Ultra-high pressure and ultra-reduced minerals in ophiolites may form by lightning strikes

Affiliations | Corresponding Author | Cite as | Funding informationKeywords: diamond in ophiolite, silicides, carbides, native metals, fulgurite, fullerenes, lightning strikes

- Share this article

Article views:11,456Cumulative count of HTML views and PDF downloads.

- Download Citation

- Rights & Permissions

top

Abstract

Figures and Tables

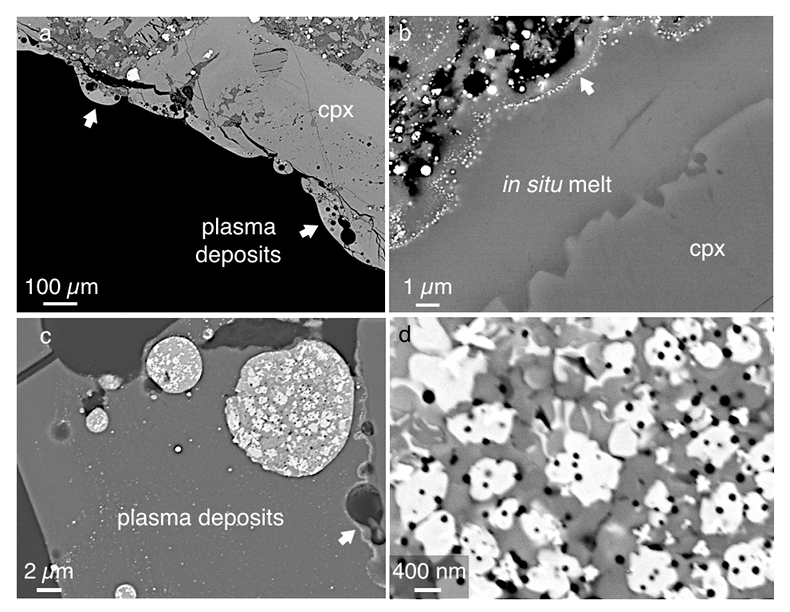

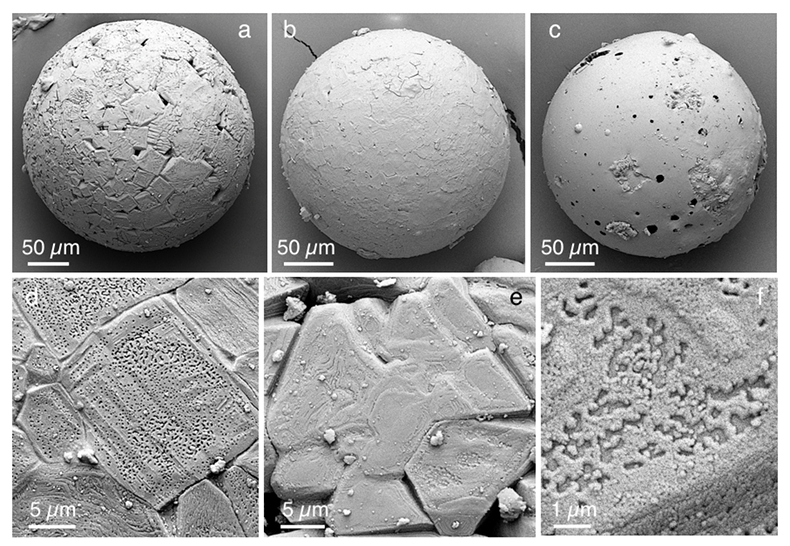

Figure 1 Experimental arrangement. A basalt cuboid surrounded by a 7 mm thick steel sleeve. The epoxy resin serves as electric insulator to prevent the current from short circuiting around the sample through the steel sleeve. Current pulses are generated with a pulse generator of the type SSG 10 kV/100 kJ (Haefely). The capacity of the pulse generator is 2140 µF. It can be charged to 10 kV. The energy achievable is 100 kJ. The pulse width depends on the load and is of the order of a few hundred microseconds. |  Figure 2 Images in BSE mode of plasma deposits. (a) Cross section of a crack covered by an up to 100 µm wide porous glass rim, resting upon a cpx phenocryst from the basaltic target rock. (b) Thermally resorbed cpx covered by inclusion-free glass (in situ melt), a chain of metal beads (arrow), and porous metal-bearing silicate glasses to the upper left (see text). (c) Larger exsolved metal globule within silicate glass; in situ glass to the right of the metal chain (arrow). (d) A metal globule in detail; bright quench phases are W-Ti metal, medium grey are Fe silicides, darker grey are SIC, and dark spherules are carbon condensates. |  Figure 3 Transmission electron (TEM) images of a metal globule. (a) Overview; bright Ti bearing W metals coexisting with Fe5Si3 xifengite, SiC moissanite (darker grey), and black carbon spherules (C). (b) Dark field image of W-Ti alloy in contact with xifengite. (c) HRTEM image of xifengite and fast Fourier transform (FFT) as inset. (d) Beta-SiC intergrown with Fe silicides. (e) HRTEM image of SiC with FFT as inset. (f) Amorphous carbon surrounded by graphene layers in concentric arrangement around amorphous cores, possibly shell fullerenes; FFTs as insets. |  Figure 4 Images of plasma spherules in secondary electron (SEM) mode, sputtered with Au. (a) and (b) Oxide spherules; surfaces composed of porous Fe-O oxide platelets. (c) Silicate glass spherule. (d) and (e) Surface crystals of Fe oxide spherules (? wüstite) in detail. (f) A quench oxide crystal on edge, apparently composed of multiple layers of nano-spherules. Note that all spherules shown are from an experiment where metallic Fe metal electrodes were used instead of W metal. |

| Figure 1 | Figure 2 | Figure 3 | Figure 4 |

top

Introduction

Until recently it was accepted that ophiolites form at low pressure along intra-oceanic spreading ridges (Lago et al., 1982

Lago, B.L., Rabinowicz, M., Nicolas, A. (1982) Podiform chromite ore bodies: a genetic model. Journal of Petrology 23, 103–125.

; Zhou et al., 1996Zhou, M.-F., Robinson, P.T., Malpas, J., Li, Z. (1996) Podiform chromitites in the Luobusa ophiolite (southern Tibet): Implications for melt-rock interaction and chromite segregation in the upper mantle. Journal of Petrology 37, 3–21.

; Matveev and Ballhaus, 2002Matveev, S., Ballhaus, C. (2002) Role of water in the origin of podiform chromitite deposits. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 203, 235–243.

). The identification of ultra-high pressure (UHP) phases in chromitites and harzburgites of ophiolite complexes (Robinson et al., 2004Robinson, P.T., Bai, W.J., Malpas, J., Yang, J.-S., Zhou, M.-F., Fang, Q.-S., Hu, X.-F., Cameron, S., Staudigel, H. (2004) Ultra-high pressure minerals in the Luobusa Ophiolite, Tibet, and their tectonic implications. Geological Society of London, Special Publications 226, 247–271.

; Yang et al., 2014Yang, J., Robinson, P.T., Dilek, Y. (2014) Diamonds in ophiolites: A little-known diamond occurrence. Elements 10, 127–130.

, 2015Yang, J., Meng, A., Xu, X., Robinson, P.T., Dilek, Y., Makeyev, A.B., Wirth, R., Wiedenbeck, M., Griffin, W.L., Cliff, J. (2015) Diamonds, native elements and metal alloys from chromitites of the Ray-Iz ophiolite of the Polar Urals. Gondwana Research 27, 459–485.

) appears to be changing that view. It is now being argued that mantle sections of ophiolites either originate in, or were processed within, the Earth’s mantle at depths as great as 600 km (Xiong et al., 2015Xiong, F., Yang, J., Robinson, P.T., Xu, X., Liu, Z., Yuan, L., Li, J., Songyong, C. (2015) Origin of podiform chromitite, a new model based on the Luobusa ophiolite, Tibet. Gondwana Research 27, 525–542.

; Xu et al., 2015Xu, X., Yang, J., Robinson, P.T., Xiong F., Ba, D., Guo, G. (2015) Origin of ultrahigh pressure and highly reduced minerals in podiform chromitites and associated mantle peridotites of the Luobusa ophiolite, Tibet. Gondwana Research 27, 686–700.

; Griffin et al., 2016Griffin, W.L., Afonso, J.C., Belousova, E.A., Gain, S.E., Gong, X.-H., González-Jiménez, J.M., Howell, D., Huang, J.-X., McGowan, N., Pearson, N.J., Satsukawa, T., Shi, R., Williams, P., Xiong, Q., Yang, J.-S., Zhang, M., O’Reilly, S.Y. (2016) Mantle recycling: Transition zone metamorphism of Tibetan ophiolitic peridotites and its tectonic implications. Journal of Petrology 57, 655–684.

). Furthermore, these UHP phases are often found associated with ultra-reduced minerals: native metals, silicides, carbides, and nitrides (Dobrzhinetskaya et al., 2009Dobrzhinetskaya, L.F., Wirth, R., Yang, J., Hutcheon, I.D., Weber, P.K., Green II, H.W. (2009) High-pressure highly reduced nitrides and oxides from chromitite of a Tibetan ophiolite. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 106, 19233–19238.

; Xu et al., 2015Xu, X., Yang, J., Robinson, P.T., Xiong F., Ba, D., Guo, G. (2015) Origin of ultrahigh pressure and highly reduced minerals in podiform chromitites and associated mantle peridotites of the Luobusa ophiolite, Tibet. Gondwana Research 27, 686–700.

). Consequently, it is speculated that the mantle source regions of ophiolites must be ultra-reduced.We question that the UHP and ultra-reduced phases are sufficient evidence to challenge long-established models of ophiolite genesis. Rather, alternative ways should be explored as to how these unusual mineral assemblages may have formed. We suggest that they may be the products of lightning strikes (Essene and Fisher, 1986

Essene, E.J., Fisher, D.C. (1986) Lightning strike fusion: Extreme reduction and metal-silicate liquid immiscibility. Science 234, 189–193.

; Daly et al., 1993Daly, T.K., Buseck, P.R., Williams, P., Lewis, C.F. (1993) Fullerenes from a fulgurite. Science 259, 1599–1601.

). Novel ultra-high temperature experiments at >6000 K reported here show that ultra-reduced phases can precipitate directly from plasmas. We do not identify diamond because our quench rates are too high, however, we do synthesise concentric shell fullerenes that may serve as nanoscopic pressure cells to vapour-deposited (CVD) diamonds (Banhart and Ayajan, 1996Banhart, F., Ajayan, P.M. (1996) Carbon onions as nanoscopic pressure cells for diamond formation. Nature 382, 433–435.

; Sorkin et al., 2011Sorkin, A., Tay, B., Su, H. (2011) Three-stage transformation pathway from nanodiamonds to fullerenes. The Journal of Physical Chemistry A 115, 8327–8334.

). The Luobusa ophiolite in Tibet where the unusual mineral assemblages are documented in most detail is situated at an altitude in excess of 4000 m, in a region where lightning strikes are frequent (Kumar and Kamra, 2012Kumar, R., Kamra, A.K. (2012) The spatiotemporal variability of lightning activity in the Himalayan foothills. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 117, doi: 10.1029/2012JD018246.

). The lithologies in which UHP and ultra-reduced minerals are found - serpentinised harzburgite and podiform chromitite - are electrically highly conductive lithologies and prone to attract lightning strikes.top

Experimental Strategy

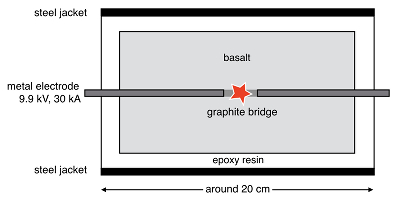

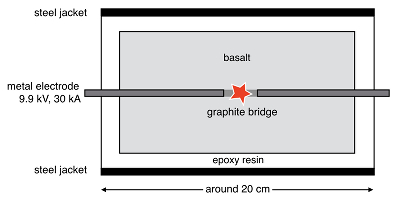

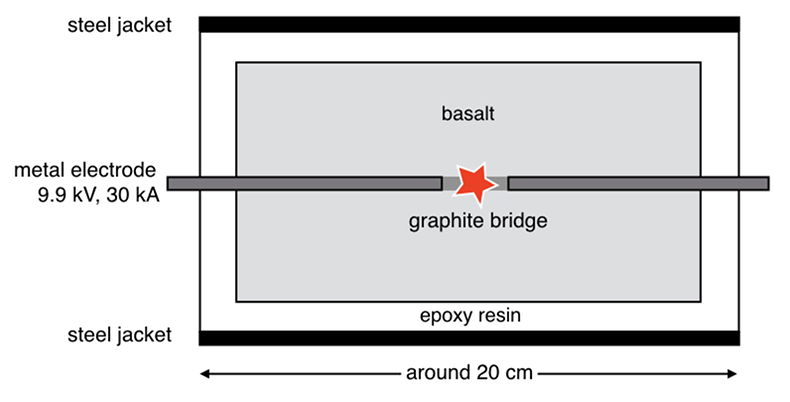

Basaltic samples are exposed to electric discharges that correspond in terms of current (30 kA) to natural cloud-to-ground lightning strikes (Uman, 1986

Uman, M.A. (1986) All About Lightning. Dover Publications Inc., New York.

). The samples are cut in cuboids, set in epoxy resin, and encased by steel sleeves. Tungsten metal electrodes are drilled into the front faces of the cuboids and bridged in the centre by a 10 mm long graphite rod (Fig. 1). The electrodes are then connected to a surge-current generator charged to 9.9 kV. The generator has a capacity of 2140 µF and produces a current surge of 30 kA for ~120 µs. Both the graphite rod and the tips of the W electrodes are vapourised upon electric discharge. A plasma is generated. The minimum temperature is given by the boiling point of metallic W (~6000 K). The samples shatter as a result of thermal expansion. Along the cracks, plasma jets escape and condense on the crack surfaces. The condensates carry ultra-reduced phases identical to those recovered from the Luobusa and Ray-Iz ophiolites.

Figure 1 Experimental arrangement. A basalt cuboid surrounded by a 7 mm thick steel sleeve. The epoxy resin serves as electric insulator to prevent the current from short circuiting around the sample through the steel sleeve. Current pulses are generated with a pulse generator of the type SSG 10 kV/100 kJ (Haefely). The capacity of the pulse generator is 2140 µF. It can be charged to 10 kV. The energy achievable is 100 kJ. The pulse width depends on the load and is of the order of a few hundred microseconds.

top

Results

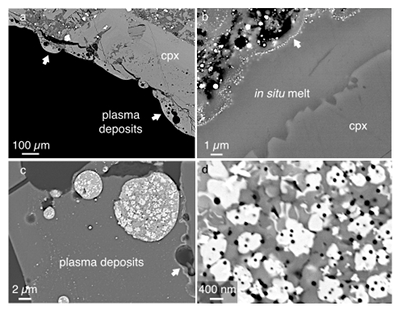

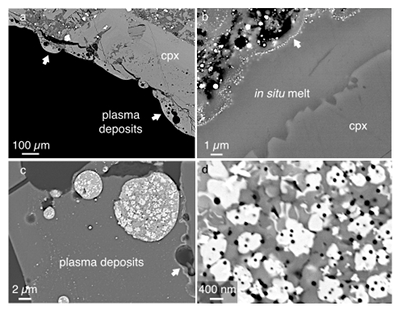

The plasma deposits tend to be up to 100 µm wide (Fig. 2a), consist of silicate glass with dispersed metal beads, and are distinctly zoned (Fig. 2b). On the thermally resorbed mineral surfaces (here a cpx phenocryst) we note an inclusion free in situ glass rim around 5 µm wide. Within analytical error, these in situ glasses have the same compositions as the minerals on which they rest. Then follows a chain of metal globules ~20 nm wide (arrow in Fig. 2b), separating the in situ glass layer from glass deposits rich in voids and metal blebs. The glasses above the metal chain are extremely heterogeneous on the micron scale: SiO2 from 15 to 67 wt. %, TiO2 from 0 to 6.6 wt. %, FeO from 0.6 to 62 wt. %, MgO from 0 to 52 wt. %, and CaO from 0.3 to 23 wt. %.

We scanned the larger metal blebs (Fig. 2c) in wavelength dispersive (WDS) mode for their major elements: W, Fe, and Si, as well as minor Ti and P. Tungsten is derived from the electrodes, Fe, Si, and P from the basaltic target rock, and Ti from titanomagnetite groundmass crystals of the basalt. Larger metal globules are polyphase (Fig. 2d), apparently because after liquefaction they exsolve. Two bright phases are identified as carriers of W and Ti, plus several medium grey phases enriched in Fe and Si with minor P. In addition, the metal globules are peppered by tiny dark spherules enriched in low atomic number elements, also found in the heterogeneous silicate glasses. Wavelength dispersive scans on the metal globules with the oxygen sensitive LDE-1 crystal show that the globules are oxide-free.

Figure 2 Images in BSE mode of plasma deposits. (a) Cross section of a crack covered by an up to 100 µm wide porous glass rim, resting upon a cpx phenocryst from the basaltic target rock. (b) Thermally resorbed cpx covered by inclusion-free glass (in situ melt), a chain of metal beads (arrow), and porous metal-bearing silicate glasses to the upper left (see text). (c) Larger exsolved metal globule within silicate glass; in situ glass to the right of the metal chain (arrow). (d) A metal globule in detail; bright quench phases are W-Ti metal, medium grey are Fe silicides, darker grey are SIC, and dark spherules are carbon condensates.

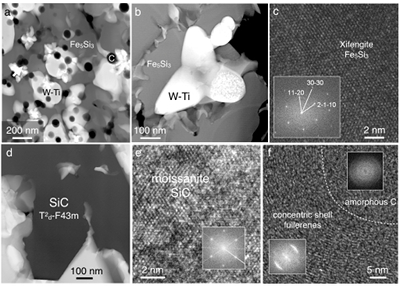

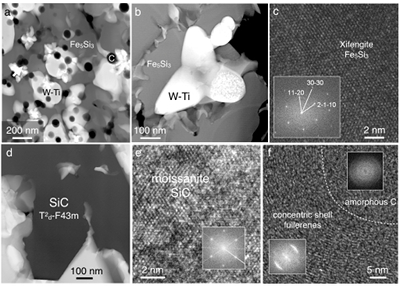

To identify the phases we investigated focussed ion beam (FIB) sections (Wirth, 2009

Wirth, R. (2009) Focused Ion Beam (FIB) combined with SEM and TEM: advanced analytical tools for studies of chemical composition, micro-structure and crystal structure in geomaterials on a nanometer scale. Chemical Geology 261, 217–229.

) from metal condensates with TEM (Fig. 3). The bright phases in Figure 3a and b are cubic Ti-bearing metallic W carrying still brighter dendritic quench phases that are enriched in Ti. Evidently, at ultra-high temperature Ti condenses as a metal species. Note that Ti-Fe-Si alloys and Ti carbides are reported from the Luobusa ophiolite and the Ray-Iz complex in the Polar Urals (Yang et al., 2007Yang, J., Dobrzhinetskaya, L.F., Bai, W.J., Junfeng Zhang, J., Green II, H.W. (2007) Diamond and coesite-bearing chromitites from the Luobusa ophiolite, Tibet. Geology 35, 875–878.

, 2014Yang, J., Robinson, P.T., Dilek, Y. (2014) Diamonds in ophiolites: A little-known diamond occurrence. Elements 10, 127–130.

, 2015Yang, J., Meng, A., Xu, X., Robinson, P.T., Dilek, Y., Makeyev, A.B., Wirth, R., Wiedenbeck, M., Griffin, W.L., Cliff, J. (2015) Diamonds, native elements and metal alloys from chromitites of the Ray-Iz ophiolite of the Polar Urals. Gondwana Research 27, 459–485.

). The medium grey phase (Fig. 3c) is hexagonal Fe5Si3 xifengite with minor P. Various Fe silicides including xifengite are reported from chromite-rich lithologies of Luobusa (Robinson et al., 2004Robinson, P.T., Bai, W.J., Malpas, J., Yang, J.-S., Zhou, M.-F., Fang, Q.-S., Hu, X.-F., Cameron, S., Staudigel, H. (2004) Ultra-high pressure minerals in the Luobusa Ophiolite, Tibet, and their tectonic implications. Geological Society of London, Special Publications 226, 247–271.

) and Ray-Iz (Yang et al., 2015Yang, J., Meng, A., Xu, X., Robinson, P.T., Dilek, Y., Makeyev, A.B., Wirth, R., Wiedenbeck, M., Griffin, W.L., Cliff, J. (2015) Diamonds, native elements and metal alloys from chromitites of the Ray-Iz ophiolite of the Polar Urals. Gondwana Research 27, 459–485.

). A minor phase is cubic SiC beta-moissanite (Fig. 3d,e), also known from Luobusa and Ray-Iz. In the experimental deposits, moissanite tends to form crystals sharply facetted against Fe-Si alloys. The dark rounded blebs are composed of carbon. The blebs imaged by TEM have amorphous cores surrounded by graphene units in concentric arrangement, known as onion shell fullerenes (Banhart and Ayajan, 1996Banhart, F., Ajayan, P.M. (1996) Carbon onions as nanoscopic pressure cells for diamond formation. Nature 382, 433–435.

). The spacing of the graphene layers (~0.357 ± 0.001 nm) is somewhat wider than the spacing of graphene layers in the graphite lattice (0.335 nm). Amorphous carbon is also reported from Luobusa (Yang et al., 2014Yang, J., Robinson, P.T., Dilek, Y. (2014) Diamonds in ophiolites: A little-known diamond occurrence. Elements 10, 127–130.

) and Ray-Iz (Yang et al., 2015Yang, J., Meng, A., Xu, X., Robinson, P.T., Dilek, Y., Makeyev, A.B., Wirth, R., Wiedenbeck, M., Griffin, W.L., Cliff, J. (2015) Diamonds, native elements and metal alloys from chromitites of the Ray-Iz ophiolite of the Polar Urals. Gondwana Research 27, 459–485.

), commonly around diamond but not documented structurally on the nano-scale.

Figure 3 Transmission electron (TEM) images of a metal globule. (a) Overview; bright Ti bearing W metals coexisting with Fe5Si3 xifengite, SiC moissanite (darker grey), and black carbon spherules (C). (b) Dark field image of W-Ti alloy in contact with xifengite. (c) HRTEM image of xifengite and fast Fourier transform (FFT) as inset. (d) Beta-SiC intergrown with Fe silicides. (e) HRTEM image of SiC with FFT as inset. (f) Amorphous carbon surrounded by graphene layers in concentric arrangement around amorphous cores, possibly shell fullerenes; FFTs as insets.

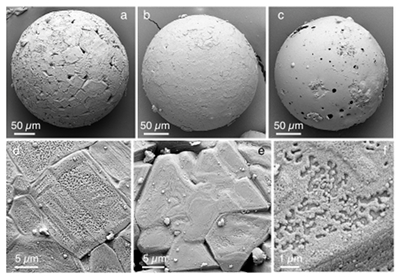

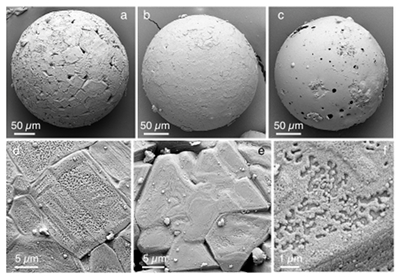

All electric discharges produce spherule ejecta (Fig. 4). We interpret these spherules as condensates of plasma jets that escape along cracks and are quenched in air. We document them here because similar spherules are reported, albeit not explained, from samples of Luobusa (Xu et al., 2015

Xu, X., Yang, J., Robinson, P.T., Xiong F., Ba, D., Guo, G. (2015) Origin of ultrahigh pressure and highly reduced minerals in podiform chromitites and associated mantle peridotites of the Luobusa ophiolite, Tibet. Gondwana Research 27, 686–700.

; Griffin et al., 2016Griffin, W.L., Afonso, J.C., Belousova, E.A., Gain, S.E., Gong, X.-H., González-Jiménez, J.M., Howell, D., Huang, J.-X., McGowan, N., Pearson, N.J., Satsukawa, T., Shi, R., Williams, P., Xiong, Q., Yang, J.-S., Zhang, M., O’Reilly, S.Y. (2016) Mantle recycling: Transition zone metamorphism of Tibetan ophiolitic peridotites and its tectonic implications. Journal of Petrology 57, 655–684.

). Many spherules are highly porous. Principal quench phases are non-stoichiometric Fe oxides, Fe metal phases, and silicate glass. The crystals on the surface of oxide spherules appear to be composed of packages of nanometre-sized droplets. The similarities to spherules from Luobusa and from fulgurites (Clocchiatti, 1990Clocchiatti, R. (1990) Les fulgurites et roches vitrifiées de l´Etna. European Journal of Mineralogy 2, 479–494.

) are striking.

Figure 4 Images of plasma spherules in secondary electron (SEM) mode, sputtered with Au. (a) and (b) Oxide spherules; surfaces composed of porous Fe-O oxide platelets. (c) Silicate glass spherule. (d) and (e) Surface crystals of Fe oxide spherules (? wüstite) in detail. (f) A quench oxide crystal on edge, apparently composed of multiple layers of nano-spherules. Note that all spherules shown are from an experiment where metallic Fe metal electrodes were used instead of W metal.

top

Discussion

It is obvious that the phases identified here are plasma precipitates. At temperatures where W metal is vapourised (ca. 6000 K) a gas consists to a large extent of positively charged species in an electron cloud which by definition is a plasma (Bittencourt, 2013

Bittencourt, J.A. (2013) Fundamentals of Plasma Physics. Third edition, Springer-Verlag, New York.

).The zonation pattern in Figure 2b illustrates how plasmas may evolve with cooling. Following the electric impulse, the plasma expands fracturing the sample. Some proportion of the plasma is ejected to air and condenses to oxide and silicate spherules (Fig. 4). Under natural conditions, such plasma jets could ignite and trigger ball lightning (Abrahamson and Dinniss, 2000

Abrahamson, J., Dinniss, J. (2000) Ball lightning caused by oxidation of nanoparticle networks from normal lightning strikes on soil. Nature 403, 519–521.

). While passing along the fractures, the plasma causes in situ flash melting. Note that the in situ glasses are inclusion-free on the TEM scale, notably free of W metal droplets. Apparently, when they form, the plasma is too hot to condense even its most refractory component (W metal), suggesting that temperatures could have exceeded the condensation point of W vapour (6000 K) by a comfortable margin. The first plasma condensates are refractory W-Fe-Si metal melt beads that form chains on top of the in situ glass rims. Most of the plasma is then liquefied and deposited in the form of multiple layers of a heterogeneous silicate melt (now glass), still with nano-sized metal and carbon spherules in suspension.Inside the metal beads we find highly reduced phases like Fe5Si3 and SiC. Apparently, the first condensation reactions are recombinations of positively charged gaseous species with electrons, according to

Eq. 1

5Fe+ + 3Si+ + 8e- (plasma) → Fe5Si3 (for xifengite),

Eq. 2

Si+ + C+ + 2e- (plasma) → SiC (for moissanite), and

Eq. 3

C+ + e- (plasma) → Carmophous → fullerenes (for the zoned carbon blebs)

In formulating these schematic reactions we assume (but do not insist) that the prevailing oxidation state of the cations in the plasma is 1+. The first condensates are highly refractory, ultra-reduced native metals and alloys, commonly Fe-Si alloys because FeO and SiO2 are major oxides in most lithologies and relatively easily ionised. Recombinations with oxygen do not seem to be important at least in the early stages of condensation (Jones et al., 2005

Jones, B.E., Jones, K.S., Rambo, K.J., Rakov, V.A., Jerald, J., Uman, M.A. (2005) Oxide reduction during triggered-lightning fulgurite formation. Journal of Atmospheric and Solar-Terrestrial Physics 67, 423–428.

) since oxides are less refractory than silicides and carbides. Our first and highest temperature condensates - W-Fe-Si metal beads - are oxygen free. At lower temperatures though, reaction with oxygen is commonplace. Most of the plasma is then deposited as heterogeneous silicate melt layers, likely as superheated liquids but now present as a metal-bearing, highly heterogeneous and porous glass.Our experiments produce phases identical to those found in “high pressure” ophiolites, including Fe-Si alloys, moissanite, metallic Ti within W-Ti alloys, amorphous carbon, and spherulitic ejecta. Some of the phases are highly reduced, however, because plasmas can condense on any type of substrate, their redox states (Golubkova et al., 2016

Golubkova, A., Schmidt, M.W., Connolly, J.A.D. (2016) Ultra-reducing conditions in average mantle peridotites and in podiform chromitites: a thermodynamic model for moissanite (SiC) formation. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology 171, doi: 10.1007/s00410-016-1253-9.

) are not diagnostic of the redox states of the rocks within which they occur. Our experiments also produce potential precursors to diamond. Concentric onion shell fullerenes, when they contract during cooling, can reach internal nano-scale pressures so high that they may nucleate diamond in their cores (Banhart and Ayajan, 1996Banhart, F., Ajayan, P.M. (1996) Carbon onions as nanoscopic pressure cells for diamond formation. Nature 382, 433–435.

). Other high pressure phases like coesite and stishovite may also form even though they are not found here: a dunite flash-heated to only 2100 K experiences a pressure pulse of 7 GPa (Liu and Li, 2006Liu, W., Li, B. (2006) Thermal equation of state of (Mg0.9Fe0.1)2SiO4 olivine. Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interiors 157, 188–195.

) if heating is isochoric. Our plasmas reach temperatures in excess of 6000 K and therefore potentially much higher pressures. That we do not find diamond or other high pressure phases may have experimental reasons: (1) the basalt cuboids disintegrate during discharge hence heating is not isochoric, and (2) the quench rates of our experimental plasmas are extremely short (milliseconds), much shorter than quench rates of natural fulgurites. Naturally generated lightning channels may be hotter, may be isochoric if they penetrate deep in solid rock, and may cool more slowly, leaving more time to nucleate high pressure phases.For the shell fullerenes produced here the carbon source is the graphite rod bridging the W electrodes. In natural diamonds and carbides of ophiolites the carbon source may be roots and soils. Indeed, diamonds and carbides from ophiolites have rather light and variable ∂13C (Trumbull et al., 2009

Trumbull, R.B., Yang, J.S., Robinson, P.T., Di Pierro, S., Vennemann, T., Wiedenbeck, M. (2009) The carbon isotope composition of natural SiC (moissanite) from the Earth's mantle: New discoveries from ophiolites. Lithos 113, 612–620.

; Yang et al., 2015Yang, J., Meng, A., Xu, X., Robinson, P.T., Dilek, Y., Makeyev, A.B., Wirth, R., Wiedenbeck, M., Griffin, W.L., Cliff, J. (2015) Diamonds, native elements and metal alloys from chromitites of the Ray-Iz ophiolite of the Polar Urals. Gondwana Research 27, 459–485.

) and highly positive ∂15N ratios (Howell et al., 2015Howell, D., Griffin, W.L., Yang, S., Gain, S., Stern, R.A.; Huang, J.-X., Jacob, D.E., Xu, X., Stokes, A.J., O'Reilly, S.Y., Pearson, N.J. (2015) Diamonds in ophiolites: Contamination or a new diamond growth environment? Earth and Planetary Science Letters 430, 284–295.

), matching in principle the respective isotope ratios of extant plant materials (Evans, 2001Evans, R.D. (2001) Physiological mechanisms influencing plant nitrogen isotope composition. Trends in Plant Science 6, 121–126.

; Bowling et al., 2008Bowling, D.R., Pataki, D.E., Randeron, J.T. (2008) Carbon isotopes in terrestrial ecosystem pools and CO2 fluxes. New Phytologist 178, 24–40.

). In the Luobusa diamonds, nitrogen is not aggregated (type 1B) unlike in diamonds with long residence times in the mantle (Cartigny et al., 2014Cartigny, P., Palot, M., Tomassot, E., Harris, J. (2014) Diamond formation: A stable isotope perspective. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 42, 699–732.

). Howell et al. (2015)Howell, D., Griffin, W.L., Yang, S., Gain, S., Stern, R.A.; Huang, J.-X., Jacob, D.E., Xu, X., Stokes, A.J., O'Reilly, S.Y., Pearson, N.J. (2015) Diamonds in ophiolites: Contamination or a new diamond growth environment? Earth and Planetary Science Letters 430, 284–295.

calculated an aggregation age of around 100 years. It would seem sensible then to analyse Luobusa diamonds and carbides for 14C. Should 14C be detected its presence would be the most convincing argument yet for a latter day origin of the UHP and highly reduced phases.top

Acknowledgements

We thank the workshops of the Steinmann Institut for sample preparation before and after experimentation and Georg Oleschinski for documenting the spherules. Discussions with Mei-Fu Zhou, John Malpas, and Feng-Pei Zhang, as well as insightful comments by Marian Tredoux and Rainer Abart helped clarify many arguments presented here. We also thank the editor Graham Pearson for handling the manuscript so efficiently. The first author would like to thank Paul Steinhardt for an extensive and enlightning email exchange some time ago on possible origins of ultra-reduced minerals in oxidised lithologies. The work was funded by the German Research Council with grant Ba 964/37 to C. Ballhaus.

Editor: Graham Pearson

top

References

Abrahamson, J., Dinniss, J. (2000) Ball lightning caused by oxidation of nanoparticle networks from normal lightning strikes on soil. Nature 403, 519–521.

Show in context

Show in context Under natural conditions, such plasma jets could ignite and trigger ball lightning (Abrahamson and Dinniss, 2000).

View in article

Banhart, F., Ajayan, P.M. (1996) Carbon onions as nanoscopic pressure cells for diamond formation. Nature 382, 433–435.

Show in context

Show in context We do not identify diamond because our quench rates are too high, however, we do synthesise concentric shell fullerenes that may serve as nanoscopic pressure cells to vapour-deposited (CVD) diamonds (Banhart and Ayajan, 1996; Sorkin et al., 2011).

View in article

The blebs imaged by TEM have amorphous cores surrounded by graphene units in concentric arrangement, known as onion shell fullerenes (Banhart and Ajayan, 1996).

View in article

Concentric onion shell fullerenes, when they contract during cooling, can reach internal nano-scale pressures so high that they may nucleate diamond in their cores (Banhart and Ayajan, 1996).

View in article

Bittencourt, J.A. (2013) Fundamentals of Plasma Physics. Third edition, Springer-Verlag, New York.

Show in context

Show in context At temperatures where W metal is vapourised (ca. 6000 K) a gas consists to a large extent of positively charged species in an electron cloud which by definition is a plasma (Bittencourt, 2013).

View in article

Bowling, D.R., Pataki, D.E., Randeron, J.T. (2008) Carbon isotopes in terrestrial ecosystem pools and CO2 fluxes. New Phytologist 178, 24–40.

Show in context

Show in context Indeed, diamonds and carbides from ophiolites have rather light and variable ∂13C (Trumbull et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2015) and highly positive ∂15N ratios (Howell et al., 2015), matching in principle the respective isotope ratios of extant plant materials (Evans, 2001; Bowling et al., 2008).

View in article

Cartigny, P., Palot, M., Tomassot, E., Harris, J. (2014) Diamond formation: A stable isotope perspective. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 42, 699–732.

Show in context

Show in context In the Luobusa diamonds, nitrogen is not aggregated (type 1B) unlike in diamonds with long residence times in the mantle (Cartigny et al., 2014).

View in article

Clocchiatti, R. (1990) Les fulgurites et roches vitrifiées de l´Etna. European Journal of Mineralogy 2, 479–494.

Show in context

Show in context The similarities to spherules from Luobusa and from fulgurites (Clocchiatti, 1990) are striking.

View in article

Daly, T.K., Buseck, P.R., Williams, P., Lewis, C.F. (1993) Fullerenes from a fulgurite. Science 259, 1599–1601.

Show in context

Show in context We suggest that they may be the products of lightning strikes (Essene and Fisher, 1986; Daly et al., 1993).

View in article

Dobrzhinetskaya, L.F., Wirth, R., Yang, J., Hutcheon, I.D., Weber, P.K., Green II, H.W. (2009) High-pressure highly reduced nitrides and oxides from chromitite of a Tibetan ophiolite. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 106, 19233–19238.

Show in context

Show in context Furthermore, these UHP phases are often found associated with ultra-reduced minerals: native metals, silicides, carbides, and nitrides (Dobrzhinetskaya et al., 2009; Xu et al., 2015).

View in article

Essene, E.J., Fisher, D.C. (1986) Lightning strike fusion: Extreme reduction and metal-silicate liquid immiscibility. Science 234, 189–193.

Show in context

Show in context We suggest that they may be the products of lightning strikes (Essene and Fisher, 1986; Daly et al., 1993).

View in article

Evans, R.D. (2001) Physiological mechanisms influencing plant nitrogen isotope composition. Trends in Plant Science 6, 121–126.

Show in context

Show in context Indeed, diamonds and carbides from ophiolites have rather light and variable ∂13C (Trumbull et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2015) and highly positive ∂15N ratios (Howell et al., 2015), matching in principle the respective isotope ratios of extant plant materials (Evans, 2001; Bowling et al., 2008).

View in article

Golubkova, A., Schmidt, M.W., Connolly, J.A.D. (2016) Ultra-reducing conditions in average mantle peridotites and in podiform chromitites: a thermodynamic model for moissanite (SiC) formation. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology 171, doi: 10.1007/s00410-016-1253-9.

Show in context

Show in context Some of the phases are highly reduced, however, because plasmas can condense on any type of substrate, their redox states (Golubkova et al., 2016) are not diagnostic of the redox states of the rocks within which they occur.

View in article

Griffin, W.L., Afonso, J.C., Belousova, E.A., Gain, S.E., Gong, X.-H., González-Jiménez, J.M., Howell, D., Huang, J.-X., McGowan, N., Pearson, N.J., Satsukawa, T., Shi, R., Williams, P., Xiong, Q., Yang, J.-S., Zhang, M., O’Reilly, S.Y. (2016) Mantle recycling: Transition zone metamorphism of Tibetan ophiolitic peridotites and its tectonic implications. Journal of Petrology 57, 655–684.

Show in context

Show in context It is now being argued that mantle sections of ophiolites either originate in, or were processed within, the Earth’s mantle at depths as great as 600 km (Xiong et al., 2015; Xu et al., 2015; Griffin et al., 2016).

View in article

We document them here because similar spherules are reported, albeit not explained, from samples of Luobusa (Xu et al., 2015; Griffin et al., 2016).

View in article

Howell, D., Griffin, W.L., Yang, S., Gain, S., Stern, R.A.; Huang, J.-X., Jacob, D.E., Xu, X., Stokes, A.J., O'Reilly, S.Y., Pearson, N.J. (2015) Diamonds in ophiolites: Contamination or a new diamond growth environment? Earth and Planetary Science Letters 430, 284–295.

Show in context

Show in context Indeed, diamonds and carbides from ophiolites have rather light and variable ∂13C (Trumbull et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2015) and highly positive ∂15N ratios (Howell et al., 2015), matching in principle the respective isotope ratios of extant plant materials (Evans, 2001; Bowling et al., 2008).

View in article

Howell et al. (2015) calculated an aggregation age of around 100 years.

View in article

Jones, B.E., Jones, K.S., Rambo, K.J., Rakov, V.A., Jerald, J., Uman, M.A. (2005) Oxide reduction during triggered-lightning fulgurite formation. Journal of Atmospheric and Solar-Terrestrial Physics 67, 423–428.

Show in context

Show in context Recombinations with oxygen do not seem to be important at least in the early stages of condensation (Jones et al., 2005) since oxides are less refractory than silicides and carbides.

View in article

Kumar, R., Kamra, A.K. (2012) The spatiotemporal variability of lightning activity in the Himalayan foothills. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 117, doi: 10.1029/2012JD018246.

Show in context

Show in context The Luobusa ophiolite in Tibet where the unusual mineral assemblages are documented in most detail is situated at an altitude in excess of 4000 m, in a region where lightning strikes are frequent (Kumar and Kamra, 2012).

View in article

Lago, B.L., Rabinowicz, M., Nicolas, A. (1982) Podiform chromite ore bodies: a genetic model. Journal of Petrology 23, 103–125.

Show in context

Show in context Until recently it was accepted that ophiolites form at low pressure along intra-oceanic spreading ridges (Lago et al., 1982; Zhou et al., 1996; Matveev and Ballhaus, 2002).

View in article

Liu, W., Li, B. (2006) Thermal equation of state of (Mg0.9Fe0.1)2SiO4 olivine. Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interiors 157, 188–195.

Show in context

Show in context Other high pressure phases like coesite and stishovite may also form even though they are not found here: a dunite flash-heated to only 2100 K experiences a pressure pulse of 7 GPa (Liu and Li, 2006) if heating is isochoric.

View in article

Matveev, S., Ballhaus, C. (2002) Role of water in the origin of podiform chromitite deposits. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 203, 235–243.

Show in context

Show in context Until recently it was accepted that ophiolites form at low pressure along intra-oceanic spreading ridges (Lago et al., 1982; Zhou et al., 1996; Matveev and Ballhaus, 2002).

View in article

Robinson, P.T., Bai, W.J., Malpas, J., Yang, J.-S., Zhou, M.-F., Fang, Q.-S., Hu, X.-F., Cameron, S., Staudigel, H. (2004) Ultra-high pressure minerals in the Luobusa Ophiolite, Tibet, and their tectonic implications. Geological Society of London, Special Publications 226, 247–271.

Show in context

Show in context The identification of ultra-high pressure (UHP) phases in chromitites and harzburgites of ophiolite complexes (Robinson et al., 2004; Yang et al., 2014, 2015) appears to be changing that view.

View in article

Various Fe silicides including xifengite are reported from chromite-rich lithologies of Luobusa (Robinson et al., 2004) and Ray-Iz (Yang et al., 2015).

View in article

Sorkin, A., Tay, B., Su, H. (2011) Three-stage transformation pathway from nanodiamonds to fullerenes. The Journal of Physical Chemistry A 115, 8327–8334.

Show in context

Show in context We do not identify diamond because our quench rates are too high, however, we do synthesise concentric shell fullerenes that may serve as nanoscopic pressure cells to vapour-deposited (CVD) diamonds (Banhart and Ayajan, 1996; Sorkin et al., 2011).

View in article

Trumbull, R.B., Yang, J.S., Robinson, P.T., Di Pierro, S., Vennemann, T., Wiedenbeck, M. (2009) The carbon isotope composition of natural SiC (moissanite) from the Earth's mantle: New discoveries from ophiolites. Lithos 113, 612–620.

Show in context

Show in context Indeed, diamonds and carbides from ophiolites have rather light and variable ∂13C (Trumbull et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2015) and highly positive ∂15N ratios (Howell et al., 2015), matching in principle the respective isotope ratios of extant plant materials (Evans, 2001; Bowling et al., 2008).

View in article

Uman, M.A. (1986) All About Lightning. Dover Publications Inc., New York.

Show in context

Show in context Basaltic samples are exposed to electric discharges that correspond in terms of current (30 kA) to natural cloud-to-ground lightning strikes (Uman, 1986).

View in article

Wirth, R. (2009) Focused Ion Beam (FIB) combined with SEM and TEM: advanced analytical tools for studies of chemical composition, micro-structure and crystal structure in geomaterials on a nanometer scale. Chemical Geology 261, 217–229.

Show in context

Show in context To identify the phases we investigated focussed ion beam (FIB) sections (Wirth, 2009) from metal condensates with TEM (Fig. 3).

View in article

Xiong, F., Yang, J., Robinson, P.T., Xu, X., Liu, Z., Yuan, L., Li, J., Songyong, C. (2015) Origin of podiform chromitite, a new model based on the Luobusa ophiolite, Tibet. Gondwana Research 27, 525–542.

Show in context

Show in context It is now being argued that mantle sections of ophiolites either originate in, or were processed within, the Earth’s mantle at depths as great as 600 km (Xiong et al., 2015; Xu et al., 2015; Griffin et al., 2016).

View in article

Xu, X., Yang, J., Robinson, P.T., Xiong F., Ba, D., Guo, G. (2015) Origin of ultrahigh pressure and highly reduced minerals in podiform chromitites and associated mantle peridotites of the Luobusa ophiolite, Tibet. Gondwana Research 27, 686–700.

Show in context

Show in context It is now being argued that mantle sections of ophiolites either originate in, or were processed within, the Earth’s mantle at depths as great as 600 km (Xiong et al., 2015; Xu et al., 2015; Griffin et al., 2016).

View in article

Furthermore, these UHP phases are often found associated with ultra-reduced minerals: native metals, silicides, carbides, and nitrides (Dobrzhinetskaya et al., 2009; Xu et al., 2015).

View in article

We document them here because similar spherules are reported, albeit not explained, from samples of Luobusa (Xu et al., 2015; Griffin et al., 2016).

View in article

Yang, J., Dobrzhinetskaya, L.F., Bai, W.J., Junfeng Zhang, J., Green II, H.W. (2007) Diamond and coesite-bearing chromitites from the Luobusa ophiolite, Tibet. Geology 35, 875–878.

Show in context

Show in context Note that Ti-Fe-Si alloys and Ti carbides are reported from the Luobusa ophiolite and the Ray-Iz complex in the Polar Urals (Yang et al., 2007, 2014, 2015).

View in article

Yang, J., Robinson, P.T., Dilek, Y. (2014) Diamonds in ophiolites: A little-known diamond occurrence. Elements 10, 127–130.

Show in context

Show in context The identification of ultra-high pressure (UHP) phases in chromitites and harzburgites of ophiolite complexes (Robinson et al., 2004; Yang et al., 2014, 2015) appears to be changing that view.

View in article

Note that Ti-Fe-Si alloys and Ti carbides are reported from the Luobusa ophiolite and the Ray-Iz complex in the Polar Urals (Yang et al., 2007, 2014, 2015).

View in article

Amorphous carbon is also reported from Luobusa (Yang et al., 2014) and Ray-Iz (Yang et al., 2015), commonly around diamond but not documented structurally on the nano-scale.

View in article

Yang, J., Meng, A., Xu, X., Robinson, P.T., Dilek, Y., Makeyev, A.B., Wirth, R., Wiedenbeck, M., Griffin, W.L., Cliff, J. (2015) Diamonds, native elements and metal alloys from chromitites of the Ray-Iz ophiolite of the Polar Urals. Gondwana Research 27, 459–485.

Show in context

Show in context The identification of ultra-high pressure (UHP) phases in chromitites and harzburgites of ophiolite complexes (Robinson et al., 2004; Yang et al., 2014, 2015) appears to be changing that view.

View in article

Note that Ti-Fe-Si alloys and Ti carbides are reported from the Luobusa ophiolite and the Ray-Iz complex in the Polar Urals (Yang et al., 2007, 2014, 2015).

View in article

Various Fe silicides including xifengite are reported from chromite-rich lithologies of Luobusa (Robinson et al., 2004) and Ray-Iz (Yang et al., 2015).

View in article

Amorphous carbon is also reported from Luobusa (Yang et al., 2014) and Ray-Iz (Yang et al., 2015), commonly around diamond but not documented structurally on the nano-scale.

View in article

Indeed, diamonds and carbides from ophiolites have rather light and variable ∂13C (Trumbull et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2015) and highly positive ∂15N ratios (Howell et al., 2015), matching in principle the respective isotope ratios of extant plant materials (Evans, 2001; Bowling et al., 2008).

View in article

Zhou, M.-F., Robinson, P.T., Malpas, J., Li, Z. (1996) Podiform chromitites in the Luobusa ophiolite (southern Tibet): Implications for melt-rock interaction and chromite segregation in the upper mantle. Journal of Petrology 37, 3–21.

Show in context

Show in context Until recently it was accepted that ophiolites form at low pressure along intra-oceanic spreading ridges (Lago et al., 1982; Zhou et al., 1996; Matveev and Ballhaus, 2002).

View in article

Figures and Tables

Figure 1 Experimental arrangement. A basalt cuboid surrounded by a 7 mm thick steel sleeve. The epoxy resin serves as electric insulator to prevent the current from short circuiting around the sample through the steel sleeve. Current pulses are generated with a pulse generator of the type SSG 10 kV/100 kJ (Haefely). The capacity of the pulse generator is 2140 µF. It can be charged to 10 kV. The energy achievable is 100 kJ. The pulse width depends on the load and is of the order of a few hundred microseconds.

Figure 2 Images in BSE mode of plasma deposits. (a) Cross section of a crack covered by an up to 100 µm wide porous glass rim, resting upon a cpx phenocryst from the basaltic target rock. (b) Thermally resorbed cpx covered by inclusion-free glass (in situ melt), a chain of metal beads (arrow), and porous metal-bearing silicate glasses to the upper left (see text). (c) Larger exsolved metal globule within silicate glass; in situ glass to the right of the metal chain (arrow). (d) A metal globule in detail; bright quench phases are W-Ti metal, medium grey are Fe silicides, darker grey are SIC, and dark spherules are carbon condensates.

Figure 3 Transmission electron (TEM) images of a metal globule. (a) Overview; bright Ti bearing W metals coexisting with Fe5Si3 xifengite, SiC moissanite (darker grey), and black carbon spherules (C). (b) Dark field image of W-Ti alloy in contact with xifengite. (c) HRTEM image of xifengite and fast Fourier transform (FFT) as inset. (d) Beta-SiC intergrown with Fe silicides. (e) HRTEM image of SiC with FFT as inset. (f) Amorphous carbon surrounded by graphene layers in concentric arrangement around amorphous cores, possibly shell fullerenes; FFTs as insets.

Figure 4 Images of plasma spherules in secondary electron (SEM) mode, sputtered with Au. (a) and (b) Oxide spherules; surfaces composed of porous Fe-O oxide platelets. (c) Silicate glass spherule. (d) and (e) Surface crystals of Fe oxide spherules (? wüstite) in detail. (f) A quench oxide crystal on edge, apparently composed of multiple layers of nano-spherules. Note that all spherules shown are from an experiment where metallic Fe metal electrodes were used instead of W metal.