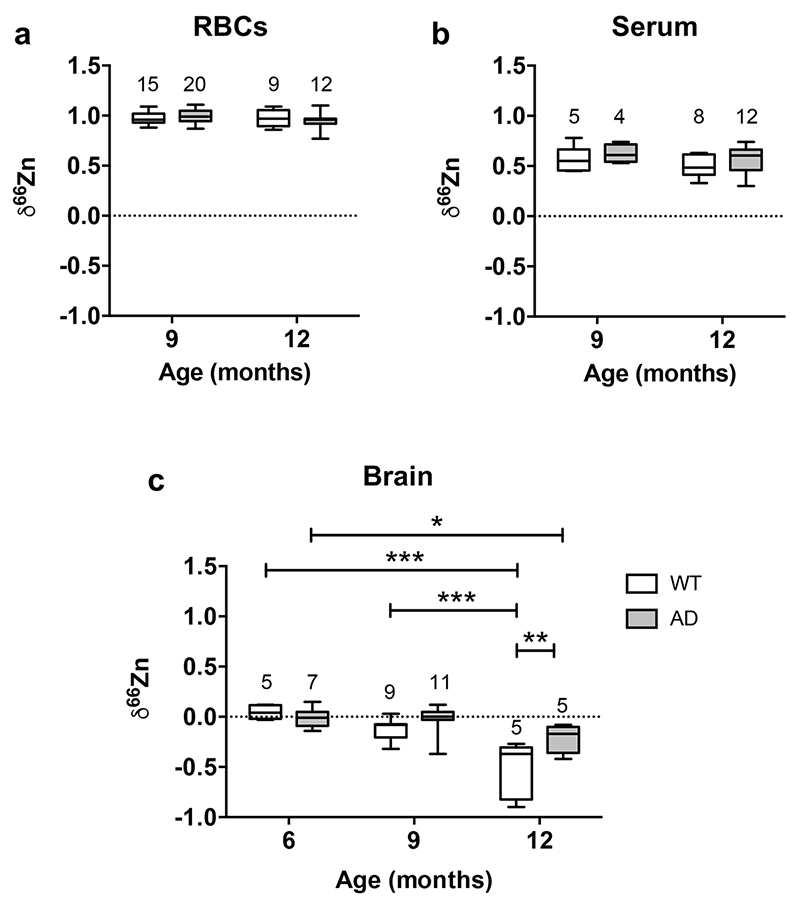

Figure 1 δ66Zn of brains, serum and RBCs of WT mice over time. Boxes extend from the 25th and 75th percentile, the line in the middle of the box represents the median, and the whiskers show the minimum and the maximum. Two-way ANOVA was performed to compare groups (F value: 11.95, p < 0.0001), followed by Sidak’s multiple comparison test to compare the means between organs for each time point (*** indicates statistical difference, p < 0.001). |  Figure 2 Effect of the sex on δ66Zn. Data show pooled results from 9- and 12-month-old WT mice for (a) RBCs and (b) serum, and (c) 6- and 9-month-old WT mice for brain. Student’s t-test showed no significant differences in any organ between males and females. |  Figure 3 Effect of Alzheimer’s disease on δ66Zn. Data show results from WT and AD mice for (a) RBCs, (b) serum and (c) brain. Two-way ANOVA showed no significant effect of age or genotype for RBCs (F = 1.953, p = 0.17; a) or serum (F = 0.008, p = 0.92; b), and showed significant effect of age and genotype (F = 4.288, p = 0.0214) for brain (c). Sidak’s multiple comparison tests were run to compare groups for brain samples: asterisks indicate significant difference between groups (*: p < 0.05; **: p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001). |

| Figure 1 | Figure 2 | Figure 3 |

Supplementary Figures and Tables

Table S-1 Zinc isotopic composition of the different samples analysed in this study. |  Table S-2 Average isotopic composition of brain, RBC, and serum samples measured in this study. |

| Table S-1 | Table S-2 |

top

Letter

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common type of dementia and one of the main causes of death in high-income countries (GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators, 2015

GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators (2015) Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 385, 117–171.

). The main physiological hallmarks of AD are the formation of senile plaques by extracellular deposits of amyloid β (Aβ) fibrils. In addition, the homeostasis of metals, such as Zn, is dysregulated in AD patients (e.g., Baum et al., 2010Baum, L., Chan, I.H.S., Cheung, S.K.K., Goggins, W.B., Mok, V., Lam, L., Leung, V., Hui, E., Ng, C., Woo, J., Chiu, H.F.K., Zee, B.C.Y., Cheng, W., Chan, M.H., Szeto, S., Lui, V., Tsoh, J., Bush, A.I., Lam, C.W.K., Kwok, T. (2010) Serum zinc is decreased in Alzheimer's disease and serum arsenic correlates positively with cognitive ability. Biometals 23, 173–179.

; Szewczyk, 2013Szewczyk, B. (2013) Zinc homeostasis and neurodegenerative disorders. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 5, 12.

). While the full role of Zn in AD is not totally clear yet, there is much evidence that Zn is involved in the formation of Aβ leading to an enrichment of Zn in the neocortex of AD patients (e.g., Miller et al., 2006Miller, L.M., Wang, Q., Telivala, T.P., Smith, R.J., Lanzirotti, A., Miklossy, J. (2006) Synchrotron-based infrared and X-ray imaging shows focalized accumulation of Cu and Zn co-localized with beta-amyloid deposits in Alzheimer's disease. Journal of Structural Biology 155, 30–37.

; Religa et al., 2006Religa, D., Strozyk, D., Cherny, R.A., Volitakis, I., Haroutunian, V., Winblad, B., Naslund, J., Bush, A.I. (2006) Elevated cortical zinc in Alzheimer disease. Neurology 67, 69–75.

).The dysregulation of Zn homeostasis associated with AD may be utilised as a new diagnosis tool. Alterations in the concentration of Zn in the AD brain may be propagated to other body organs and fluids via red blood cells (RBCs) and/or serum. Following this approach, several studies have compared the Zn concentration in the serum of control and AD patients with inconsistent results (Baum et al., 2010

Baum, L., Chan, I.H.S., Cheung, S.K.K., Goggins, W.B., Mok, V., Lam, L., Leung, V., Hui, E., Ng, C., Woo, J., Chiu, H.F.K., Zee, B.C.Y., Cheng, W., Chan, M.H., Szeto, S., Lui, V., Tsoh, J., Bush, A.I., Lam, C.W.K., Kwok, T. (2010) Serum zinc is decreased in Alzheimer's disease and serum arsenic correlates positively with cognitive ability. Biometals 23, 173–179.

). Elemental abundance variations in the serum may be subjected to many factors unrelated to AD, such as intestinal absorption of Zn (Vasto et al., 2007Vasto, S., Mocchegiani, E., Malavolta, M., Cuppari, I., Listì, F., Nuzzo, D., Ditta, V., Candore, G., Caruso, C. (2007) Zinc and inflammatory/immune response in aging. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 100, 111–122.

), which potentially explain the result inconsistencies.The stable isotopic composition of Zn naturally varies between body organs (Balter et al., 2010

Balter, V., Zazzo, A., Moloney, A.P., Moynier, F., Schmidt, O., Monahan, F.J., Albarede, F. (2010) Bodily variability of zinc natural isotope abundances in sheep. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry 24, 605–612.

, 2013Balter, V., Lamboux, A., Zazzo, A., Telouk, P., Leverrier, Y., Marvel, J., Moloney, A.P., Monahan, F.J., Schmidt, O., Albarede, F. (2013) Contrasting Cu, Fe, and Zn isotopic patterns in organs and body fluids of mice and sheep, with emphasis on cellular fractionation. Metallomics 5, 1470–1482.

; Moynier et al., 2013Moynier, F., Fujii, T., Shaw, A., Le Borgne, M. (2013) Heterogeneous distribution of natural zinc isotopes in mice. Metallomics 5, 693-699.

; Jaouen et al., 2016Jaouen, K., Beasley, M., Schoeninger, M., Hublin, J., Richards, M. (2016) Zinc isotope ratios of bones and teeth as new dietary indicators: results from a modern food web (Koobi Fora, Kenya). Scientific Reports 6, 26281.

). In stable isotope geochemistry, isotope ratios are usually reported as a relative deviation from a standard. In the case of Zn, all the data are reported using the δxZn defined as:Eq. 1

where x = 66 or 68. The reference material used is the Zn “Lyon” standard JMC 3-0749 L (e.g., see Moynier et al., 2017

Moynier, F., Vance, D., Fujii, T., Savage, P. (2017) The isotope geochemistry of zinc and copper. Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry 82, 543–600.

for review).In particular, RBCs are enriched by ~0.5 ‰ (for δ66Zn) when compared to serum, and up to ~1 ‰ when compared to the brain (Balter et al., 2010

Balter, V., Zazzo, A., Moloney, A.P., Moynier, F., Schmidt, O., Monahan, F.J., Albarede, F. (2010) Bodily variability of zinc natural isotope abundances in sheep. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry 24, 605–612.

, 2013Balter, V., Lamboux, A., Zazzo, A., Telouk, P., Leverrier, Y., Marvel, J., Moloney, A.P., Monahan, F.J., Schmidt, O., Albarede, F. (2013) Contrasting Cu, Fe, and Zn isotopic patterns in organs and body fluids of mice and sheep, with emphasis on cellular fractionation. Metallomics 5, 1470–1482.

; Moynier et al., 2013Moynier, F., Fujii, T., Shaw, A., Le Borgne, M. (2013) Heterogeneous distribution of natural zinc isotopes in mice. Metallomics 5, 693-699.

). Differences in isotope ratio were not altered by gender, genetic background or age (up to 16 weeks) in multiple organs of mice (Moynier et al., 2013Moynier, F., Fujii, T., Shaw, A., Le Borgne, M. (2013) Heterogeneous distribution of natural zinc isotopes in mice. Metallomics 5, 693-699.

). This difference between organs is explained by isotope fractionation at equilibrium between different bonding environments of Zn where isotopically light Zn is enriched in cysteine-rich proteins in the brain (metallothionein) and isotopically heavy Zn enriched in histidine-rich proteins in RBCs (carbonic anhydrase) (Moynier et al., 2013Moynier, F., Fujii, T., Shaw, A., Le Borgne, M. (2013) Heterogeneous distribution of natural zinc isotopes in mice. Metallomics 5, 693-699.

). Since the AD deregulates the Zn homeostasis, we reasoned that the ~0.5 ‰ Zn isotopic difference between serum and brain of normal mice could be used to search for modifications of the isotopic balance during the development of the AD. For example, Zn is principally bound to histidine in amyloid-beta that are formed during the AD (Faller and Hureau, 2009Faller, P., Hureau, C. (2009) Bioinorganic chemistry of copper and zinc ions coordinated to amyloid-beta peptide. Dalton Transactions, 1080–1094.

), which should enrich the AD brains in isotopically heavy Zn compared to controls and possibly deplete the serum in the lighter isotopes.Here we tested whether the distribution of Zn isotopes is altered in mice with late stage AD and determined how early disease anomalies in Zn isotopes could be detected. We present the Zn isotopic composition of transgenic APPswe/PSEN1dE9 and wild type (WT) controls for which we have collected the brain, RBCs and serum at the early stage (6 months) and late stage of AD (9 and 12 months) (Jankowsky et al., 2004

Jankowsky, J.L., Fadale, D.J., Anderson, J., Xu, G.M., Gonzales, V., Jenkins, N.A., Copeland, N.G., Lee, M.K., Younkin, L.H., Wagner, S.L., Younkin, S.G., Borchelt, D.R. (2004) Mutant presenilins specifically elevate the levels of the 42 residue beta-amyloid peptide in vivo: evidence for augmentation of a 42-specific gamma secretase. Human Molecular Genetics 13, 159–170.

; Garcia-Alloza et al., 2006Garcia-Alloza, M., Robbins, E.M., Zhang-Nunes, S.X., Purcell, S.M., Betensky, R.A., Raju, S., Prada, C., Greenberg, S.M., Bacskai, B.J., Frosch, M.P. (2006) Characterization of amyloid deposition in the APPswe/PS1dE9 mouse model of Alzheimer disease. Neurobiology of Disease 24, 516–524.

) to assess how AD affects the balance of zinc isotopes in the brain.Brains are enriched in lighter isotopes compared to blood. The method, sample descriptions and Zn isotopic data for 128 samples are reported in the Supplementary Information. The average of the different group of samples sorted by ages are reported in Table S-2. All the mice were fed the same diet (water and dry food) from birth and were housed in the same animal facility as our previous study (Moynier et al., 2013

Moynier, F., Fujii, T., Shaw, A., Le Borgne, M. (2013) Heterogeneous distribution of natural zinc isotopes in mice. Metallomics 5, 693-699.

); we can therefore directly compare the isotopic composition of the two studies. Assuming that the Zn isotopic composition of the mouse food does not vary between different batches, we can use the value from our previous study: δ66Zn = 0.30 ± 0.10 ‰. On average, the RBCs were isotopically heavier (δ66Zn ~+1 ‰) than serum (δ66Zn ~+0.5 ‰) and brains (-0.5 < δ66Zn < 0 ‰) (Fig. 1). These results are in excellent agreement with what we previously reported (Moynier et al., 2013Moynier, F., Fujii, T., Shaw, A., Le Borgne, M. (2013) Heterogeneous distribution of natural zinc isotopes in mice. Metallomics 5, 693-699.

).

Figure 1 δ66Zn of brains, serum and RBCs of WT mice over time. Boxes extend from the 25th and 75th percentile, the line in the middle of the box represents the median, and the whiskers show the minimum and the maximum. Two-way ANOVA was performed to compare groups (F value: 11.95, p < 0.0001), followed by Sidak’s multiple comparison test to compare the means between organs for each time point (*** indicates statistical difference, p < 0.001).

Alzheimer’s disease does not affect the isotopic ratio in the blood. The values obtained for RBCs were extremely homogeneous (δ66Zn = 0.97 ± 0.07 ‰, n = 24) for WT, with no dependence on sex (Fig. 2a) or age (Fig. 1, p > 0.05 with Sidak’s multiple comparison test). The values for the serum were slightly more variable (δ66Zn = 0.52 ± 0.12 ‰ for WT, n = 13), with no effect of sex (Fig. 2b), or age (Fig. 1; p > 0.05 with Sidak’s multiple comparison test).

Finally, there was no effect of the genotype on the isotopic composition of the blood compartments, as there was no significant difference between AD mice and WT mice in RBCs (Fig. 3a) and serum (Fig. 3b).

Figure 2 Effect of the sex on δ66Zn. Data show pooled results from 9- and 12-month-old WT mice for (a) RBCs and (b) serum, and (c) 6- and 9-month-old WT mice for brain. Student’s t-test showed no significant differences in any organ between males and females.

Figure 3 Effect of Alzheimer’s disease on δ66Zn. Data show results from WT and AD mice for (a) RBCs, (b) serum and (c) brain. Two-way ANOVA showed no significant effect of age or genotype for RBCs (F = 1.953, p = 0.17; a) or serum (F = 0.008, p = 0.92; b), and showed significant effect of age and genotype (F = 4.288, p = 0.0214) for brain (c). Sidak’s multiple comparison tests were run to compare groups for brain samples: asterisks indicate significant difference between groups (*: p < 0.05; **: p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001).

Alzheimer’s disease delays brain enrichment in lighter isotopes over time. The δ66Zn of the brain showed the largest range of variation among the organs, with an average of -0.19 ± 0.27 ‰; n = 19 for WT mice. Sex had no significant impact on the isotopic composition of the brain (Fig. 2c). But the variations were correlated with mouse age (Figs. 1 and 3c) with a decrease in the δ66Zn in comparing 6-month-old to 12-month-old mice.

Even if brains also got enriched in the lighter isotopes over time in AD mice, they clearly displayed a heavier Zn isotopic ratio than WT mice in 12-month-old animals (p < 0.01, Sidak’s multiple comparison test) and therefore AD brains are isotopically different from WT brains. These data show that AD has an effect on the Zn isotopic ratio in the brain.

Effect of aging on the Zn isotopic composition of organs and its implication for the dysregulation of the homeostasis of Zn. The youngest mice that we analysed in this study are 6 months old, and have Zn isotopic composition of the brains (0.05 ± 0.07 ‰; n = 5) identical to the mice measured in previous studies (-0.03 ± 0.08 ‰; n = 14, Moynier et al., 2013

Moynier, F., Fujii, T., Shaw, A., Le Borgne, M. (2013) Heterogeneous distribution of natural zinc isotopes in mice. Metallomics 5, 693-699.

). This suggests that up to 6 months there is no change in the Zn isotopic composition of the brain. However, brains of 9- and 12-month-old WT and AD mice had enrichment of the lighter isotopes (Fig. 3c). This enrichment in the lighter isotopes can potentially be used to understand what processes associated with Zn are changing with normal aging.The changes in δ66Zn of brains with age must be related to the deterioration of brain cells. It is well known that aging brains display several changes, such as a decrease of the number of neurons as well as a decline in the cell-to-cell communications due to a deterioration of the synaptic contact zone (Casoli et al., 1996

Casoli, T., Spagna, C., Fattoretti, P., Gesuita, R., Bertoni-Freddari, C. (1996) Neuronal plasticity in aging: a quantitative immunohistochemical study of GAP-43 distribution in discrete regions of the rat brain. Brain Research 714, 111–117.

; Bertoni-Freddari et al., 2008Bertoni-Freddari, C., Fattoretti, P., Casoli, T., Di Stefano, G., Giorgetti, B., Balietti, M. (2008) Brain aging: The zinc connection. Experimental Gerontology 43, 389–393.

). In the brain, Zn is mostly distributed within three reservoirs in three different species (Szewczyk, 2013Szewczyk, B. (2013) Zinc homeostasis and neurodegenerative disorders. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 5, 12.

): 1) sequestered in the presynaptic vesicles of neurons co-located with glutamate (Frederickson, 1989Frederickson, C.J. (1989) Neurobiology of zinc and zinc-containing neurons. International Review of Neurobiology 31, 145–238.

; Frederickson et al., 2000Frederickson, C.J., Suh, S.W., Silva, D., Frederickson, C.J., Thompson, R.B. (2000) Importance of zinc in the central nervous system: the zinc-containing neuron. Journal of Nutrition 130, 1471S–1483S.

); 2) bound to intra-cellular proteins such as metallothioneins (MT) (Krezel et al., 2007Krezel, A., Hao, Q., Maret, W. (2007) The zinc/thiolate redox biochemistry of metallothionein and the control of zinc ion fluctuations in cell signaling. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 463, 188–200.

), ZIP and membranous transporter proteins (ZnT) (Huang and Tepaamorndech, 2013Huang, L., Tepaamorndech, S. (2013) The SLC30 family of zinc transporters - a review of current understanding of their biological and pathophysiological roles. Molecular Aspects of Medicine 34, 548–560.

); and 3) unbound ions in the cytoplasm as hydrated Zn2+ (Frederickson et al., 2000Frederickson, C.J., Suh, S.W., Silva, D., Frederickson, C.J., Thompson, R.B. (2000) Importance of zinc in the central nervous system: the zinc-containing neuron. Journal of Nutrition 130, 1471S–1483S.

).The exact behaviour and role of Zn during normal brain aging is still unclear: some studies showed that unbound Zn2+ increases (Bertoni-Freddari et al., 2008

Bertoni-Freddari, C., Fattoretti, P., Casoli, T., Di Stefano, G., Giorgetti, B., Balietti, M. (2008) Brain aging: The zinc connection. Experimental Gerontology 43, 389–393.

) whereas other studies suggest that it decreases (Mocchegiani et al., 2005Mocchegiani, E., Bertoni-Freddari, C., Marcellini, F., Malavolta, M. (2005) Brain, aging and neurodegeneration: role of zinc ion availability. Progress in Neurobiology 75, 367–390.

). Possible explanations for the decrease of free Zn would be the excessive pre-synaptic release of glutamate (Saito et al., 2000Saito, T., Takahashi, K., Nakagawa, N., Hosokawa, T., Kurasaki, M., Yamanoshita, O., Yamamoto, Y., Sasaki, H., Nagashima, K., Fujita, H. (2000) Deficiencies of hippocampal Zn and ZnT3 accelerate brain aging of Rat. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 279, 505–511.

) or the increased expression of proteins such as MT (Mocchegiani et al., 2005Mocchegiani, E., Bertoni-Freddari, C., Marcellini, F., Malavolta, M. (2005) Brain, aging and neurodegeneration: role of zinc ion availability. Progress in Neurobiology 75, 367–390.

) that would bind to Zn2+. The enrichment in the light isotopes of Zn with age provides a new way to test the behaviour of Zn during aging. Since total Zn remains constant in the brain through normal aging (Rahil-Khazen et al., 2002Rahil-Khazen, R., Bolann, B.J., Myking, A., Ulvik, R.J. (2002) Multi-element analysis of trace element levels in human autopsy tissues by using inductively coupled atomic emission spectrometry technique (ICP-AES). Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology 16, 15–25.

), the changes in isotopic composition must be related to changes in Zn speciation in the brain. The bonding environment to be considered is that Zn is bound to cysteines in MT, histidines in ZnT and ZIP proteins, glutamates in pre-synaptic vesicles, and unbound hydrated Zn in the cytoplasm. If we consider a four-fold coordination, the logarithm of the reduced partition (lnβ) for the 66Zn/64Zn ratio decreases from Zn-histidine (lnβ ~3.7), Zn-glutamate and Zn(H2O)42+ (lnβ ~3.6), to Zn-cysteine (lnβ ~3.1) (Fujii et al., 2014Fujii, T., Moynier, F., Blichert-Toft, J., Albarede, F. (2014) Density functional theory estimation of isotope fractionation of Fe, Ni, Cu, and Zn among species relevant to geochemical and biological environments. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 140, 553–576.

). The lnβ can be directly compared to each other to estimate the variations in the δ66Zn, i.e. that δ66Zn(histidine) - δ66Zn(cysteine) = lnβ(histidine) - lnβ(cysteine) at ~0.6 ‰.The decrease of the δ66Zn with age suggests an increase of the Zn pool with the lightest isotopic composition. The behaviour of Zn isotopes is consistent with a decrease of isotopically heavy Zn2+. It is however inconsistent with the binding of free Zn2+ to glutamate-Zn (Saito et al., 2000

Saito, T., Takahashi, K., Nakagawa, N., Hosokawa, T., Kurasaki, M., Yamanoshita, O., Yamamoto, Y., Sasaki, H., Nagashima, K., Fujita, H. (2000) Deficiencies of hippocampal Zn and ZnT3 accelerate brain aging of Rat. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 279, 505–511.

) because both species have similar lnβ. Therefore, the depletion in Zn2+ is coupled with an increase in isotopically light Zn bound preferentially to proteins such as MT (Mocchegiani et al., 2005Mocchegiani, E., Bertoni-Freddari, C., Marcellini, F., Malavolta, M. (2005) Brain, aging and neurodegeneration: role of zinc ion availability. Progress in Neurobiology 75, 367–390.

).Contrary to the brains, the Zn isotopic composition of RBCs and serum does not change with age (Figs. 1 and 3). This suggests that δ66Zn of serum and RBCs could be used as tracers of changes in Zn metabolism with no need to correct for the age of the patients.

Effect of Alzheimer’s disease on the Zn isotopic composition of the brain. Alzheimer’s disease mice start to develop Aβ plaques from 6 months with abundant plaques in the hippocampus and cortex by 9 months (Jankowsky et al., 2004

Jankowsky, J.L., Fadale, D.J., Anderson, J., Xu, G.M., Gonzales, V., Jenkins, N.A., Copeland, N.G., Lee, M.K., Younkin, L.H., Wagner, S.L., Younkin, S.G., Borchelt, D.R. (2004) Mutant presenilins specifically elevate the levels of the 42 residue beta-amyloid peptide in vivo: evidence for augmentation of a 42-specific gamma secretase. Human Molecular Genetics 13, 159–170.

) and with increased plaque burden until 12 months (Garcia-Alloza et al., 2006Garcia-Alloza, M., Robbins, E.M., Zhang-Nunes, S.X., Purcell, S.M., Betensky, R.A., Raju, S., Prada, C., Greenberg, S.M., Bacskai, B.J., Frosch, M.P. (2006) Characterization of amyloid deposition in the APPswe/PS1dE9 mouse model of Alzheimer disease. Neurobiology of Disease 24, 516–524.

). Therefore the development of Aβ plaques in AD mice is coincident with the isotopic fractionation of Zn due to normal aging. While this result complicates the interpretations of the AD mice data, it is clear that there is an isotopic difference between the WT and the AD mice, with the latter heavier than the former in older mice (Fig. 3c). This enrichment in the heavier isotopes of Zn of AD mice is consistent with Aβ plaques enriched in the heavier isotopes of Zn compared to normal brain. Zinc is principally bound to histidine in Aβ (Faller and Hureau, 2009Faller, P., Hureau, C. (2009) Bioinorganic chemistry of copper and zinc ions coordinated to amyloid-beta peptide. Dalton Transactions, 1080–1094.

), which is isotopically heavier than Zn-MT (Moynier et al., 2013Moynier, F., Fujii, T., Shaw, A., Le Borgne, M. (2013) Heterogeneous distribution of natural zinc isotopes in mice. Metallomics 5, 693-699.

), the main Zn carrier in normal brains.The Zn concentration of brains was found to double in AD patients (Religa et al., 2006

Religa, D., Strozyk, D., Cherny, R.A., Volitakis, I., Haroutunian, V., Winblad, B., Naslund, J., Bush, A.I. (2006) Elevated cortical zinc in Alzheimer disease. Neurology 67, 69–75.

), in agreement with many studies that found enrichment of Zn in different brain regions such as hippocampus (Deibel et al., 1996Deibel, M.A., Ehmann, W.D., Markesbery, W.R. (1996) Copper, iron, and zinc imbalances in severely degenerated brain regions in Alzheimer's disease: possible relation to oxidative stress. Journal of the Neurological Sciences 143, 137–142.

), or amygdala (Deibel et al., 1996Deibel, M.A., Ehmann, W.D., Markesbery, W.R. (1996) Copper, iron, and zinc imbalances in severely degenerated brain regions in Alzheimer's disease: possible relation to oxidative stress. Journal of the Neurological Sciences 143, 137–142.

; Lovell et al., 1998Lovell, M.A., Robertson, J.D., Teesdale, W.J., Campbell, J.L., Markesbery, W.R. (1998) Copper, iron and zinc in Alzheimer's disease senile plaques. Journal of the Neurological Sciences 158, 47–52.

). Zinc in Aβ plaques is widely considered to bind to four ligands including three histidine residues in the N-terminal hydrophilic region Aβ16 of the Aβ peptide (Faller and Hureau, 2009Faller, P., Hureau, C. (2009) Bioinorganic chemistry of copper and zinc ions coordinated to amyloid-beta peptide. Dalton Transactions, 1080–1094.

; Pithadia and Lim, 2012Pithadia, A.S., Lim, M.H. (2012) Metal-associated amyloid-beta species in Alzheimer's disease. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology 16, 67–73.

), with a fourth possible binding site being either aspartate or glutamate (Faller and Hureau, 2009Faller, P., Hureau, C. (2009) Bioinorganic chemistry of copper and zinc ions coordinated to amyloid-beta peptide. Dalton Transactions, 1080–1094.

). While no ab initio calculations exist for aspartate, Zn bound to either the N-terminal amine or to O in the carboxylate function of aspartate (Faller and Hureau, 2009Faller, P., Hureau, C. (2009) Bioinorganic chemistry of copper and zinc ions coordinated to amyloid-beta peptide. Dalton Transactions, 1080–1094.

) should enrich the heavier isotopes of Zn (Moynier et al., 2013Moynier, F., Fujii, T., Shaw, A., Le Borgne, M. (2013) Heterogeneous distribution of natural zinc isotopes in mice. Metallomics 5, 693-699.

). Therefore, we can consider that Aβ δ66Zn is closer to histidine and glutamate. If we consider that 1) there is the same isotopic difference between Zn-Aβ and Zn-MT in normal brain as between Zn-histidine (or glutamate) and Zn-cysteine at ~0.6 ‰ and 2) that AD brain has twice as much Zn as normal brain, then AD brains are 0.3 ‰ heavier than normal brains, similar to our observations.Our study substantiates the potential of Zn isotopes as a tool to understand Zn homeostasis in living organisms. δ66Zn of brains change with time suggesting a change in the speciation of Zn, with a decrease in the unbound Zn2+ associated with an increase in Zn-MT. δ66Zn of the brain is altered in AD, with a progressive enrichment in the heavier isotopes of Zn associated with an increase in Aβ plaques. These results can be explained by an increase in Zn content of the brain associated with Aβ plaques where isotopically heavy Zn binds preferentially to histidine and glutamate.

top

Acknowledgements

FM thanks the Université Sorbonne Paris Cité for a chaire d'excellence and for support for the plateforme Isotopes. Parts of this work were supported by IPGP multidisciplinary PARI program, and by Region Île-de-France SESAME Grant no. 12015908.

Editor: Graham Pearson

top

References

Balter, V., Zazzo, A., Moloney, A.P., Moynier, F., Schmidt, O., Monahan, F.J., Albarede, F. (2010) Bodily variability of zinc natural isotope abundances in sheep. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry 24, 605–612.

Show in context

Show in context The stable isotopic composition of Zn naturally varies between body organs (Balter et al., 2010, 2013; Moynier et al., 2013; Jaouen et al., 2016).

View in article

In particular, RBCs are enriched by ~0.5 ‰ (for δ66Zn) when compared to serum, and up to ~1 ‰ when compared to the brain (Balter et al., 2010, 2013; Moynier et al., 2013).

View in article

Balter, V., Lamboux, A., Zazzo, A., Telouk, P., Leverrier, Y., Marvel, J., Moloney, A.P., Monahan, F.J., Schmidt, O., Albarede, F. (2013) Contrasting Cu, Fe, and Zn isotopic patterns in organs and body fluids of mice and sheep, with emphasis on cellular fractionation. Metallomics 5, 1470–1482.

Show in context

Show in context The stable isotopic composition of Zn naturally varies between body organs (Balter et al., 2010, 2013; Moynier et al., 2013; Jaouen et al., 2016).

View in article

In particular, RBCs are enriched by ~0.5 ‰ (for δ66Zn) when compared to serum, and up to ~1 ‰ when compared to the brain (Balter et al., 2010, 2013; Moynier et al., 2013).

View in article

Baum, L., Chan, I.H.S., Cheung, S.K.K., Goggins, W.B., Mok, V., Lam, L., Leung, V., Hui, E., Ng, C., Woo, J., Chiu, H.F.K., Zee, B.C.Y., Cheng, W., Chan, M.H., Szeto, S., Lui, V., Tsoh, J., Bush, A.I., Lam, C.W.K., Kwok, T. (2010) Serum zinc is decreased in Alzheimer's disease and serum arsenic correlates positively with cognitive ability. Biometals 23, 173–179.

Show in context

Show in context In addition, the homeostasis of metals, such as Zn, is dysregulated in AD patients (e.g., Baum et al., 2010; Szewczyk, 2013).

View in article

Following this approach, several studies have compared the Zn concentration in the serum of control and AD patients with inconsistent results (Baum et al., 2010).

View in article

Bertoni-Freddari, C., Fattoretti, P., Casoli, T., Di Stefano, G., Giorgetti, B., Balietti, M. (2008) Brain aging: The zinc connection. Experimental Gerontology 43, 389–393.

Show in context

Show in context It is well known that aging brains display several changes, such as a decrease of the number of neurons as well as a decline in the cell-to-cell communications due to a deterioration of the synaptic contact zone (Casoli et al., 1996; Bertoni-Freddari et al., 2008).

View in article

The exact behaviour and role of Zn during normal brain aging is still unclear: some studies showed that unbound Zn2+ increases (Bertoni-Freddari et al., 2008) whereas other studies suggest that it decreases (Mocchegiani et al., 2005).

View in article

Casoli, T., Spagna, C., Fattoretti, P., Gesuita, R., Bertoni-Freddari, C. (1996) Neuronal plasticity in aging: a quantitative immunohistochemical study of GAP-43 distribution in discrete regions of the rat brain. Brain Research 714, 111–117.

Show in context

Show in context It is well known that aging brains display several changes, such as a decrease of the number of neurons as well as a decline in the cell-to-cell communications due to a deterioration of the synaptic contact zone (Casoli et al., 1996; Bertoni-Freddari et al., 2008).

View in article

Deibel, M.A., Ehmann, W.D., Markesbery, W.R. (1996) Copper, iron, and zinc imbalances in severely degenerated brain regions in Alzheimer's disease: possible relation to oxidative stress. Journal of the Neurological Sciences 143, 137–142.

Show in context

Show in context The Zn concentration of brains was found to double in AD patients (Religa et al., 2006), in agreement with many studies that found enrichment of Zn in different brain regions such as hippocampus (Deibel et al., 1996), or amygdala (Deibel et al., 1996; Lovell et al., 1998).

View in article

Faller, P., Hureau, C. (2009) Bioinorganic chemistry of copper and zinc ions coordinated to amyloid-beta peptide. Dalton Transactions, 1080–1094.

Show in context

Show in context For example, Zn is principally bound to histidine in amyloid-beta that are formed during the AD (Faller and Hureau, 2009), which should enrich the AD brains in isotopically heavy Zn compared to controls and possibly deplete the serum in the lighter isotopes.

View in article

Zinc is principally bound to histidine in Aβ (Faller and Hureau, 2009), which is isotopically heavier than Zn-MT (Moynier et al., 2013), the main Zn carrier in normal brains.

View in article

Zinc in Aβ plaques is widely considered to bind to four ligands including three histidine residues in the N-terminal hydrophilic region Aβ16 of the Aβ peptide (Faller and Hureau, 2009; Pithadia and Lim, 2012), with a fourth possible binding site being either aspartate or glutamate (Faller and Hureau, 2009).

View in article

While no ab initio calculations exist for aspartate, Zn bound to either the N-terminal amine or to O in the carboxylate function of aspartate (Faller and Hureau, 2009) should enrich the heavier isotopes of Zn (Moynier et al., 2013).

View in article

Frederickson, C.J. (1989) Neurobiology of zinc and zinc-containing neurons. International Review of Neurobiology 31, 145–238.

Show in context

Show in context In the brain, Zn is mostly distributed within three reservoirs in three different species (Szewczyk, 2013): 1) sequestered in the presynaptic vesicles of neurons co-located with glutamate (Frederickson, 1989; Frederickson et al., 2000); 2) bound to intra-cellular proteins such as metallothioneins (MT) (Krezel et al., 2007), ZIP and membranous transporter proteins (ZnT) (Huang and Tepaamorndech, 2013); and 3) unbound ions in the cytoplasm as hydrated Zn2+ (Frederickson et al., 2000).

View in article

Frederickson, C.J., Suh, S.W., Silva, D., Frederickson, C.J., Thompson, R.B. (2000) Importance of zinc in the central nervous system: the zinc-containing neuron. Journal of Nutrition 130, 1471S–1483S.

Show in context

Show in context In the brain, Zn is mostly distributed within three reservoirs in three different species (Szewczyk, 2013): 1) sequestered in the presynaptic vesicles of neurons co-located with glutamate (Frederickson, 1989; Frederickson et al., 2000); 2) bound to intra-cellular proteins such as metallothioneins (MT) (Krezel et al., 2007), ZIP and membranous transporter proteins (ZnT) (Huang and Tepaamorndech, 2013); and 3) unbound ions in the cytoplasm as hydrated Zn2+ (Frederickson et al., 2000).

View in article

Fujii, T., Moynier, F., Blichert-Toft, J., Albarede, F. (2014) Density functional theory estimation of isotope fractionation of Fe, Ni, Cu, and Zn among species relevant to geochemical and biological environments. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 140, 553–576.

Show in context

Show in context If we consider a four-fold coordination, the logarithm of the reduced partition (lnβ) for the 66Zn/64Zn ratio decreases from Zn-histidine (lnβ ~3.7), Zn-glutamate and Zn(H2O)42+ (lnβ ~3.6), to Zn-cysteine (lnβ ~3.1) (Fujii et al., 2014).

View in article

Garcia-Alloza, M., Robbins, E.M., Zhang-Nunes, S.X., Purcell, S.M., Betensky, R.A., Raju, S., Prada, C., Greenberg, S.M., Bacskai, B.J., Frosch, M.P. (2006) Characterization of amyloid deposition in the APPswe/PS1dE9 mouse model of Alzheimer disease. Neurobiology of Disease 24, 516–524.

Show in context

Show in context We present the Zn isotopic composition of transgenic APPswe/PSEN1dE9 and wild type (WT) controls for which we have collected the brain, RBCs and serum at the early stage (6 months) and late stage of AD (9 and 12 months) (Jankowsky et al., 2004; Garcia-Alloza et al., 2006) to assess how AD affects the balance of zinc isotopes in the brain.

View in article

Alzheimer’s disease mice start to develop Aβ plaques from 6 months with abundant plaques in the hippocampus and cortex by 9 months (Jankowsky et al., 2004) and with increased plaque burden until 12 months (Garcia-Alloza et al., 2006).

View in article

GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators (2015) Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 385, 117–171.

Show in context

Show in context Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common type of dementia and one of the main causes of death in high-income countries (GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators, 2015).

View in article

Huang, L., Tepaamorndech, S. (2013) The SLC30 family of zinc transporters - a review of current understanding of their biological and pathophysiological roles. Molecular Aspects of Medicine 34, 548–560.

Show in context

Show in context In the brain, Zn is mostly distributed within three reservoirs in three different species (Szewczyk, 2013): 1) sequestered in the presynaptic vesicles of neurons co-located with glutamate (Frederickson, 1989; Frederickson et al., 2000); 2) bound to intra-cellular proteins such as metallothioneins (MT) (Krezel et al., 2007), ZIP and membranous transporter proteins (ZnT) (Huang and Tepaamorndech, 2013); and 3) unbound ions in the cytoplasm as hydrated Zn2+ (Frederickson et al., 2000).

View in article

Jankowsky, J.L., Fadale, D.J., Anderson, J., Xu, G.M., Gonzales, V., Jenkins, N.A., Copeland, N.G., Lee, M.K., Younkin, L.H., Wagner, S.L., Younkin, S.G., Borchelt, D.R. (2004) Mutant presenilins specifically elevate the levels of the 42 residue beta-amyloid peptide in vivo: evidence for augmentation of a 42-specific gamma secretase. Human Molecular Genetics 13, 159–170.

Show in context

Show in context We present the Zn isotopic composition of transgenic APPswe/PSEN1dE9 and wild type (WT) controls for which we have collected the brain, RBCs and serum at the early stage (6 months) and late stage of AD (9 and 12 months) (Jankowsky et al., 2004; Garcia-Alloza et al., 2006) to assess how AD affects the balance of zinc isotopes in the brain.

View in article

Alzheimer’s disease mice start to develop Aβ plaques from 6 months with abundant plaques in the hippocampus and cortex by 9 months (Jankowsky et al., 2004) and with increased plaque burden until 12 months (Garcia-Alloza et al., 2006).

View in article

Jaouen, K., Beasley, M., Schoeninger, M., Hublin, J., Richards, M. (2016) Zinc isotope ratios of bones and teeth as new dietary indicators: results from a modern food web (Koobi Fora, Kenya). Scientific Reports 6, 26281.

Show in context

Show in context The stable isotopic composition of Zn naturally varies between body organs (Balter et al., 2010, 2013; Moynier et al., 2013; Jaouen et al., 2016).

View in article

Krezel, A., Hao, Q., Maret, W. (2007) The zinc/thiolate redox biochemistry of metallothionein and the control of zinc ion fluctuations in cell signaling. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 463, 188–200.

Show in context

Show in context In the brain, Zn is mostly distributed within three reservoirs in three different species (Szewczyk, 2013): 1) sequestered in the presynaptic vesicles of neurons co-located with glutamate (Frederickson, 1989; Frederickson et al., 2000); 2) bound to intra-cellular proteins such as metallothioneins (MT) (Krezel et al., 2007), ZIP and membranous transporter proteins (ZnT) (Huang and Tepaamorndech, 2013); and 3) unbound ions in the cytoplasm as hydrated Zn2+ (Frederickson et al., 2000).

View in article

Lovell, M.A., Robertson, J.D., Teesdale, W.J., Campbell, J.L., Markesbery, W.R. (1998) Copper, iron and zinc in Alzheimer's disease senile plaques. Journal of the Neurological Sciences 158, 47–52.

Show in context

Show in context The Zn concentration of brains was found to double in AD patients (Religa et al., 2006), in agreement with many studies that found enrichment of Zn in different brain regions such as hippocampus (Deibel et al., 1996), or amygdala (Deibel et al., 1996; Lovell et al., 1998).

View in article

Miller, L.M., Wang, Q., Telivala, T.P., Smith, R.J., Lanzirotti, A., Miklossy, J. (2006) Synchrotron-based infrared and X-ray imaging shows focalized accumulation of Cu and Zn co-localized with beta-amyloid deposits in Alzheimer's disease. Journal of Structural Biology 155, 30–37.

Show in context

Show in context While the full role of Zn in AD is not totally clear yet, there is much evidence that Zn is involved in the formation of Aβ leading to an enrichment of Zn in the neocortex of AD patients (e.g., Miller et al., 2006; Religa et al., 2006).

View in article

Mocchegiani, E., Bertoni-Freddari, C., Marcellini, F., Malavolta, M. (2005) Brain, aging and neurodegeneration: role of zinc ion availability. Progress in Neurobiology 75, 367–390.

Show in context

Show in context The exact behaviour and role of Zn during normal brain aging is still unclear: some studies showed that unbound Zn2+ increases (Bertoni-Freddari et al., 2008) whereas other studies suggest that it decreases (Mocchegiani et al., 2005).

View in article

Possible explanations for the decrease of free Zn would be the excessive pre-synaptic release of glutamate (Saito et al., 2000) or the increased expression of proteins such as MT (Mocchegiani et al., 2005) that would bind to Zn2+.

View in article

Therefore, the depletion in Zn2+ is coupled with an increase in isotopically light Zn bound preferentially to proteins such as MT (Mocchegiani et al., 2005).

View in article

Moynier, F., Fujii, T., Shaw, A., Le Borgne, M. (2013) Heterogeneous distribution of natural zinc isotopes in mice. Metallomics 5, 693-699.

Show in context

Show in context The stable isotopic composition of Zn naturally varies between body organs (Balter et al., 2010, 2013; Moynier et al., 2013; Jaouen et al., 2016).

View in article

In particular, RBCs are enriched by ~0.5 ‰ (for δ66Zn) when compared to serum, and up to ~1 ‰ when compared to the brain (Balter et al., 2010, 2013; Moynier et al., 2013).

View in article

Differences in isotope ratio were not altered by gender, genetic background or age (up to 16 weeks) in multiple organs of mice (Moynier et al., 2013).

View in article

This difference between organs is explained by isotope fractionation at equilibrium between different bonding environments of Zn where isotopically light Zn is enriched in cysteine-rich proteins in the brain (metallothionein) and isotopically heavy Zn enriched in histidine-rich proteins in RBCs (carbonic anhydrase) (Moynier et al., 2013).

View in article

All the mice were fed the same diet (water and dry food) from birth and were housed in the same animal facility as our previous study (Moynier et al., 2013); we can therefore directly compare the isotopic composition of the two studies.

View in article

These results are in excellent agreement with what we previously reported (Moynier et al., 2013).

View in article

The youngest mice that we analysed in this study are 6 months old, and have Zn isotopic composition of the brains (0.05 ± 0.07 ‰; n = 5) identical to the mice measured in previous studies (-0.03 ± 0.08 ‰; n = 14, Moynier et al., 2013).

View in article

Zinc is principally bound to histidine in Aβ (Faller and Hureau, 2009), which is isotopically heavier than Zn-MT (Moynier et al., 2013), the main Zn carrier in normal brains.

View in article

While no ab initio calculations exist for aspartate, Zn bound to either the N-terminal amine or to O in the carboxylate function of aspartate (Faller and Hureau, 2009) should enrich the heavier isotopes of Zn (Moynier et al., 2013).

View in article

Moynier, F., Vance, D., Fujii, T., Savage, P. (2017) The isotope geochemistry of zinc and copper. Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry 82, 543–600.

Show in context

Show in context The reference material used is the Zn “Lyon” standard JMC 3-0749 L (e.g., see Moynier et al., 2017 for review).

View in article

Pithadia, A.S., Lim, M.H. (2012) Metal-associated amyloid-beta species in Alzheimer's disease. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology 16, 67–73.

Show in context

Show in context Zinc in Aβ plaques is widely considered to bind to four ligands including three histidine residues in the N-terminal hydrophilic region Aβ16 of the Aβ peptide (Faller and Hureau, 2009; Pithadia and Lim, 2012), with a fourth possible binding site being either aspartate or glutamate (Faller and Hureau, 2009).

View in article

Rahil-Khazen, R., Bolann, B.J., Myking, A., Ulvik, R.J. (2002) Multi-element analysis of trace element levels in human autopsy tissues by using inductively coupled atomic emission spectrometry technique (ICP-AES). Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology 16, 15–25.

Show in context

Show in context Since total Zn remains constant in the brain through normal aging (Rahil-Khazen et al., 2002), the changes in isotopic composition must be related to changes in Zn speciation in the brain.

View in article

Religa, D., Strozyk, D., Cherny, R.A., Volitakis, I., Haroutunian, V., Winblad, B., Naslund, J., Bush, A.I. (2006) Elevated cortical zinc in Alzheimer disease. Neurology 67, 69–75.

Show in context

Show in context While the full role of Zn in AD is not totally clear yet, there is much evidence that Zn is involved in the formation of Aβ leading to an enrichment of Zn in the neocortex of AD patients (e.g., Miller et al., 2006; Religa et al., 2006).

View in article

The Zn concentration of brains was found to double in AD patients (Religa et al., 2006), in agreement with many studies that found enrichment of Zn in different brain regions such as hippocampus (Deibel et al., 1996), or amygdala (Deibel et al., 1996; Lovell et al., 1998).

View in article

Saito, T., Takahashi, K., Nakagawa, N., Hosokawa, T., Kurasaki, M., Yamanoshita, O., Yamamoto, Y., Sasaki, H., Nagashima, K., Fujita, H. (2000) Deficiencies of hippocampal Zn and ZnT3 accelerate brain aging of Rat. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 279, 505–511.

Show in context

Show in context Possible explanations for the decrease of free Zn would be the excessive pre-synaptic release of glutamate (Saito et al., 2000) or the increased expression of proteins such as MT (Mocchegiani et al., 2005) that would bind to Zn2+.

View in article

It is however inconsistent with the binding of free Zn2+ to glutamate-Zn (Saito et al., 2000) because both species have similar lnβ.

View in article

Szewczyk, B. (2013) Zinc homeostasis and neurodegenerative disorders. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 5, 12.

Show in context

Show in context In addition, the homeostasis of metals, such as Zn, is dysregulated in AD patients (e.g., Baum et al., 2010; Szewczyk, 2013).

View in article

In the brain, Zn is mostly distributed within three reservoirs in three different species (Szewczyk, 2013): 1) sequestered in the presynaptic vesicles of neurons co-located with glutamate (Frederickson, 1989; Frederickson et al., 2000); 2) bound to intra-cellular proteins such as metallothioneins (MT) (Krezel et al., 2007), ZIP and membranous transporter proteins (ZnT) (Huang and Tepaamorndech, 2013); and 3) unbound ions in the cytoplasm as hydrated Zn2+ (Frederickson et al., 2000).

View in article

Vasto, S., Mocchegiani, E., Malavolta, M., Cuppari, I., Listì, F., Nuzzo, D., Ditta, V., Candore, G., Caruso, C. (2007) Zinc and inflammatory/immune response in aging. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 100, 111–122.

Show in context

Show in context Elemental abundance variations in the serum may be subjected to many factors unrelated to AD, such as intestinal absorption of Zn (Vasto et al., 2007), which potentially explain the result inconsistencies.

View in article

top

Supplementary Information

Material and Methods

Ethics statement

Care and use of mice were conducted in accordance with protocols approved by the Washington University Animal Studies Committee (ASC), in compliance with the Animal Welfare Act. All mice were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions in the Washington University animal facilities.

Mice

We started the study with 60 mice. Thirty APPswe/PSEN1dE9 (AD) (15 males and 15 females), and 30 wild type (WT) littermate controls (15 males and 15 females) on a C57BL/6 and C3H mixed background. At 6, 9 and 12 months, blood and brain from 10 AD mice and 10 WT mice were collected. For the 12-month-old group, blood was collected every three months until their death. All mice were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions in the Washington University animal facilities in accordance with institutional guidelines, and were given the same diet from birth. The diet is similar as the one reported in Moynier et al. (2013). AD mice were originally obtained from The Jackson Laboratory, then bred and housed in the Washington University animal facilities by crossing to B3C3F1/J (from The Jackson Laboratory).

Sample collection

Samples were collected as described previously (Moynier et al., 2013). Briefly, blood was collected in polypropylene microtubes and serum and red blood cells (RBC) were separated by centrifugation. After blood collection, mice were perfused by injecting phosphate buffered saline (PBS) through the heart with a dissected hepatic vein to remove blood from organs. Brains were harvested using instruments of stainless steel. All samples were stored in polypropylene microtubes or cryogenic vials (Corning). Harvested organs were snap-frozen and kept frozen until dissolution. Zinc contamination from the PBS (<20 ng) was negligible in comparison to the amount of Zn present in the organs (>5 μg). Due to some contamination when the samples were collected, only five 12-month-old WT and five 12-month-old AD brains were analysed. Also, as we observed only minor differences for the 9-month-old mice, we only analysed the zinc isotopic composition of five WT and seven AD 6-month-old brains.

Chemical purification and mass spectrometry

The method used to measure the Zn isotopic composition of mice organs was described in Moynier and Le Borgne (2015) which is similar to our previous study of mice organs (Moynier et al., 2013). All the brains were first cleaned twice using 18.2 MW cm water and the brain, RBCs and serum were dissolved using a mixture of HNO3 (4 times sub-boiled) and Seastar© optima grade H2O2 in closed Teflon beakers for one to two days. This method provides a complete dissolution of the organs with minimum contamination (as opposed to the combustion of the organs in an oven).

Prior to MC-ICP-MS analysis, Zn was purified by ion exchange chromatography following procedures described previously (Moynier and Le Borgne, 2015), such that elements both producing interferences on the masses of the Zn isotopes, and acting to degrade the stability of the instrument by inducing matrix effects, were removed. The samples were loaded in 1.5N HBr on 0.25 ml AG-1X8 (200–400 mesh) ion-exchange columns and Zn was eluted in 0.5N HNO3. The Zn fraction was further purified by eluting the samples on a 100 μl column following the same method.

Zinc isotopic data were measured using the MC-ICP-MS (Thermo-Finnigan Neptune Plus) at the Isotope Geochemistry Laboratory at Washington University in St Louis. A 0.5 ppm solution of purified Zn sample was introduced into the mass spectrometer using a spray chamber inlet system and a 100 μL/min PFA nebuliser. The measurements were made in low-resolution mode following the procedures previously described (Moynier and Le Borgne, 2015). The sample dilutions were adjusted (to within ~±5 %) to match the concentration of the standard.

The total yield of Zn was >99 %. The blank of the full procedure is <10 ng which is negligible in comparison to the amount of Zn present in each samples (>1 μg). Replicate analyses of the same samples carried out during different analytical sessions define our external reproducibility of ± 0.04 ‰ (2σ) for δ66Zn and 0.05 ‰ for δ68Zn (Chen et al., 2013).

The isotopic composition of Zn is reported as parts per 1,000 deviations relative to a standard:

where x = 66 or 68. The reference material used is the Zn “Lyon” standard JMC 3-0749 L (e.g., see Moynier et al., 2017 for review).

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism. Data are represented as box-and-whiskers graphs, with the box always extending from the 25th to 75th percentiles, the line representing the median, and the whiskers showing the minimal and maximal values. We performed two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (McDonald, 1999). When two-way ANOVA tests showed significant effects, multiple comparison tests (Sidak’s tests) were performed to compare the means of selected groups.

Table S-1 Zinc isotopic composition of the different samples analysed in this study.

| Mouse | Genotype | Sex | Age | Brain | Serum | RBC 9 months | RBC 12 months | ||||

| (months) | δ66Zn | δ68Zn | δ66Zn | δ68Zn | δ66Zn | δ68Zn | δ66Zn | δ68Zn | |||

| 10 | WT | female | 12 | 0.41 | 0.91 | 1.02 | 2.01 | 1.05 | 2.06 | ||

| 13 | WT | female | 12 | 0.63 | 1.35 | 0.99 | 1.90 | 1.09 | 2.18 | ||

| 14 | WT | female | 12 | 0.48 | 1.05 | 0.95 | 1.84 | 0.95 | 1.87 | ||

| 16 | WT | female | 12 | 0.49 | 1.11 | 0.95 | 1.86 | 0.99 | 1.91 | ||

| 29 | WT | female | 12 | 0.33 | 0.74 | ||||||

| 2 | WT | male | 12 | -0.75 | -1.42 | 0.90 | 1.77 | 0.86 | 1.72 | ||

| 4 | WT | male | 12 | -0.37 | -0.66 | 0.42 | 1.02 | 0.93 | 1.81 | 0.87 | 1.74 |

| 21 | WT | male | 12 | -0.90 | -1.74 | 0.57 | 1.27 | 1.01 | 1.96 | 0.92 | 1.82 |

| 24 | WT | male | 12 | -0.27 | -0.52 | 0.63 | 1.42 | 0.97 | 1.87 | ||

| 26 | WT | male | 12 | -0.34 | -0.71 | 1.06 | 2.10 | ||||

| 9 | AD | female | 12 | 0.43 | 0.99 | 0.94 | 1.83 | 1.02 | 1.99 | ||

| 11 | AD | female | 12 | 0.30 | 0.71 | 0.98 | 1.89 | 0.77 | 1.51 | ||

| 12 | AD | female | 12 | 0.40 | 1.02 | 0.88 | 1.77 | ||||

| 15 | AD | female | 12 | 0.67 | 1.46 | 1.09 | 2.11 | 0.94 | 1.86 | ||

| 17 | AD | female | 12 | 0.55 | 1.19 | 1.00 | 1.96 | 0.97 | 1.90 | ||

| 31 | AD | female | 12 | 0.55 | 1.32 | 1.06 | 2.10 | 0.96 | 1.91 | ||

| 1 | AD | male | 12 | -0.08 | -0.13 | 0.74 | 1.57 | 0.99 | 1.94 | 0.96 | 1.91 |

| 3 | AD | male | 12 | -0.12 | -0.25 | 0.61 | 1.28 | 0.99 | 1.94 | 0.92 | 1.81 |

| 5 | AD | male | 12 | -0.42 | -0.83 | 0.72 | 1.50 | 0.98 | 1.94 | 0.97 | 1.94 |

| 6 | AD | male | 12 | 0.94 | 1.85 | 1.12 | 2.22 | ||||

| 7 | AD | male | 12 | 0.60 | 1.30 | 1.05 | 2.03 | 1.10 | 2.14 | ||

| 20 | AD | male | 12 | -0.30 | -0.57 | 0.64 | 1.37 | 1.10 | 2.14 | 0.97 | 1.93 |

| 25 | AD | male | 12 | -0.17 | -0.31 | 0.61 | 1.33 | 1.05 | 2.01 | 0.92 | 1.88 |

| 30 | WT | female | 9 | -0.08 | -0.11 | ||||||

| 32 | WT | female | 9 | -0.08 | -0.13 | 0.92 | 1.83 | ||||

| 45 | WT | female | 9 | -0.11 | -0.22 | 1.03 | 1.99 | ||||

| 57 | WT | female | 9 | -0.15 | -0.28 | 0.55 | 1.35 | 0.96 | 1.88 | ||

| 58 | WT | female | 9 | -0.08 | -0.16 | 0.55 | 1.36 | 1.02 | 2.02 | ||

| 38 | WT | male | 9 | -0.07 | -0.11 | 0.88 | 1.76 | ||||

| 41 | WT | male | 9 | -0.26 | -0.52 | 0.46 | 1.12 | 0.98 | 1.97 | ||

| 42 | WT | male | 9 | -0.32 | -0.62 | 0.45 | 1.14 | 0.94 | 1.87 | ||

| 51 | WT | male | 9 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.78 | 1.59 | 1.09 | 2.15 | ||

| 35 | AD | female | 9 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.87 | 1.72 | ||||

| 36 | AD | female | 9 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 1.03 | 2.08 | ||||

| 37 | AD | female | 9 | -0.01 | 0.00 | ||||||

| 46 | AD | female | 9 | -0.20 | -0.36 | 0.53 | 1.26 | 1.03 | 2.00 | ||

| 49 | AD | female | 9 | -0.37 | -0.71 | 0.91 | 1.80 | ||||

| 39 | AD | male | 9 | 0.07 | 0.16 | 0.93 | 1.85 | ||||

| 40 | AD | male | 9 | -0.01 | -0.01 | 1.01 | 1.96 | ||||

| 43 | AD | male | 9 | 0.12 | 0.26 | 0.64 | 1.49 | 0.96 | 1.89 | ||

| 44 | AD | male | 9 | 0.00 | -0.01 | 0.58 | 1.33 | ||||

| 52 | AD | male | 9 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.74 | 1.69 | 1.11 | 2.21 | ||

| 53 | AD | male | 9 | -0.03 | -0.03 | 0.99 | 1.95 | ||||

| 84 | WT | female | 6 | -0.03 | -0.04 | ||||||

| 85 | WT | female | 6 | 0.04 | 0.06 | ||||||

| 73 | WT | male | 6 | 0.12 | 0.22 | ||||||

| 80 | WT | male | 6 | -0.01 | -0.01 | ||||||

| 88 | WT | male | 6 | 0.11 | 0.22 | ||||||

| 72 | AD | female | 6 | -0.09 | -0.16 | ||||||

| 81 | AD | female | 6 | -0.04 | -0.01 | ||||||

| 82 | AD | female | 6 | -0.14 | -0.24 | ||||||

| 75 | AD | male | 6 | 0.02 | 0.03 | ||||||

| 77 | AD | male | 6 | 0.05 | 0.10 | ||||||

| 87 | AD | male | 6 | -0.01 | 0.02 | ||||||

| 89 | AD | male | 6 | 0.15 | 0.30 | | | | |||

Table S-2 Average isotopic composition of brain, RBC, and serum samples measured in this study.

| Brain | Brain | Brain | Serum | Serum | RBC | RBC | ||

| 12 months | 9 months | 6 months | 12 months | 9 months | 12 months | 9 months | ||

| Wild type | δ66Zn | -0.53 | -0.12 | 0.05 | 0.5 | 0.56 | 0.97 | 0.97 |

| SD | 0.28 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.08 | 0.06 | |

| n | 5 | 9 | 5 | 8 | 5 | 9 | 15 | |

| APPswe/PSEN1dE9 | δ66Zn | -0.22 | -0.03 | -0.01 | 0.57 | 0.62 | 0.96 | 1 |

| SD | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.1 | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.07 | |

| n | 5 | 11 | 7 | 12 | 4 | 13 | 20 |

Supplementary Information References

McDonald, J.H. (1999) Handbook of biological statistics. Sparky house publishing, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Moynier, F., Fujii, T., Shaw, A., Le Borgne, M. (2013) Heterogeneous distribution of natural zinc isotopes in mice. Metallomics 5, 693–699.

Moynier, F., Le Borgne, M. (2015) High precision zinc isotopic measurements applied to mouse organs. Journal of Visualized Experiments, e52479.

Moynier, F., Vance, D., Fujii, T., Savage, P. (2017) The isotope geochemistry of zinc and copper. Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry 82, 543–600.

Figures and Tables

Figure 1 δ66Zn of brains, serum and RBCs of WT mice over time. Boxes extend from the 25th and 75th percentile, the line in the middle of the box represents the median, and the whiskers show the minimum and the maximum. Two-way ANOVA was performed to compare groups (F value: 11.95, p < 0.0001), followed by Sidak’s multiple comparison test to compare the means between organs for each time point (*** indicates statistical difference, p < 0.001).

Figure 2 Effect of the sex on δ66Zn. Data show pooled results from 9- and 12-month-old WT mice for (a) RBCs and (b) serum, and (c) 6- and 9-month-old WT mice for brain. Student’s t-test showed no significant differences in any organ between males and females.

Figure 3 Effect of Alzheimer’s disease on δ66Zn. Data show results from WT and AD mice for (a) RBCs, (b) serum and (c) brain. Two-way ANOVA showed no significant effect of age or genotype for RBCs (F = 1.953, p = 0.17; a) or serum (F = 0.008, p = 0.92; b), and showed significant effect of age and genotype (F = 4.288, p = 0.0214) for brain (c). Sidak’s multiple comparison tests were run to compare groups for brain samples: asterisks indicate significant difference between groups (*: p < 0.05; **: p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001).

Back to article

Supplementary Figures and Tables

Table S-1 Zinc isotopic composition of the different samples analysed in this study.

| Mouse | Genotype | Sex | Age | Brain | Serum | RBC 9 months | RBC 12 months | ||||

| (months) | δ66Zn | δ68Zn | δ66Zn | δ68Zn | δ66Zn | δ68Zn | δ66Zn | δ68Zn | |||

| 10 | WT | female | 12 | 0.41 | 0.91 | 1.02 | 2.01 | 1.05 | 2.06 | ||

| 13 | WT | female | 12 | 0.63 | 1.35 | 0.99 | 1.90 | 1.09 | 2.18 | ||

| 14 | WT | female | 12 | 0.48 | 1.05 | 0.95 | 1.84 | 0.95 | 1.87 | ||

| 16 | WT | female | 12 | 0.49 | 1.11 | 0.95 | 1.86 | 0.99 | 1.91 | ||

| 29 | WT | female | 12 | 0.33 | 0.74 | ||||||

| 2 | WT | male | 12 | -0.75 | -1.42 | 0.90 | 1.77 | 0.86 | 1.72 | ||

| 4 | WT | male | 12 | -0.37 | -0.66 | 0.42 | 1.02 | 0.93 | 1.81 | 0.87 | 1.74 |

| 21 | WT | male | 12 | -0.90 | -1.74 | 0.57 | 1.27 | 1.01 | 1.96 | 0.92 | 1.82 |

| 24 | WT | male | 12 | -0.27 | -0.52 | 0.63 | 1.42 | 0.97 | 1.87 | ||

| 26 | WT | male | 12 | -0.34 | -0.71 | 1.06 | 2.10 | ||||

| 9 | AD | female | 12 | 0.43 | 0.99 | 0.94 | 1.83 | 1.02 | 1.99 | ||

| 11 | AD | female | 12 | 0.30 | 0.71 | 0.98 | 1.89 | 0.77 | 1.51 | ||

| 12 | AD | female | 12 | 0.40 | 1.02 | 0.88 | 1.77 | ||||

| 15 | AD | female | 12 | 0.67 | 1.46 | 1.09 | 2.11 | 0.94 | 1.86 | ||

| 17 | AD | female | 12 | 0.55 | 1.19 | 1.00 | 1.96 | 0.97 | 1.90 | ||

| 31 | AD | female | 12 | 0.55 | 1.32 | 1.06 | 2.10 | 0.96 | 1.91 | ||

| 1 | AD | male | 12 | -0.08 | -0.13 | 0.74 | 1.57 | 0.99 | 1.94 | 0.96 | 1.91 |

| 3 | AD | male | 12 | -0.12 | -0.25 | 0.61 | 1.28 | 0.99 | 1.94 | 0.92 | 1.81 |

| 5 | AD | male | 12 | -0.42 | -0.83 | 0.72 | 1.50 | 0.98 | 1.94 | 0.97 | 1.94 |

| 6 | AD | male | 12 | 0.94 | 1.85 | 1.12 | 2.22 | ||||

| 7 | AD | male | 12 | 0.60 | 1.30 | 1.05 | 2.03 | 1.10 | 2.14 | ||

| 20 | AD | male | 12 | -0.30 | -0.57 | 0.64 | 1.37 | 1.10 | 2.14 | 0.97 | 1.93 |

| 25 | AD | male | 12 | -0.17 | -0.31 | 0.61 | 1.33 | 1.05 | 2.01 | 0.92 | 1.88 |

| 30 | WT | female | 9 | -0.08 | -0.11 | ||||||

| 32 | WT | female | 9 | -0.08 | -0.13 | 0.92 | 1.83 | ||||

| 45 | WT | female | 9 | -0.11 | -0.22 | 1.03 | 1.99 | ||||

| 57 | WT | female | 9 | -0.15 | -0.28 | 0.55 | 1.35 | 0.96 | 1.88 | ||

| 58 | WT | female | 9 | -0.08 | -0.16 | 0.55 | 1.36 | 1.02 | 2.02 | ||

| 38 | WT | male | 9 | -0.07 | -0.11 | 0.88 | 1.76 | ||||

| 41 | WT | male | 9 | -0.26 | -0.52 | 0.46 | 1.12 | 0.98 | 1.97 | ||

| 42 | WT | male | 9 | -0.32 | -0.62 | 0.45 | 1.14 | 0.94 | 1.87 | ||

| 51 | WT | male | 9 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.78 | 1.59 | 1.09 | 2.15 | ||

| 35 | AD | female | 9 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.87 | 1.72 | ||||

| 36 | AD | female | 9 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 1.03 | 2.08 | ||||

| 37 | AD | female | 9 | -0.01 | 0.00 | ||||||

| 46 | AD | female | 9 | -0.20 | -0.36 | 0.53 | 1.26 | 1.03 | 2.00 | ||

| 49 | AD | female | 9 | -0.37 | -0.71 | 0.91 | 1.80 | ||||

| 39 | AD | male | 9 | 0.07 | 0.16 | 0.93 | 1.85 | ||||

| 40 | AD | male | 9 | -0.01 | -0.01 | 1.01 | 1.96 | ||||

| 43 | AD | male | 9 | 0.12 | 0.26 | 0.64 | 1.49 | 0.96 | 1.89 | ||

| 44 | AD | male | 9 | 0.00 | -0.01 | 0.58 | 1.33 | ||||

| 52 | AD | male | 9 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.74 | 1.69 | 1.11 | 2.21 | ||

| 53 | AD | male | 9 | -0.03 | -0.03 | 0.99 | 1.95 | ||||

| 84 | WT | female | 6 | -0.03 | -0.04 | ||||||

| 85 | WT | female | 6 | 0.04 | 0.06 | ||||||

| 73 | WT | male | 6 | 0.12 | 0.22 | ||||||

| 80 | WT | male | 6 | -0.01 | -0.01 | ||||||

| 88 | WT | male | 6 | 0.11 | 0.22 | ||||||

| 72 | AD | female | 6 | -0.09 | -0.16 | ||||||

| 81 | AD | female | 6 | -0.04 | -0.01 | ||||||

| 82 | AD | female | 6 | -0.14 | -0.24 | ||||||

| 75 | AD | male | 6 | 0.02 | 0.03 | ||||||

| 77 | AD | male | 6 | 0.05 | 0.10 | ||||||

| 87 | AD | male | 6 | -0.01 | 0.02 | ||||||

| 89 | AD | male | 6 | 0.15 | 0.30 | ||||||

Table S-2 Average isotopic composition of brain, RBC, and serum samples measured in this study.

| Brain | Brain | Brain | Serum | Serum | RBC | RBC | ||

| 12 months | 9 months | 6 months | 12 months | 9 months | 12 months | 9 months | ||

| Wild type | δ66Zn | -0.53 | -0.12 | 0.05 | 0.5 | 0.56 | 0.97 | 0.97 |

| SD | 0.28 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.08 | 0.06 | |

| n | 5 | 9 | 5 | 8 | 5 | 9 | 15 | |

| APPswe/PSEN1dE9 | δ66Zn | -0.22 | -0.03 | -0.01 | 0.57 | 0.62 | 0.96 | 1 |

| SD | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.1 | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.07 | |

| n | 5 | 11 | 7 | 12 | 4 | 13 | 20 |