No direct contribution of recycled crust in Icelandic basalts

Affiliations | Corresponding Author | Cite as | Funding informationKeywords: Melt-PX, Iceland, mantle heterogeneity, trace element, isotopic compositions, adiabatic decompression

- Share this article

Article views:9,313Cumulative count of HTML views and PDF downloads.

- Download Citation

- Rights & Permissions

top

Abstract

Figures and Tables

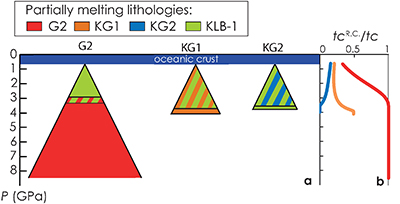

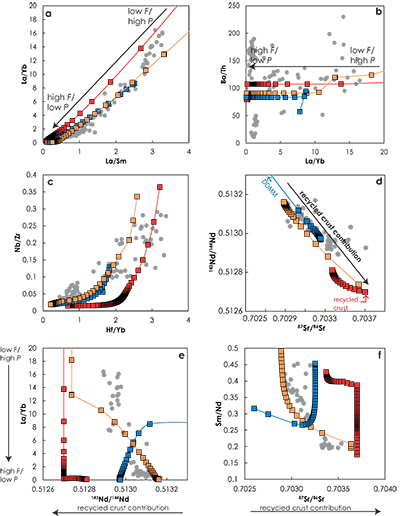

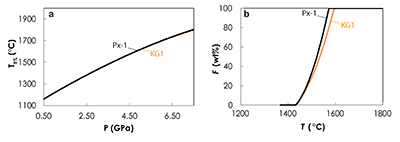

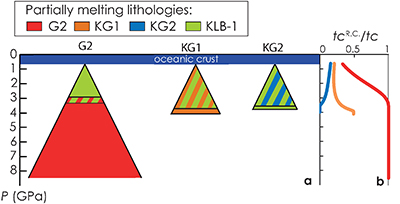

Figure 1 (a) Representation of the melting column in the three configurations. Colours show the lithologies that are partially melting at a given pressure. (b) Contribution of the recycled crust (tcR.C./tc) to the melt production as functions of the pressure along the adiabatic path in G2- (red), KG1- (orange) and KG2- (blue) configurations. The contribution of the recycled crust is assumed to be equal to the contribution of G2, to half of the contibution of KG1 and to one third of the contribution of KG2, in the respective configurations. |  Figure 2 Compositions of the aggregated melts produced over the melting column in G2- (red), KG1- (orange) and KG2- (blue) configurations. Grey dots are the compositions of Icelandic basalts with MgO contents between 9.5 and 17 wt. % from the Northern Volcanic zone, the Reykjanes Peninsula, the Snaefellsnes area and the South Eastern Volcanic Zone (GEOROC). Detailed explanations of the calculations are given in the Supplementary Information. |

| Figure 1 | Figure 2 |

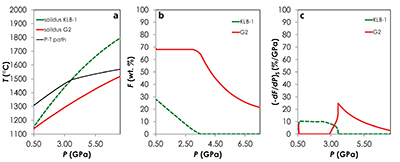

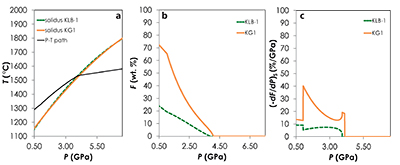

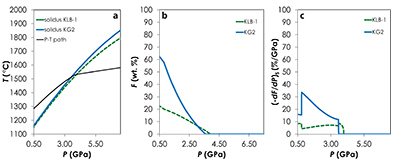

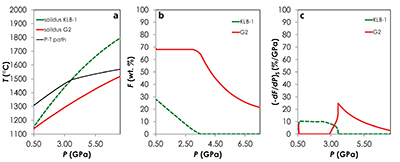

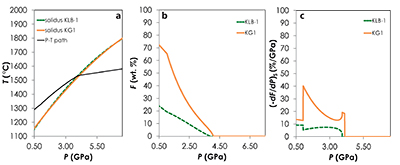

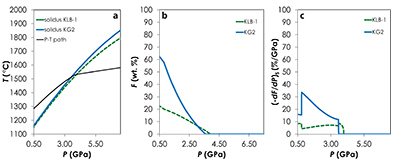

Supplementary Figures and Tables

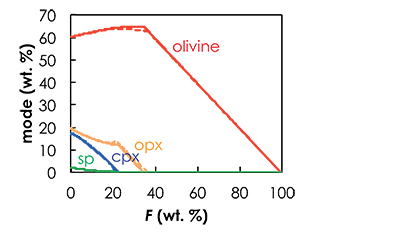

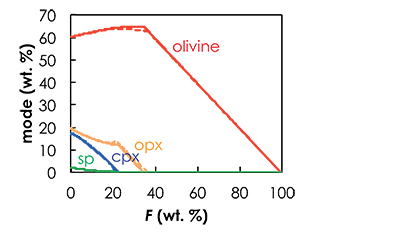

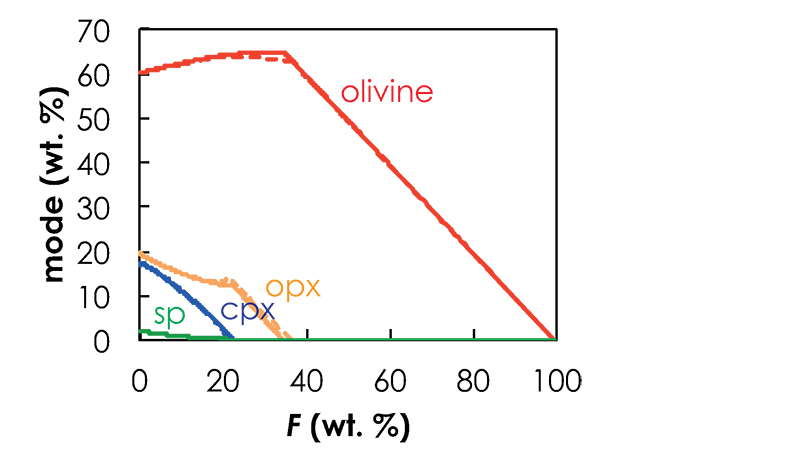

Figure S-1 Results of the Melt-PX calculations for the G2-configuration at a potential temperature of 1480 °C. (a) Pressure-temperature path for the column of mantle undergoing isentropic decompression (black line). The solid red and the dashed green lines are the solidi of G2 and KLB-1, respectively. (b-c) Extent of the melting (b) and melt productivity (c) of G2 (solid red line) and KLB-1 (dashed green line) along the adiabatic path. |  Figure S-2 Results of the Melt-PX calculations for the KG1-configuration at a potential temperature of 1480 °C. (a) Pressure-temperature path for the column of mantle undergoing isentropic decompression (black line). The solid orange and the dashed green lines are the solidi of KG1 and KLB-1, respectively. (b-c) Extent of the melting (b) and melt productivity (c) of KG1 (solid orange line) and KLB-1 (dashed green line) along the adiabatic path. |  Figure S-3 Results of the Melt-PX calculations for the KG2-configuration at a potential temperature of 1480 °C. (a) Pressure-temperature path for the column of mantle undergoing isentropic decompression (black line). The solid blue and the dashed green lines are the solidi of KG1 and KLB-1, respectively. (b-c) Extent of the melting (b) and melt productivity (c) of KG1 (solid blue line) and KLB-1 (dashed green line) along the adiabatic path. |  Figure S-4 Evolution of the solid phase modes for the composition KLB-1 (Hirose and Kushiro, 1993) as a function of the proportion of melt during batch melting (solid lines) and continuous melting (dashed lines). The threshold for melt segregation in the continuous melting calculations is 1 %. Calculations were performed at 1 GPa using the thermodynamic model pMELTS (Ghiorso et al., 2002) and the alphaMELTS front-end (Smith and Asimow, 2005). Olivine: red; orthopyroxene (opx): orange; clinopyroxene (cpx): blue; spinel (sp): green. |

| Figure S-1 | Figure S-2 | Figure S-3 | Figure S-4 |

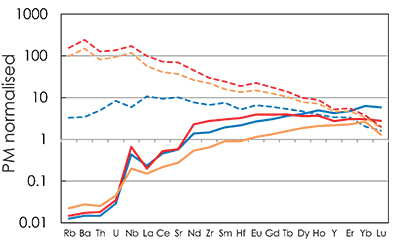

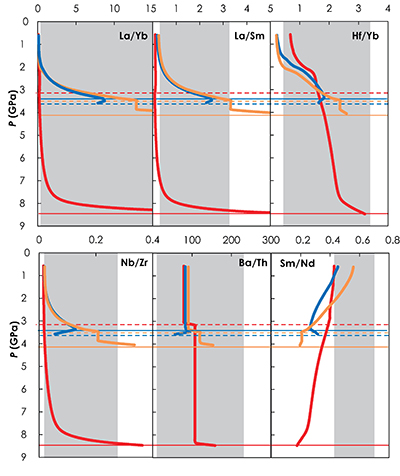

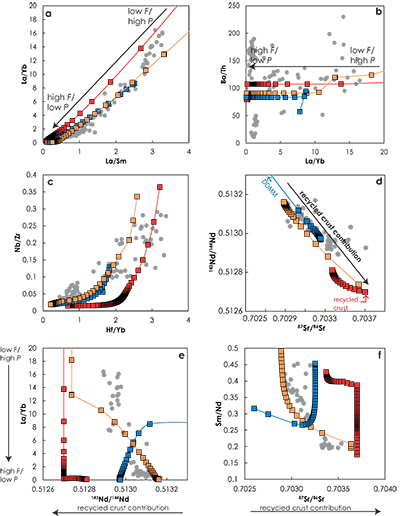

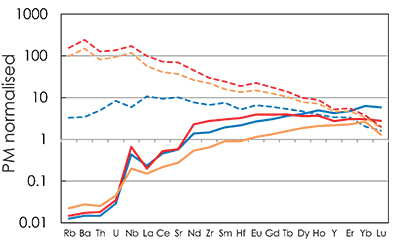

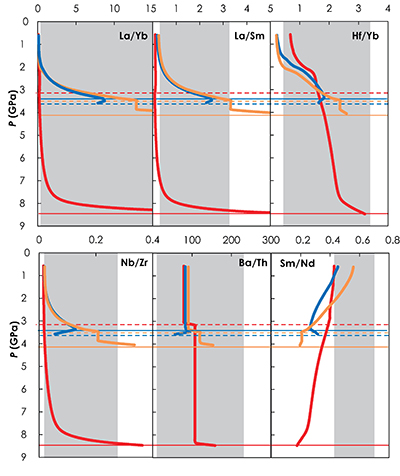

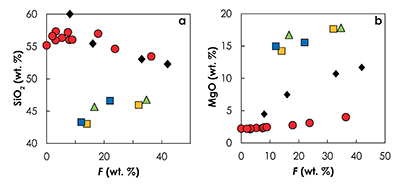

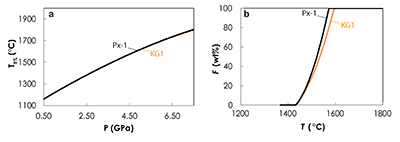

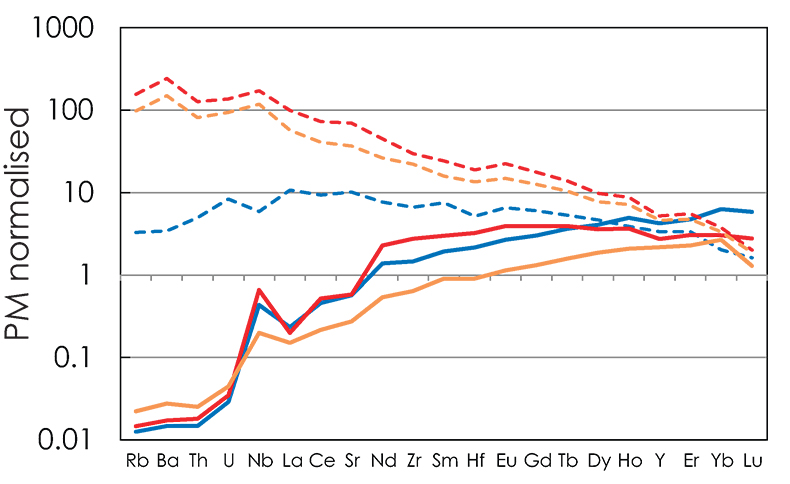

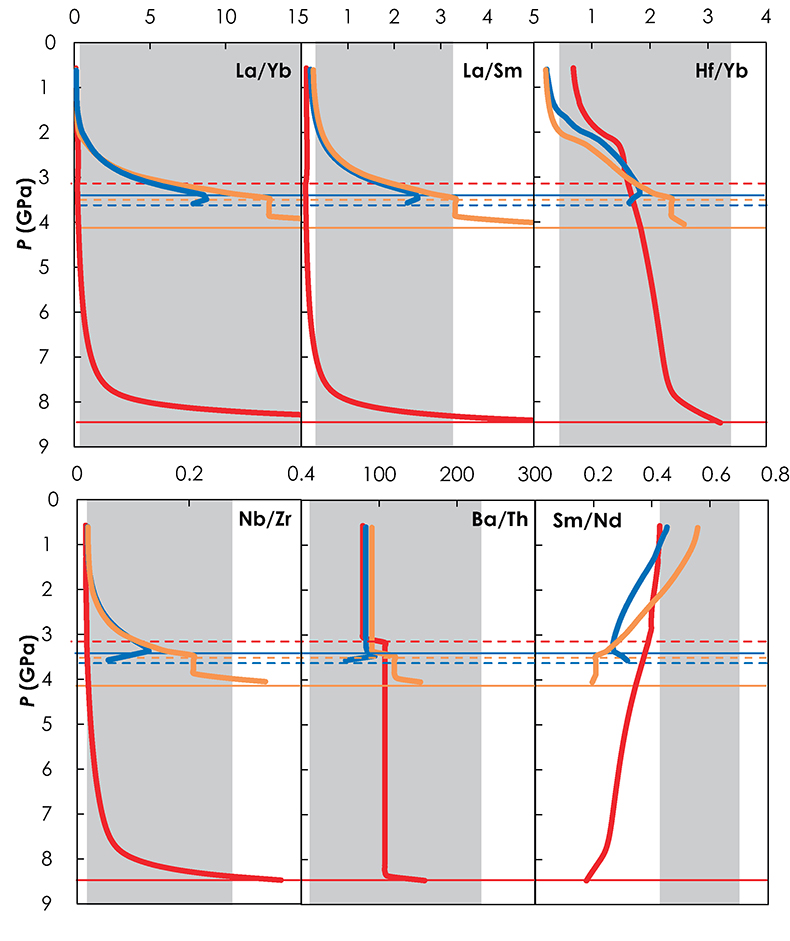

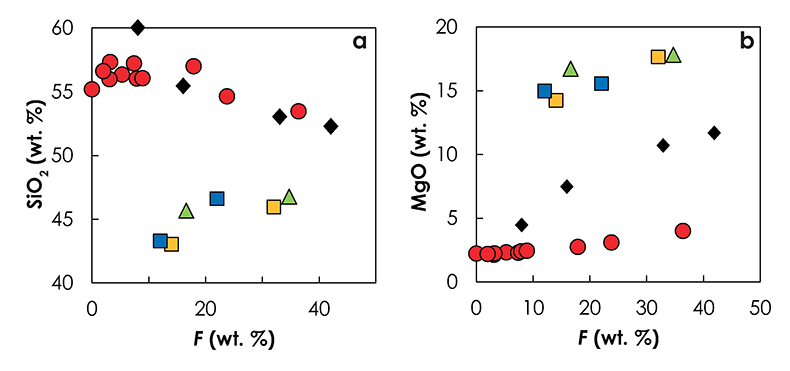

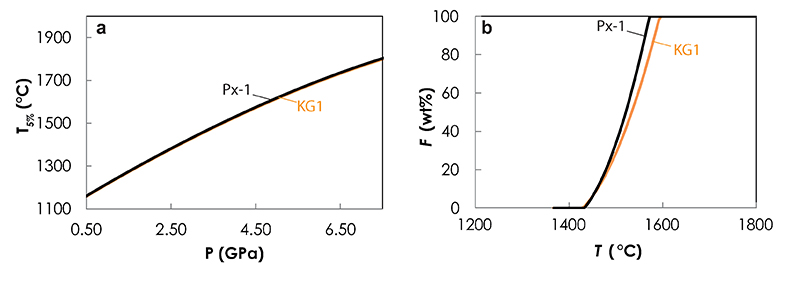

Figure S-5 Primitive mantle (PM; Sun and McDonough, 1989) normalised trace element patterns of the first degree melts (dashed lines) and the last accumulated melts produced at the base of the crust (solid lines) in G2- (red), KG1- (orange) and KG2- (blue) configurations. |  Figure S-6 Incompatible trace element ratios of the calculated accumulated melts as functions of the pressure in the three configurations (colour code is the same as in Fig. S-5). Solid lines represent the formation pressure of the first degree melt from the enriched mantle component (G2, KG1 or KG2) and dashed lines represent the formation pressure of the first degree melt from the peridotite component in the corresponding mantle configuration. The grey areas represent the range of compositional ratios in Icelandic basalts with MgO contents between 9.5 and 17 wt. % from the Northern Volcanic zone, the Reykjanes Peninsula, the Snaefellsnes area and the South Eastern Volcanic Zone (GEOROC). |  Figure S-7 Comparison of SiO2 (a) and MgO (b) contents of the melt produced by G2 (red circles; Pertermann and Hirschmann, 2003), KG1 and KG2 (orange and blue squares, respectively; Kogiso et al., 1998), Px-1 (black-diamond; Sobolev et al., 2007), and KLB-1 (green triangles; Hirose and Kushiro, 1993) at 3 GPa. |  Figure S-8 Near-solidus curves (T5%) (a) and melting curves at 3 GPa (b) calculated using Melt-PX (Lambart et al., 2016) for Px-1 (black; Sobolev et al., 2007) and KG1 (orange; Kogiso et al., 1998) compositions. |

| Figure S-5 | Figure S-6 | Figure S-7 | Figure S-8 |

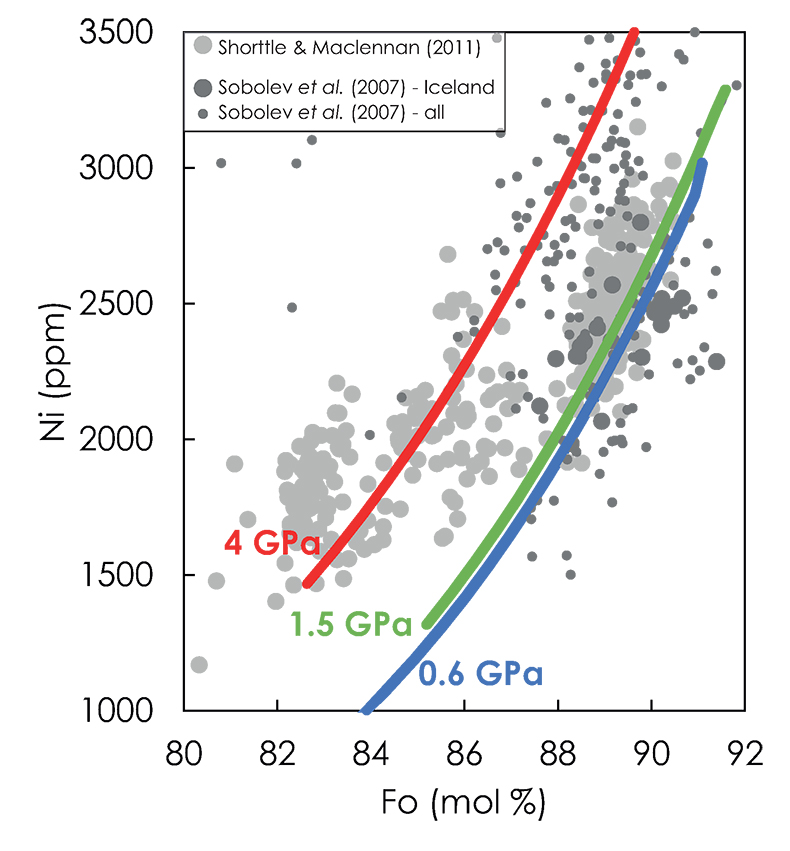

Figure S-9 Ni content of olivines from Icelandic basalts (large dark grey circles, Sobolev et al., 2007; large light grey circles, Shorttle and Maclennan, 2011). The lines are modelled olivine compositions produced by fractionally crystallising aggregated parental melts sampled at 4, 1.5 and 0.6 GPa along the adiabatic path in the KG1-configuration. The melts chosen for modelling are reported in Table S-3. Parental melts then had equilibrium olivine fractionally extracted from them at 1 bar using olivine compositions calculated with PRIMELT2.xls (Herzberg and Asimow, 2008) and according the Ni partitioning model of Matzen et al. (2017). Data from Sobolev et al. (2007) in other locations are also shown for comparison (small dark grey circles). See text for details of calculations. |  Table S-1 Majora, traceb element and isotopic compositions of G2, KLB-1, KG1, KG2 and Bulk1. |  Table S-2 Melt compositions and parameters used in olivine fractionation modelling. |  Table S-3 Compositions of the aggregated parental melt (APM) sampled at 4, 1.5 and 0.6 GPa and of the olivine in equilibrium at 1 bar. |

| Figure S-9 | Table S-1 | Table S-2 | Table S-3 |

top

Introduction

It is widely accepted that the compositional spectrum of Icelandic lavas requires the presence of at least two components in the mantle source (e.g., Thirlwall et al., 2004

Thirlwall, M.F., Gee, M.A.M., Taylor, R.N., Murton, B.J. (2004) Mantle components in Iceland and adjacent ridges investigated using double-spike Pb isotope ratios. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 68, 361–386.

, 2006Thirlwall, M.F., Gee, M.A.M., Lowry, D., Mattey, D.P., Murton, B.J., Taylor, R.N. (2006) Low δ18O in the Icelandic mantle and its origins: evidence from Reykjanes ridge and Icelandic lavas. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 70, 993–1019.

; Sobolev et al., 2007Sobolev, A.V., Hofmann, A.W., Kuzmin, D.V., Yaxley, G.M., Arndt, N.T., Chung, S.L., Danyushevsky, L.V., Elliott, T., Frey, F.A., Garcia, M.O., Gurenko, A.A., Kamenetsky, V.S., Kerr, A.C., Krivolutskaya, N.A., Matvienkov, V.V., Nikogosian, I.K., Rocholl, A., Sigurdsson, I.A., Sushchevskaya, N.M., Teklay, M. (2007) The amount of recycled crust in sources of mantle-derived melts. Science 316, 412–417.

; Brown and Lesher, 2014Brown, E.L., Lesher, C.E. (2014) North Atlantic magmatism controlled by temperature, mantle composition and buoyancy. Nature Geoscience 7, 820–824.

). However, the nature of these components is still debated and two end-member models have been suggested: while trace element and isotopic analyses of Icelandic lavas seem to suggest the presence of two distinct lithologies in the form of pyroxenite and peridotite (e.g., Kokfelt et al., 2006Kokfelt, T.F., Hoernle, K., Hauff, F., Fiebig, J., Werner R., Garbe-Schönberg, D. (2006) Combined Trace Element and Pb-Nd–Sr-O Isotope Evidence for Recycled Oceanic Crust (Upper and Lower) in the Iceland Mantle Plume. Journal of Petrology 47, 1705–1749.

; Koornneef et al., 2012Koornneef, J.M., Stracke, A., Bourdon, B., Meier, M.A., Jochum, K.P., Stoll, B., Grönvold, K. (2012) Melting of a Two-component Source beneath Iceland. Journal of Petrology 53, 127–157.

; Brown and Lesher, 2014Brown, E.L., Lesher, C.E. (2014) North Atlantic magmatism controlled by temperature, mantle composition and buoyancy. Nature Geoscience 7, 820–824.

), major-element compositions and olivine chemistry suggest a peridotite mantle composed of more or less re-fertilised domains by reaction with the recycling material (Shorttle and Maclennan, 2011Shorttle, O., Maclennan, J. (2011) Compositional trends of Icelandic basalts: Implications for short-length scale lithological heterogeneity in mantle plumes. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems 12, Q11008, doi:10.1029/2011GC003748.

; Herzberg et al., 2016Herzberg, C., Vidito, C., Starkey, N.A. (2016) Nickel-cobalt contents of olivine record origins of mantle peridotite and related rocks. American Mineralogist 101, 1952–1966.

). Using a quantitative melting model for the adiabatic decompression of a multi-lithological source, I show that trace element and isotopic compositions of the Icelandic basalt suite can be reproduced without involving the contribution of melts derived from the recycled basalt component in the mantle source.top

Strategy

Lambart et al. (2016)

Lambart, S., Baker, M.B., Stolper, E.M. (2016) The role of pyroxenite in basalt genesis: Melt-PX, a melting parameterization for mantle pyroxenites between 0.9 and 5GPa. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth 121, doi:10.1002/2015JB012762.

demonstrated that the final extent of melting and the mean melting pressure of the potential lithologies present in the mantle sources are strong functions of their major element composition. Hence, the same mantle bulk composition may melt differently and produce different trace element and isotopic melt compositions depending on the specific lithologies that are present and make up the bulk composition. To test this hypothesis, I considered a bulk mantle composition corresponding to 10 % recycled oceanic crust G2 + 90 % peridotite KLB-1 (Bulk1 in Table S-1) and compared the melting behaviour during adiabatic decompression at TP = 1480 °C of three different heterogeneity distributions in the mantle: G2-, KG1- and KG2-configurations. In the “G2-configuration”, the two distinct lithologies are the MORB-like type eclogite G2 (Pertermann and Hirschmann, 2003Pertermann, M., Hirschmann, M.M. (2003) Anhydrous Partial Melting Experiments on MORB-like Eclogite: Phase Relations, Phase Compositions and Mineral–Melt Partitioning of Major Elements at 2–3 GPa. Journal of Petrology 44, 2173–2201.

) and the peridotite KBL-1 (Hirose and Kushiro, 1993Hirose, K., Kushiro, I. (1993) Partial melting of dry peridotites at high pressures: Determiantion of compositions of melts segregated from peridotite using aggregates of diamond. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 114, 477–489.

). To model the KG1- and KG2-configurations, I considered a mantle containing 20 % lithology KG1 and 80 % peridotite KLB-1, and a mantle containing 30 % lithology KG2 and 70 % peridotite KLB-1, respectively. Because KG1 and KG2 (Kogiso et al., 1998Kogiso, T., Hirose, K., Takahashi, E. (1998) Melting experiments on homogeneous mixtures of peridotite and basalt: application to the genesis of ocean island basalts. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 162, 45–61.

) are two compositions produced by mixing 1/2 G2 and 1/2 KLB-1, and 1/3 G2 and 2/3 KLB-1, respectively, all three mantle configurations are isochemical (Bulk 1 in Table S-1). In the three configurations, the two lithologies present in the source are chemically isolated but in thermal equilibrium.Using Melt-PX (Lambart et al., 2016

Lambart, S., Baker, M.B., Stolper, E.M. (2016) The role of pyroxenite in basalt genesis: Melt-PX, a melting parameterization for mantle pyroxenites between 0.9 and 5GPa. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth 121, doi:10.1002/2015JB012762.

), I modelled the decompression melting of these three mantle configurations for a potential temperature TP = 1480 °C and calculated the trace element and isotopic compositions of the accumulated melts for complete mixing of melts from the two mantle components integrated over the melting column (Supplementary Information). Similar heterogeneous melting models have been described in the literature but, unlike those presented here, the melting behaviours of the different components were arbitrarily chosen (e.g., Ito and Mahoney, 2005Ito, G., Mahoney, J.J. (2005) Flow and melting of a heterogeneous mantle: 1. Method and importance to the geochemistry of ocean island and mid-ocean ridge basalts. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 230, 29–46.

; Stracke and Bourdon, 2009Stracke, A., Bourdon, B. (2009) The importance of melt extraction for tracing mantle heterogeneity. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 73, 218–238.

; Waters et al., 2011Waters, C.L., Sims, K.W.W., Perfit, M.R., Blichert-Toft, J., Blusztajn, J. (2011) Perspective on the Genesis of E-MORB from Chemical and Isotopic Heterogeneity at 9-10°N East Pacific Rise. Journal of Petrology 52, 565–602.

), the F versus T relationships were calculated with pMELTS (e.g., Rudge et al., 2013Rudge, J.F., Maclennan, J., Stracke, A. (2013) The geochemical consequences of mixing melts from a heterogeneous mantle. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 114, 112–143.

; Sims et al., 2013Sims, K.W.W., Maclennan, J., Blichert-Toft, J., Mervine, E.M., Blusztajn, J., Grönvold, K. (2013) Short length scale mantle heterogeneity beneath Iceland probed by glacial modulation of melting. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 379, 146–157.

) that strongly overestimates the size of melting interval of mantle lithologies and especially pyroxenites, by both overestimating the liquidus temperature and underestimating the solidus temperature (Lambart et al., 2016Lambart, S., Baker, M.B., Stolper, E.M. (2016) The role of pyroxenite in basalt genesis: Melt-PX, a melting parameterization for mantle pyroxenites between 0.9 and 5GPa. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth 121, doi:10.1002/2015JB012762.

), and/or the thermal interactions between components were not taken into account (e.g., Koornneef et al., 2012Koornneef, J.M., Stracke, A., Bourdon, B., Meier, M.A., Jochum, K.P., Stoll, B., Grönvold, K. (2012) Melting of a Two-component Source beneath Iceland. Journal of Petrology 53, 127–157.

). This study presents the first quantitative calculations taking into account the effect of the major element composition on the melting behaviours of the lithologies present in the source and on trace element and isotopic compositions of the magmas produced.top

Results

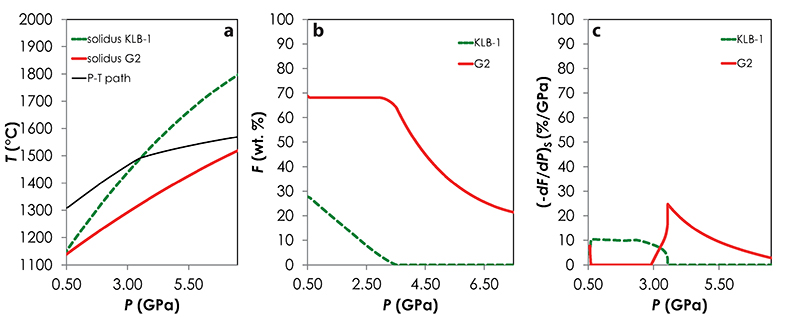

Results of the calculations with Melt-PX are illustrated in Figure 1. The mantle melting behaviour is much contrasted between the three configurations. In the G2-configuration, the pyroxenite component starts to melt at very high pressure (~8.7 GPa), but rapidly stops soon after the peridotite crosses its solidus (Fig. 1a). This phenomenon occurs because the adiabatic melting path is steeper than the solidus of G2 residue once the peridotite solidus is crossed (Fig. S-1; Lambart et al., 2016

Lambart, S., Baker, M.B., Stolper, E.M. (2016) The role of pyroxenite in basalt genesis: Melt-PX, a melting parameterization for mantle pyroxenites between 0.9 and 5GPa. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth 121, doi:10.1002/2015JB012762.

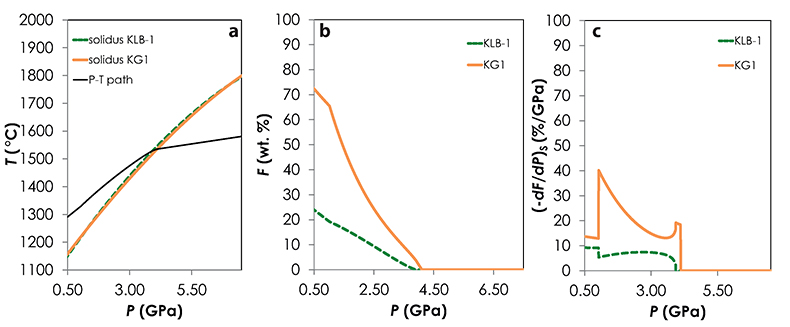

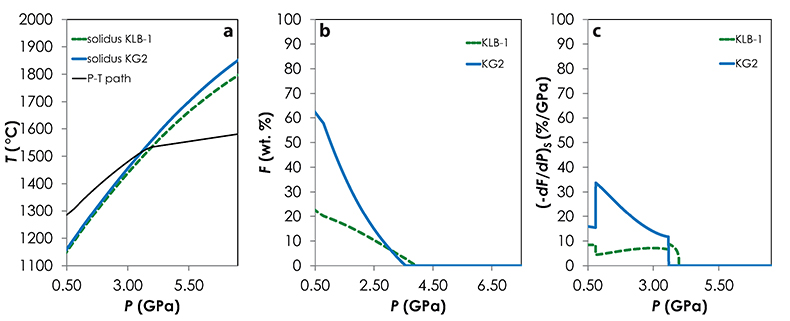

). Hence, partial melts generated along the adiabatic path are initially derived from the pyroxenite alone; once the peridotite starts to melt, the fraction of G2-derived melt in the aggregated liquid decreases by dilution with decreasing pressure (Fig. 1b). Unlike G2, lithology KG1 starts to melt just before the peridotite and, despite a drop of melt productivity when the peridotite solidus is crossed (Fig. S-2), both KG1 and KLB-1 continue to melt simultaneously. Finally, KG2 starts to melt after the peridotite but the melt productivity of KG2 is higher than the one of KLB-1 (Fig. S-3) and the fraction of KG2-derived liquid in the aggregated partial melt progressively increases with decreasing pressure (Fig. 1b). Despite these contrasting behaviours, the magmatic productivity and consequently the oceanic crust thickness produced in the three configurations are very similar with 21.8, 22.3 and 22.0 km for G2-, KG1- and KG2-configuration, respectively.

Figure 1 (a) Representation of the melting column in the three configurations. Colours show the lithologies that are partially melting at a given pressure. (b) Contribution of the recycled crust (tcR.C./tc) to the melt production as functions of the pressure along the adiabatic path in G2- (red), KG1- (orange) and KG2- (blue) configurations. The contribution of the recycled crust is assumed to be equal to the contribution of G2, to half of the contibution of KG1 and to one third of the contribution of KG2, in the respective configurations.

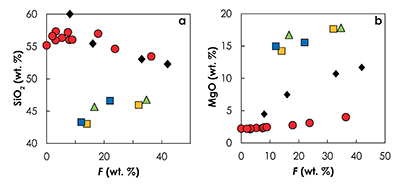

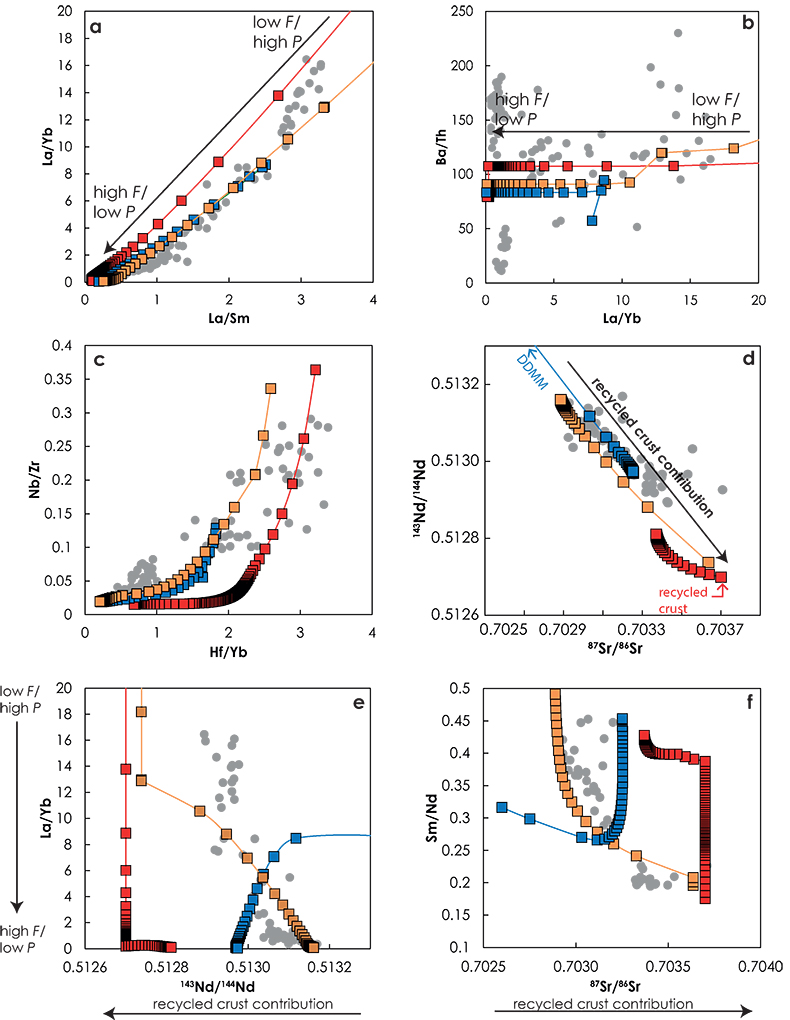

The trace element and isotopic compositions of the pooled melts for the three configurations along the adiabatic path are presented in Figure 2. Stracke and Bourdon (2009)

Stracke, A., Bourdon, B. (2009) The importance of melt extraction for tracing mantle heterogeneity. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 73, 218–238.

demonstrated that trace element ratios involving a moderately incompatible element (e.g., La/Sm, La/Yb, Hf/Yb) are dominantly influenced by the melting process. In fact La/Sm vs. La/Yb variations (Fig. 2a) show similar trends in the three configurations. On the contrary, highly incompatible element ratios, such as Ba/Th (Fig. 2b), do not vary significantly with progressive melting and differences between the ratios reflect differences in the source components. The three configurations show contrasting trends in the Sr-Nd isotopic space (Fig. 2d). Both G2- and KG1-configurations produced melts that become progressively less radiogenic due to the decrease of the recycled component contribution in the pooled melt along the adiabatic path (Fig. 1b). Interestingly, the range of isotopic compositions produced in G2-configuration is much smaller than the one produced in KG1-configuration. KG2-configuration produces melts that become increasingly radiogenic with decreasing pressure due to the increase of recycled crust contribution along the adiabatic path (Fig. 1b). Finally, correlations between trace element ratios and isotopic ratios show very distinctive trends for the three configurations (Fig. 2e-f). In the G2-configuration, the 143Nd/144Nd of the pooled melt stays constant as long as only G2 is melting, while the La/Yb ratio decreases with increasing F. When the peridotite starts to melt, G2 has reached 57 wt. % melting and the accumulated melt is much depleted in incompatible trace elements. The addition of an isotopically depleted peridotite partial melt results in a shift of the pooled liquid isotopic composition, while the La/Yb ratio stays relatively constant (Fig. 2e). In the KG1-configuration, KG1 only reached 13 wt. % melting at the onset of the peridotite melting. Hence, the La/Yb ratio continues to decrease with the increasing melting degree of KG1 while the addition of peridotite melt increases the isotopic ratio 143Nd/144Nd of the pooled melt. Finally, in the KG2-configuration, the peridotite starts to melt before KG2 and the first degree melt is a peridotite liquid at 3.6 GPa (Figs. 1, S-5). Soon after, the solidus of KG2 is crossed and the aggregated melt becomes more isotopically enriched due to the addition of KG2-derived melt (the 143Nd/144Nd ratio decreases and the 86Sr/87Sr ratio increases with decreasing pressure; Fig. 2e-f).

Figure 2 Compositions of the aggregated melts produced over the melting column in G2- (red), KG1- (orange) and KG2- (blue) configurations. Grey dots are the compositions of Icelandic basalts with MgO contents between 9.5 and 17 wt. % from the Northern Volcanic zone, the Reykjanes Peninsula, the Snaefellsnes area and the South Eastern Volcanic Zone (GEOROC). Detailed explanations of the calculations are given in the Supplementary Information.

top

Implications for the Nature of the Mantle Heterogeneity Beneath Iceland

Several studies have questioned the necessity to involve the direct contribution of melts from the recycled component to the magmatic production beneath Iceland (Shorttle and Maclennan, 2011

Shorttle, O., Maclennan, J. (2011) Compositional trends of Icelandic basalts: Implications for short-length scale lithological heterogeneity in mantle plumes. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems 12, Q11008, doi:10.1029/2011GC003748.

; Herzberg et al, 2016Herzberg, C., Vidito, C., Starkey, N.A. (2016) Nickel-cobalt contents of olivine record origins of mantle peridotite and related rocks. American Mineralogist 101, 1952–1966.

). On Figure 2, I compared the calculated trends with the observed variation in Icelandic basalts produced in the rift zones at the coasts (GEOROC database). Consistent with the calculations, magma production in this context is thought to reflect a passive plate spreading alone (Brown and Lesher, 2014Brown, E.L., Lesher, C.E. (2014) North Atlantic magmatism controlled by temperature, mantle composition and buoyancy. Nature Geoscience 7, 820–824.

, Shorttle et al., 2014Shorttle, O., Maclennan, J., Lambart, S. (2014) Quantifying lithological variability in the mantle. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 395, 24–40.

) and TP = 1480 °C is in agreement with the most recent estimated potential mantle temperature beneath Iceland (Matthews et al., 2016Matthews, S., Shorttle, O., Maclennan, J. (2016) The temperature of the Icelandic mantle from olivine-spinel aluminum exchange thermometry. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems 17, 4725–4752.

). Calculated crust thicknesses are in fact similar to the estimated crustal thicknesses in Iceland's rift zones (Darbyshire et al., 2000Darbyshire, F.A., White, R.S., Priestley, K.F. (2000) Structure of the crust and uppermost mantle of Iceland from a combined seismic and gravity study. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 181, 409–428.

). In addition, these calculations suggest that in the context of passive melting regime, the volume of magma produced is relatively independent of the nature of the lithological heterogeneity, but is mainly controlled by the mantle potential temperature (Lambart et al., 2016Lambart, S., Baker, M.B., Stolper, E.M. (2016) The role of pyroxenite in basalt genesis: Melt-PX, a melting parameterization for mantle pyroxenites between 0.9 and 5GPa. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth 121, doi:10.1002/2015JB012762.

) and the bulk mantle composition. Calculations show that the trace element – isotope systematics are mostly controlled by the pressure difference between the onset of melting of the lithologies present in the source (Stracke and Bourdon, 2009Stracke, A., Bourdon, B. (2009) The importance of melt extraction for tracing mantle heterogeneity. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 73, 218–238.

). Overall, the trace element and isotopic systematics of Icelandic basalts are well reproduced by the melting of a mantle containing 20 % KG1. In detail, the trace element compositions of Icelandic basalts become more depleted with increasing 143Nd/144Nd ratios (Fig. 2e) and decreasing 87Sr/86Sr (Fig. 2f). In other words, the progressive depletion of the Icelandic melts with increasing extent of melting indicates that the enriched component becomes progressively diluted with the peridotite component. This is only possible if the enriched component has a lower solidus temperature compared to the depleted component, in agreement with Sims et al. (2013)Sims, K.W.W., Maclennan, J., Blichert-Toft, J., Mervine, E.M., Blusztajn, J., Grönvold, K. (2013) Short length scale mantle heterogeneity beneath Iceland probed by glacial modulation of melting. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 379, 146–157.

. Moreover, Figure 2 suggests that a small difference in solidus temperature of the enriched and depleted components is required to reproduce the co-variations between trace element and isotopic ratios, especially those involving highly incompatible elements over moderately incompatible elements (Fig. 2e-f). Otherwise, for large solidus temperature differences between the two components, such as in G2-configuration, the enriched component will undergo large degree of melting before onset of the peridotite melting resulting in insufficient enrichment of melts in highly incompatible elements. Hence, by using Melt-PX to model the melting behaviour of the mantle components, this study provides quantitative constraints on the melting behaviour, and consequently on the major-element composition, of the lithologies present in the source.It could be argued that the absolute positions of the compositional trends along the isotopic ratio axes in Figure 2e-f depend on the isotopic compositions chosen for the peridotite and the recycled components (Table S-1). For the peridotite component, I chose the isotopic composition of the most depleted end of the MORB field reported by Salters and Stracke (2004)

Salters, V.J.M., Stracke, A. (2004) Composition of the depleted mantle. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems 5, Q05004, doi:10.1029/2003GC000597.

. In fact, unradiogenic Pb isotopic compositions, Nd and Hf isotope systems and trace element systematics of Icelandic basalts have all been used to validate the presence of a distinct depleted endmember for the Iceland plume (e.g., Thirlwall et al., 2004Thirlwall, M.F., Gee, M.A.M., Taylor, R.N., Murton, B.J. (2004) Mantle components in Iceland and adjacent ridges investigated using double-spike Pb isotope ratios. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 68, 361–386.

, 2006Thirlwall, M.F., Gee, M.A.M., Lowry, D., Mattey, D.P., Murton, B.J., Taylor, R.N. (2006) Low δ18O in the Icelandic mantle and its origins: evidence from Reykjanes ridge and Icelandic lavas. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 70, 993–1019.

; Shorttle et al., 2014Shorttle, O., Maclennan, J., Lambart, S. (2014) Quantifying lithological variability in the mantle. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 395, 24–40.

and references therein). For the recycled crustal component, I chose a 2 Ga recycled crust (e.g., Chauvel and Hémond, 2000Chauvel, C., Hémond, C. (2000) Melting of a complete section of recycled oceanic crust: Trace element and Pb isotopic evidence from Iceland. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems 1, 1001.

; Kokfelt et al., 2006Kokfelt, T.F., Hoernle, K., Hauff, F., Fiebig, J., Werner R., Garbe-Schönberg, D. (2006) Combined Trace Element and Pb-Nd–Sr-O Isotope Evidence for Recycled Oceanic Crust (Upper and Lower) in the Iceland Mantle Plume. Journal of Petrology 47, 1705–1749.

). However, the age of the recycled component in the basalt source of Iceland is highly debated and could be younger by up to an order of magnitude (Halldórsson et al., 2016Halldórsson, S.A., Hilton, D.R., Barry, P.H., Füri, E., Grönvold, K. (2016) Recycling of crustal material by the Iceland mantle plume: New evidence from nitrogen elemental and isotope systematics of subglacial basalts. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 176, 206–226.

). A younger recycled material will have a lower content of radiogenic isotopes and consequently trends in Figure 2e-f will be shifted toward higher 143Nd/144Nd ratios and lower the 87Sr/86Sr ratios. For instance, the range of Nd isotopic compositions displayed by the Icelandic basalt (Fig. 2d) could be reproduced in the G2-configuration by varying the age of the recycled component from 1.7 to 0.5 Ga, but would not explain the co-variations between trace element and isotopic ratios (Fig. 2e). In the following section I provide additional constraints on the nature of the mantle heterogeneity beneath Iceland by looking at the implications of these observations for melt extraction mechanisms.top

Constraints from Melt Extraction

It was shown in the preceding section that (1) the compositional variability of Icelandic basalt requires at least two different mantle components with different radiogenic isotopic compositions, (2) the most radiogenic component should have the lowest solidus temperature (as in G2- or KG1-configurations), and equally importantly (3) the pooled melts need to be extracted at different depths along the adiabatic path, in agreement with the conclusions of Stracke and Bourdon (2009)

Stracke, A., Bourdon, B. (2009) The importance of melt extraction for tracing mantle heterogeneity. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 73, 218–238.

. This last observation implies an efficient melt extraction mechanism capable of sampling relatively low degree partial melts without significant interaction with the mantle. In the G2-configuration, the peridotite mostly stays subsolidus during the melting of the pyroxenite (Fig. 1a) and the highest La/Yb (>12) and La/Sm (>3) ratios displayed by the Icelandic basalts (Fig. 2a) are produced at P > 8.3 GPa (Fig. S-6). Hence, the G2-configuration requires the unlikely scenario of the circulation of a very silica-rich (Fig. S-7) low-degree melt into a subsolidus peridotite mantle from 8.3 GPa to 3.1 GPa (the onset of peridotite melting) and without significant melt-rock interaction. In the KG1-configuration, the peridotite starts to melt soon after the enriched component (Fig. 1a) and the highest La/Yb and La/Sm ratios are produced at P > 3.4 GPa, i.e. by the melting of the KG1 component only. However, unlike G2, KG1 produces melts with major element compositions very similar to peridotite melts (Fig. S-7). This small compositional contrast will result in limited reactivity between KG1-derived melt and peridotite, favourable to the preservation of their trace element signature (Lambart et al., 2012Lambart, S., Laporte, D., Provost, A., Schiano, P. (2012) Fate of pyroxenite-derived melts in the peridotitic mantle: Thermodynamical and experimental constraints. Journal of Petrology 53, 451–476.

). Finally, it should be noted that, in the G2-configuration, the entire range of trace element compositions observed in Icelandic basalts is produced by the melting of the pyroxenite G2 while the peridotite component stays subsolidus. Lambart et al. (2012)Lambart, S., Laporte, D., Provost, A., Schiano, P. (2012) Fate of pyroxenite-derived melts in the peridotitic mantle: Thermodynamical and experimental constraints. Journal of Petrology 53, 451–476.

showed that migration of melts in a subsolidus mantle results in a strong consumption of the melt. On the contrary, melt extraction is facilitated when the surrounding mantle is partially melted, as in the KG1-configuration in which, with the exception of the most enriched basalt compositions (La/Yb > 12 and La/Sm > 3), both KG1 and KLB-1 are contributing to the pooled melts (Fig. S-6).top

Solid-State Reaction Versus Melt–Rock Reaction

Calculations presented above resolve an ambiguity that has arisen in the literature, between the need for the direct contribution of melts from recycled basaltic lithologies, versus the manifestation of their presence through re-fertilised hybrid lithologies, and demonstrate that hybrid lithologies can be an important contributor to lithological diversity in the mantle. However, these hybrid lithologies could be formed either by solid-state reaction (i.e. homogeneous mixing and phase equilibration between the solid recycled crust and the solid peridotite) or by melt-rock reaction, in which melts derived from the recycled crust react with the peridotite to form an olivine-free secondary pyroxenite, such as Px-1 (Sobolev et al., 2007

Sobolev, A.V., Hofmann, A.W., Kuzmin, D.V., Yaxley, G.M., Arndt, N.T., Chung, S.L., Danyushevsky, L.V., Elliott, T., Frey, F.A., Garcia, M.O., Gurenko, A.A., Kamenetsky, V.S., Kerr, A.C., Krivolutskaya, N.A., Matvienkov, V.V., Nikogosian, I.K., Rocholl, A., Sigurdsson, I.A., Sushchevskaya, N.M., Teklay, M. (2007) The amount of recycled crust in sources of mantle-derived melts. Science 316, 412–417.

). Because KG1 and Px-1 have similar solidus and melting curves (Fig. S-8; Lambart et al., 2016Lambart, S., Baker, M.B., Stolper, E.M. (2016) The role of pyroxenite in basalt genesis: Melt-PX, a melting parameterization for mantle pyroxenites between 0.9 and 5GPa. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth 121, doi:10.1002/2015JB012762.

), the trace element – isotope systematics that would be produced by an isochemical bulk mantle containing Px-1 would be very similar to the one produced by the KG1-configuration and would not lead to the discrimination between both models. Similarly, both models can reproduce the high nickel content of primitive Icelandic olivine (Fig. S-9). However, one major difference between these two models, is the major-element composition of the hybrid lithology and consequently, of the derived melts produced by these lithologies. In fact, olivine-free secondary pyroxenites produced melts with similar silica content to G2-derived melts (Fig. S-7). As mentioned above, such melts are likely to react with the surrounding peridotite to produce pyroxenes and dissolve olivine and, consequently, are less likely to preserve their compositional signature.In summary, this study supports the fact that two distinct mantle components are required to explain the compositional diversity of Icelandic basalts with the most radiogenic component being the most fusible, but also demonstrates that the direct contribution of the melts derived from the recycled crust cannot explain the trace element - isotope systematics of Icelandic basalt, and rather advances the polybaric melting of various olivine-bearing lithologies, likely produced by solid-state interactions between the recycled crust and the peridotite.

top

Acknowledgements

This study has benefited from discussions with Mike Baker and Ed Stolper. This work was supported by the National Science Foundation grant EAR-1551442 and the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 663830. Two anonymous reviewers are thanked for their helpful suggestions.

Editor: Graham Pearson

top

References

Brown, E.L., Lesher, C.E. (2014) North Atlantic magmatism controlled by temperature, mantle composition and buoyancy. Nature Geoscience 7, 820–824.

Show in context

Show in context It is widely accepted that the compositional spectrum of Icelandic lavas requires the presence of at least two components in the mantle source (e.g., Thirlwall et al., 2004, 2006; Sobolev et al., 2007; Brown and Lesher, 2014).

View in article

However, the nature of these components is still debated and two end-member models have been suggested: while trace element and isotopic analyses of Icelandic lavas seem to suggest the presence of two distinct lithologies in the form of pyroxenite and peridotite (e.g., Kokfelt et al., 2006; Koornneef et al., 2012; Brown and Lesher, 2014), major-element compositions and olivine chemistry suggest a peridotite mantle composed of more or less re-fertilised domains by reaction with the recycling material (Shorttle and Maclennan, 2011; Herzberg et al., 2016).

View in article

Consistent with the calculations, magma production in this context is thought to reflect a passive plate spreading alone (Brown and Lesher, 2014, Shorttle et al., 2014) and TP = 1480 °C is in agreement with the most recent estimated potential mantle temperature beneath Iceland (Matthews et al., 2016).

View in article

Chauvel, C., Hémond, C. (2000) Melting of a complete section of recycled oceanic crust: Trace element and Pb isotopic evidence from Iceland. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems 1, 1001.

Show in context

Show in context For the recycled crustal component, I chose a 2 Ga recycled crust (e.g., Chauvel and Hémond, 2000; Kokfelt et al., 2006).

View in article

Darbyshire, F.A., White, R.S., Priestley, K.F. (2000) Structure of the crust and uppermost mantle of Iceland from a combined seismic and gravity study. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 181, 409–428.

Show in context

Show in context Calculated crust thicknesses are in fact similar to the estimated crustal thicknesses in Iceland's rift zones (Darbyshire et al., 2000).

View in article

Halldórsson, S.A., Hilton, D.R., Barry, P.H., Füri, E., Grönvold, K. (2016) Recycling of crustal material by the Iceland mantle plume: New evidence from nitrogen elemental and isotope systematics of subglacial basalts. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 176, 206–226.

Show in context

Show in context However, the age of the recycled component in the basalt source of Iceland is highly debated and could be younger by up to an order of magnitude (Halldórsson et al., 2016).

View in article

Herzberg, C., Vidito, C., Starkey, N.A. (2016) Nickel-cobalt contents of olivine record origins of mantle peridotite and related rocks. American Mineralogist 101, 1952–1966.

Show in context

Show in context However, the nature of these components is still debated and two end-member models have been suggested: while trace element and isotopic analyses of Icelandic lavas seem to suggest the presence of two distinct lithologies in the form of pyroxenite and peridotite (e.g., Kokfelt et al., 2006; Koornneef et al., 2012; Brown and Lesher, 2014), major-element compositions and olivine chemistry suggest a peridotite mantle composed of more or less re-fertilised domains by reaction with the recycling material (Shorttle and Maclennan, 2011; Herzberg et al., 2016).

View in article

Several studies have questioned the necessity to involve the direct contribution of melts from the recycled component to the magmatic production beneath Iceland (Shorttle and MacLennan, 2011; Herzberg et al., 2016).

View in article

Hirose, K., Kushiro, I. (1993) Partial melting of dry peridotites at high pressures: Determiantion of compositions of melts segregated from peridotite using aggregates of diamond. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 114, 477–489.

Show in context

Show in context In the “G2-configuration”, the two distinct lithologies are the MORB-like type eclogite G2 (Pertermann and Hirschmann, 2003) and the peridotite KBL-1 (Hirose and Kushiro, 1993).

View in article

Ito, G., Mahoney, J.J. (2005) Flow and melting of a heterogeneous mantle: 1. Method and importance to the geochemistry of ocean island and mid-ocean ridge basalts. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 230, 29–46.

Show in context

Show in context Similar heterogeneous melting models have been described in the literature but, unlike those presented here, the melting behaviours of the different components were arbitrarily chosen (e.g., Ito and Mahoney, 2005; Stracke and Bourdon, 2009; Waters et al., 2011), the F versus T relationships were calculated with pMELTS (e.g., Rudge et al., 2013; Sims et al., 2013) that strongly overestimates the size of melting interval of mantle lithologies and especially pyroxenites, by both overestimating the liquidus temperature and underestimating the solidus temperature (Lambart et al., 2016), and/or the thermal interactions between components were not taken into account (e.g., Koornneef et al., 2012).

View in article

Kogiso, T., Hirose, K., Takahashi, E. (1998) Melting experiments on homogeneous mixtures of peridotite and basalt: application to the genesis of ocean island basalts. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 162, 45–61.

Show in context

Show in context Because KG1 and KG2 (Kogiso et al., 1998) are two compositions produced by mixing 1/2 G2 and 1/2 KLB-1, and 1/3 G2 and 2/3 KLB-1, respectively, all three mantle configurations are isochemical (Bulk 1 in Table S-1).

View in article

Kokfelt, T.F., Hoernle, K., Hauff, F., Fiebig, J., Werner R., Garbe-Schönberg, D. (2006) Combined Trace Element and Pb-Nd–Sr-O Isotope Evidence for Recycled Oceanic Crust (Upper and Lower) in the Iceland Mantle Plume. Journal of Petrology 47, 1705–1749.

Show in context

Show in context However, the nature of these components is still debated and two end-member models have been suggested: while trace element and isotopic analyses of Icelandic lavas seem to suggest the presence of two distinct lithologies in the form of pyroxenite and peridotite (e.g., Kokfelt et al., 2006; Koornneef et al., 2012; Brown and Lesher, 2014), major-element compositions and olivine chemistry suggest a peridotite mantle composed of more or less re-fertilised domains by reaction with the recycling material (Shorttle and Maclennan, 2011; Herzberg et al., 2016).

View in article

For the recycled crustal component, I chose a 2 Ga recycled crust (e.g., Chauvel and Hémond, 2000; Kokfelt et al., 2006).

View in article

Koornneef, J.M., Stracke, A., Bourdon, B., Meier, M.A., Jochum, K.P., Stoll, B., Grönvold, K. (2012) Melting of a Two-component Source beneath Iceland. Journal of Petrology 53, 127–157.

Show in context

Show in context However, the nature of these components is still debated and two end-member models have been suggested: while trace element and isotopic analyses of Icelandic lavas seem to suggest the presence of two distinct lithologies in the form of pyroxenite and peridotite (e.g., Kokfelt et al., 2006; Koornneef et al., 2012; Brown and Lesher, 2014), major-element compositions and olivine chemistry suggest a peridotite mantle composed of more or less re-fertilised domains by reaction with the recycling material (Shorttle and Maclennan, 2011; Herzberg et al., 2016).

View in article

Similar heterogeneous melting models have been described in the literature but, unlike those presented here, the melting behaviours of the different components were arbitrarily chosen (e.g., Ito and Mahoney, 2005; Stracke and Bourdon, 2009; Waters et al., 2011), the F versus T relationships were calculated with pMELTS (e.g., Rudge et al., 2013; Sims et al., 2013) that strongly overestimates the size of melting interval of mantle lithologies and especially pyroxenites, by both overestimating the liquidus temperature and underestimating the solidus temperature (Lambart et al., 2016), and/or the thermal interactions between components were not taken into account (e.g., Koornneef et al., 2012).

View in article

Lambart, S., Laporte, D., Provost, A., Schiano, P. (2012) Fate of pyroxenite-derived melts in the peridotitic mantle: Thermodynamical and experimental constraints. Journal of Petrology 53, 451–476.

Show in context

Show in context This small compositional contrast will result in limited reactivity between KG1-derived melt and peridotite, favourable to the preservation of their trace element signature (Lambart et al., 2012).

View in article

Lambart et al. (2012) showed that migration of melts in a subsolidus mantle results in a strong consumption of the melt.

View in article

Lambart, S., Baker, M.B., Stolper, E.M. (2016) The role of pyroxenite in basalt genesis: Melt-PX, a melting parameterization for mantle pyroxenites between 0.9 and 5GPa. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth 121, doi:10.1002/2015JB012762.

Show in context

Show in context Lambart et al. (2016) demonstrated that the final extent of melting and the mean melting pressure of the potential lithologies present in the mantle sources are strong functions of their major element composition.

View in article

Using Melt-PX (Lambart et al., 2016), I modelled the decompression melting of these three mantle configurations for a potential temperature TP = 1480 °C and calculated the trace element and isotopic compositions of the accumulated melts for complete mixing of melts from the two mantle components integrated over the melting column (Supplementary Information).

View in article

Similar heterogeneous melting models have been described in the literature but, unlike those presented here, the melting behaviours of the different components were arbitrarily chosen (e.g., Ito and Mahoney, 2005; Stracke and Bourdon, 2009; Waters et al., 2011), the F versus T relationships were calculated with pMELTS (e.g., Rudge et al., 2013; Sims et al., 2013) that strongly overestimates the size of melting interval of mantle lithologies and especially pyroxenites, by both overestimating the liquidus temperature and underestimating the solidus temperature (Lambart et al., 2016), and/or the thermal interactions between components were not taken into account (e.g., Koornneef et al., 2012).

View in article

This phenomenon occurs because the adiabatic melting path is steeper than the solidus of G2 residue once the peridotite solidus is crossed (Fig. S-1; Lambart et al., 2016).

View in article

In addition, these calculations suggest that in the context of passive melting regime, the volume of magma produced is relatively independent of the nature of the lithological heterogeneity, but is mainly controlled by the mantle potential temperature (Lambart et al., 2016) and the bulk mantle composition.

View in article

Because KG1 and Px-1 have similar solidus and melting curves (Fig. S-8; Lambart et al., 2016), the trace element – isotope systematics that would be produced by an isochemical bulk mantle containing Px-1 would be very similar to the one produced by the KG1-configuration and would not lead to the discrimination between both models.

View in article

Matthews, S., Shorttle, O., Maclennan, J. (2016) The temperature of the Icelandic mantle from olivine-spinel aluminum exchange thermometry. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems 17, 4725–4752.

Show in context

Show in context Consistent with the calculations, magma production in this context is thought to reflect a passive plate spreading alone (Brown and Lesher, 2014, Shorttle et al., 2014) and TP = 1480 °C is in agreement with the most recent estimated potential mantle temperature beneath Iceland (Matthews et al., 2016).

View in article

Pertermann, M., Hirschmann, M.M. (2003) Anhydrous Partial Melting Experiments on MORB-like Eclogite: Phase Relations, Phase Compositions and Mineral–Melt Partitioning of Major Elements at 2–3 GPa. Journal of Petrology 44, 2173–2201.

Show in context

Show in context In the “G2-configuration”, the two distinct lithologies are the MORB-like type eclogite G2 (Pertermann and Hirschmann, 2003) and the peridotite KBL-1 (Hirose and Kushiro, 1993).

View in article

Rudge, J.F., Maclennan, J., Stracke, A. (2013) The geochemical consequences of mixing melts from a heterogeneous mantle. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 114, 112–143.

Show in context

Show in context Similar heterogeneous melting models have been described in the literature but, unlike those presented here, the melting behaviours of the different components were arbitrarily chosen (e.g., Ito and Mahoney, 2005; Stracke and Bourdon, 2009; Waters et al., 2011), the F versus T relationships were calculated with pMELTS (e.g., Rudge et al., 2013; Sims et al., 2013) that strongly overestimates the size of melting interval of mantle lithologies and especially pyroxenites, by both overestimating the liquidus temperature and underestimating the solidus temperature (Lambart et al., 2016), and/or the thermal interactions between components were not taken into account (e.g., Koornneef et al., 2012).

View in article

Salters, V.J.M., Stracke, A. (2004) Composition of the depleted mantle. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems 5, Q05004, doi:10.1029/2003GC000597.

Show in context

Show in context For the peridotite component, I chose the isotopic composition of the most depleted end of the MORB field reported by Salters and Stracke (2004).

View in article

Shorttle, O., Maclennan, J. (2011) Compositional trends of Icelandic basalts: Implications for short-length scale lithological heterogeneity in mantle plumes. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems 12, Q11008, doi:10.1029/2011GC003748.

Show in context

Show in context However, the nature of these components is still debated and two end-member models have been suggested: while trace element and isotopic analyses of Icelandic lavas seem to suggest the presence of two distinct lithologies in the form of pyroxenite and peridotite (e.g., Kokfelt et al., 2006; Koornneef et al., 2012; Brown and Lesher, 2014), major-element compositions and olivine chemistry suggest a peridotite mantle composed of more or less re-fertilised domains by reaction with the recycling material (Shorttle and Maclennan, 2011; Herzberg et al., 2016).

View in article

Several studies have questioned the necessity to involve the direct contribution of melts from the recycled component to the magmatic production beneath Iceland (Shorttle and MacLennan, 2011; Herzberg et al., 2016).

View in article

Shorttle, O., Maclennan, J., Lambart, S. (2014) Quantifying lithological variability in the mantle. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 395, 24–40.

Show in context

Show in context Consistent with the calculations, magma production in this context is thought to reflect a passive plate spreading alone (Brown and Lesher, 2014, Shorttle et al., 2014) and TP = 1480 °C is in agreement with the most recent estimated potential mantle temperature beneath Iceland (Matthews et al., 2016).

View in article

In fact, unradiogenic Pb isotopic compositions, Nd and Hf isotope systems and trace element systematics of Icelandic basalts have all been used to validate the presence of a distinct depleted endmember for the Iceland plume (e.g., Thirlwall et al., 2004, 2006; Shorttle et al., 2014 and references therein).

View in article

Sims, K.W.W., Maclennan, J., Blichert-Toft, J., Mervine, E.M., Blusztajn, J., Grönvold, K. (2013) Short length scale mantle heterogeneity beneath Iceland probed by glacial modulation of melting. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 379, 146–157.

Show in context

Show in context Similar heterogeneous melting models have been described in the literature but, unlike those presented here, the melting behaviours of the different components were arbitrarily chosen (e.g., Ito and Mahoney, 2005; Stracke and Bourdon, 2009; Waters et al., 2011), the F versus T relationships were calculated with pMELTS (e.g., Rudge et al., 2013; Sims et al., 2013) that strongly overestimates the size of melting interval of mantle lithologies and especially pyroxenites, by both overestimating the liquidus temperature and underestimating the solidus temperature (Lambart et al., 2016), and/or the thermal interactions between components were not taken into account (e.g., Koornneef et al., 2012).

View in article

This is only possible if the enriched component has a lower solidus temperature compared to the depleted component, in agreement with Sims et al. (2013).

View in article

Sobolev, A.V., Hofmann, A.W., Kuzmin, D.V., Yaxley, G.M., Arndt, N.T., Chung, S.L., Danyushevsky, L.V., Elliott, T., Frey, F.A., Garcia, M.O., Gurenko, A.A., Kamenetsky, V.S., Kerr, A.C., Krivolutskaya, N.A., Matvienkov, V.V., Nikogosian, I.K., Rocholl, A., Sigurdsson, I.A., Sushchevskaya, N.M., Teklay, M. (2007) The amount of recycled crust in sources of mantle-derived melts. Science 316, 412–417.

Show in context

Show in context It is widely accepted that the compositional spectrum of Icelandic lavas requires the presence of at least two components in the mantle source (e.g., Thirlwall et al., 2004, 2006; Sobolev et al., 2007; Brown and Lesher, 2014).

View in article

However, these hybrid lithologies could be formed either by solid-state reaction (i.e. homogeneous mixing and phase equilibration between the solid recycled crust and the solid peridotite) or by melt-rock reaction, in which melts derived from the recycled crust react with the peridotite to form an olivine-free secondary pyroxenite, such as Px-1 (Sobolev et al., 2007).

View in article

Stracke, A., Bourdon, B. (2009) The importance of melt extraction for tracing mantle heterogeneity. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 73, 218–238.

Show in context

Show in context Similar heterogeneous melting models have been described in the literature but, unlike those presented here, the melting behaviours of the different components were arbitrarily chosen (e.g., Ito and Mahoney, 2005; Stracke and Bourdon, 2009; Waters et al., 2011), the F versus T relationships were calculated with pMELTS (e.g., Rudge et al., 2013; Sims et al., 2013) that strongly overestimates the size of melting interval of mantle lithologies and especially pyroxenites, by both overestimating the liquidus temperature and underestimating the solidus temperature (Lambart et al., 2016), and/or the thermal interactions between components were not taken into account (e.g., Koornneef et al., 2012).

View in article

Stracke and Bourdon (2009) demonstrated that trace element ratios involving a moderately incompatible element (e.g., La/Sm, La/Yb, Hf/Yb) are dominantly influenced by the melting process.

View in article

Calculations show that the trace element – isotope systematics are mostly controlled by the pressure difference between the onset of melting of the lithologies present in the source (Stracke and Bourdon, 2009).

View in article

It was shown in the preceding section that (1) the compositional variability of Icelandic basalt requires at least two different mantle components with different radiogenic isotopic compositions, (2) the most radiogenic component should have the lowest solidus temperature (as in G2- or KG1-configurations), and equally importantly (3) the pooled melts need to be extracted at different depths along the adiabatic path, in agreement with the conclusions of Stracke and Bourdon (2009).

View in article

Thirlwall, M.F., Gee, M.A.M., Taylor, R.N., Murton, B.J. (2004) Mantle components in Iceland and adjacent ridges investigated using double-spike Pb isotope ratios. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 68, 361–386.

Show in context

Show in context It is widely accepted that the compositional spectrum of Icelandic lavas requires the presence of at least two components in the mantle source (e.g., Thirlwall et al., 2004, 2006; Sobolev et al., 2007; Brown and Lesher, 2014).

View in article

In fact, unradiogenic Pb isotopic compositions, Nd and Hf isotope systems and trace element systematics of Icelandic basalts have all been used to validate the presence of a distinct depleted endmember for the Iceland plume (e.g., Thirlwall et al., 2004, 2006; Shorttle et al., 2014 and references therein).

View in article

Thirlwall, M.F., Gee, M.A.M., Lowry, D., Mattey, D.P., Murton, B.J., Taylor, R.N. (2006) Low δ18O in the Icelandic mantle and its origins: evidence from Reykjanes ridge and Icelandic lavas. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 70, 993–1019.

Show in context

Show in context It is widely accepted that the compositional spectrum of Icelandic lavas requires the presence of at least two components in the mantle source (e.g., Thirlwall et al., 2004, 2006; Sobolev et al., 2007; Brown and Lesher, 2014).

View in article

In fact, unradiogenic Pb isotopic compositions, Nd and Hf isotope systems and trace element systematics of Icelandic basalts have all been used to validate the presence of a distinct depleted endmember for the Iceland plume (e.g., Thirlwall et al., 2004, 2006; Shorttle et al., 2014 and references therein).

View in article

Waters, C.L., Sims, K.W.W., Perfit, M.R., Blichert-Toft, J., Blusztajn, J. (2011) Perspective on the Genesis of E-MORB from Chemical and Isotopic Heterogeneity at 9-10°N East Pacific Rise. Journal of Petrology 52, 565–602.

Show in context

Show in context Similar heterogeneous melting models have been described in the literature but, unlike those presented here, the melting behaviours of the different components were arbitrarily chosen (e.g., Ito and Mahoney, 2005; Stracke and Bourdon, 2009; Waters et al., 2011), the F versus T relationships were calculated with pMELTS (e.g., Rudge et al., 2013; Sims et al., 2013) that strongly overestimates the size of melting interval of mantle lithologies and especially pyroxenites, by both overestimating the liquidus temperature and underestimating the solidus temperature (Lambart et al., 2016), and/or the thermal interactions between components were not taken into account (e.g., Koornneef et al., 2012).

View in article

top

Supplementary Information

Methods and Extended Discussion

Melting and melt mixing of a heterogeneous source

It is widely accepted that MORBs are mixes of melts from all depths in the melting column (e.g., Klein and Langmuir, 1987; Langmuir et al., 1992). In these calculations, I assumed that this dynamic model can be applied to the rift zones in Iceland where the melting regime is similar to the melting regime beneath mid-ocean ridges (Brown and Lesher, 2014, Shorttle et al., 2014). In fact, correlations between trace element and isotope compositions in Icelandic basalts (Fig. 2e-f in the main text) indicate that the melting process and sampling of source heterogeneity are intrinsically related. In addition, melt extraction without continuous equilibration with the ambient mantle is required to explain the compositional variability observed in single flow (Maclennan et al., 2003) and the preserved U-series disequilibria (Koornneef et al., 2012a and references therein). High-porosity melt channels are good candidates for promoting melt mixing between the two source components while providing an efficient melt extraction process (Kelemen et al., 1997). Moreover, Weatherley and Katz (2016) recently suggested that channelised flow can be a consequence of melting of a heterogeneous mantle.

Methods

Melt-PX calculations. I used Melt-PX (Lambart et al., 2016) to model the decompression melting of the three mantle configurations. In this model, melting and decompression are assumed to occur isentropically in a passive triangular melting regime (White et al., 1992), the various lithologies are in thermal equilibrium but chemically isolated, and melts from each lithology are mixed continuously along the melting column. Calculations have been performed for TP = 1480 °C and with an initial clinopyroxene mode in the peridotite of 15 %. At this TP, along an adiabatic decompression path, G2 starts to melt at much higher pressure than the fertile peridotite and stops soon after the peridotite solidus is crossed (Fig. S-1). This phenomenon occurs because, once the peridotite solidus is crossed, too much latent heat is consumed by the large fraction of peridotite undergoing melting for the G2 residue to stay above its solidus during further ascent (Phipps Morgan, 2001; Lambart et al., 2016). In other words, G2 stops melting because, following the onset of KLB-1 melting, the mantle moves below (or parallel to) G2's melt depleted solidus. KG1 starts to melt just before the peridotite and continues to melt with the peridotite (Fig. S-2). Finally, KG2 starts to melt after the fertile peridotite (Fig. S-3). Calculations were stopped when the mantle column had upwelled to the base of the crust, i.e. when the pressure at the base of the crust, Pc = P.

Figure S-1 Results of the Melt-PX calculations for the G2-configuration at a potential temperature of 1480 °C. (a) Pressure-temperature path for the column of mantle undergoing isentropic decompression (black line). The solid red and the dashed green lines are the solidi of G2 and KLB-1, respectively. (b-c) Extent of the melting (b) and melt productivity (c) of G2 (solid red line) and KLB-1 (dashed green line) along the adiabatic path.

Figure S-2 Results of the Melt-PX calculations for the KG1-configuration at a potential temperature of 1480 °C. (a) Pressure-temperature path for the column of mantle undergoing isentropic decompression (black line). The solid orange and the dashed green lines are the solidi of KG1 and KLB-1, respectively. (b-c) Extent of the melting (b) and melt productivity (c) of KG1 (solid orange line) and KLB-1 (dashed green line) along the adiabatic path.

Figure S-3 Results of the Melt-PX calculations for the KG2-configuration at a potential temperature of 1480 °C. (a) Pressure-temperature path for the column of mantle undergoing isentropic decompression (black line). The solid blue and the dashed green lines are the solidi of KG1 and KLB-1, respectively. (b-c) Extent of the melting (b) and melt productivity (c) of KG1 (solid blue line) and KLB-1 (dashed green line) along the adiabatic path.

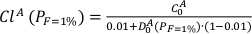

pMELTS calculations. pMELTS (Ghiorso et al., 2002) is not suitable for estimating pyroxenite melt fractions as a function of P and T, but can provide reasonable estimations of the phase assemblage at each pressure step (Lambart et al., 2016). Hence, I used pMELTS to calculate the residual phase assemblages along the adiabatic decompression path calculated with Melt-PX (Lambart et al., 2016). At each P-F condition, I calculated the residual phase assemblage using the isobaric batch melting mode. For each component, calculations start at PF = 1% and are repeated every 0.01 GPa pressure interval. Note that while trace element calculations attempt to simulate a near-fractional melting through a series of iterative batch melting calculations, the major element composition of each component is kept constant in the calculations. However, the melting regime (fractional vs. batch) does not significantly affect the phase assemblage (Fig. S-4), and consequently will not affect significantly the trace element composition of the melt at each pressure increment. To perform the pMELTS calculations, I took the same choices and constraints as Lambart et al. (2016): (1) calculations were made at ƒO2 = FMQ - 1 (i.e. the fayalite-magnetite-quartz buffer minus one log unit), (2) I used the corrected version of the garnet model (Berman and Koziol, 1991) and (3) Cr2O3 and MnO were not included in the calculations.

Figure S-4 Evolution of the solid phase modes for the composition KLB-1 (Hirose and Kushiro, 1993) as a function of the proportion of melt during batch melting (solid lines) and continuous melting (dashed lines). The threshold for melt segregation in the continuous melting calculations is 1 %. Calculations were performed at 1 GPa using the thermodynamic model pMELTS (Ghiorso et al., 2002) and the alphaMELTS front-end (Smith and Asimow, 2005). Olivine: red; orthopyroxene (opx): orange; clinopyroxene (cpx): blue; spinel (sp): green.

Trace element calculations. For the recycled component G2, I used the trace element and isotopic composition of the recycled component in Koornneef et al. (2012b). The trace element composition corresponds to a mix between E-MORB 1312-47 (Sun et al., 2008) and average gabbro 735B (Hart et al., 1999) in a 1:1 ratio. The isotopic composition corresponds to a 2 Ga recycled oceanic crust altered by sea water and modified during the subduction process by dehydration (Stracke et al., 2003). The peridotite component has the trace element composition of the depleted DMM in Workman and Hart (2005) and the isotopic composition of the Extreme D-MORB in Salters and Stracke (2004).

Continuous melting is simulated by incremental ‘dynamic melting’; that is, by small steps of batch melting while keeping a small melt fraction residual.

(1) Incremental melts produced by each lithology.

I assumed that the melt formed at F = 1 % is in equilibrium with the residual solid phases.

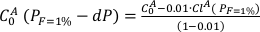

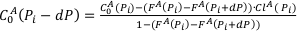

Eq. S-1

C0A is the initial bulk trace element composition of the lithology A. D0A is the bulk partition coefficient and is calculated using the set of partition coefficients provided in alphaMELTS (Smith and Asimow, 2005) and the phase assemblage obtained with pMELTS at PF=1% - F = 1 % condition along the adiabatic decompression path previously calculated with Melt-PX (Lambart et al., 2016). The primitive mantle normalised trace element patterns for the first-degree melts produced in the three configurations are plotted in Figure S-5.

Then, the bulk trace element composition is recalculated by extracting the first-degree melt.

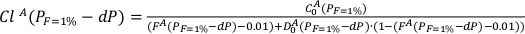

Eq. S-2

These operations are repeated for the next pressure increment -dP:

Eq. S-3

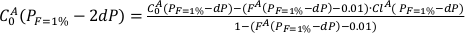

Eq. S-4

FA is the melting degree of the lithology A. The new D0A is calculated using the phase assemblage obtained with pMELTS at (PF=1% + dP) and FA(PF=1% + dP).

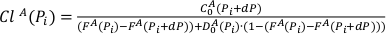

These expressions can be generalised for a given pressure Pi:

Eq. S-5

Eq. S-6

The pressure increment in the calculation was dP = 0.01 GPa.

Mineral–melt partition coefficients depend on the melt and mineral compositions (e.g., Nielsen, 1988; Blundy and Wood, 1991), pressure and temperature conditions (e.g., Taura et al., 1998), oxygen fugacity (Laubier et al., 2014), and consequently might differ for KLB-1, KG1, KG2 and G2 melts and from partition coefficients from Smith and Asimow (2005). However, the residual modal mineralogy exerts the major control on the bulk partition coefficient and consequently on the trace element composition of the melt. Because the residual mineralogy is adapted for each lithology during melting using pMELTS modelling, the use of constant partition coefficients in these calculations is not expected to introduce large errors.

(2) Accumulated melt.

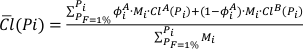

Compositions of the accumulated melts are calculated for complete mixing of melts from the two mantle components integrated over the melting column. At Pi, the composition of the aggregated melt is:

Eq. S-7

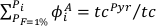

with ΦAi , the proportion of the oceanic crust formed at Pi and derived from lithology A such as:

Eq. S-8

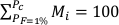

with tc the thickness of the generated oceanic crust, tcPyr, the proportion of the crust derived from the pyroxenite component, and Mi, the proportion of oceanic crust formed between Pi and Pi + dP such as:

Eq. S-9

Figure S-5 Primitive mantle (PM; Sun and McDonough, 1989) normalised trace element patterns of the first degree melts (dashed lines) and the last accumulated melts produced at the base of the crust (solid lines) in G2- (red), KG1- (orange) and KG2- (blue) configurations.

Figure S-6 Incompatible trace element ratios of the calculated accumulated melts as functions of the pressure in the three configurations (colour code is the same as in Fig. S-5). Solid lines represent the formation pressure of the first degree melt from the enriched mantle component (G2, KG1 or KG2) and dashed lines represent the formation pressure of the first degree melt from the peridotite component in the corresponding mantle configuration. The grey areas represent the range of compositional ratios in Icelandic basalts with MgO contents between 9.5 and 17 wt. % from the Northern Volcanic zone, the Reykjanes Peninsula, the Snaefellsnes area and the South Eastern Volcanic Zone (GEOROC).

Figure S-7 Comparison of SiO2 (a) and MgO (b) contents of the melt produced by G2 (red circles; Pertermann and Hirschmann, 2003), KG1 and KG2 (orange and blue squares, respectively; Kogiso et al., 1998), Px-1 (black-diamond; Sobolev et al., 2007), and KLB-1 (green triangles; Hirose and Kushiro, 1993) at 3 GPa.

Figure S-8 Near-solidus curves (T5%) (a) and melting curves at 3 GPa (b) calculated using Melt-PX (Lambart et al., 2016) for Px-1 (black; Sobolev et al., 2007) and KG1 (orange; Kogiso et al., 1998) compositions.

Olivine nickel content modelling

Contrary to the model proposed here, Herzberg et al. (2016) emphasised the lack of lithological variability in the Icelandic source based on olivine chemistry and in particular, on transition metal contents in olivine. Part of the disagreement is because a false dichotomy has been set up in which mantle lithologies are divided into two categories which are olivine-free lithologies (such as Px-1 or G2) and “normal” peridotite.

To test my model, I calculated the Fo and Ni contents of olivine produced during the low-pressure fractional crystallisation of the aggregated melts produced by the KG1-configuration and compared the results to Ni and Fo contents of olivines from Icelandic basalts (Fig. S-9; Sobolev et al., 2007; Shorttle and Maclennan, 2011).

Figure S-9 Ni content of olivines from Icelandic basalts (large dark grey circles, Sobolev et al., 2007; large light grey circles, Shorttle and Maclennan, 2011). The lines are modelled olivine compositions produced by fractionally crystallising aggregated parental melts sampled at 4, 1.5 and 0.6 GPa along the adiabatic path in the KG1-configuration. The melts chosen for modelling are reported in Table S-3. Parental melts then had equilibrium olivine fractionally extracted from them at 1 bar using olivine compositions calculated with PRIMELT2.xls (Herzberg and Asimow, 2008) and according the Ni partitioning model of Matzen et al. (2017). Data from Sobolev et al. (2007) in other locations are also shown for comparison (small dark grey circles). See text for details of calculations.

The starting Ni content of KLB-1 was taken from Hirose and Kushiro (1993). The starting Ni content of G2 was taken from Sobolev et al. (2005). KG1 Ni content was calculated using the 1:1 proportion between KLB‐1 and G2 (Table S-1).

Table S-1 Majora, traceb element and isotopic compositions of G2, KLB-1, KG1, KG2 and Bulk1.

| G2c | KLB-1d | KG1e | KG2e | Bulk1f | |

| SiO2 | 50.05 | 44.48 | 47 | 46.2 | 45.04 |

| TiO2 | 1.97 | 0.16 | 0.78 | 0.57 | 0.34 |

| Al2O3 | 15.76 | 3.59 | 9.75 | 7.69 | 4.81 |

| FeO | 9.35 | 8.1 | 9.77 | 9.22 | 8.23 |

| MnO | 0.17 | 0.12 | 0 | 0 | 0.13 |

| MgO | 7.9 | 39.22 | 23.6 | 28.8 | 36.09 |

| CaO | 11.74 | 3.44 | 7.35 | 6.05 | 4.27 |

| Na2O | 3.04 | 0.3 | 1.52 | 1.11 | 0.57 |

| K2O | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.02 |

| Ni | 200 | 1964 | 1082 | 1376 | 1788 |

| Rb | 1.188 | 0.02 | 0.604 | 0.409 | 0.137 |

| Ba | 19.32 | 0.227 | 9.774 | 6.591 | 2.136 |

| Th | 0.135 | 0.004 | 0.07 | 0.048 | 0.017 |

| U | 0.046 | 0.0018 | 0.0239 | 0.0165 | 0.0062 |

| Nb | 6.13 | 0.0864 | 3.1082 | 2.1009 | 0.6908 |

| Cla | 2.695 | 0.134 | 1.415 | 0.988 | 0.39 |

| Ce | 8.161 | 0.421 | 4.291 | 3.001 | 1.195 |

| Sr | 98.11 | 6.092 | 52.101 | 36.765 | 15.294 |

| Nd | 8.375 | 0.483 | 4.429 | 3.114 | 1.272 |

| Zr | 65 | 4.269 | 34.635 | 24.513 | 10.342 |

| Sm | 2.3 | 0.21 | 1.26 | 0.91 | 0.42 |

| Hf | 1.709 | 0.127 | 0.918 | 0.654 | 0.285 |

| Eu | 1.055 | 0.086 | 0.571 | 0.409 | 0.183 |

| Gd | 3.7 | 0.324 | 2.012 | 1.449 | 0.662 |

| Tb | 0.7 | 0.064 | 0.382 | 0.276 | 0.128 |

| Dy | 4.4 | 0.471 | 2.436 | 1.781 | 0.864 |

| Ho | 1.15 | 0.108 | 0.629 | 0.455 | 0.212 |

| Y | 24.72 | 3.129 | 13.925 | 10.326 | 5.288 |

| Er | 2.653 | 0.329 | 1.491 | 1.104 | 0.561 |

| Yb | 3.4 | 0.348 | 1.874 | 1.365 | 0.653 |

| Lu | 0.371 | 0.056 | 0.214 | 0.161 | 0.088 |

| 143Nd/144Nd | 0.5127 | 0.5134 | 0.512738 | 0.512819 | 0.512939 |

| 87Sr/86Sr | 0.7037 | 0.702 | 0.703636 | 0.703493 | 0.703306 |

a in wt. %

b in ppm

c G2: Major element composition is from Perterman and Hirschmann (2003); Ni content is from Sobolev et al. (2007); trace element composition corresponds to the composition K11 from Koorneff et al. (2012b); isotopic composition corresponds to a 2 Ga recycled oceanic crust altered by sea water and modified during the subduction process by dehydration using the model of Stracke et al. (2003).

d KLB-1: Major element composition and Ni content are from Hirose and Kushiro (1993); trace element composition is DDMM from Workman and Hart (2005); isotopic composition corresponds to the extreme D-MORB from Salters and Stracke (2004).

e KG1 and KG2: Major element compositions are from Kogiso et al. (1998); Ni content and trace element and isotopic compositions calculated as 1G2:1KLB-1 and 1G2:2KLB-1, respectively.

f Bulk1: Major, trace element and isotopic compositions are calculated as 1G2:9KLB-1.

Because the trace element - isotope systematics of Icelandic basalts imply that melts are sampled at various depths along the melting column, I did calculations for three different melt compositions: the aggregated melt sampled at 4 GPa, where only KG1 is melting, the aggregated melt sampled at 1.5 GPa, and the aggregated melt sampled at the base of the crust, 0.6 GPa, where melting is assumed to stop. Ni contents of the aggregated melts were calculated in three steps: (1) I used Melt-PX to calculate the melting degree of KG1 and KLB-1 at 4, 1.5 and 0.6 GPa in the KG1-configuration (Table S-2) and I used pMELTS to calculate the residual mode for each lithology (Table S-2) at the corresponding P-F conditions (see above for details on Melt-PX and pMELTS calculations). (2) Because the Ni partition coefficient between olivine and melt is a function of temperature and/or pressure (Matzen et al., 2013), in addition to composition (e.g., Leeman and Lindstrom 1978; Beattie, 1993; Putirka et al. 2011; Matzen et al., 2017), I used the Ni partitioning model of Matzen et al. (2017) to calculate the Ni content in melts derived from each lithology at the corresponding pressure. This model allows me to separate the effects of temperature from composition. Liquidus temperature and olivine composition in equilibrium with each melt (required to use Matzen et al.’s model) were calculated with the PRIMELT2.xls software (Herzberg and Asimow, 2008). Melts were run through PRIMELT2.xls assuming a major element composition of the mantle source equal to Bulk-1 (Table S-1). The oxidation state of the source was fixed at Fe2+/∑Fe and Fe2O3 ratios of 0.89 and 0.5, respectively. The composition of the KG1- and KLB-1 derived melts used in the calculations are reported in Table S-2. (3) I calculated the Ni (and major element) contents in the aggregated melts according the contribution of each melt to the bulk magmatic productivity (i.e. Eq. S-8). Compositions of the aggregated melts used in the calculations are reported in Table S-3.

Table S-2 Melt compositions and parameters used in olivine fractionation modelling.

| P | 4 GPa | 1.5 GPa | 0.6 GPa | ||

| KG1a | KG1b | KLB-1c | KG1b | KLB-1d | |

| SiO2 | 43 | 49.9 | 48.6 | 49.9 | 50.7 |

| TiO2 | 3.32 | 0.45 | 1.16 | 0.45 | 0.42 |

| Al2O3 | 15.5 | 13.8 | 14.3 | 13.8 | 14.6 |

| FeO | 11.5 | 7.92 | 9.19 | 7.92 | 7.64 |

| MgO | 14.2 | 15.7 | 13.5 | 15.7 | 13.4 |

| CaO | 7.82 | 10.7 | 10.2 | 10.7 | 11.2 |

| Na2O | 3.68 | 1.04 | 2.65 | 1.04 | 1.5 |

| K2O | 0.87 | 0.04 | 0.21 | 0.04 | 0.19 |

| F e | 2 | 48.5 | 16.4 | 71 | 23 |

| Xol f | 20.8 | 11.5 | 59.5 | 29 | 70.7 |

| Xopxf | 1.8 | 17.5 | 16.6 | 0 | 5.5 |

| Xcpxf | 47.2 | 21.4 | 7 | 0 | 0.6 |

| Xgtf | 29.9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Xspf | 0.3 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.2 |

| TLg | 1785 | 1712 | 1662 | 1667 | 1616 |

| Fog | 88.3 | 92 | 90.1 | 92.3 | 91.5 |

| DNiol/liq h | 4.25 | 4.61 | 5.58 | 4.96 | 6.19 |

| Ni in melti | 636 | 657 | 498 | 504 | 415 |

a Major-element composition used to model the KG1-derived melt at 4 GPa (glass in run #KH22 in Kogiso et al., 1998).

b Major-element composition used to model the KG1-derived melt at 1.5 GPa and 0.6 GPa. GPa (glass in run #KH43 in Kogiso et al., 1998).

d Major-element composition used to model the KBL-1-derived melt at 0.6 GPa (glass in run #14 in Hirose and Kushiro, 1993).

e Melting degree calculated with Melt-PX at the corresponding pressure along the adiabatic path.

f Mode of the residual solid phases of each lithology at the corresponding pressure along the adiabatic path.

g Calculated liquidus temperature (TL) in kelvin and forsterite content (Fo) of the olivine in equilibrium with each liquid at the corresponding pressure (Herzberg and Asimow, 2008).

h Calculated DNiol/liq using the Ni partitioning model from Matsen et al. (2017).

i Ni content (in ppm) in the melts. Contents in melts from KG1 and KLB1 are calcuated using the modelled DNiol/liq, and using Ni partitioning callibration for orthopyroxene-melt (Beattie et al., 1991), olivine-garnet (Canil, 1999) and orthopyroxene-clinopyroxene (Seitz et al., 1999).

Table S-3 Compositions of the aggregated parental melt (APM) sampled at 4, 1.5 and 0.6 GPa and of the olivine in equilibrium at 1 bar.

| 4 GPa | 1.5 GPa | 0.6 GPa | |

| tcpyr/tc a | 1 | 0.54 | 0.53 |

| SiO2 (wt. %) | 43 | 49.2 | 49.5 |

| TiO2 (wt. %) | 3.32 | 0.83 | 0.84 |

| Al2O3 (wt. %) | 15.5 | 14.1 | 14.4 |

| FeO (wt. %) | 11.5 | 8.61 | 8.52 |

| MgO (wt. %) | 14.2 | 14.5 | 13.5 |

| CaO (wt. %) | 7.82 | 10.4 | 10.6 |

| Na2O (wt. %) | 3.68 | 1.9 | 2.16 |

| K2O (wt. %) | 0.87 | 0.13 | 0.2 |

| Ni (ppm) | 636 | 571 | 468 |

| TLb | 1601 | 1609 | 1586 |

| Fob | 90 | 91.6 | 91.1 |

| DNiol/liq c | 5.72 | 5.76 | 6.44 |

| Ni in ol d | 3641 | 3288 | 3016 |

a Contribution of the melt derived from KG1 to the volume of magma produced.

b Calculated liquidus temperature (TL) and forsterite content (Fo) of the olivine in equilibrium with APM at 1bar (Herzberg and Asimow, 2008).

c DNiol/liq at 1 bar using Matzen et al. (2017) model.

d Ni content (in ppm) in olivine in equilibrium with APM at 1 bar.

Ni contents of the olivine that fractionates from the aggregated magmas at 1 bar were estimated using DNiol/liq at 1 bar according Matzen et al.’s (2017) model (Fig. S-9); liquidus temperature of the aggregated melts and olivine composition in equilibrium at 1 bar were calculated with PRIMELTS2.xls using the same mantle source composition and oxidation state as above.

Most of the olivine Ni variation reported by Sobolev et al. (2007) and Shorttle and Maclennan (2011) can be explained by varying the sampling pressure of the aggregated melts in the melting column, with the compositions richest in Ni sampled at the highest pressure where the contribution of KG1 is the largest. Similar results were obtained by Shortlle and Maclennan (2011) using KG2- and KBL-1-derived melts. The authors also showed that fractionation of cpx and plagioclase in addition to olivine when melts reach 9 wt. % MgO could also explained the olivine compositions richest in Ni. However, the melting behaviours of the different lithologies present in the source were not taken into account. In particular, because KG2 starts to melt after the peridotite along the adiabatic path (Fig. S-3), the contribution of this lithology to the magma production cannot explain the trace element – isotope systematics of Icelandic basalts (Fig. 2e-f in the main text). In addition, calculations presented here consider the effect of pressure on Ni partitioning and support a model in which aggregated melts are collected at various pressures of the melting column.

Supplementary Information References