Geochemistry and metallogeny of Neoproterozoic pyrite in oxic and anoxic sediments

Affiliations | Corresponding Author | Cite as | Funding information- Share this article

Article views:4,802Cumulative count of HTML views and PDF downloads.

- Download Citation

- Rights & Permissions

top

Abstract

Figures and Tables

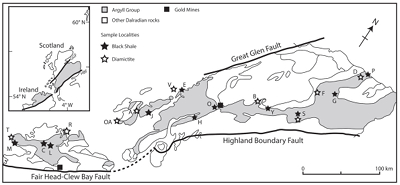

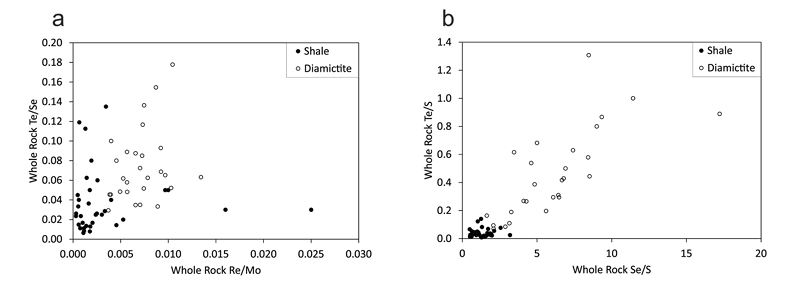

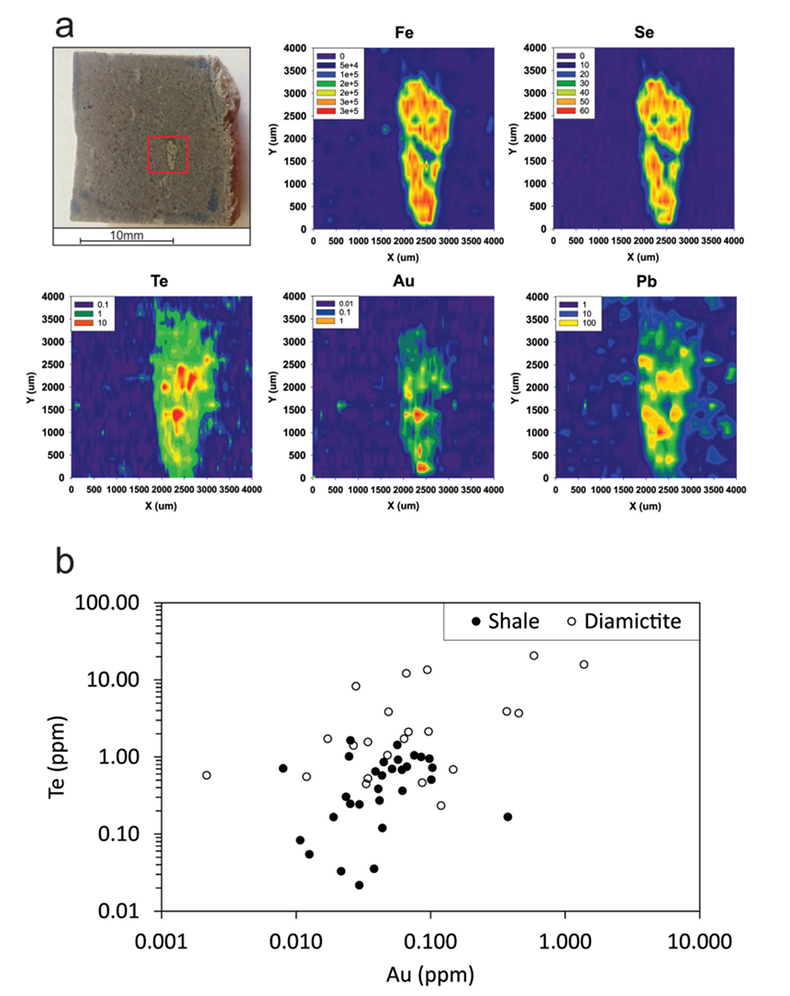

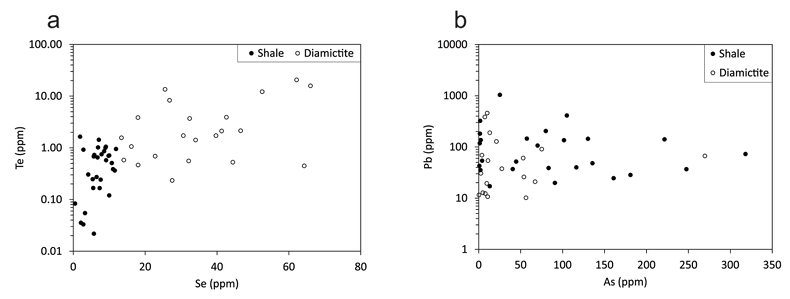

Figure 1 Sample map (after Prave et al., 2009). A, Port Askaig; B, Balmore; C, Cullion; D, Fordyce; E, Easdale; F, Meikle Fergie Burn; G, Glenbuchat; H, Strachur; J, Jura Forest; K, Kerrera; L, Bellanamore; M, Muckross; O, Strath Orchy; OA, Mull of Oa; P, Portsoy; R, Croaghan Hill; S, Glen Shee; T, Kiltyfannad/Glencolumbkille; V, Garvellachs; Y, Aberfeldy-Foss. |  Figure 2 Cross-plots of (a) Re/Mo ratio against Te/Se ratio for whole rock samples of diamictites and shales, showing a broad correlation. Both parameters increase with oxygenation of the environment. Samples below detection limit (0.001 ppm) for Re plotted at 50 % of limit. (b) Te/S against Se/S for whole rock samples of diamictites and shales. |  Figure 3 Gold in pyrite, determined by LA-ICP-MS. (a) Element maps for pyrite crystal in diamictite, Mull of Oa, Islay, Scotland. Counts in ppm, except Au counts per second. (b) Cross-plot of Au and Te contents in pyrite. 6 of 7 highest Au values recorded in diamictite. |  Figure 4 Cross-plots of (a) Te against Se contents, and (b) As and Pb contents in pyrite, measured by LA-ICP-MS. Highest concentrations of Te are in the diamictites. Arsenic contents are higher in the shales. Lead contents vary highly in both shales and diamictites, due to late addition by hydrothermal fluids. |

| Figure 1 | Figure 2 | Figure 3 | Figure 4 |

top

Introduction

The genesis of some ore deposits, including orogenic gold deposits, is believed to start with the sequestration of metals in diagenetic pyrite that grows in anoxic carbonaceous sediments (e.g., Pitcairn, 2011

Pitcairn, I.K. (2011) Background concentrations of gold in different rock types. Applied Earth Science 120, 31-38.

; Gaboury, 2013Gaboury, D. (2013) Does gold in orogenic deposits come from pyrite in deeply buried carbon-rich sediments?: Insight from volatiles in fluid inclusions. Geology 41, 1207-1210.

; Tomkins, 2013Tomkins, A.G. (2013) A biogeochemical influence on the secular distribution of orogenic gold. Economic Geology 108, 193-197.

). Pyrite is a product of microbial sulphate reduction at low temperature. Trace elements then become concentrated into vein minerals from this protolith during subsequent metamorphism and deformation. Widespread anoxic black shale deposition in the Neoproterozoic has been linked to a peak in orogenic gold deposits (Tomkins, 2013Tomkins, A.G. (2013) A biogeochemical influence on the secular distribution of orogenic gold. Economic Geology 108, 193-197.

). Diagenetic pyrite is most widely found in sediment deposited in reducing environments, such as the Neoproterozoic carbonaceous shales. However, the Neoproterozoic diamictites (tillites) deposited during the global glacial events known as ‘Snowball Earth’ also contain diagenetic pyrite (Parnell and Boyce, 2017Parnell, J., Boyce, A.J. (2017) Microbial sulphate reduction during Neoproterozoic glaciation, Port Askaig Formation, UK. Journal of the Geological Society, London 174, 850-854.

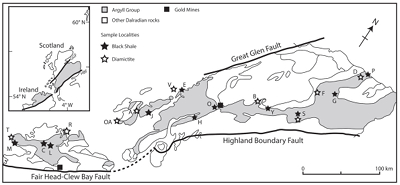

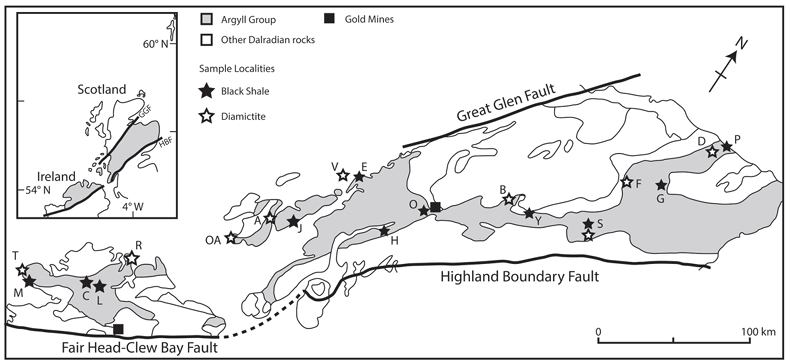

). The diamictites represent a more oxidising environment than the carbonaceous shales, and hence a different capacity to incorporate trace elements including economically important metals, which is Eh-controlled. The Neoproterozoic Argyll Group, Dalradian Supergroup (Fig. 1), includes both pyritic carbonaceous shales (Easdale Slate and correlatives) and diamictites (Port Askaig Formation) in Scotland and Ireland. Pyrite occurs disseminated through the shales, and in the diamictite is especially distributed at the surfaces of granite pebbles (Parnell and Boyce, 2017Parnell, J., Boyce, A.J. (2017) Microbial sulphate reduction during Neoproterozoic glaciation, Port Askaig Formation, UK. Journal of the Geological Society, London 174, 850-854.

). The Argyll Group thus offers the potential to compare trace element enrichment in both relatively reducing and oxidising environments. This can be measured using a combination of whole rock compositions and the detailed chemistry of diagenetic pyrite. The lithology can be excluded as a contributory factor, as both shale and diamictite have a homogenised provenance. Our results highlight the significance for metallogeny in the Dalradian Supergroup, which includes active gold mines (Fig. 1).The occurrence of five elements (Se, As, Te, Pb, Au) in pyrite is especially informative. Selenium is the most reliable indicator of seawater chemistry in pyrite samples (Large et al., 2014

Large, R.R., Hapin, J.A., Danyushevsky, L.V., Maslennikov, V.V., Bull, S.W., Long, J.A., Gregory, D.D., Lounejeva, E., Lyons, T.W., Sack, P.J., McGoldrick, P.J., Calver, C.R. (2014) Trace element content of sedimentary pyrite as a new proxy for deep-time ocean-atmosphere evolution. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 389, 209-220.

). Arsenic is commonly the most abundant trace element in pyrite, but varies with degree of oxidation of the depositional environment (Berner et al., 2013Berner, Z.A., Puchelt, H., Nöltner, T., Kramar, U. (2013) Pyrite geochemistry in the Toarcian Posidonia Shale of south-west Germany: Evidence for contrasting trace-element patterns of diagenetic and syngenetic pyrites. Sedimentology 60, 548-573.

). Tellurium was measured, as the Te/Se ratio is also proposed to be influenced by degree of oxidation (Schirmer et al., 2014Schirmer, T., Koschinsky, A., Bau, M. (2014) The ratio of tellurium and selenium in geological material as a possible paleo-redox proxy. Chemical Geology 376, 44-51.

). Lead tends to be introduced by hydrothermal activity (Tabelin et al., 2012Tabelin, C.B., Igarashi, T., Tamoto, S., Takahashi, R. (2012) The roles of pyrite and calcite in the mobilization of arsenic and lead from hydrothermally altered rocks excavated in Hokkaido, Japan. Journal of Geochemical Exploration 119, 17-31.

), and thus should be independent of the depositional environment. Gold was measured, as pyrite in carbonaceous shales is considered to be an important source of orogenic gold deposits (Tomkins, 2013Tomkins, A.G. (2013) A biogeochemical influence on the secular distribution of orogenic gold. Economic Geology 108, 193-197.

).

Figure 1 Sample map (after Prave et al., 2009

Prave, A.R., Fallick, A.E., Thomas, C.W., Graham, C.M. (2009) A composite C-isotope profile for the Neoproterozoic Dalradian Supergroup of Scotland. Journal of the Geological Society, London 166, 845-857.

). A, Port Askaig; B, Balmore; C, Cullion; D, Fordyce; E, Easdale; F, Meikle Fergie Burn; G, Glenbuchat; H, Strachur; J, Jura Forest; K, Kerrera; L, Bellanamore; M, Muckross; O, Strath Orchy; OA, Mull of Oa; P, Portsoy; R, Croaghan Hill; S, Glen Shee; T, Kiltyfannad/Glencolumbkille; V, Garvellachs; Y, Aberfeldy-Foss.top

Methodology

Samples of 35 pyritic shales and 28 diamictites were collected from 21 localities across the entire outcrop length of 450 km in Scotland and Ireland (Fig. 1, Table S-1). This database allowed representative coverage and duplicate sampling. At most localities the sediments are weakly metamorphosed to greenschist facies.

Trace element contents were measured in whole rock samples using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS). Samples of ~30 g rock were milled and homogenised, and 0.25 g digested with perchloric, nitric, hydrofluoric and hydrochloric acids to near dryness. The residue was topped up with dilute hydrochloric acid, and analysed using a Varian 725 instrument. Samples with high concentrations were diluted with hydrochloric acid to make a solution of 12.5 mL, homogenised, then analysed by ICP-MS. The limits of detection/resolution are 0.05 and 10,000 ppm.

Trace element analysis of pyrite in 29 shales, and 22 diamictites was performed using a New Wave laser ablation system UP213nm (New Wave Research, Fremont, CA) coupled to a inductive coupled plasma mass spectrometer (ICP-MS) Agilent 7900. The laser beam had a round spot size of 100 µm moving in a straight line, 10 Hz repetition rate and 50 µm s-1 ablation speed with 1 J/cm2 energy. Before ablation, a warm-up of 15 s was applied with 15 s delay between each ablation. The following isotopes were monitored (dwell time): 57Fe (0.001 s), 65Cu (0.001 s) 75As (0.05 s), 78Se (0.1 s), 82Se (0.1 s), 107Ag (0.1 s), 125Te (0.1 s), 126Te (0.1 s), 197Au (0.1 s), 208Pb (0.05 s) and 209Bi (0.1 s). Setting parameters were optimised daily by using NIST Glass 612, to obtain the maximum sensitivity and to ensure low oxide formation. In order to remove possible interferences, a reaction cell was used with hydrogen gas. The MASS-1 Synthetic Polymetal Sulfide standard (USGS, Reston, VA) was used to provide semi-quantification by calculating the ratio of concentration (µg g-1)/counts per second, and multiplying this ratio by the sample counts. Counts for Se, As, Te, Au and Pb were based on >100 measurements per sample, and thereafter converted to concentrations (ppm).

top

Results

Mean whole rock values for many trace elements in shales (Ag, Bi, Co, Cu, Mo, Pb, Se, Te, Zn) are equal to or higher than global mean values for shales (Supplementary Information), whereas mean values for some trace elements in diamictites are lower than global mean values for shales. However, the mean values for Se, Te, Cu, Co and V are higher in the diamictites than in the shales, for example Se (diamictites 2.6 ± 1.1 ppm, shales 2.1 ± 1.5 ppm, global mean shales 1.3 ppm) and Te (diamictites 0.13 ± 0.05 ppm, shales 0.07 ± 0.07 ppm, global mean shales 0.05 ppm). Au was not measured in whole rock samples.

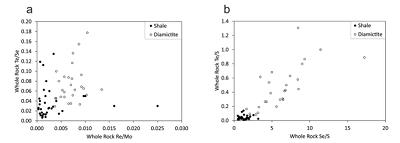

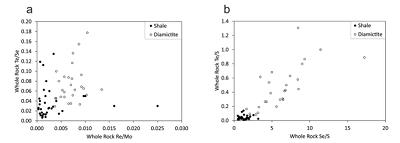

The relative concentrations of rhenium (Re) and molybdenum (Mo) in the whole rock samples allow assessment of the degree of oxygenation in the depositional environments (Crusius et al., 1996

Crusius, J., Calvert, S., Pedersen, T., Sage, D. (1996) Rhenium and molybdenum enrichments in sediments as indicators of oxic, suboxic and sulfidic conditions of deposition. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 145, 65-78.

). A Re/Mo ratio of about 0.005 wt./wt. separates samples deposited in suboxic concentrations (higher ratios) from those deposited in anoxic environments (lower ratios). The samples of diamictite have higher Re/Mo ratios (mean ratio value 0.007) than the samples of shale (0.001). Schirmer et al. (2014)Schirmer, T., Koschinsky, A., Bau, M. (2014) The ratio of tellurium and selenium in geological material as a possible paleo-redox proxy. Chemical Geology 376, 44-51.

proposed, from a limited data set, that the Te/Se ratio may also be influenced by degree of oxidation, hence may vary with depositional environment. The mean Te/Se ratios are 0.072 (diamictite) and 0.037 (shale), so both ratios have higher mean values in the diamictites (Fig. 2).Both Te and Se are largely resident in pyrite, as shown by the LA-ICP-MS data (below), so are best assessed normalised to sulphur contents, whereupon diamictites exhibit higher values of both Te/S (mean 0.45) and Se/S (6.12) than shales (Te/S 0.04, Se/S 1.30) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2 Cross-plots of (a) Re/Mo ratio against Te/Se ratio for whole rock samples of diamictites and shales, showing a broad correlation. Both parameters increase with oxygenation of the environment. Samples below detection limit (0.001 ppm) for Re plotted at 50 % of limit. (b) Te/S against Se/S for whole rock samples of diamictites and shales.

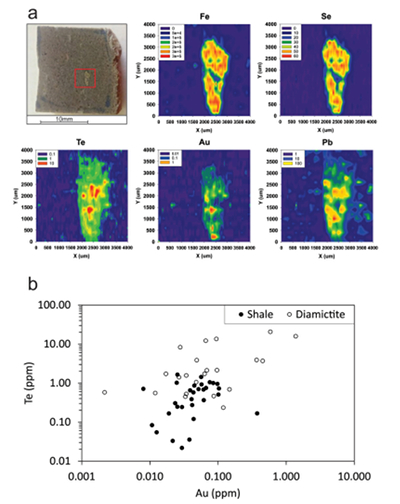

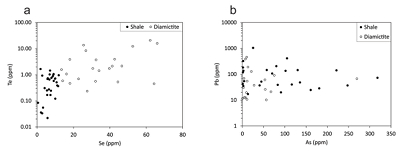

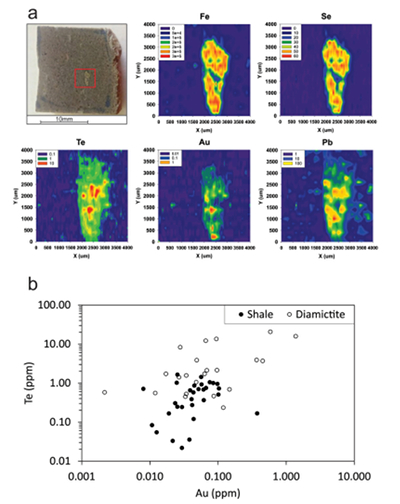

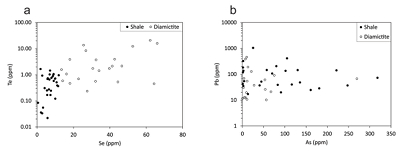

Element distribution maps prepared by LA-ICP-MS show that all of the trace elements measured are concentrated in pyrite, and occur at relatively negligible levels in the surrounding matrix (Fig. 3). Analyses of the pyrite show that Se contents are consistently higher in the diamictites (mean 35.1 ± 1 5.7 ppm) than in the shales (6.3 ± 3.1 ppm) (Fig. 4). There is overlap in the ranges of Te values for diamictites (4.4 ± 5.7 ppm) and shales (0.6 ± 0.5 ppm), but the highest Te values are all recorded in diamictites. The contents of As and Pb show a different distribution (Fig. 4). Arsenic levels are considerably higher in the shales (75.2 ± 79.3 ppm) than in the diamictites (35.2 ± 55.7 ppm), while a wide range of Pb contents are shown by both shales (139.5 ± 194.6 ppm) and diamictites (89.2 ± 123.4 ppm). Gold occurs in diamictite pyrite throughout (Fig. 3). Gold occurs in some shale-hosted pyrite, particularly in outer rims (Parnell et al., 2017

Parnell, J., Perez, M., Armstrong, J., Bullock, L., Feldmann, J., Boyce, A.J. (2017) A black shale protolith for gold-tellurium mineralization in the Dalradian Supergroup (Neoproterozoic) of Britain and Ireland. Applied Earth Science 126, 161-175, doi: 10.1080/03717453.2017.1404682.

), but less widely than in the diamictites. Semi-quantitative analyses of gold in diamictite pyrite yield higher values (mean 0.17 ± 0.30 ppm) than shale pyrite (mean 0.06 ± 0.06 ppm) (Fig. 3).

Figure 3 Gold in pyrite, determined by LA-ICP-MS. (a) Element maps for pyrite crystal in diamictite, Mull of Oa, Islay, Scotland. Counts in ppm, except Au counts per second. (b) Cross-plot of Au and Te contents in pyrite. 6 of 7 highest Au values recorded in diamictite.

Figure 4 Cross-plots of (a) Te against Se contents, and (b) As and Pb contents in pyrite, measured by LA-ICP-MS. Highest concentrations of Te are in the diamictites. Arsenic contents are higher in the shales. Lead contents vary highly in both shales and diamictites, due to late addition by hydrothermal fluids.

top

Discussion

Although pyrite typically forms in reducing environments, microbial sulphate reduction and sulphide precipitation can occur in microniches in otherwise oxidised sediment with Eh up to +300 mV (Jørgensen, 1977

Jørgensen, B.B. (1977) Bacterial sulfate reduction within reduced microniches of oxidized marine sediments. Marine Biology 41, 7-17.

). Such microniches are present particularly on particle surfaces, and have been recorded on granite pebbles (Lyew and Sheppard, 1997Lyew, D., Sheppard, J.D. (1997) Effects of physical parameters of a gravel bed on the activity of sulphate-reducing bacteria in the presence of acid mine drainage. Journal of Chemical Technology and Biotechnology 70, 223-230.

), which also focus pyrite formation in the diamictites during early diagenesis (Parnell and Boyce, 2017Parnell, J., Boyce, A.J. (2017) Microbial sulphate reduction during Neoproterozoic glaciation, Port Askaig Formation, UK. Journal of the Geological Society, London 174, 850-854.

). The texture of pyrite in both facies is clustered micro-crystals (Supplementary Information), so does not control variations in geochemistry.LA-ICP-MS evidence of trace element residence in pyrite shows that pyrite formation was fundamental to metal enrichment in both diamictites and shales. The LA-ICP-MS data show higher contents of Se, Te and Au in the diamictites. The whole rock and pyrite data bear out the supposition that trace element uptake would have differed in the shales and diamictites, due to contrasting degrees of oxygenation. The diamictites consistently have higher whole rock Re/Mo ratios that signify more oxidising conditions than the shales, which exhibit typical anoxic values (Crusius et al., 1996

Crusius, J., Calvert, S., Pedersen, T., Sage, D. (1996) Rhenium and molybdenum enrichments in sediments as indicators of oxic, suboxic and sulfidic conditions of deposition. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 145, 65-78.

). The Te/Se ratios are higher in the diamictites, also consistent with more oxidising conditions (Schirmer et al., 2014Schirmer, T., Koschinsky, A., Bau, M. (2014) The ratio of tellurium and selenium in geological material as a possible paleo-redox proxy. Chemical Geology 376, 44-51.

). A cross-plot of the two ratios shows that the parameters broadly correlate (Fig. 2). The greater degrees of enrichment in Cu, Co, and V in diamictites also points to oxidising conditions, as these elements are typically mobile at high Eh (Fischer and Stewart, 1961Fischer, R.P., Stewart, J.H. (1961) Copper, vanadium and uranium deposits in sandstone. Their distribution and geochemical cycles. Economic Geology 56, 509-520.

). Arsenic shows the opposite trend, of greater contents in the shales, consistent with higher uptake into pyrite in anoxic environments (Berner et al., 2013Berner, Z.A., Puchelt, H., Nöltner, T., Kramar, U. (2013) Pyrite geochemistry in the Toarcian Posidonia Shale of south-west Germany: Evidence for contrasting trace-element patterns of diagenetic and syngenetic pyrites. Sedimentology 60, 548-573.

). Lead is not preferentially concentrated in diamictites or shales, and is variably distributed, particularly in the margins of pyrite crystals (Parnell et al., 2017Parnell, J., Perez, M., Armstrong, J., Bullock, L., Feldmann, J., Boyce, A.J. (2017) A black shale protolith for gold-tellurium mineralization in the Dalradian Supergroup (Neoproterozoic) of Britain and Ireland. Applied Earth Science 126, 161-175, doi: 10.1080/03717453.2017.1404682.

), which suggests addition from late hydrothermal fluids.It is argued that the increase in atmospheric oxygenation following the Neoproterozoic glaciations was responsible for increased orogenic gold deposition (Tomkins, 2013

Tomkins, A.G. (2013) A biogeochemical influence on the secular distribution of orogenic gold. Economic Geology 108, 193-197.

). More oxygen would allow higher levels of dissolved gold in seawater (Vlassopoulos and Wood, 1990Vlassopoulos, D., Wood, S.A. (1990) Gold speciation in natural waters: Solubility and hydrolysis reactions of gold in aqueous solution. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 54, 3-12.

), which could in turn be incorporated into pyrite precipitated from marine pore waters. This gold is liable to be liberated during metamorphism and deformation, and becomes available to form orogenic gold deposits. Neoproterozoic oxygenation is similarly argued to explain higher selenium contents in mudrocks, selenium contents in pyrite, and a change in selenium isotope fractionation (Large et al., 2014Large, R.R., Hapin, J.A., Danyushevsky, L.V., Maslennikov, V.V., Bull, S.W., Long, J.A., Gregory, D.D., Lounejeva, E., Lyons, T.W., Sack, P.J., McGoldrick, P.J., Calver, C.R. (2014) Trace element content of sedimentary pyrite as a new proxy for deep-time ocean-atmosphere evolution. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 389, 209-220.

; Stüeken et al., 2015Stüeken, E.E., Buick, R., Bekker, A., Catling, D., Foriel, J., Guy, B.M., Kah, L.C., Machel, H.G., Montañez, I.P., Poulton, S.W. (2015) The evolution of the global selenium cycle: Secular trends in Se isotopes and abundances. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 162, 109-125.

). Tellurium also shows an increase in relative abundance from Precambrian to Phanerozoic due to oxygenation (Schirmer et al., 2014Schirmer, T., Koschinsky, A., Bau, M. (2014) The ratio of tellurium and selenium in geological material as a possible paleo-redox proxy. Chemical Geology 376, 44-51.

). If the additional oxygen in seawater allows greater uptake of gold and other trace elements in pyrite at/below the sea floor, pyrite in near-surface oxidising environments could have even higher potential to include gold. The evidence, from multiple parameters, of more oxidising conditions in the Dalradian diamictites than in the shales, and a consequent distinctive geochemistry in their pyrite, can explain their relatively high Au contents.The degree of oxygenation can also influence the uptake of gold in pyrite through the oxidation state of arsenic. Arsenic in pyrite enhances the uptake of a range of trace elements, especially gold (Deditius et al., 2008

Deditius, A.P., Utsunomiya, S., Renock, D., Ewing, R.C., Ramana, C.V., Becker, U., Kesler, S.E. (2008) A proposed new type of arsenian pyrite: Composition, nanostructure and geological significance. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 72, 2919-2933.

). In reducing environments, As (I) substitutes for S, while in oxidising conditions As (III) substitutes for Fe (II). Substitution by As (III) leaves vacancies that can accommodate large cations including Au+ (Deditius et al., 2008Deditius, A.P., Utsunomiya, S., Renock, D., Ewing, R.C., Ramana, C.V., Becker, U., Kesler, S.E. (2008) A proposed new type of arsenian pyrite: Composition, nanostructure and geological significance. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 72, 2919-2933.

). Thus pyrite found in more oxidising environments, as in the diamictites, could contain elevated contents of gold, relative to the contents in the shale.Trace elements in the pyrite are available for further concentration during metamorphism and deformation, including into cross-cutting vein systems (Large et al., 2011

Large, R.R., Bull, S.W., Maslennikov, V.V. (2011) A carbonaceous sedimentary source-rock model for Carlin-type and orogenic gold deposits. Economic Geology 106, 331-358.

). Thus, pyritic sediments may be a protolith for orogenic gold deposits (e.g., Pitcairn, 2011Pitcairn, I.K. (2011) Background concentrations of gold in different rock types. Applied Earth Science 120, 31-38.

; Tomkins, 2013Tomkins, A.G. (2013) A biogeochemical influence on the secular distribution of orogenic gold. Economic Geology 108, 193-197.

). Apart from evidence of Pb-rich fluid at the outermost rim of pyrite in some shale samples, the Dalradian pyrite chemistry is relatively uniform, showing that it has not been overprinted by metamorphism. The data reported here suggest that this model may be applicable to orogenic gold deposits in the Dalradian Supergroup, which are mined in both Scotland and Ireland (Fig. 1). However, the data imply that the diamictite-bearing section, which at the type locality of the Port Askaig Formation is 700 m thick, could contribute significantly to the protolith, which otherwise would be assumed to consist only of shales. The gold content in several diamictite pyrites (Fig. 3) exceeds the 0.25 ppm threshold suggested as indicative of gold ore potential (Large et al., 2011Large, R.R., Bull, S.W., Maslennikov, V.V. (2011) A carbonaceous sedimentary source-rock model for Carlin-type and orogenic gold deposits. Economic Geology 106, 331-358.

). The diamictites sampled occur over 450 km, representing a large volume of rock with elevated trace element contents. The pyrite in Dalradian diamictites exemplifies a global occurrence of pyrite in ‘Snowball Earth’ diamictites (Parnell and Boyce, 2017Parnell, J., Boyce, A.J. (2017) Microbial sulphate reduction during Neoproterozoic glaciation, Port Askaig Formation, UK. Journal of the Geological Society, London 174, 850-854.

), whose metallogenic potential deserves to be investigated.top

Conclusions

Data sets for trace elements in both whole rocks and pyrite show a contrast between diamictites and shales in the Argyll subgroup. In particular:

(i) Trace elements, including Se, Te, As, Pb and Au, were sequestered especially into pyrite.

(ii) Tellurium and Se, and also redox-sensitive elements Cu, Co, and V, uptake was higher into the diamictites than into the shales.

(iii) Gold enrichment also occurs in the pyrite, especially in diamictite-hosted pyrite.

(iv) Multiple parameters indicate a greater degree of oxygenation in the diamictites.

Combined, these observations suggest that greater oxygenation engendered greater uptake of trace elements, including Te, Se and Au into pyrite. The model of an anoxic shale protolith for orogenic gold deposits pertains because most pyrite forms in anoxic sediments. However, an awareness of the potential trace element reservoir in more oxygenated environments may lead to the discovery of hitherto unknown gold prospects.

top

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the NERC under Grant number NE/L001764/1. AJB is funded by NERC support of the Isotope Community Support Facility at SUERC. We are grateful to S. Mojzsis and I. Mukherjee for critical reviews, and A. Spencer and K. Mackay for help with sampling.

Editor: Eric H. Oelkers

top

References

Berner, Z.A., Puchelt, H., Nöltner, T., Kramar, U. (2013) Pyrite geochemistry in the Toarcian Posidonia Shale of south-west Germany: Evidence for contrasting trace-element patterns of diagenetic and syngenetic pyrites. Sedimentology 60, 548-573.

Show in context

Show in contextArsenic is commonly the most abundant trace element in pyrite, but varies with degree of oxidation of the depositional environment (Berner et al., 2013).

View in article

Arsenic shows the opposite trend, of greater contents in the shales, consistent with higher uptake into pyrite in anoxic environments (Berner et al., 2013).

View in article

Crusius, J., Calvert, S., Pedersen, T., Sage, D. (1996) Rhenium and molybdenum enrichments in sediments as indicators of oxic, suboxic and sulfidic conditions of deposition. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 145, 65-78.

Show in context

Show in contextThe relative concentrations of rhenium (Re) and molybdenum (Mo) in the whole rock samples allow assessment of the degree of oxygenation in the depositional environments (Crusius et al., 1996).

View in article

The diamictites consistently have higher whole rock Re/Mo ratios that signify more oxidising conditions than the shales, which exhibit typical anoxic values (Crusius et al., 1996).

View in article

Deditius, A.P., Utsunomiya, S., Renock, D., Ewing, R.C., Ramana, C.V., Becker, U., Kesler, S.E. (2008) A proposed new type of arsenian pyrite: Composition, nanostructure and geological significance. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 72, 2919-2933.

Show in context

Show in context Arsenic in pyrite enhances the uptake of a range of trace elements, especially gold (Deditius et al., 2008).

View in article

Substitution by As (III) leaves vacancies that can accommodate large cations including Au+ (Deditius et al., 2008).

View in article

Fischer, R.P., Stewart, J.H. (1961) Copper, vanadium and uranium deposits in sandstone. Their distribution and geochemical cycles. Economic Geology 56, 509-520.

Show in context

Show in context The greater degrees of enrichment in Cu, Co, and V in diamictites also points to oxidising conditions, as these elements are typically mobile at high Eh (Fischer and Stewart, 1961).

View in article

Gaboury, D. (2013) Does gold in orogenic deposits come from pyrite in deeply buried carbon-rich sediments?: Insight from volatiles in fluid inclusions. Geology 41, 1207-1210.

Show in context

Show in context The genesis of some ore deposits, including orogenic gold deposits, is believed to start with the sequestration of metals in diagenetic pyrite that grows in anoxic carbonaceous sediments (e.g., Pitcairn, 2011; Gaboury, 2013; Tomkins, 2013).

View in article

Jørgensen, B.B. (1977) Bacterial sulfate reduction within reduced microniches of oxidized marine sediments. Marine Biology 41, 7-17.

Show in context

Show in contextAlthough pyrite typically forms in reducing environments, microbial sulphate reduction and sulphide precipitation can occur in microniches in otherwise oxidised sediment with Eh up to +300 mV (Jørgensen, 1977).

View in article

Large, R.R., Bull, S.W., Maslennikov, V.V. (2011) A carbonaceous sedimentary source-rock model for Carlin-type and orogenic gold deposits. Economic Geology 106, 331-358.

Show in context

Show in contextTrace elements in the pyrite are available for further concentration during metamorphism and deformation, including into cross-cutting vein systems (Large et al., 2011).

View in article

The gold content in several diamictite pyrites (Fig. 3) exceeds the 0.25 ppm threshold suggested as indicative of gold ore potential (Large et al. 2011).

View in article

Large, R.R., Hapin, J.A., Danyushevsky, L.V., Maslennikov, V.V., Bull, S.W., Long, J.A., Gregory, D.D., Lounejeva, E., Lyons, T.W., Sack, P.J., McGoldrick, P.J., Calver, C.R. (2014) Trace element content of sedimentary pyrite as a new proxy for deep-time ocean-atmosphere evolution. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 389, 209-220.

Show in context

Show in contextSelenium is the most reliable indicator of seawater chemistry in pyrite samples (Large et al., 2014).

View in article

Neoproterozoic oxygenation is similarly argued to explain higher selenium contents in mudrocks, selenium contents in pyrite, and a change in selenium isotope fractionation (Large et al., 2014; Stüeken et al., 2015).

View in article

Lyew, D., Sheppard, J.D. (1997) Effects of physical parameters of a gravel bed on the activity of sulphate-reducing bacteria in the presence of acid mine drainage. Journal of Chemical Technology and Biotechnology 70, 223-230.

Show in context

Show in contextSuch microniches are present particularly on particle surfaces, and have been recorded on granite pebbles (Lyew and Sheppard, 1997), which also focus pyrite formation in the diamictites during early diagenesis (Parnell and Boyce, 2017).

View in article

Parnell, J., Boyce, A.J. (2017) Microbial sulphate reduction during Neoproterozoic glaciation, Port Askaig Formation, UK. Journal of the Geological Society, London 174, 850-854.

Show in context

Show in context However, the Neoproterozoic diamictites (tillites) deposited during the global glacial events known as ‘Snowball Earth’ also contain diagenetic pyrite (Parnell and Boyce, 2017).

View in article

Pyrite occurs disseminated through the shales, and in the diamictite is especially distributed at the surfaces of granite pebbles (Parnell and Boyce, 2017).

View in article

Such microniches are present particularly on particle surfaces, and have been recorded on granite pebbles (Lyew and Sheppard, 1997), which also focus pyrite formation in the diamictites during early diagenesis (Parnell and Boyce, 2017).

View in article

The pyrite in Dalradian diamictites exemplifies a global occurrence of pyrite in ‘Snowball Earth’ diamictites (Parnell and Boyce, 2017), whose metallogenic potential deserves to be investigated.

View in article

Parnell, J., Perez, M., Armstrong, J., Bullock, L., Feldmann, J., Boyce, A.J. (2017) A black shale protolith for gold-tellurium mineralization in the Dalradian Supergroup (Neoproterozoic) of Britain and Ireland. Applied Earth Science 126, 161-175, doi: 10.1080/03717453.2017.1404682.

Show in context

Show in context Gold occurs in some shale-hosted pyrite, particularly in outer rims (Parnell et al., 2017), but less widely than in the diamictites.

View in article

Lead is not preferentially concentrated in diamictites or shales, and is variably distributed, particularly in the margins of pyrite crystals (Parnell et al., 2017), which suggests addition from late hydrothermal fluids.

View in article

Pitcairn, I.K. (2011) Background concentrations of gold in different rock types. Applied Earth Science 120, 31-38.

Show in context

Show in contextThe genesis of some ore deposits, including orogenic gold deposits, is believed to start with the sequestration of metals in diagenetic pyrite that grows in anoxic carbonaceous sediments (e.g., Pitcairn, 2011; Gaboury, 2013; Tomkins, 2013).

View in article

Thus, pyritic sediments may be a protolith for orogenic gold deposits (e.g., Pitcairn, 2011; Tomkins, 2013).

View in article

Prave, A.R., Fallick, A.E., Thomas, C.W., Graham, C.M. (2009) A composite C-isotope profile for the Neoproterozoic Dalradian Supergroup of Scotland. Journal of the Geological Society, London 166, 845-857.

Show in context

Show in contextFigure 1 Sample map (after Prave et al., 2009).

View in article

Schirmer, T., Koschinsky, A., Bau, M. (2014) The ratio of tellurium and selenium in geological material as a possible paleo-redox proxy. Chemical Geology 376, 44-51.

Show in context

Show in context Tellurium was measured, as the Te/Se ratio is also proposed to be influenced by degree of oxidation (Schirmer et al., 2014).

View in article

Schirmer et al. (2014) proposed, from a limited data set, that the Te/Se ratio may also be influenced by degree of oxidation, hence may vary with depositional environment.

View in article

The Te/Se ratios are higher in the diamictites, also consistent with more oxidising conditions (Schirmer et al., 2014).

View in article

Tellurium also shows an increase in relative abundance from Precambrian to Phanerozoic due to oxygenation (Schirmer et al., 2014).

View in article

Stüeken, E.E., Buick, R., Bekker, A., Catling, D., Foriel, J., Guy, B.M., Kah, L.C., Machel, H.G., Montañez, I.P., Poulton, S.W. (2015) The evolution of the global selenium cycle: Secular trends in Se isotopes and abundances. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 162, 109-125.

Show in context

Show in context Neoproterozoic oxygenation is similarly argued to explain higher selenium contents in mudrocks, selenium contents in pyrite, and a change in selenium isotope fractionation (Large et al., 2014; Stüeken et al., 2015).

View in article

Tabelin, C.B., Igarashi, T., Tamoto, S., Takahashi, R. (2012) The roles of pyrite and calcite in the mobilization of arsenic and lead from hydrothermally altered rocks excavated in Hokkaido, Japan. Journal of Geochemical Exploration 119, 17-31.

Show in context

Show in contextLead tends to be introduced by hydrothermal activity (Tabelin et al., 2012), and thus should be independent of the depositional environment.

View in article

Tomkins, A.G. (2013) A biogeochemical influence on the secular distribution of orogenic gold. Economic Geology 108, 193-197.

Show in context

Show in context The genesis of some ore deposits, including orogenic gold deposits, is believed to start with the sequestration of metals in diagenetic pyrite that grows in anoxic carbonaceous sediments (e.g., Pitcairn, 2011; Gaboury, 2013; Tomkins, 2013).

View in article

Widespread anoxic black shale deposition in the Neoproterozoic has been linked to a peak in orogenic gold deposits (Tomkins, 2013).

View in article

Gold was measured, as pyrite in carbonaceous shales is considered to be an important source of orogenic gold deposits (Tomkins, 2013).

View in article

It is argued that the increase in atmospheric oxygenation following the Neoproterozoic glaciations was responsible for increased orogenic gold deposition (Tomkins, 2013).

View in article

Thus, pyritic sediments may be a protolith for orogenic gold deposits (e.g., Pitcairn, 2011; Tomkins, 2013).

View in article

Vlassopoulos, D., Wood, S.A. (1990) Gold speciation in natural waters: Solubility and hydrolysis reactions of gold in aqueous solution. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 54, 3-12.

Show in context

Show in context More oxygen would allow higher levels of dissolved gold in seawater (Vlassopoulos and Wood, 1990), which could in turn be incorporated into pyrite precipitated from marine pore waters.

View in article

top

Supplementary Information

The Supplementary Information includes:

- Tables S-1 and S-2

- Figures S-1 and S-2

- Supplementary Information References

Download the Supplementary Information (PDF).

Figures and Tables

Figure 1 Sample map (after Prave et al., 2009

Prave, A.R., Fallick, A.E., Thomas, C.W., Graham, C.M. (2009) A composite C-isotope profile for the Neoproterozoic Dalradian Supergroup of Scotland. Journal of the Geological Society, London 166, 845-857.

). A, Port Askaig; B, Balmore; C, Cullion; D, Fordyce; E, Easdale; F, Meikle Fergie Burn; G, Glenbuchat; H, Strachur; J, Jura Forest; K, Kerrera; L, Bellanamore; M, Muckross; O, Strath Orchy; OA, Mull of Oa; P, Portsoy; R, Croaghan Hill; S, Glen Shee; T, Kiltyfannad/Glencolumbkille; V, Garvellachs; Y, Aberfeldy-Foss.

Figure 2 Cross-plots of (a) Re/Mo ratio against Te/Se ratio for whole rock samples of diamictites and shales, showing a broad correlation. Both parameters increase with oxygenation of the environment. Samples below detection limit (0.001 ppm) for Re plotted at 50 % of limit. (b) Te/S against Se/S for whole rock samples of diamictites and shales.

Figure 3 Gold in pyrite, determined by LA-ICP-MS. (a) Element maps for pyrite crystal in diamictite, Mull of Oa, Islay, Scotland. Counts in ppm, except Au counts per second. (b) Cross-plot of Au and Te contents in pyrite. 6 of 7 highest Au values recorded in diamictite.

Figure 4 Cross-plots of (a) Te against Se contents, and (b) As and Pb contents in pyrite, measured by LA-ICP-MS. Highest concentrations of Te are in the diamictites. Arsenic contents are higher in the shales. Lead contents vary highly in both shales and diamictites, due to late addition by hydrothermal fluids.