Primary spinel + chlorite inclusions in mantle garnet formed at ultrahigh-pressure

Affiliations | Corresponding Author | Cite as | Funding information- Share this article

Article views:6,370Cumulative count of HTML views and PDF downloads.

- Download Citation

- Rights & Permissions

Abstract

Figures and Tables

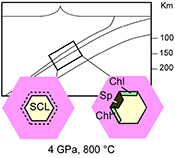

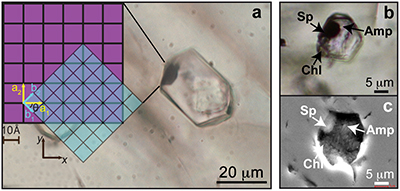

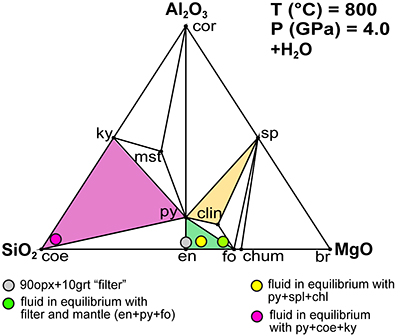

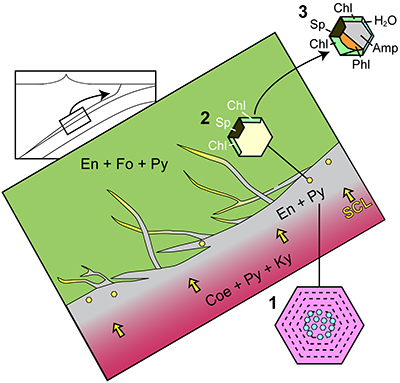

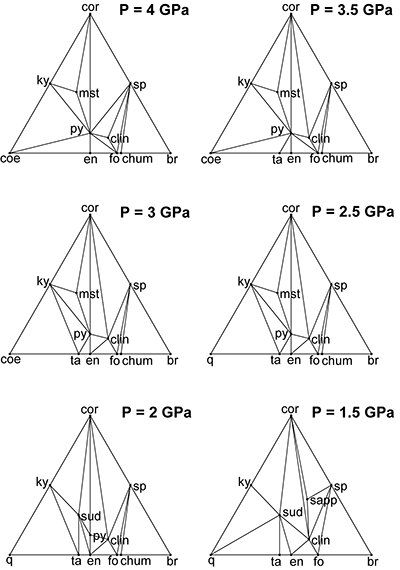

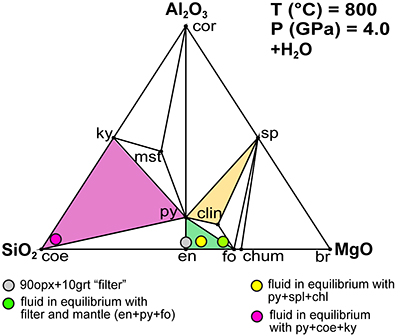

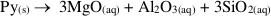

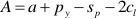

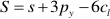

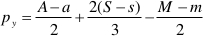

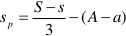

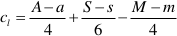

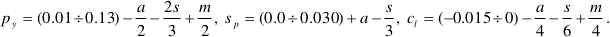

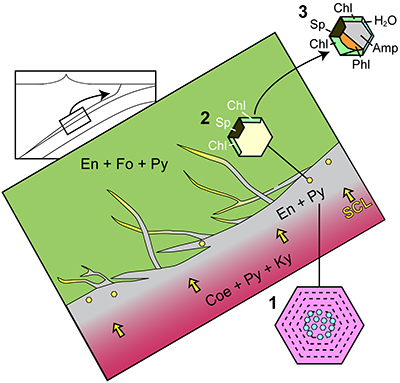

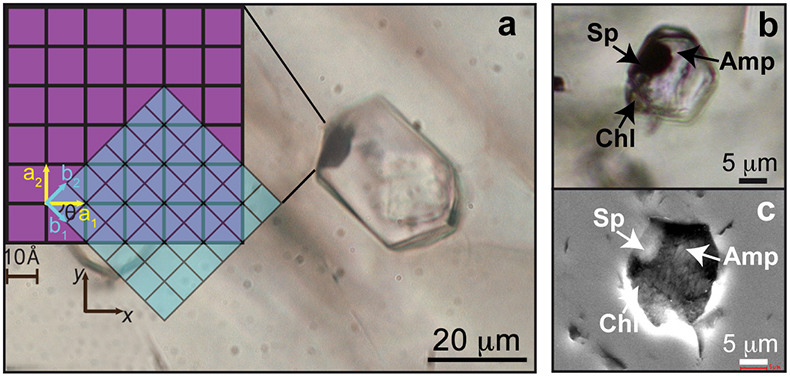

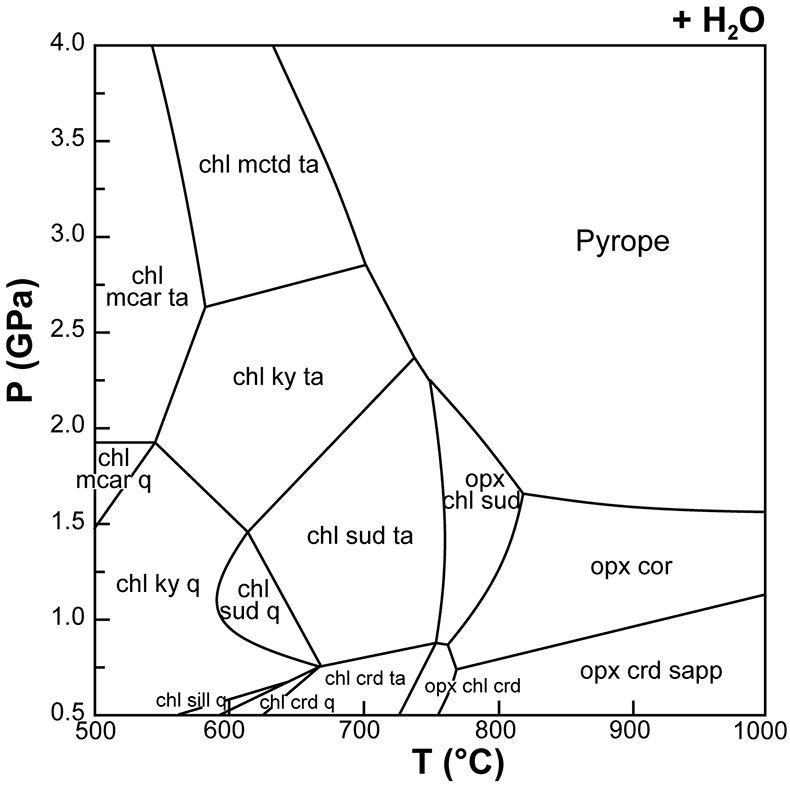

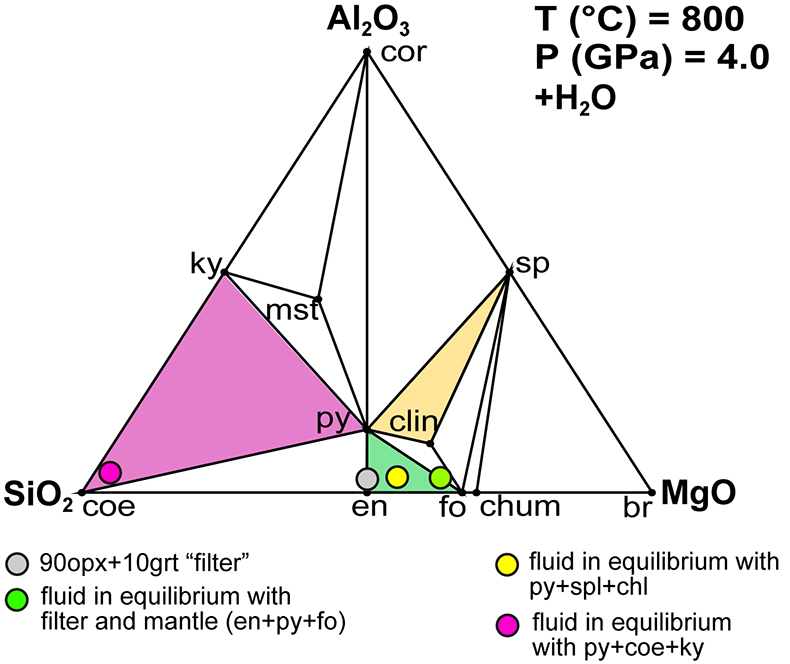

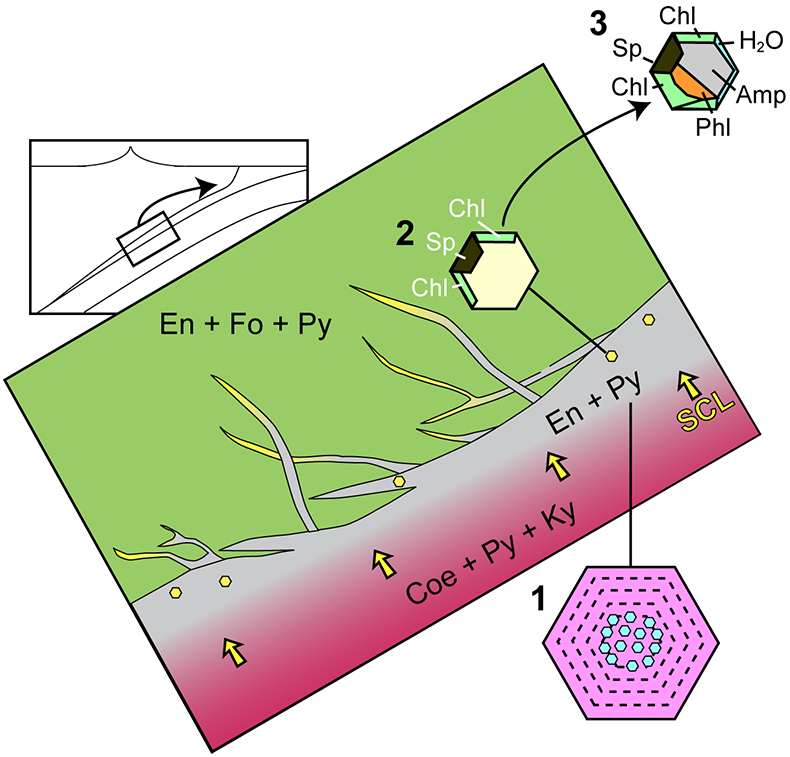

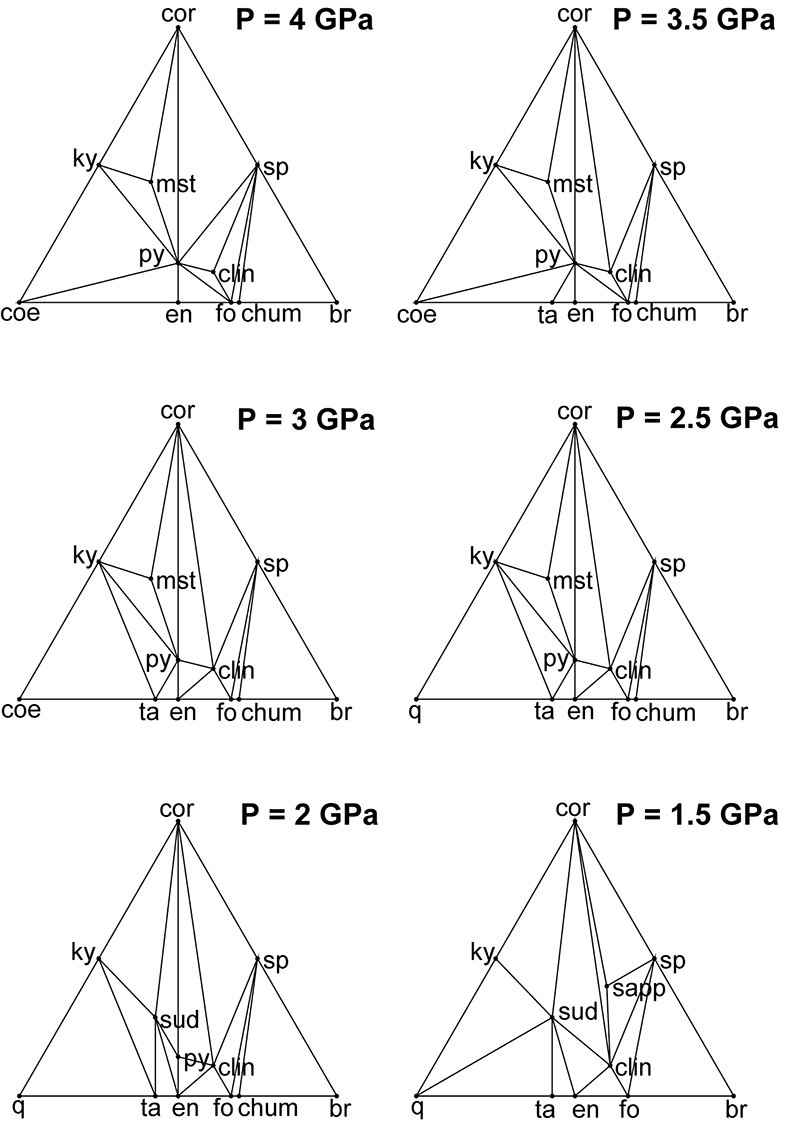

Figure 1 (a) Photomicrograph of a multiphase solid inclusion in metasomatic garnet from Maowu Ultramafic Complex (Dabie Shan, China). Inset represents the relative orientation of the spinel {100} surface lattice (light blue) with respect to the garnet {100} surface lattice (violet) for the coincidence at θ = −45° (from Malaspina et al., 2015). (b) and (c) Negative-crystal shaped multiphase solid inclusion (plane polarised transmitted light and Secondary Electron image) with evident microstructural relations between spinel, chlorite and amphibole (gedrite). |  Figure 2 Isochemical P-T section in the MASH system showing the predicted mineral assemblages calculated with Perple_X software package (Connolly, 1990) for a bulk composition corresponding to pyrope [MgO (3 mol) - SiO2 (3 mol) - Al2O3 (1 mol)] + excess H2O. Mineral abbreviations: chl = chlorite, mctd = Mg-clorithoid, ta = talc, mcar = Mg-carpholite, ky = kyanite, q = quartz, opx = orthopyroxene, sud = sudoite, cor = corundum, sill = sillimanite, crd = cordierite, sapp = sapphirine. |  Figure 3 Chemography of the MgO-Al2O3-SiO2-H2O system at 4 GPa and 800 °C, projected from water, showing the stable assemblages coe-ky-py (purple field), py-en-fo (green), and py-sp-clin (yellow). Experimental equilibrium slab fluid compositions and mantle fluid compositions are indicated by purple and green dots, respectively. Calculated compositions of a fluid in equilibrium with py-sp-clin assemblage is indicated by a yellow dot. The bulk composition of the orthopyroxenite containing multiphase inclusions in garnet is indicated by a grey dot. Mineral abbreviations same as in Figure 2 and coe = coesite, mst = Mg-staurolite, py = pyrope, en = enstatite, clin = clinochlore, sp = spinel, fo = forsterite, chum = clinohumite, br = brucite. |  Figure 4 Schematic cartoon showing aqueous fluid entrapped by growing metasomatic garnet (1) after the interaction of slab-derived supercritical liquid (SCL) and the supra-subduction mantle peridotite forming garnet orthopyroxenite (grey layer and veins). Light blue hexagons represent primary aqueous inclusions in pyrope. Garnet/fluid interaction yields a dissolution and precipitation process that triggers epitaxial nucleation of spinel and chlorite during garnet growing at UHP (2). Subsequent post-entrapment crystallisation of the other hydrous phases such as gedrite, phlogopite, pargasite and talc during the retrograde P-T path (3) leaves an eventual residue of water solution (light blue rim). Modified after Malaspina et al. (2017). |

| Figure 1 | Figure 2 | Figure 3 | Figure 4 |

Supplementary Figures and Tables

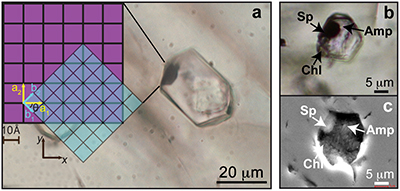

Table S-1 MgO, Al2O3 and SiO2 molalities of aqueous solutions in equilibrium with different assemblages, calculated using the aqueous speciation-solubility code EQ3 adapted to include equilibrium constants calculated with the Deep Earth Water (DEW) model. |  Figure S-1 Compatibility diagrams of the water-saturated MgO-Al2O3-SiO2-H2O system at 800 °C and 1.5–4 GPa, projected from water, showing that the stable assemblage pyrope-spinel-clinochlore occurs only at UHP conditions. Mineral abbreviations same as Figures 2 and 3 of the manuscript. |

| Table S-1 | Figure S-1 |

top

Introduction

Primary inclusions (fluid or solid multiphase) in mantle minerals represent the remnant of the fluid phase produced by dehydration reactions in the subducted slab and subsequently equilibrated with the overlying supra-subduction mantle peridotites. Natural and experimental studies demonstrated that saline aqueous inclusions with variable solute load prevail in high pressure (HP) rocks (Scambelluri and Philippot, 2001

Scambelluri, M., Philippot, P. (2001) Deep fluids in subduction zones. Lithos 55, 213–227.

; Touret, 2001Touret, J.L. (2001) Fluids in metamorphic rocks. Lithos 55, 1–25.

), whereas multiphase solid inclusions in some ultrahigh pressure (UHP) rocks have been attributed to silicate-rich fluids or hydrous melts at supercritical conditions, namely supercritical liquids (Bureau and Keppler, 1999Bureau, H., Keppler, H. (1999) Complete miscibility between silicate melts and hydrous fluids in the upper mantle: experimental evidence and geochemical implications. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 165, 187–196.

; Stöckhert et al., 2001Stöckhert, B., Duyster, J., Trepmann, C., Massonne, H., Sto, B. (2001) Microdiamond daughter crystals precipitated from supercritical COH + silicate fluids included in garnet, Erzgebirge, Germany. Geology 29, 391–394.

; Carswell and van Roermund, 2005Carswell, D.A., van Roermund, H.L.M. (2005) On multi-phase mineral inclusions associated with microdiamond formation in mantle-derived peridotite lens at Bardane on Fjørtoft, west Norway. European Journal of Mineralogy 17, 31–42.

; Ferrando et al., 2005Ferrando, S., Frezzotti, M.L., Dallai, L., Compagnoni, R. (2005) Multiphase solid inclusions in UHP rocks (Su-Lu, China): Remnants of supercritical silicate-rich aqueous fluids released during continental subduction. Chemical Geology 223, 68–81.

; Korsakov and Hermann, 2006Korsakov, A.V., Hermann, J. (2006) Silicate and carbonate melt inclusions associated with diamonds in deeply subducted carbonate rocks. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 241, 104–118.

; Malaspina et al., 2006Malaspina, N., Hermann, J., Scambelluri, M., Compagnoni, R. (2006) Polyphase inclusions in garnet–orthopyroxenite (Dabie Shan, China) as monitors for metasomatism and fluid-related trace element transfer in subduction zone peridotite. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 249, 173–187.

). These inclusions are frequently hosted by minerals stable at mantle depths, such as garnet, and show the same textural features as fluid inclusions (Frezzotti and Ferrando, 2015Frezzotti, M.L., Ferrando, S. (2015) The chemical behavior of fluids released during deep subduction based on fluid inclusions. American Mineralogist 100, 352–377.

; Fig. 1). The mineral infillings of the solid multiphase inclusions are generally assumed to have crystallised by a simultaneous precipitation from the solute load of dense supercritical liquids equilibrating with the host rock. Moreover, the occurrence of phases stable at UHP, such as coesite or microdiamond, has long been considered evidence of precipitation from such liquids at pressures above 3 GPa. Here, we demonstrate that even a mineral association characterised by phases usually considered stable at relatively low pressure in mantle systems (e.g., spinel + chlorite), would potentially crystallise at UHP by chemical fluid/host interaction.We will consider as a case study a well-known example of multiphase solid inclusions occurring in the cores of garnets forming orthopyroxenites from the Maowu Ultramafic Complex (Eastern China), interpreted as hybrid rocks resulting from the interaction of previous harzburgites and slab-derived silica-rich liquids (P = 4 GPa, T = 800 °C) at the slab-mantle interface (Malaspina et al., 2006

Malaspina, N., Hermann, J., Scambelluri, M., Compagnoni, R. (2006) Polyphase inclusions in garnet–orthopyroxenite (Dabie Shan, China) as monitors for metasomatism and fluid-related trace element transfer in subduction zone peridotite. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 249, 173–187.

; Chen et al., 2017Chen, Y., Su, B., Chu, Z. (2017) Modification of an ancient subcontinental lithospheric mantle by continental subduction: Insight from the Maowu garnet peridotites in the Dabie UHP belt, eastern China. Lithos 278–281, 54–71.

). These multiphase inclusions have negative crystal shapes and constant volume proportions of the mineral infillings consisting of spinel ± orthopyroxene, and hydrous phases gedrite/pargasite, chlorite, phlogopite, ±talc, ±apatite (Malaspina et al., 2006Malaspina, N., Hermann, J., Scambelluri, M., Compagnoni, R. (2006) Polyphase inclusions in garnet–orthopyroxenite (Dabie Shan, China) as monitors for metasomatism and fluid-related trace element transfer in subduction zone peridotite. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 249, 173–187.

, 2015Malaspina, N., Alvaro, M., Campione, M., Wilhelm, H., Nestola, F. (2015) Dynamics of mineral crystallization from precipitated slab-derived fluid phase: first in situ synchrotron X-ray measurements. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology 169, 26.

; Fig. 1). Some inclusions still preserve liquid water at the interface between mineral infillings and the cavity wall (Malaspina et al., 2017Malaspina, N., Langenhorst, F., Tumiati, S., Campione, M., Frezzotti, M.L., Poli, S. (2017) The redox budget of crust-derived fluid phases at the slab-mantle interface. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 209, 70–84.

). Recently, Malaspina et al. (2015)Malaspina, N., Alvaro, M., Campione, M., Wilhelm, H., Nestola, F. (2015) Dynamics of mineral crystallization from precipitated slab-derived fluid phase: first in situ synchrotron X-ray measurements. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology 169, 26.

demonstrated the epitaxial relationship between spinel and garnet (Fig. 1a), which suggested nucleation of spinel under near-to-equilibrium conditions. On the contrary, hydrous phases (amphiboles, chlorite and ±talc ±phlogopite) nucleate in a non-registered manner and likely under far-from-equilibrium conditions. The epitaxial growth of spinel with respect to garnet and the chlorite rim + water assemblage filling the space between the host garnet and the other inclusion minerals (Malaspina et al., 2017Malaspina, N., Langenhorst, F., Tumiati, S., Campione, M., Frezzotti, M.L., Poli, S. (2017) The redox budget of crust-derived fluid phases at the slab-mantle interface. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 209, 70–84.

), suggest that spinel and chlorite formed at UHP together with the garnet cores. However, spinel should be stable at UHP conditions neither in hydrous peridotites (Niida and Green, 1999Niida, K., Green, D.H. (1999) Stability and chemical composition of pargasitic amphibole in MORB pyrolite under upper mantle conditions. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology 135, 18–40.

), nor in a chemical system characterised by pyrope + H2O, at any P-T range (Fig. 2). Surprisingly, in nature we can count a number of examples where spinel occurs in peridotites in garnet-hosted primary diamond-bearing (hence UHP) multiphase inclusions from Bardane, Ugelvik and Svartberget in the Western Gneiss Region (van Roermund and Drury, 1998van Roermund, H.L.M., Drury, M.R. (1998) Ultra‐high pressure (P > 6 GPa) garnet peridotites in Western Norway: exhumation of mantle rocks from > 185 km depth. Terra Nova 10, 295–301.

; Van Roermund et al., 2002van Roermund, H.L.M., Carswell, D., Drury, M.R., Heijboer, T.C. (2002) Microdiamonds in a megacrystic garnet websterite pod from Bardane on the island of Fjørtoft, western Norway: evidence for diamond formation in mantle rocks during. Geology 30, 959–962.

; Carswell and van Roermund, 2005Carswell, D.A., van Roermund, H.L.M. (2005) On multi-phase mineral inclusions associated with microdiamond formation in mantle-derived peridotite lens at Bardane on Fjørtoft, west Norway. European Journal of Mineralogy 17, 31–42.

; Vrijmoed et al., 2006Vrijmoed, J.C., van Roermund, H.L.M., Davies, G.R. (2006) Evidence for diamond-grade ultra-high pressure metamorphism and fluid interaction in the Svartberget Fe–Ti garnet peridotite–websterite body, Western Gneiss Region, Norway. Mineralogy and Petrology 88, 381–405.

, 2008Vrijmoed, J., Smith, D., van Roermund, H.L.M. (2008) Raman confirmation of microdiamond in the Svartberget Fe‐Ti type garnet peridotite, Western Gneiss Region, Western Norway. Terra Nova 20, 295–301.

; van Roermund, 2009van Roermund, H.L.M. (2009) Mantle-wedge garnet peridotites from the northernmost ultra-high pressure domain of the Western Gneiss Region, SW Norway. European Journal of Mineralogy 21, 1085–1096.

; Malaspina et al., 2010Malaspina, N., Scambelluri, M., Poli, S., Van Roermund, H.L.M., Langenhorst, F. (2010) The oxidation state of mantle wedge majoritic garnet websterites metasomatised by C-bearing subduction fluids. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 417–426.

; Scambelluri et al., 2010Scambelluri, M., Van Roermund, H.L.M., Pettke, T. (2010) Mantle wedge peridotites: Fossil reservoirs of deep subduction zone processes. Lithos 120, 186–201.

). We will show that the growth of spinel, driven by a garnet dissolution-reprecipitation mechanism triggered by precise constraints on the composition of the supercritical liquid phase released by the slab, is possible also at UHP conditions.

Figure 1 (a) Photomicrograph of a multiphase solid inclusion in metasomatic garnet from Maowu Ultramafic Complex (Dabie Shan, China). Inset represents the relative orientation of the spinel {100} surface lattice (light blue) with respect to the garnet {100} surface lattice (violet) for the coincidence at θ = −45° (from Malaspina et al., 2015

Malaspina, N., Alvaro, M., Campione, M., Wilhelm, H., Nestola, F. (2015) Dynamics of mineral crystallization from precipitated slab-derived fluid phase: first in situ synchrotron X-ray measurements. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology 169, 26.

). (b) and (c) Negative-crystal shaped multiphase solid inclusion (plane polarised transmitted light and Secondary Electron image) with evident microstructural relations between spinel, chlorite and amphibole (gedrite).

Figure 2 Isochemical P-T section in the MASH system showing the predicted mineral assemblages calculated with Perple_X software package (Connolly, 1990

Connolly, A.D. (1990) Algorithm based on generalized thermodynamics. American Journal of Science 290, 666–718.

) for a bulk composition corresponding to pyrope [MgO (3 mol) - SiO2 (3 mol) - Al2O3 (1 mol)] + excess H2O. Mineral abbreviations: chl = chlorite, mctd = Mg-clorithoid, ta = talc, mcar = Mg-carpholite, ky = kyanite, q = quartz, opx = orthopyroxene, sud = sudoite, cor = corundum, sill = sillimanite, crd = cordierite, sapp = sapphirine.top

Results

Multiphase solid inclusions in garnet represent the heritage of a series of processes comprising: i) formation of the cavity, and ii) crystallisation of the solute within the cavity. The determined morphological and compositional features of the solid phases can be exploited in order to gain insights into the dynamics of these processes. Among the identified solid phases within microcavities in garnet, spinel occupies a distinctive position (Fig. 1). The reasons for that derive from the following characteristics, which were already evidenced by Malaspina et al. (2015)

Malaspina, N., Alvaro, M., Campione, M., Wilhelm, H., Nestola, F. (2015) Dynamics of mineral crystallization from precipitated slab-derived fluid phase: first in situ synchrotron X-ray measurements. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology 169, 26.

: i) spinel is not present in all the cavities, ii) spinel is the only (anhydrous) oxide phase when present, iii) spinel is the only epitaxial phase with garnet when present. On the basis of these characteristics, spinel was attributed a role as nucleation initiator for the solid phases occupying the cavity. Here, we obtain deeper insights into the crystallisation mechanism by the analysis of solution-solid equilibrium in a model MgO-Al2O3-SiO2-H2O (MASH) system and the application of principles of mass conservation.If aqueous fluids released by the slab equilibrate with solid phases, their molal composition would be close to 0.11, 0.18, and 3.7, in terms of dissolved MgO, Al2O3, and SiO2 components, in accordance with the experimental composition of the fluid phase in equilibrium with a K-free eclogite at 4 GPa and 800 °C (Kessel et al., 2005

Kessel, R., Ulmer, P., Pettke, T., Schmidt, M.W., Thompson, A.B. (2005) The water-basalt system at 4 to 6 GPa: Phase relations and second critical endpoint in a K-free eclogite at 700 to 1400 °C. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 237, 873–892.

; Fig. 3). This means that the water released by the dehydration of slab minerals might enrich by significant amounts the sole silica component, as far as its path is sufficiently long before the slab–mantle interface is reached. The effects of such fluids on the peridotite layer at the slab–mantle interface might be distinguished as follows: i) if slab-derived fluids are undersaturated with respect to peridotite minerals, the latter might undergo dissolution. Dissolution might be negligible if the fluid flow is fast and alternated by periods of dry conditions. On the contrary, dissolution might persist if the fluid is entrapped in cavities; ii) if in contact with a silica-rich fluid, the forsteritic component of the peridotite layer might react with the fluid, giving rise to an orthopyroxene-rich layer, according to the reaction Mg2SiO4 + SiO2 (aq) = Mg2Si2O6, acting as a "filter".At a late stage of process ii), the fluid escaping the orthopyroxene-rich filter might be at a composition in equilibrium with the mantle peridotite, namely 5.3, 0.31, and 3.0 in terms of MgO, Al2O3, and SiO2 molalities (Dvir et al., 2011

Dvir, O., Pettke, T., Fumagalli, P., Kessel, R. (2011) Fluids in the peridotite-water system up to 6 GPa and 800 °C: new experimental constraints on dehydration reactions. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology 161, 829–844.

, Fig. 3).

Figure 3 Chemography of the MgO-Al2O3-SiO2-H2O system at 4 GPa and 800 °C, projected from water, showing the stable assemblages coe-ky-py (purple field), py-en-fo (green), and py-sp-clin (yellow). Experimental equilibrium slab fluid compositions and mantle fluid compositions are indicated by purple and green dots, respectively. Calculated compositions of a fluid in equilibrium with py-sp-clin assemblage is indicated by a yellow dot. The bulk composition of the orthopyroxenite containing multiphase inclusions in garnet is indicated by a grey dot. Mineral abbreviations same as in Figure 2 and coe = coesite, mst = Mg-staurolite, py = pyrope, en = enstatite, clin = clinochlore, sp = spinel, fo = forsterite, chum = clinohumite, br = brucite.

As far as process i) is concerned, one should evaluate whether a subsequent event of dissolution-reprecipitation within pyrope cavities might bring about an equilibration of the fluid-solid system at the same P-T conditions of its formation. In order to demonstrate this evolution of the cavity, we must examine a hypothesis for the precipitating phases. On the basis of the assessed composition of our multiphase inclusions in pyrope-rich garnet (Malaspina et al., 2015

Malaspina, N., Alvaro, M., Campione, M., Wilhelm, H., Nestola, F. (2015) Dynamics of mineral crystallization from precipitated slab-derived fluid phase: first in situ synchrotron X-ray measurements. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology 169, 26.

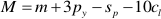

), it is clear that spinel and clinochlore can be reasonably considered the products of this precipitation, since the stable assemblage pyrope-spinel-clinochlore occurs only at P ≥ 4 GPa, and forsterite, corundum, Mg-staurolite, and coesite are never present within the cavity (Fig. S-1). Hence, the cavity should contain, at equilibrium, spinel and clinochlore as phases nucleated on pyrope after its dissolution, leaving a fluid with a composition in equilibrium with the pyrope-spinel-clinochlore assemblage.Pertinent chemical equations read:

Pyrope congruent dissolution:

If one refers to 1 kg H2O, the mass balance of the whole process reads:

where M, A, and S (m, a, and s) are the final (initial) molalities of MgO, Al2O3, and SiO2 of the fluid entrapped in the cavity, H are the moles of free water, py, sp, and cl are the moles of congruently dissolved pyrope, precipitated spinel, and precipitated clinochlore, respectively. The solution of this system of equations gives:

The constraint of positive values for py, sp, and cl allows us to define the space of the m, a, and s parameters, which determine the composition of the slab-derived fluid when the composition of the fluid in equilibrium with the pyrope-spinel-clinochlore assemblage is known. Such a fluid was calculated to have a composition of M = 0.15, A = 0.0096, and S = 0.12 (Supplementary Information, Fig. 3). These concentrations appear reliable if compared with the 0.13 molal experimental congruent solubility of garnet grossular (Fockenberg et al., 2008

Fockenberg, T., Burchard, M., Maresch, W. (2008) The solubility of natural grossular-rich garnet in pure water at high pressures and temperatures. European Journal of Mineralogy 20, 845–855.

). For our purposes, we consider the fluid in equilibrium with the pyrope-spinel-clinochlore assemblage to have concentrations within the intervals M = 0.15 ÷ 0.39, A = 0.0096 ÷ 0.13, and S = 0.12 ÷ 0.39, which give

A trivial upper limit of initial molalities is m = M, a = A, and s = S, which set to zero the first member of the equations, whereas the lowest limit of pure water (m = a = s = 0) is admitted. Since the m term is positive in each equation, the mass balance gives no constraint on the upper limit of m and, while cl increases with m, sp is independent of m. On the contrary, a silica-rich fluid as that in equilibrium with the slab (m = 0.11, a = 0.18, s = 3.7) would give rise to negative py, sp, and cl.

By way of an example, consider a fluid with composition m = 0.20, a = 0, and s = 0. Under this hypothesis the roots are py = 0.11 ÷ 0.23, sp = 0 ÷ 0.030, and cl = 0.035 ÷ 0.050 (H undergoes a decrement of 0.5÷0.7 %, which gives rise to a negligible correction of the previous molalities). By scaling these results on the volume of a typical cavity (104 µm3), considering that the molar volume of water is 14 cm3 mol-1 at 4 GPa and 800 °C (Zhang and Duan, 2005

Zhang, Z., Duan, Z. (2005) Prediction of the PVT properties of water over wide range of temperatures and pressures from molecular dynamics simulation. Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interiors 149, 335–354.

), the moles of pyrope dissolved in the cavity and the moles of precipitated spinel and clinochlore are (1.4 ÷ 2.9) × 10-12, (0 ÷ 3.8) × 10-13, and (4.5 ÷ 6.4) × 10-13, respectively. Assuming a molar volume of 110, 40 and 1100 cm3 mol-1 for pyrope, spinel, and clinochlore, respectively, the dissolved volume of pyrope is 150 ÷ 300 µm3, whereas the volume of precipitated spinel is 0 ÷ 15 µm3 and that of clinochlore is 500 ÷ 700 µm3. All these volume predictions are consistent with what is observed in nature (Fig. 1).top

Conclusions

The systematic presence of spinel + chlorite inclusions in many subduction zone mantle peridotites reflects a slab-mantle interface characterised by the transit of dilute aqueous fluids. These fluids are non-equilibrated fluids released by the slab minerals having the ability to dissolve garnet (Fig. 4). If slab-derived fluids are SiO2-enriched (Fig. 3), they will react with the overlying mantle peridotites forming orthopyroxenite layers (grey zone in Fig. 4). Once entrapped in the metasomatic-forming garnet (stage 1 in Fig. 4), they can dissolve it and bring the system to an equilibrium state of py-sp-clin assemblage (Fig. S-1) through a dissolution-reprecipitation mechanism (stage 2 in Fig. 4). The subsequent retrograde path undergone by the inclusion-bearing rock triggers the crystallisation of the other hydrous phases (gedrite, phlogopite, pargasite, talc), leaving an eventual residue of water solution (stage 3 in Fig. 4). In light of the drawn conclusions, spinel-chlorite bearing multiphase inclusions can be considered as witnesses of crystallisation processes at UHP. The fingerprint of such processes is sometimes revealed by a “surprising” composition which, if analysed solely by equilibrium arguments, would lead to incorrect inferences about their formation history.

Figure 4 Schematic cartoon showing aqueous fluid entrapped by growing metasomatic garnet (1) after the interaction of slab-derived supercritical liquid (SCL) and the supra-subduction mantle peridotite forming garnet orthopyroxenite (grey layer and veins). Light blue hexagons represent primary aqueous inclusions in pyrope. Garnet/fluid interaction yields a dissolution and precipitation process that triggers epitaxial nucleation of spinel and chlorite during garnet growing at UHP (2). Subsequent post-entrapment crystallisation of the other hydrous phases such as gedrite, phlogopite, pargasite and talc during the retrograde P-T path (3) leaves an eventual residue of water solution (light blue rim). Modified after Malaspina et al. (2017)

Malaspina, N., Langenhorst, F., Tumiati, S., Campione, M., Frezzotti, M.L., Poli, S. (2017) The redox budget of crust-derived fluid phases at the slab-mantle interface. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 209, 70–84.

.top

Acknowledgements

M. and S. T. thank the Italian Ministry of Education, University and Research (MIUR) [PRIN-2012R33ECR]. S. T. thanks the Deep Carbon Observatory (DCO) for financial support. All the authors acknowledge Dimitri Sverjensky for his valuable critical review comments.

Editor: Wendy Mao

top

References

Bureau, H., Keppler, H. (1999) Complete miscibility between silicate melts and hydrous fluids in the upper mantle: experimental evidence and geochemical implications. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 165, 187–196.

Show in context

Show in context Natural and experimental studies demonstrated that saline aqueous inclusions with variable solute load prevail in high pressure (HP) rocks (Scambelluri and Philippot, 2001; Touret, 2001), whereas multiphase solid inclusions in some ultrahigh pressure (UHP) rocks have been attributed to silicate-rich fluids or hydrous melts at supercritical conditions, namely supercritical liquids (Bureau and Keppler, 1999; Stöckhert et al., 2001; Carswell and van Roermund, 2005; Ferrando et al., 2005; Korsakov and Hermann, 2006; Malaspina et al., 2006).

View in article

Carswell, D.A., van Roermund, H.L.M. (2005) On multi-phase mineral inclusions associated with microdiamond formation in mantle-derived peridotite lens at Bardane on Fjørtoft, west Norway. European Journal of Mineralogy 17, 31–42.

Show in context

Show in context Natural and experimental studies demonstrated that saline aqueous inclusions with variable solute load prevail in high pressure (HP) rocks (Scambelluri and Philippot, 2001; Touret, 2001), whereas multiphase solid inclusions in some ultrahigh pressure (UHP) rocks have been attributed to silicate-rich fluids or hydrous melts at supercritical conditions, namely supercritical liquids (Bureau and Keppler, 1999; Stöckhert et al., 2001; Carswell and van Roermund, 2005; Ferrando et al., 2005; Korsakov and Hermann, 2006; Malaspina et al., 2006).

View in article

Surprisingly, in nature we can count a number of examples where spinel occurs in peridotites in garnet-hosted primary diamond-bearing (hence UHP) multiphase inclusions from Bardane, Ugelvik and Svartberget in the Western Gneiss Region (van Roermund and Drury, 1998; Van Roermund et al., 2002; Carswell and van Roermund, 2005; Vrijmoed et al., 2006, 2008; van Roermund, 2009; Malaspina et al., 2010; Scambelluri et al., 2010).

View in article

Chen, Y., Su, B., Chu, Z. (2017) Modification of an ancient subcontinental lithospheric mantle by continental subduction: Insight from the Maowu garnet peridotites in the Dabie UHP belt, eastern China. Lithos 278–281, 54–71.

Show in context

Show in context We will consider as a case study a well-known example of multiphase solid inclusions occurring in the cores of garnets forming orthopyroxenites from the Maowu Ultramafic Complex (Eastern China), interpreted as hybrid rocks resulting from the interaction of previous harzburgites and slab-derived silica-rich liquids (P = 4 GPa, T = 800 °C) at the slab-mantle interface (Malaspina et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2017).

View in article

Connolly, A.D. (1990) Algorithm based on generalized thermodynamics. American Journal of Science 290, 666–718.

Show in context

Show in context Figure 2 Isochemical P-T section in the MASH system showing the predicted mineral assemblages calculated with Perple_X software package (Connolly, 1990) for a bulk composition corresponding to pyrope [MgO (3 mol) - SiO2 (3 mol) - Al2O3 (1 mol)] + excess H2O.

View in article

Dvir, O., Pettke, T., Fumagalli, P., Kessel, R. (2011) Fluids in the peridotite-water system up to 6 GPa and 800 °C: new experimental constraints on dehydration reactions. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology 161, 829–844.

Show in context

Show in context At a late stage of process ii), the fluid escaping the orthopyroxene-rich filter might be at a composition in equilibrium with the mantle peridotite, namely 5.3, 0.31, and 3.0 in terms of MgO, Al2O3, and SiO2 molalities (Dvir et al., 2011, Fig. 3).

View in article

Ferrando, S., Frezzotti, M.L., Dallai, L., Compagnoni, R. (2005) Multiphase solid inclusions in UHP rocks (Su-Lu, China): Remnants of supercritical silicate-rich aqueous fluids released during continental subduction. Chemical Geology 223, 68–81.

Show in context

Show in context Natural and experimental studies demonstrated that saline aqueous inclusions with variable solute load prevail in high pressure (HP) rocks (Scambelluri and Philippot, 2001; Touret, 2001), whereas multiphase solid inclusions in some ultrahigh pressure (UHP) rocks have been attributed to silicate-rich fluids or hydrous melts at supercritical conditions, namely supercritical liquids (Bureau and Keppler, 1999; Stöckhert et al., 2001; Carswell and van Roermund, 2005; Ferrando et al., 2005; Korsakov and Hermann, 2006; Malaspina et al., 2006).

View in article

Fockenberg, T., Burchard, M., Maresch, W. (2008) The solubility of natural grossular-rich garnet in pure water at high pressures and temperatures. European Journal of Mineralogy 20, 845–855.

Show in context

Show in context These concentrations appear reliable if compared with the 0.13 molal experimental congruent solubility of garnet grossular (Fockenberg et al., 2008).

View in article

Frezzotti, M.L., Ferrando, S. (2015) The chemical behavior of fluids released during deep subduction based on fluid inclusions. American Mineralogist 100, 352–377.

Show in context

Show in context These inclusions are frequently hosted by minerals stable at mantle depths, such as garnet, and show the same textural features as fluid inclusions (Frezzotti and Ferrando, 2015; Fig. 1).

View in article

Kessel, R., Ulmer, P., Pettke, T., Schmidt, M.W., Thompson, A.B. (2005) The water-basalt system at 4 to 6 GPa: Phase relations and second critical endpoint in a K-free eclogite at 700 to 1400 °C. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 237, 873–892.

Show in context

Show in context If aqueous fluids released by the slab equilibrate with solid phases, their molal composition would be close to 0.11, 0.18, and 3.7, in terms of dissolved MgO, Al2O3, and SiO2 components, in accordance with the experimental composition of the fluid phase in equilibrium with a K-free eclogite at 4 GPa and 800 °C (Kessel et al., 2005; Fig. 3).

View in article

Korsakov, A.V., Hermann, J. (2006) Silicate and carbonate melt inclusions associated with diamonds in deeply subducted carbonate rocks. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 241, 104–118.

Show in context

Show in context Natural and experimental studies demonstrated that saline aqueous inclusions with variable solute load prevail in high pressure (HP) rocks (Scambelluri and Philippot, 2001; Touret, 2001), whereas multiphase solid inclusions in some ultrahigh pressure (UHP) rocks have been attributed to silicate-rich fluids or hydrous melts at supercritical conditions, namely supercritical liquids (Bureau and Keppler, 1999; Stöckhert et al., 2001; Carswell and van Roermund, 2005; Ferrando et al., 2005; Korsakov and Hermann, 2006; Malaspina et al., 2006).

View in article

Malaspina, N., Hermann, J., Scambelluri, M., Compagnoni, R. (2006) Polyphase inclusions in garnet–orthopyroxenite (Dabie Shan, China) as monitors for metasomatism and fluid-related trace element transfer in subduction zone peridotite. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 249, 173–187.

Show in context

Show in context Natural and experimental studies demonstrated that saline aqueous inclusions with variable solute load prevail in high pressure (HP) rocks (Scambelluri and Philippot, 2001; Touret, 2001), whereas multiphase solid inclusions in some ultrahigh pressure (UHP) rocks have been attributed to silicate-rich fluids or hydrous melts at supercritical conditions, namely supercritical liquids (Bureau and Keppler, 1999; Stöckhert et al., 2001; Carswell and van Roermund, 2005; Ferrando et al., 2005; Korsakov and Hermann, 2006; Malaspina et al., 2006).

View in article

We will consider as a case study a well-known example of multiphase solid inclusions occurring in the cores of garnets forming orthopyroxenites from the Maowu Ultramafic Complex (Eastern China), interpreted as hybrid rocks resulting from the interaction of previous harzburgites and slab-derived silica-rich liquids (P = 4 GPa, T = 800 °C) at the slab-mantle interface (Malaspina et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2017).

View in article

These multiphase inclusions have negative crystal shapes and constant volume proportions of the mineral infillings consisting of spinel ± orthopyroxene, and hydrous phases gedrite/pargasite, chlorite, phlogopite, ±talc, ±apatite (Malaspina et al., 2006, 2015; Fig. 1).

View in article

Malaspina, N., Scambelluri, M., Poli, S., Van Roermund, H.L.M., Langenhorst, F. (2010) The oxidation state of mantle wedge majoritic garnet websterites metasomatised by C-bearing subduction fluids. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 417–426.

Show in context

Show in context Surprisingly, in nature we can count a number of examples where spinel occurs in peridotites in garnet-hosted primary diamond-bearing (hence UHP) multiphase inclusions from Bardane, Ugelvik and Svartberget in the Western Gneiss Region (van Roermund and Drury, 1998; Van Roermund et al., 2002; Carswell and van Roermund, 2005; Vrijmoed et al., 2006, 2008; van Roermund, 2009; Malaspina et al., 2010; Scambelluri et al., 2010).

View in article

Malaspina, N., Alvaro, M., Campione, M., Wilhelm, H., Nestola, F. (2015) Dynamics of mineral crystallization from precipitated slab-derived fluid phase: first in situ synchrotron X-ray measurements. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology 169, 26.

Show in context

Show in context These multiphase inclusions have negative crystal shapes and constant volume proportions of the mineral infillings consisting of spinel ± orthopyroxene, and hydrous phases gedrite/pargasite, chlorite, phlogopite, ±talc, ±apatite (Malaspina et al., 2006, 2015; Fig. 1).

View in article

Recently, Malaspina et al. (2015) demonstrated the epitaxial relationship between spinel and garnet (Fig. 1a), which suggested nucleation of spinel under near-to-equilibrium conditions.

View in article

Figure 1 [...] Inset represents the relative orientation of the spinel {100} surface lattice (light blue) with respect to the garnet {100} surface lattice (violet) for the coincidence at θ = −45° (from Malaspina et al., 2015).

View in article

The reasons for that derive from the following characteristics, which were already evidenced by Malaspina et al. (2015): i) spinel is not present in all the cavities, ii) spinel is the only (anhydrous) oxide phase when present, iii) spinel is the only epitaxial phase with garnet when present.

View in article

On the basis of the assessed composition of our multiphase inclusions in pyrope-rich garnet (Malaspina et al., 2015), it is clear that spinel and clinochlore can be reasonably considered the products of this precipitation, since the stable assemblage pyrope-spinel-clinochlore occurs only at P ≥ 4 GPa, and forsterite, corundum, Mg-staurolite, and coesite are never present within the cavity (Fig. S-1).

View in article

Malaspina, N., Langenhorst, F., Tumiati, S., Campione, M., Frezzotti, M.L., Poli, S. (2017) The redox budget of crust-derived fluid phases at the slab-mantle interface. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 209, 70–84.

Show in context

Show in contextSome inclusions still preserve liquid water at the interface between mineral infillings and the cavity wall (Malaspina et al., 2017).

View in article

The epitaxial growth of spinel with respect to garnet and the chlorite rim + water assemblage filling the space between the host garnet and the other inclusion minerals (Malaspina et al., 2017), suggest that spinel and chlorite formed at UHP together with the garnet cores.

View in article

Figure 4 [...] Modified after Malaspina et al. (2017).

View in article

Niida, K., Green, D.H. (1999) Stability and chemical composition of pargasitic amphibole in MORB pyrolite under upper mantle conditions. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology 135, 18–40.

Show in context

Show in context However, spinel should be stable at UHP conditions neither in hydrous peridotites (Niida and Green, 1999), nor in a chemical system characterised by pyrope + H2O, at any P-T range (Fig. 2).

View in article

Scambelluri, M., Philippot, P. (2001) Deep fluids in subduction zones. Lithos 55, 213–227.

Show in context

Show in contextNatural and experimental studies demonstrated that saline aqueous inclusions with variable solute load prevail in high pressure (HP) rocks (Scambelluri and Philippot, 2001; Touret, 2001), whereas multiphase solid inclusions in some ultrahigh pressure (UHP) rocks have been attributed to silicate-rich fluids or hydrous melts at supercritical conditions, namely supercritical liquids (Bureau and Keppler, 1999; Stöckhert et al., 2001; Carswell and van Roermund, 2005; Ferrando et al., 2005; Korsakov and Hermann, 2006; Malaspina et al., 2006).

View in article

Scambelluri, M., Van Roermund, H.L.M., Pettke, T. (2010) Mantle wedge peridotites: Fossil reservoirs of deep subduction zone processes. Lithos 120, 186–201.

Show in context

Show in context Surprisingly, in nature we can count a number of examples where spinel occurs in peridotites in garnet-hosted primary diamond-bearing (hence UHP) multiphase inclusions from Bardane, Ugelvik and Svartberget in the Western Gneiss Region (van Roermund and Drury, 1998; Van Roermund et al., 2002; Carswell and van Roermund, 2005; Vrijmoed et al., 2006, 2008; van Roermund, 2009; Malaspina et al., 2010; Scambelluri et al., 2010).

View in article

Stöckhert, B., Duyster, J., Trepmann, C., Massonne, H., Sto, B. (2001) Microdiamond daughter crystals precipitated from supercritical COH + silicate fluids included in garnet, Erzgebirge, Germany. Geology 29, 391–394.

Show in context

Show in context Natural and experimental studies demonstrated that saline aqueous inclusions with variable solute load prevail in high pressure (HP) rocks (Scambelluri and Philippot, 2001; Touret, 2001), whereas multiphase solid inclusions in some ultrahigh pressure (UHP) rocks have been attributed to silicate-rich fluids or hydrous melts at supercritical conditions, namely supercritical liquids (Bureau and Keppler, 1999; Stöckhert et al., 2001; Carswell and van Roermund, 2005; Ferrando et al., 2005; Korsakov and Hermann, 2006; Malaspina et al., 2006).

View in article

Touret, J.L. (2001) Fluids in metamorphic rocks. Lithos 55, 1–25.

Show in context

Show in context Natural and experimental studies demonstrated that saline aqueous inclusions with variable solute load prevail in high pressure (HP) rocks (Scambelluri and Philippot, 2001; Touret, 2001), whereas multiphase solid inclusions in some ultrahigh pressure (UHP) rocks have been attributed to silicate-rich fluids or hydrous melts at supercritical conditions, namely supercritical liquids (Bureau and Keppler, 1999; Stöckhert et al., 2001; Carswell and van Roermund, 2005; Ferrando et al., 2005; Korsakov and Hermann, 2006; Malaspina et al., 2006).

View in article

van Roermund, H.L.M. (2009) Mantle-wedge garnet peridotites from the northernmost ultra-high pressure domain of the Western Gneiss Region, SW Norway. European Journal of Mineralogy 21, 1085–1096.

Show in context

Show in context Surprisingly, in nature we can count a number of examples where spinel occurs in peridotites in garnet-hosted primary diamond-bearing (hence UHP) multiphase inclusions from Bardane, Ugelvik and Svartberget in the Western Gneiss Region (van Roermund and Drury, 1998; Van Roermund et al., 2002; Carswell and van Roermund, 2005; Vrijmoed et al., 2006, 2008; van Roermund, 2009; Malaspina et al., 2010; Scambelluri et al., 2010).

View in article

van Roermund, H.L.M., Drury, M.R. (1998) Ultra‐high pressure (P > 6 GPa) garnet peridotites in Western Norway: exhumation of mantle rocks from > 185 km depth. Terra Nova 10, 295–301.

Show in context

Show in context Surprisingly, in nature we can count a number of examples where spinel occurs in peridotites in garnet-hosted primary diamond-bearing (hence UHP) multiphase inclusions from Bardane, Ugelvik and Svartberget in the Western Gneiss Region (van Roermund and Drury, 1998; Van Roermund et al., 2002; Carswell and van Roermund, 2005; Vrijmoed et al., 2006, 2008; van Roermund, 2009; Malaspina et al., 2010; Scambelluri et al., 2010).

View in article

van Roermund, H.L.M., Carswell, D., Drury, M.R., Heijboer, T.C. (2002) Microdiamonds in a megacrystic garnet websterite pod from Bardane on the island of Fjørtoft, western Norway: evidence for diamond formation in mantle rocks during. Geology 30, 959–962.

Show in context

Show in context Surprisingly, in nature we can count a number of examples where spinel occurs in peridotites in garnet-hosted primary diamond-bearing (hence UHP) multiphase inclusions from Bardane, Ugelvik and Svartberget in the Western Gneiss Region (van Roermund and Drury, 1998; Van Roermund et al., 2002; Carswell and van Roermund, 2005; Vrijmoed et al., 2006, 2008; van Roermund, 2009; Malaspina et al., 2010; Scambelluri et al., 2010).

View in article

Vrijmoed, J.C., van Roermund, H.L.M., Davies, G.R. (2006) Evidence for diamond-grade ultra-high pressure metamorphism and fluid interaction in the Svartberget Fe–Ti garnet peridotite–websterite body, Western Gneiss Region, Norway. Mineralogy and Petrology 88, 381–405.

Show in context

Show in context Surprisingly, in nature we can count a number of examples where spinel occurs in peridotites in garnet-hosted primary diamond-bearing (hence UHP) multiphase inclusions from Bardane, Ugelvik and Svartberget in the Western Gneiss Region (van Roermund and Drury, 1998; Van Roermund et al., 2002; Carswell and van Roermund, 2005; Vrijmoed et al., 2006, 2008; van Roermund, 2009; Malaspina et al., 2010; Scambelluri et al., 2010).

View in article

Vrijmoed, J., Smith, D., van Roermund, H.L.M. (2008) Raman confirmation of microdiamond in the Svartberget Fe‐Ti type garnet peridotite, Western Gneiss Region, Western Norway. Terra Nova 20, 295–301.

Show in context

Show in context Surprisingly, in nature we can count a number of examples where spinel occurs in peridotites in garnet-hosted primary diamond-bearing (hence UHP) multiphase inclusions from Bardane, Ugelvik and Svartberget in the Western Gneiss Region (van Roermund and Drury, 1998; Van Roermund et al., 2002; Carswell and van Roermund, 2005; Vrijmoed et al., 2006, 2008; van Roermund, 2009; Malaspina et al., 2010; Scambelluri et al., 2010).

View in article

Zhang, Z., Duan, Z. (2005) Prediction of the PVT properties of water over wide range of temperatures and pressures from molecular dynamics simulation. Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interiors 149, 335–354.

Show in context

Show in context By scaling these results on the volume of a typical cavity (104 µm3), considering that the molar volume of water is 14 cm3 mol-1 at 4 GPa and 800 °C (Zhang and Duan, 2005), the moles of pyrope dissolved in the cavity and the moles of precipitated spinel and clinochlore are (1.4 ÷ 2.9) × 10-12, (0 ÷ 3.8) × 10-13, and (4.5 ÷ 6.4) × 10-13, respectively. Assuming a molar volume of 110, 40 and 1100 cm3 mol-1 for pyrope, spinel, and clinochlore, respectively, the dissolved volume of pyrope is 150 ÷ 300 µm3, whereas the volume of precipitated spinel is 0 ÷ 15 µm3 and that of clinochlore is 500 ÷ 700 µm3.

View in article

top

Supplementary Information

Thermodynamic Modelling

The P-T isochemical section of Figure 2 was calculated by Gibbs free energy gridded minimisation with the software Perple_X (Connolly, 2005), considering a fixed bulk composition corresponding to pure pyrope (Mg3Al2Si3O12) at H2O-saturated conditions. We used the thermodynamic database and equation of state for H2O of Holland and Powell (1998).

The compatibility diagrams of Figure 3 and Figure S-1 were calculated with the software Perple_X in the MASH system (MgO-Al2O3-SiO2-H2O), projected from water.

MgO, Al2O3 and SiO2 dissolved in water in equilibrium with py + coe + ky (purple in Fig. 3), en + fo + py (green in Fig. 3), and py + cl + sp (yellow in Fig. 3) were calculated using the aqueous speciation-solubility code EQ3 (Wolery, 1992) adapted to include equilibrium constants calculated with the Deep Earth Water (DEW) model (Facq et al., 2014; Sverjensky et al., 2014). The results of such calculations are reported in Table S-1 for comparison with experimental (EXP) solubilities (molalities) found in literature.

Table S-1 MgO, Al2O3 and SiO2 molalities of aqueous solutions in equilibrium with different assemblages, calculated using the aqueous speciation-solubility code EQ3 adapted to include equilibrium constants calculated with the Deep Earth Water (DEW) model.

| Equilibrium slab-fluid | |

| DEW-EQ3 (py-coe-ky assemblage) | EXP (Kessel et al., 2005) purple dot in Figure 3 |

| m = 0.017 | m = 0.11 |

| a = 0.0037 | a = 0.18 |

| s = 1.77 | s = 3.7 |

| Equilibrium mantle-fluid | |

| DEW-EQ3 (en-fo-py assemblage) | EXP (Dvir et al., 2011) green dot in Figure 3 |

| m = 0.25 | m = 5.29 |

| a = 0.0026 | a = 0.31 |

| s = 0.20 | s = 3.0 |

| Fluid in equilibrium with py-sp-clin assemblage | |

| DEW-EQ3 | EXP (Fockenberg et al., 2008) yellow dot in Figure 3 |

| m = 0.15 | m = 0.39 |

| a = 0.0096 | a = 0.13 |

| s = 0.12 | s = 0.39 |

Figure S-1 Compatibility diagrams of the water-saturated MgO-Al2O3-SiO2-H2O system at 800 °C and 1.5–4 GPa, projected from water, showing that the stable assemblage pyrope-spinel-clinochlore occurs only at UHP conditions. Mineral abbreviations same as Figures 2 and 3 of the manuscript.

Supplementary Information References

Dvir, O., Pettke, T., Fumagalli, P., Kessel, R. (2011) Fluids in the peridotite-water system up to 6 GPa and 800 °C: new experimental constraints on dehydration reactions. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology 161, 829–844.

Facq, S., Daniel, I., Montagnac, G., Cardon, H., Sverjensky, D.A. (2014) In situ Raman study and thermodynamic model of aqueous carbonate speciation in equilibrium with aragonite under subduction zone conditions. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 132, 375–390.

Fockenberg, T., Burchard, M., Maresch, W. (2008) The solubility of natural grossular-rich garnet in pure water at high pressures and temperatures. European Journal of Mineralogy 20, 845–855.

Holland, T.J.B., Powell, R. (1998) An internally consistent thermodynamic data set for phases of petrologic interest. Journal of Metamorphic Geology 16, 309–43.

Kessel, R., Ulmer, P., Pettke, T., Schmidt, M.W., Thompson, A.B. (2005) The water-basalt system at 4 to 6 GPa: Phase relations and second critical endpoint in a K-free eclogite at 700 to 1400 °C. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 237, 873–892.

Sverjensky, D.A., Harrison, B., Azzolini, D. (2014) Water in the deep Earth: The dielectric constant and the solubilities of quartz and corundum to 60 kb and 1200 °C. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 129, 125–145.

Wolery, T.J. (1992) EQ3/6, A Software Package for Geochemical Modeling of Aqueous Systems: Package Overview and Installation Guide (Version 7.0). Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, Livermore, California.

Figures and Tables

Figure 1 (a) Photomicrograph of a multiphase solid inclusion in metasomatic garnet from Maowu Ultramafic Complex (Dabie Shan, China). Inset represents the relative orientation of the spinel {100} surface lattice (light blue) with respect to the garnet {100} surface lattice (violet) for the coincidence at θ = −45° (from Malaspina et al., 2015

Malaspina, N., Alvaro, M., Campione, M., Wilhelm, H., Nestola, F. (2015) Dynamics of mineral crystallization from precipitated slab-derived fluid phase: first in situ synchrotron X-ray measurements. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology 169, 26.

). (b) and (c) Negative-crystal shaped multiphase solid inclusion (plane polarised transmitted light and Secondary Electron image) with evident microstructural relations between spinel, chlorite and amphibole (gedrite).

Figure 2 Isochemical P-T section in the MASH system showing the predicted mineral assemblages calculated with Perple_X software package (Connolly, 1990

Connolly, A.D. (1990) Algorithm based on generalized thermodynamics. American Journal of Science 290, 666–718.

) for a bulk composition corresponding to pyrope [MgO (3 mol) - SiO2 (3 mol) - Al2O3 (1 mol)] + excess H2O. Mineral abbreviations: chl = chlorite, mctd = Mg-clorithoid, ta = talc, mcar = Mg-carpholite, ky = kyanite, q = quartz, opx = orthopyroxene, sud = sudoite, cor = corundum, sill = sillimanite, crd = cordierite, sapp = sapphirine.

Figure 3 Chemography of the MgO-Al2O3-SiO2-H2O system at 4 GPa and 800 °C, projected from water, showing the stable assemblages coe-ky-py (purple field), py-en-fo (green), and py-sp-clin (yellow). Experimental equilibrium slab fluid compositions and mantle fluid compositions are indicated by purple and green dots, respectively. Calculated compositions of a fluid in equilibrium with py-sp-clin assemblage is indicated by a yellow dot. The bulk composition of the orthopyrexenite containing multiphase inclusions in garnet is indicated by a grey dot. Mineral abbreviations same as in Figure 2 and coe = coesite, mst = Mg-staurolite, py = pyrope, en = enstatite, clin = clinochlore, sp = spinel, fo = forsterite, chum = clinohumite, br = brucite.

Figure 4 Schematic cartoon showing aqueous fluid entrapped by growing metasomatic garnet (1) after the interaction of slab-derived supercritical liquid (SCL) and the supra-subduction mantle peridotite forming garnet orthopyroxenite (grey layer and veins). Light blue hexagons represent primary aqueous inclusions in pyrope. Garnet/fluid interaction yields a dissolution and precipitation process that triggers epitaxial nucleation of spinel and chlorite during garnet growing at UHP (2). Subsequent post-entrapment crystallisation of the other hydrous phases such as gedrite, phlogopite, pargasite and talc during the retrograde P-T path (3) leaves an eventual residue of water solution (light blue rim). Modified after Malaspina et al. (2017)

Malaspina, N., Langenhorst, F., Tumiati, S., Campione, M., Frezzotti, M.L., Poli, S. (2017) The redox budget of crust-derived fluid phases at the slab-mantle interface. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 209, 70–84.

.Back to article

Supplementary Figures and Tables

Table S-1 MgO, Al2O3 and SiO2 molalities of aqueous solutions in equilibrium with different assemblages, calculated using the aqueous speciation-solubility code EQ3 adapted to include equilibrium constants calculated with the Deep Earth Water (DEW) model.

| Equilibrium slab-fluid | |

| DEW-EQ3 (py-coe-ky assemblage) | EXP (Kessel et al., 2005) purple dot in Figure 3 |

| m = 0.017 | m = 0.11 |

| a = 0.0037 | a = 0.18 |

| s = 1.77 | s = 3.7 |

| Equilibrium mantle-fluid | |

| DEW-EQ3 (en-fo-py assemblage) | EXP (Dvir et al., 2011) green dot in Figure 3 |

| m = 0.25 | m = 5.29 |

| a = 0.0026 | a = 0.31 |

| s = 0.20 | s = 3.0 |

| Fluid in equilibrium with py-sp-clin assemblage | |

| DEW-EQ3 | EXP (Fockenberg et al., 2008) yellow dot in Figure 3 |

| m = 0.15 | m = 0.39 |

| a = 0.0096 | a = 0.13 |

| s = 0.12 | s = 0.39 |

Figure S-1 Compatibility diagrams of the water-saturated MgO-Al2O3-SiO2-H2O system at 800 °C and 1.5–4 GPa, projected from water, showing that the stable assemblage pyrope-spinel-clinochlore occurs only at UHP conditions. Mineral abbreviations same as Figures 2 and 3 of the manuscript.