Early differentiation of magmatic iron meteorite parent bodies from Mn–Cr chronometry

Affiliations | Corresponding Author | Cite as | Funding information- Share this article

Article views:205Cumulative count of HTML views and PDF downloads.

- Download Citation

- Rights & Permissions

top

Abstract

Figures and Tables

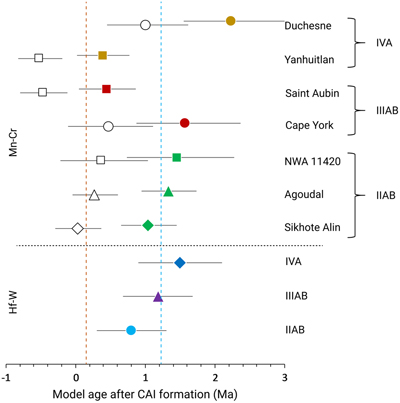

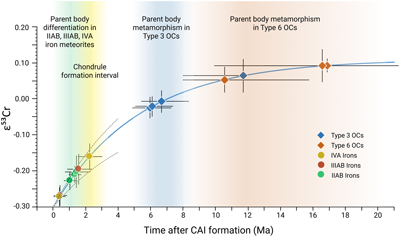

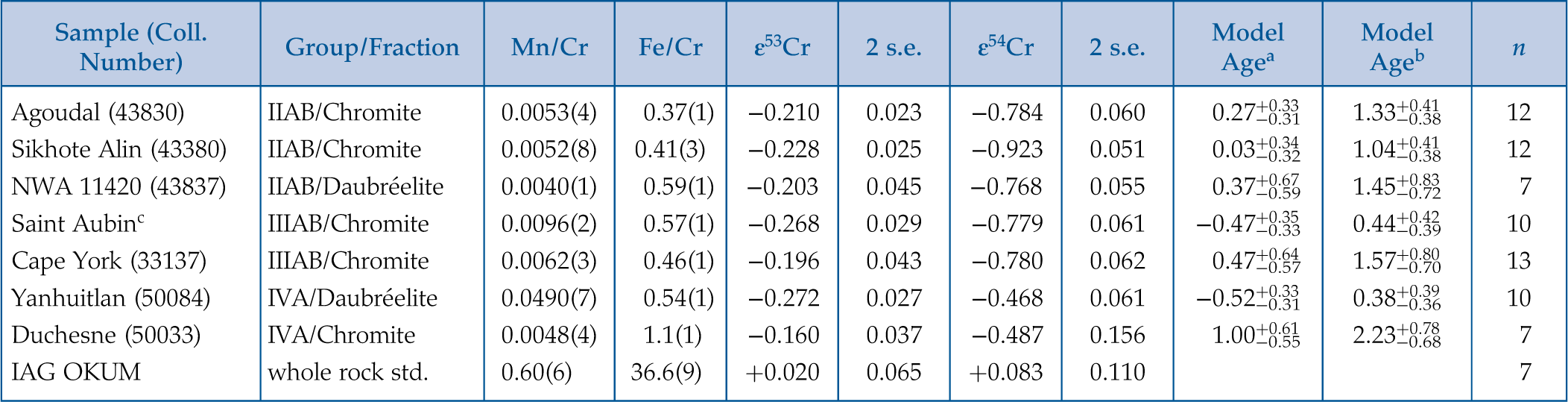

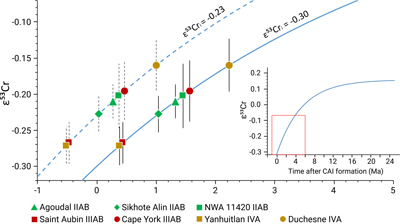

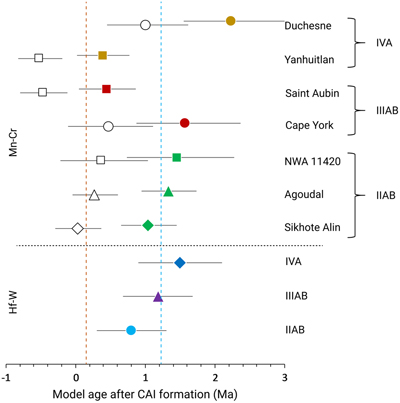

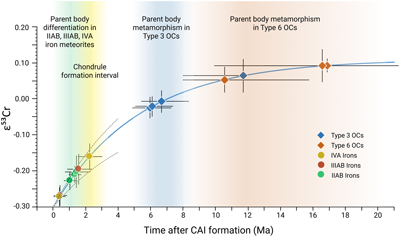

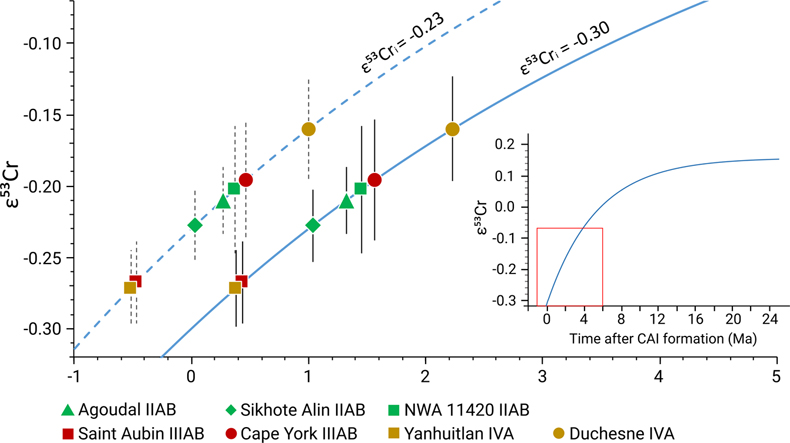

Figure 1 ɛ53Cr values of chromite/daubréelite plotted on a Cr isotope evolution curve determined for a chondritic reservoir through time using Equation 1. Error bars represent 2 s.e. uncertainties. |  Figure 2 Comparison between Mn–Cr (present study) and Hf–W (Kruijer et al., 2017) core formation ages. The Mn–Cr ages are determined using Equation 1 and ɛ53Cri = −0.23 (open symbols) from Trinquier et al. (2008) and ɛ53Cri = −0.30 (filled symbols) proposed in the present study. |  Figure 3 Timeline of early solar system formation showing parent body differentiation in magmatic iron meteorites, chondrule formation, and parent body metamorphism on ordinary chondrites (see text for references). Error envelope over iron meteorites shown by dashed lines represent the maximum variation in the evolutionary paths due to different Mn/Cr ratios of the parent bodies (see Fig. S-2). |  Table 1 Mn/Cr, Fe/Cr and Cr isotopic compositions of chromite and daubréelite fractions from iron meteorites. |

| Figure 1 | Figure 2 | Figure 3 | Table 1 |

top

Introduction

Members of the different magmatic iron meteorite groups are thought to sample the cores of distinct parent bodies that experienced large scale chemical fractionation, most notably metal–silicate separation. The absolute time of core formation provides a key time marker for the evolution of early formed planetesimals including accretion and cooling of the respective parent body. The most commonly used chronological system to date iron meteorites is the 182Hf–182W system (Kruijer et al., 2017

Kruijer, T.S., Burkhardt, C., Budde, G., Kleine, T. (2017) Age of Jupiter inferred from the distinct genetics and formation times of meteorites. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114, 6712–6716.

and references therein), constraining core formation in iron meteorite parent bodies over an interval of ∼1 Myr and their accretion to ∼0.1–0.3 Ma after the formation of Ca-Al-rich inclusions (4567.18 ± 0.50 Ma; Amelin et al., 2010Amelin, Y., Kaltenbach, A., Iizuka, T., Stirling, C.H., Ireland, T.R., Petaev, M., Jacobsen, S.B. (2010) U–Pb chronology of the Solar System’s oldest solids with variable 238U/235U. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 300, 343–350.

). These early accretion ages predate or are contemporaneous with the chondrule formation interval (e.g., Connelly et al., 2012Connelly, J.N., Bizzarro, M., Krot, A.N., Nordlund, Å., Wielandt, D., Ivanova, M.A. (2012) The absolute chronology and thermal processing of solids in the solar protoplanetary disk. Science 338, 651–655.

; Pape et al., 2019Pape, J., Mezger, K., Bouvier, A.S., Baumgartner, L.P. (2019) Time and duration of chondrule formation: Constraints from 26Al–26Mg ages of individual chondrules. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 244, 416–436.

). However, correct interpretation of Hf–W data depends on the accurate knowledge of initial ɛ182W of the solar system and Hf/W ratios of the parent bodies which are well established but still needs to consider possible variations in Hf isotopes due to galactic cosmic radiation (GCR) (Kruijer et al., 2017Kruijer, T.S., Burkhardt, C., Budde, G., Kleine, T. (2017) Age of Jupiter inferred from the distinct genetics and formation times of meteorites. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114, 6712–6716.

).Another powerful tool to constrain the time and duration of early solar system processes, including accretion, differentiation, metamorphism and subsequent cooling could be the short lived 53Mn–53Cr chronometer (t1/2 = 3.7 ± 0.4 Ma; Honda and Imamura, 1971

Honda, M., Imamura, M. (1971) Half-life of Mn53. Physical Review C 4, 1182–1188.

) (e.g., Shukolyukov and Lugmair, 2006Shukolyukov, A., Lugmair, G.W. (2006) Manganese–chromium isotope systematics of carbonaceous chondrites. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 250, 200–213.

; Trinquier et al., 2008Trinquier, A., Birck, J.L., Allègre, C.J., Göpel, C., Ulfbeck, D. (2008) 53Mn–53Cr systematics of the early Solar System revisited. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 72, 5146–5163.

; Göpel et al., 2015Göpel, C., Birck, J.L., Galy, A., Barrat, J.A., Zanda, B. (2015) Mn–Cr systematics in primitive meteorites: Insights from mineral separation and partial dissolution. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 156, 1–24.

; Zhu et al., 2021Zhu, K., Moynier, F., Schiller, M., Alexander, C.M.O’D., Davidson, J., Schrader, D.L., van Kooten, E., Bizzarro, M. (2021) Chromium isotopic insights into the origin of chondrite parent bodies and the early terrestrial volatile depletion. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 301, 158–186.

). Chromite (FeCr2O4) and daubréelite (FeCr2S4) are the two main carrier phases of Cr in magmatic iron meteorites. Both minerals have low Mn/Cr ratios (≤0.01; Duan and Regelous, 2014Duan, X., Regelous, M. (2014) Rapid determination of 26 elements in iron meteorites using matrix removal and membrane desolvating quadrupole ICP-MS. Journal of Analytical Atomic Spectrometry 29, 2379–2387.

) and thus preserve the Cr isotope composition of their growth environment at the time of isotopic closure, while the in-growth of radiogenic 53Cr from in situ decay of 53Mn is negligible (Anand et al., 2021Anand, A., Pape, J., Wille, M., Mezger, K. (2021) Chronological constraints on the thermal evolution of ordinary chondrite parent bodies from the 53Mn-53Cr system. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 307, 281–301.

). This makes them suitable for obtaining model ages by comparing their Cr isotopic composition with the Cr isotope evolution of the host reservoir. A particular advantage is that low Fe/Cr ratios in chromite and daubréelite (typically ∼0.5) result in negligible contribution of 53Cr produced by GCR from Fe; hence no correction for spallogenic Cr is required (Trinquier et al., 2008Trinquier, A., Birck, J.L., Allègre, C.J., Göpel, C., Ulfbeck, D. (2008) 53Mn–53Cr systematics of the early Solar System revisited. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 72, 5146–5163.

; Liu et al., 2019Liu, J., Qin, L., Xia, J., Carlson, R.W., Leya, I., Dauphas, N., He, Y. (2019) Cosmogenic effects on chromium isotopes in meteorites. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 251, 73–86.

) (Supplementary Information).This study presents model ages for chromite and daubréelite from the largest magmatic iron meteorite group collections (IIAB, IIIAB and IVA) that constrain the earliest stages of planetesimal formation and differentiation. These Cr model ages define the timing of metal segregation during core formation. Chromium-rich phases formed in the metal inherit the Cr isotope composition of their low Mn/Cr host and thus constrain the time of last silicate–metal equilibration.

top

Methods

A chromite or daubréelite fraction from seven iron meteorites was analysed. After mineral digestion and chemical purification, Cr isotopes were measured on a Triton™ Plus TIMS at the University of Bern. Each sample was measured on multiple filaments to achieve high precision for 53Cr/52Cr ratio. Isotope compositions are reported as parts per 10,000 deviations (ɛ notation) from the mean value of a terrestrial Cr standard measured along with the samples in each session. External precision (2 s.d.) for the terrestrial standard in a typical measurement session was ±0.1 for ɛ53Cr and ±0.2 for ɛ54Cr (Supplementary Information).

Model for ɛ53Cr evolution in chondritic reservoir. Model 53Cr/52Cr ages for early formed solar system bodies and their components can be determined on materials with high Cr/Mn and considering the following (i) homogeneous distribution of 53Mn in the solar system (e.g., Trinquier et al., 2008

Trinquier, A., Birck, J.L., Allègre, C.J., Göpel, C., Ulfbeck, D. (2008) 53Mn–53Cr systematics of the early Solar System revisited. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 72, 5146–5163.

; Zhu et al., 2019Zhu, K., Moynier, F., Wielandt, D., Larsen, K.K., Barrat, J.A., Bizzarro, M. (2019) Timing and Origin of the Angrite Parent Body Inferred from Cr Isotopes. The Astrophysical Journal 877, L13.

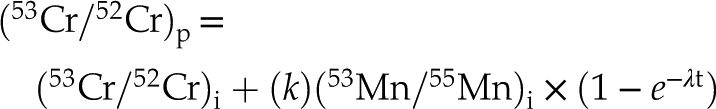

), (ii) known abundances of 53Mn and 53Cr at the beginning of the solar system (i.e. solar system initial ɛ53Cr) or any point in time thereafter, (iii) an estimate for the Mn/Cr in the relevant reservoir, and (iv) known decay constant of 53Mn. Based on these assumptions the evolution of the 53Cr/52Cr isotope composition of the chondritic reservoir through time can be expressed as:Eq. 1

where the subscripts ‘p’ and ‘i’ refer to the present day and initial solar system values, respectively, and λ denotes the 53Mn decay constant. The 55Mn/52Cr of the reservoir is denoted by k; and t represents the time elapsed since the start of the solar system, which is equated with the time of formation of CAIs. Equation 1 describes the evolution of 53Cr/52Cr with time for the chondritic reservoir and can be used to derive model ages for a meteorite sample by measuring the Cr isotopic composition of its chromite/daubréelite fraction.

top

Results

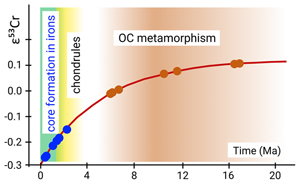

The ɛ53Cr and ɛ54Cr of chromite/daubréelite fractions determined for all samples are listed in Table 1. No correlation is observed in ɛ53Cr vs. ɛ54Cr and ɛ53Cr vs. Fe/Cr that corroborates an insignificant spallogenic contribution (Supplementary Information). Model ages are calculated relative to the CAI formation age of 4567.18 ± 0.50 Ma (Amelin et al., 2010

Amelin, Y., Kaltenbach, A., Iizuka, T., Stirling, C.H., Ireland, T.R., Petaev, M., Jacobsen, S.B. (2010) U–Pb chronology of the Solar System’s oldest solids with variable 238U/235U. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 300, 343–350.

) assuming an OC chondritic 55Mn/52Cr = 0.74 (Zhu et al., 2021Zhu, K., Moynier, F., Schiller, M., Alexander, C.M.O’D., Davidson, J., Schrader, D.L., van Kooten, E., Bizzarro, M. (2021) Chromium isotopic insights into the origin of chondrite parent bodies and the early terrestrial volatile depletion. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 301, 158–186.

), a solar system initial ɛ53Cr = −0.23 and a canonical 53Mn/55Mn = 6.28 × 10−6 (Trinquier et al., 2008Trinquier, A., Birck, J.L., Allègre, C.J., Göpel, C., Ulfbeck, D. (2008) 53Mn–53Cr systematics of the early Solar System revisited. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 72, 5146–5163.

) (Fig. 1).Table 1 Mn/Cr, Fe/Cr and Cr isotopic compositions of chromite and daubréelite fractions from iron meteorites.

| Sample (Coll. Number) | Group/Fraction | Mn/Cr | Fe/Cr | ɛ53Cr | 2 s.e. | ɛ54Cr | 2 s.e. | Model Agea | Model Ageb | n |

| Agoudal (43830) | IIAB/Chromite | 0.0053(4) | 0.37(1) | −0.210 | 0.023 | −0.784 | 0.060 | 0.27+0.33−0.31 | 1.33+0.41−0.38 | 12 |

| Sikhote Alin (43380) | IIAB/Chromite | 0.0052(8) | 0.41(3) | −0.228 | 0.025 | −0.923 | 0.051 | 0.03+0.34−0.32 | 1.04+0.41−0.38 | 12 |

| NWA 11420 (43837) | IIAB/Daubréelite | 0.0040(1) | 0.59(1) | −0.203 | 0.045 | −0.768 | 0.055 | 0.37+0.67−0.59 | 1.45+0.83−0.72 | 7 |

| Saint Aubinc | IIIAB/Chromite | 0.0096(2) | 0.57(1) | −0.268 | 0.029 | −0.779 | 0.061 | −0.47+0.35−0.33 | 0.44+0.42−0.39 | 10 |

| Cape York (33137) | IIIAB/Chromite | 0.0062(3) | 0.46(1) | −0.196 | 0.043 | −0.780 | 0.062 | 0.47+0.64−0.57 | 1.57+0.80−0.70 | 13 |

| Yanhuitlan (50084) | IVA/Daubréelite | 0.0490(7) | 0.54(1) | −0.272 | 0.027 | −0.468 | 0.061 | −0.52+0.33−0.31 | 0.38+0.39−0.36 | 10 |

| Duchesne (50033) | IVA/Chromite | 0.0048(4) | 1.1(1) | −0.160 | 0.037 | −0.487 | 0.156 | 1.00+0.61−0.55 | 2.23+0.78−0.68 | 7 |

| IAG OKUM | whole rock std. | 0.60(6) | 36.6(9) | +0.020 | 0.065 | +0.083 | 0.110 | 7 |

Collection numbers refer to meteorite collections of NHM Bern.

The uncertainties associated with Mn/Cr, Fe/Cr, and Cr isotopic compositions are reported as 2 s.e. of the replicate measurements. See Table S-1 for Cr isotopic composition of the individual runs. n = number of replicate measurements.

aEquation 1, ɛ53Cri = −0.23.

bEquation 1, ɛ53Cri = −0.30.

cNHM Vienna collection ID for Saint Aubin: NHMV_#13635_[A].

Figure 1 ɛ53Cr values of chromite/daubréelite plotted on a Cr isotope evolution curve determined for a chondritic reservoir through time using Equation 1. Error bars represent 2 s.e. uncertainties.

top

Discussion

The inference of Mn–Cr model ages to date core formation events is based on the assumption that metal–silicate separation was instantaneous. It occurred when the chondritic parent bodies of magmatic iron meteorites were heated by accretion energy and the decay of short lived 26Al, and reached the liquidus temperature of iron–sulfur alloy (1325 °C to 1615 °C, depending on the S content in the metal melt; Kaminski et al., 2020

Kaminski, E., Limare, A., Kenda, B., Chaussidon, M. (2020) Early accretion of planetesimals unraveled by the thermal evolution of the parent bodies of magmatic iron meteorites. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 548, 116469.

and references therein). The metal–silicate separation induced a strong chemical fractionation of Mn from the more siderophile Cr (Mann et al., 2009Mann, U., Frost, D.J., Rubie, D.C. (2009) Evidence for high-pressure core-mantle differentiation from the metal–silicate partitioning of lithophile and weakly-siderophile elements. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 73, 7360–7386.

). The measured low Mn/Cr (≤0.01; Duan and Regelous, 2014Duan, X., Regelous, M. (2014) Rapid determination of 26 elements in iron meteorites using matrix removal and membrane desolvating quadrupole ICP-MS. Journal of Analytical Atomic Spectrometry 29, 2379–2387.

) in iron meteorites corroborates the efficiency of this fractionation. Because of the low Mn/Cr of the metallic core, its Cr isotopic composition remained unchanged and reflects the composition at the time of metal–silicate differentiation. Therefore, the Cr isotopic composition of chromite/daubréelite that formed in the metallic core, no matter at what time after the metal segregation, reflects the time of Mn/Cr fractionation from a reservoir with CI chondritic 55Mn/52Cr and not the time of mineral formation nor its closure below a certain closure temperature.The Mn–Cr model ages determined using Equation 1. assume a Mn/Cr for the source reservoir that is represented by the average Mn/Cr of OCs. Ordinary chondrites have a CI-like Mn/Cr (e.g., Wasson and Allemeyn, 1988

Wasson, J.T., Allemeyn, G.W.K. (1988) Compositions of chondrites. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Mathematical and Physical Sciences 325, 535–544.

; Zhu et al., 2021Zhu, K., Moynier, F., Schiller, M., Alexander, C.M.O’D., Davidson, J., Schrader, D.L., van Kooten, E., Bizzarro, M. (2021) Chromium isotopic insights into the origin of chondrite parent bodies and the early terrestrial volatile depletion. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 301, 158–186.

) and alongside the investigated magmatic iron meteorite groups, belong to the ‘non-carbonaceous’ reservoir (Kleine et al., 2020Kleine, T., Budde, G., Burkhardt, C., Kruijer, T.S., Worsham, E.A., Morbidelli, A., Nimmo, F. (2020) The Non-carbonaceous–Carbonaceous Meteorite Dichotomy. Space Science Reviews 216, 1–27.

). The effect of different Mn/Cr of the iron meteorite parent bodies and the assumption of different initial ɛ53Cr is shown in Figure S-2. Model ages for IIAB, IIIAB and IVA groups are unaffected by the growth trajectory chosen, given current analytical resolution. Assuming a Mn/Cr similar to carbonaceous chondrites would change the model ages by a maximum of 1 Ma for the youngest sample. However, since all samples belong to the non-carbonaceous group, the average composition of OCs is most appropriate.Since the Cr isotopic composition of the samples is unaffected by contributions from spallogenic Cr (Supplementary Information), the only major source of uncertainty in Mn–Cr model ages comes from the choice of initial ɛ53Cr and 53Mn/55Mn values. Figure S-3 shows Mn–Cr model ages for the studied samples determined using initial Mn–Cr isotopic compositions from multiple studies reporting resolvable variations in the solar system initial ɛ53Cr and 53Mn/55Mn values. Clearly, more high precision Cr isotope data for samples dated with different chronometers are needed to further constrain the initial ɛ53Cr and 53Mn/55Mn. Model ages determined using initial ɛ53Cr and 53Mn/55Mn values from Göpel et al. (2015)

Göpel, C., Birck, J.L., Galy, A., Barrat, J.A., Zanda, B. (2015) Mn–Cr systematics in primitive meteorites: Insights from mineral separation and partial dissolution. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 156, 1–24.

and Shukolyukov and Lugmair (2006)Shukolyukov, A., Lugmair, G.W. (2006) Manganese–chromium isotope systematics of carbonaceous chondrites. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 250, 200–213.

predate the CAI formation age, contradicting the standard solar system model in which CAIs are the earliest formed solid objects. The Mn–Cr model ages determined using initial ɛ53Cr and 53Mn/55Mn from Trinquier et al. (2008)Trinquier, A., Birck, J.L., Allègre, C.J., Göpel, C., Ulfbeck, D. (2008) 53Mn–53Cr systematics of the early Solar System revisited. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 72, 5146–5163.

mostly postdate CAI formation and thus appear generally more reliable.The Mn–Cr model ages can also be compared with other chronometers that have been used to date meteorites and their components. 182Hf–182W, 207Pb–206Pb and 187Re–187Os are some of the common chronological systems providing constraints on different stages in the evolution of iron meteorite parent bodies (Goldstein et al., 2009

Goldstein, J.I., Scott, E.R.D., Chabot, N.L. (2009) Iron meteorites: Crystallization, thermal history, parent bodies, and origin. Geochemistry 69, 293–325.

and references therein). However, when applied to iron meteorites all other chronological systems date cooling below their respective isotopic closure with the exception of the 182Hf–182W system, which has strong similarities to the 53Mn–53Cr system. It is also suitable for examining the timescales and mechanisms of metal segregation for iron meteorite parent bodies since Hf and W have different geochemical behaviours resulting in strong Hf/W fractionation during metal/silicate separation (i.e. core formation). However, in addition to the uncertainty on the initial ɛ182W of the solar system, 182W/184W data are also affected by secondary neutron capture effects on W isotopes induced during cosmic ray exposure (unlike Mn–Cr model ages reported here). Recently, Pt isotope data have been used to quantify the effects of neutron capture on W isotope compositions, making it possible to produce more reliable core formation ages (e.g., Kruijer et al., 2017Kruijer, T.S., Burkhardt, C., Budde, G., Kleine, T. (2017) Age of Jupiter inferred from the distinct genetics and formation times of meteorites. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114, 6712–6716.

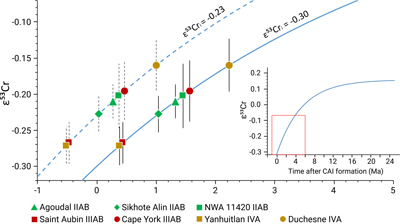

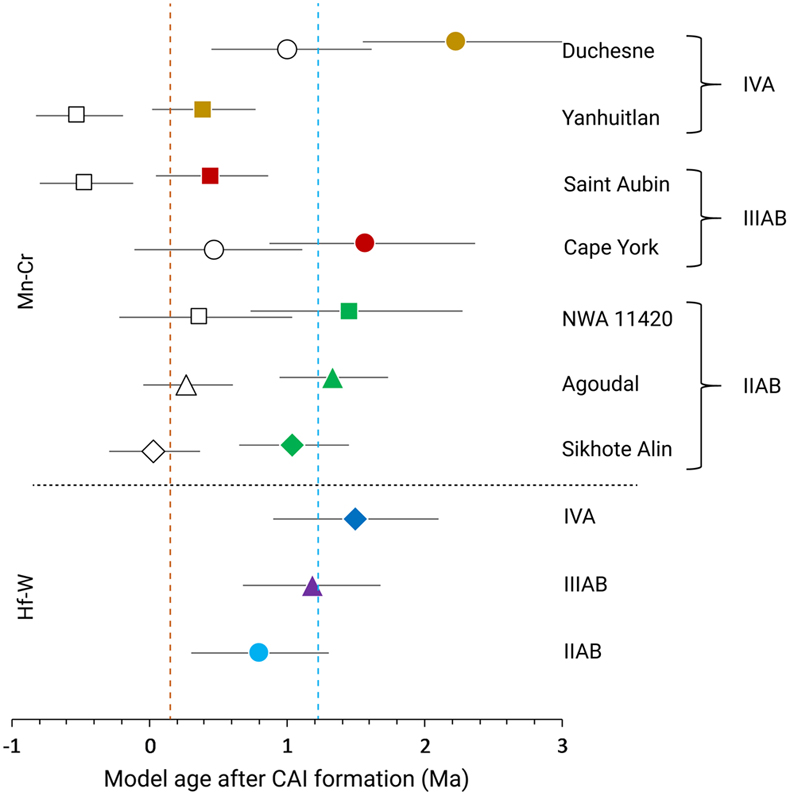

). The Mn–Cr core formation age corresponding to the weighted mean ɛ53Cr of combined IIAB, IIIAB and IVA groups determined using solar system initial ɛ53Cr = −0.23 (Trinquier et al., 2008Trinquier, A., Birck, J.L., Allègre, C.J., Göpel, C., Ulfbeck, D. (2008) 53Mn–53Cr systematics of the early Solar System revisited. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 72, 5146–5163.

) is ∼1 Myr older than the Hf–W core formation age corresponding to Pt corrected weighted mean ɛ182W of the same iron groups (Fig. 2, Table S-2) (Kruijer et al., 2017Kruijer, T.S., Burkhardt, C., Budde, G., Kleine, T. (2017) Age of Jupiter inferred from the distinct genetics and formation times of meteorites. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114, 6712–6716.

). However, the Hf–W and Mn–Cr systems show consistent crystallisation ages in angrites (internal isochrons established by minerals) that also belong to the ‘non-carbonaceous’ reservoir and originated from differentiated parent bodies (Zhu et al., 2019Zhu, K., Moynier, F., Wielandt, D., Larsen, K.K., Barrat, J.A., Bizzarro, M. (2019) Timing and Origin of the Angrite Parent Body Inferred from Cr Isotopes. The Astrophysical Journal 877, L13.

). The different chronometers are expected to agree because of the rapid cooling of angrites indicated by their basaltic texture. A better fit between Hf–W and Cr model ages can be obtained when the uncertainties on the model parameters for Mn–Cr model age determination are considered. Uncertainties on the 53Mn decay constant (Honda and Imamura, 1971Honda, M., Imamura, M. (1971) Half-life of Mn53. Physical Review C 4, 1182–1188.

) and solar system 53Mn/55Mn (Trinquier et al., 2008Trinquier, A., Birck, J.L., Allègre, C.J., Göpel, C., Ulfbeck, D. (2008) 53Mn–53Cr systematics of the early Solar System revisited. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 72, 5146–5163.

) result in only a minor shift in the model ages of generally <0.02 Myr which is insignificant. However, using a solar system initial ɛ53Cr = −0.30, which is within its reported uncertainty (ɛ53Cr = −0.23 ± 0.09; Trinquier et al., 2008Trinquier, A., Birck, J.L., Allègre, C.J., Göpel, C., Ulfbeck, D. (2008) 53Mn–53Cr systematics of the early Solar System revisited. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 72, 5146–5163.

), results in a perfect fit with the mean 182Hf–182W model ages for magmatic iron meteorite groups (Fig. 2). Consequently, ɛ53Cr = −0.30 is proposed as a better estimate for the solar system initial ɛ53Cr. To maintain a match between Hf–W and Mn–Cr model ages the uncertainty on the initial ɛ53Cr of the solar system is less than ±0.05.

Figure 2 Comparison between Mn–Cr (present study) and Hf–W (Kruijer et al., 2017

Kruijer, T.S., Burkhardt, C., Budde, G., Kleine, T. (2017) Age of Jupiter inferred from the distinct genetics and formation times of meteorites. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114, 6712–6716.

) core formation ages. The Mn–Cr ages are determined using Equation 1 and ɛ53Cri = −0.23 (open symbols) from Trinquier et al. (2008)Trinquier, A., Birck, J.L., Allègre, C.J., Göpel, C., Ulfbeck, D. (2008) 53Mn–53Cr systematics of the early Solar System revisited. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 72, 5146–5163.

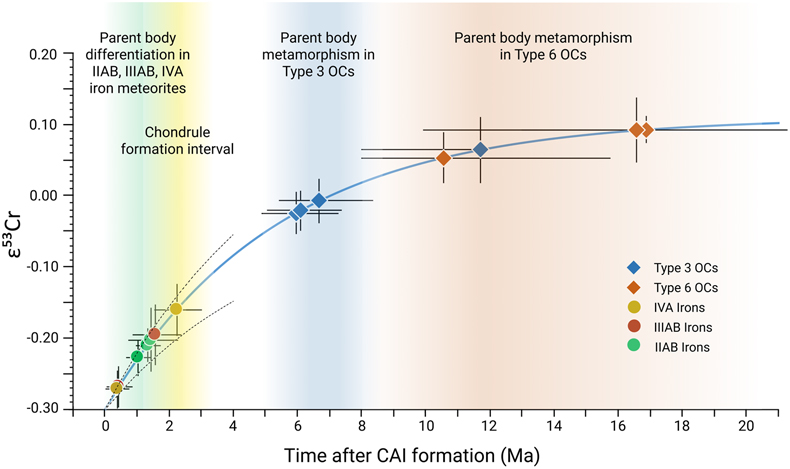

and ɛ53Cri = −0.30 (filled symbols) proposed in the present study.Figure 3 presents a timeline depicting chromite/daubréelite model ages for IIAB, IIIAB and IVA iron meteorites and parent body metamorphism ages for type 3 and 6 ordinary chondrites as determined in Anand et al. (2021)

Anand, A., Pape, J., Wille, M., Mezger, K. (2021) Chronological constraints on the thermal evolution of ordinary chondrite parent bodies from the 53Mn-53Cr system. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 307, 281–301.

using updated parameters for model age calculation. Combined with the existing thermal models (e.g., Qin et al., 2008Qin, L., Dauphas, N., Wadhwa, M., Masarik, J., Janney, P.E. (2008) Rapid accretion and differentiation of iron meteorite parent bodies inferred from 182Hf–182W chronometry and thermal modeling. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 273, 94–104.

), Hf–W core formation ages and calibrated Mn–Cr model ages constrain the accretion of the magmatic iron meteorite parent bodies to within less than 1 Myr and no later than 1.5 Myr after CAI formation. This is in perfect agreement with numerical simulations that require early and efficient accretion of larger bodies within the protoplanetary disk (e.g., Johansen et al., 2007Johansen, A., Oishi, J.S., Mac Low, M.M., Klahr, H., Henning, T., Youdin, A. (2007) Rapid planetesimal formation in turbulent circumstellar disks. Nature 448, 1022–1025.

; Cuzzi et al., 2008Cuzzi, J.N., Hogan, R.C., Shariff, K. (2008) Towards planetesimals: Dense chondrule clumps in the protoplanetary nebula. The Astrophysical Journal 687, 1432–1447.

). The small spread in the model ages of samples from the same meteorite group might reflect some core–mantle exchange during the solidification of the metal core. The range is similar to the range of individual Hf–W model ages within an iron-meteorite group (e.g., Kruijer et al., 2017Kruijer, T.S., Burkhardt, C., Budde, G., Kleine, T. (2017) Age of Jupiter inferred from the distinct genetics and formation times of meteorites. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114, 6712–6716.

).

Figure 3 Timeline of early solar system formation showing parent body differentiation in magmatic iron meteorites, chondrule formation, and parent body metamorphism on ordinary chondrites (see text for references). Error envelope over iron meteorites shown by dashed lines represent the maximum variation in the evolutionary paths due to different Mn/Cr ratios of the parent bodies (see Fig. S-2).

One of the most important implications of Mn–Cr and Hf–W (e.g., Kruijer et al., 2017

Kruijer, T.S., Burkhardt, C., Budde, G., Kleine, T. (2017) Age of Jupiter inferred from the distinct genetics and formation times of meteorites. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114, 6712–6716.

; Spitzer et al., 2021Spitzer, F., Burkhardt, C., Nimmo, F., Kleine, T. (2021) Nucleosynthetic Pt isotope anomalies and the Hf–W chronology of core formation in inner and outer solar system planetesimals. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 576, 117211.

) core formation ages is that they bring the accretion and differentiation of the magmatic iron meteorite parent bodies in context with the chondrule formation interval recorded in chondrite samples (e.g., Connelly et al., 2012Connelly, J.N., Bizzarro, M., Krot, A.N., Nordlund, Å., Wielandt, D., Ivanova, M.A. (2012) The absolute chronology and thermal processing of solids in the solar protoplanetary disk. Science 338, 651–655.

; Pape et al., 2019Pape, J., Mezger, K., Bouvier, A.S., Baumgartner, L.P. (2019) Time and duration of chondrule formation: Constraints from 26Al–26Mg ages of individual chondrules. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 244, 416–436.

, 2021Pape, J., Rosén, V., Mezger, K., Guillong, M. (2021) Primary crystallization and partial remelting of chondrules in the protoplanetary disk: Petrographic, mineralogical and chemical constraints recorded in zoned type-I chondrules. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 292, 499–517.

). 207Pb–206Pb chondrule formation ages (Connelly et al., 2012Connelly, J.N., Bizzarro, M., Krot, A.N., Nordlund, Å., Wielandt, D., Ivanova, M.A. (2012) The absolute chronology and thermal processing of solids in the solar protoplanetary disk. Science 338, 651–655.

) suggest that the production of chondrules began as early as the CAI condensation; hence, contemporaneous with the accretion of the parent bodies of magmatic iron meteorites as suggested by Hf–W core formation ages and collaborated by Mn–Cr model ages in the present study. 26Al–26Mg ages for the formation of melt in individual chondrules, as summarised in Pape et al. (2019)Pape, J., Mezger, K., Bouvier, A.S., Baumgartner, L.P. (2019) Time and duration of chondrule formation: Constraints from 26Al–26Mg ages of individual chondrules. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 244, 416–436.

, suggest that chondrule formation in ordinary and most carbonaceous chondrites lasted from ca. 1.8–3.0 Ma with a major phase around 2.0–2.3 Ma after CAI formation. This puts the chondrule formation interval after the accretion of the magmatic iron meteorite parent bodies. The latter implies that chondrule formation may not necessarily be an intermediate step on the way from dust to planets, but rather early planet formation may have been the cause for the chondrule formation at least in extant chondrite samples. Thus, the early planetesimal formation (i.e. accretion of the iron meteorites parent bodies) was a local process and happened while other regions were still mostly in the stage of accreting dust particles and chondrule formation.top

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the support through a ‘Swiss Government Excellence Scholarship (2018.0371)’ and NCCR PlanetS supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation grant no. 51NF40-141881. We thank Dr. Ludovic Ferriere from NHM Vienna for providing chromite from Saint Aubin meteorite. Dr. Harry Becker and Smithsonian Institution are thanked for providing Allende powder sample. Patrick Neuhaus and Lorenz Gfeller from the Institute of Geography, University of Bern, are thanked for assistance with the ICP-MS analysis of the samples. We thank Dr. Maud Boyet for editorial handling and Dr. Ke Zhu and an anonymous reviewer for their constructive comments that helped to improve the manuscript.

Editor: Maud Boyet

top

References

Amelin, Y., Kaltenbach, A., Iizuka, T., Stirling, C.H., Ireland, T.R., Petaev, M., Jacobsen, S.B. (2010) U–Pb chronology of the Solar System’s oldest solids with variable 238U/235U. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 300, 343–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2010.10.015

Show in context

Show in context Model ages are calculated relative to the CAI formation age of 4567.18 ± 0.50 Ma (Amelin et al., 2010) assuming an OC chondritic 55Mn/52Cr = 0.74 (Zhu et al., 2021), a solar system initial ɛ53Cr = −0.23 and a canonical 53Mn/55Mn = 6.28 × 10−6 (Trinquier et al., 2008) (Fig. 1).

View in article

The most commonly used chronological system to date iron meteorites is the 182Hf–182W system (Kruijer et al., 2017 and references therein), constraining core formation in iron meteorite parent bodies over an interval of ∼1 Myr and their accretion to ∼0.1–0.3 Ma after the formation of Ca-Al-rich inclusions (4567.18 ± 0.50 Ma; Amelin et al., 2010).

View in article

Anand, A., Pape, J., Wille, M., Mezger, K. (2021) Chronological constraints on the thermal evolution of ordinary chondrite parent bodies from the 53Mn-53Cr system. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 307, 281–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2021.04.029

Show in context

Show in context Figure 3 presents a timeline depicting chromite/daubréelite model ages for IIAB, IIIAB and IVA iron meteorites and parent body metamorphism ages for type 3 and 6 ordinary chondrites as determined in Anand et al. (2021) using updated parameters for model age calculation. Combined with the existing thermal models (e.g., Qin et al., 2008), Hf–W core formation ages and calibrated Mn–Cr model ages constrain the accretion of the magmatic iron meteorite parent bodies to within less than 1 Myr and no later than 1.5 Myr after CAI formation.

View in article

Chromite (FeCr2O4) and daubréelite (FeCr2S4) are the two main carrier phases of Cr in magmatic iron meteorites. Both minerals have low Mn/Cr ratios (≤0.01; Duan and Regelous, 2014) and thus preserve the Cr isotope composition of their growth environment at the time of isotopic closure, while the in-growth of radiogenic 53Cr from in situ decay of 53Mn is negligible (Anand et al., 2021).

View in article

Connelly, J.N., Bizzarro, M., Krot, A.N., Nordlund, Å., Wielandt, D., Ivanova, M.A. (2012) The absolute chronology and thermal processing of solids in the solar protoplanetary disk. Science 338, 651–655. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1226919

Show in context

Show in context These early accretion ages predate or are contemporaneous with the chondrule formation interval (e.g., Connelly et al., 2012; Pape et al., 2019).

View in article

207Pb–206Pb chondrule formation ages (Connelly et al., 2012) suggest that the production of chondrules began as early as the CAI condensation; hence, contemporaneous with the accretion of the parent bodies of magmatic iron meteorites as suggested by Hf–W core formation ages and collaborated by Mn–Cr model ages in the present study.

View in article

One of the most important implications of Mn–Cr and Hf–W (e.g., Kruijer et al., 2017; Spitzer et al., 2021) core formation ages is that they bring the accretion and differentiation of the magmatic iron meteorite parent bodies in context with the chondrule formation interval recorded in chondrite samples (e.g., Connelly et al., 2012; Pape et al., 2019, 2021).

View in article

Cuzzi, J.N., Hogan, R.C., Shariff, K. (2008) Towards planetesimals: Dense chondrule clumps in the protoplanetary nebula. The Astrophysical Journal 687, 1432–1447. https://doi.org/10.1086/591239

Show in context

Show in context This is in perfect agreement with numerical simulations that require early and efficient accretion of larger bodies within the protoplanetary disk (e.g., Johansen et al., 2007; Cuzzi et al., 2008).

View in article

Duan, X., Regelous, M. (2014) Rapid determination of 26 elements in iron meteorites using matrix removal and membrane desolvating quadrupole ICP-MS. Journal of Analytical Atomic Spectrometry 29, 2379–2387. https://doi.org/10.1039/C4JA00244J

Show in context

Show in context The measured low Mn/Cr (≤0.01; Duan and Regelous, 2014) in iron meteorites corroborates the efficiency of this fractionation. Because of the low Mn/Cr of the metallic core, its Cr isotopic composition remained unchanged and reflects the composition at the time of metal–silicate differentiation.

View in article

Chromite (FeCr2O4) and daubréelite (FeCr2S4) are the two main carrier phases of Cr in magmatic iron meteorites. Both minerals have low Mn/Cr ratios (≤0.01; Duan and Regelous, 2014) and thus preserve the Cr isotope composition of their growth environment at the time of isotopic closure, while the in-growth of radiogenic 53Cr from in situ decay of 53Mn is negligible (Anand et al., 2021).

View in article

Goldstein, J.I., Scott, E.R.D., Chabot, N.L. (2009) Iron meteorites: Crystallization, thermal history, parent bodies, and origin. Geochemistry 69, 293–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemer.2009.01.002

Show in context

Show in context 182Hf–182W, 207Pb–206Pb and 187Re–187Os are some of the common chronological systems providing constraints on different stages in the evolution of iron meteorite parent bodies (Goldstein et al., 2009 and references therein).

View in article

182Hf–182W, 207Pb–206Pb and 187Re–187Os are some of the common chronological systems providing constraints on different stages in the evolution of iron meteorite parent bodies (Goldstein et al., 2009 and references therein).

View in article

Göpel, C., Birck, J.L., Galy, A., Barrat, J.A., Zanda, B. (2015) Mn–Cr systematics in primitive meteorites: Insights from mineral separation and partial dissolution. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 156, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2015.02.008

Show in context

Show in context Model ages determined using initial ɛ53Cr and 53Mn/55Mn values from Göpel et al. (2015) and Shukolyukov and Lugmair (2006) predate the CAI formation age, contradicting the standard solar system model in which CAIs are the earliest formed solid objects.

View in article

Another powerful tool to constrain the time and duration of early solar system processes, including accretion, differentiation, metamorphism and subsequent cooling could be the short lived 53Mn–53Cr chronometer (t1/2 = 3.7 ± 0.4 Ma; Honda and Imamura, 1971) (e.g., Shukolyukov and Lugmair, 2006; Trinquier et al., 2008; Göpel et al., 2015; Zhu et al., 2021).

View in article

Honda, M., Imamura, M. (1971) Half-life of Mn53. Physical Review C 4, 1182–1188. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.4.1182

Show in context

Show in context Another powerful tool to constrain the time and duration of early solar system processes, including accretion, differentiation, metamorphism and subsequent cooling could be the short lived 53Mn–53Cr chronometer (t1/2 = 3.7 ± 0.4 Ma; Honda and Imamura, 1971) (e.g., Shukolyukov and Lugmair, 2006; Trinquier et al., 2008; Göpel et al., 2015; Zhu et al., 2021).

View in article

Uncertainties on the 53Mn decay constant (Honda and Imamura, 1971) and solar system 53Mn/55Mn (Trinquier et al., 2008) result in only a minor shift in the model ages of generally <0.02 Myr which is insignificant.

View in article

Johansen, A., Oishi, J.S., Mac Low, M.M., Klahr, H., Henning, T., Youdin, A. (2007) Rapid planetesimal formation in turbulent circumstellar disks. Nature 448, 1022–1025. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature06086

Show in context

Show in context This is in perfect agreement with numerical simulations that require early and efficient accretion of larger bodies within the protoplanetary disk (e.g., Johansen et al., 2007; Cuzzi et al., 2008).

View in article

Kaminski, E., Limare, A., Kenda, B., Chaussidon, M. (2020) Early accretion of planetesimals unraveled by the thermal evolution of the parent bodies of magmatic iron meteorites. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 548, 116469. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2020.116469

Show in context

Show in context It occurred when the chondritic parent bodies of magmatic iron meteorites were heated by accretion energy and the decay of short lived 26Al, and reached the liquidus temperature of iron–sulfur alloy (1325 °C to 1615 °C, depending on the S content in the metal melt; Kaminski et al., 2020 and references therein).

View in article

Kleine, T., Budde, G., Burkhardt, C., Kruijer, T.S., Worsham, E.A., Morbidelli, A., Nimmo, F. (2020) The Non-carbonaceous–Carbonaceous Meteorite Dichotomy. Space Science Reviews 216, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11214-020-00675-w

Show in context

Show in context Ordinary chondrites have a CI-like Mn/Cr (e.g., Wasson and Allemeyn, 1988; Zhu et al., 2021) and alongside the investigated magmatic iron meteorite groups, belong to the ‘non-carbonaceous’ reservoir (Kleine et al., 2020).

View in article

Kruijer, T.S., Burkhardt, C., Budde, G., Kleine, T. (2017) Age of Jupiter inferred from the distinct genetics and formation times of meteorites. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114, 6712–6716. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1704461114

Show in context

Show in context However, correct interpretation of Hf–W data depends on the accurate knowledge of initial ɛ182W of the solar system and Hf/W ratios of the parent bodies which are well established but still needs to consider possible variations in Hf isotopes due to galactic cosmic radiation (GCR) (Kruijer et al., 2017).

View in article

Recently, Pt isotope data have been used to quantify the effects of neutron capture on W isotope compositions, making it possible to produce more reliable core formation ages (e.g., Kruijer et al., 2017).

View in article

The most commonly used chronological system to date iron meteorites is the 182Hf–182W system (Kruijer et al., 2017 and references therein), constraining core formation in iron meteorite parent bodies over an interval of ∼1 Myr and their accretion to ∼0.1–0.3 Ma after the formation of Ca-Al-rich inclusions (4567.18 ± 0.50 Ma; Amelin et al., 2010).

View in article

Comparison between Mn–Cr (present study) and Hf–W (Kruijer et al., 2017) core formation ages.

View in article

The range is similar to the range of individual Hf–W model ages within an iron-meteorite group (e.g., Kruijer et al., 2017).

View in article

One of the most important implications of Mn–Cr and Hf–W (e.g., Kruijer et al., 2017; Spitzer et al., 2021) core formation ages is that they bring the accretion and differentiation of the magmatic iron meteorite parent bodies in context with the chondrule formation interval recorded in chondrite samples (e.g., Connelly et al., 2012; Pape et al., 2019, 2021).

View in article

The Mn–Cr core formation age corresponding to the weighted mean ɛ53Cr of combined IIAB, IIIAB and IVA groups determined using solar system initial ɛ53Cr = −0.23 (Trinquier et al., 2008) is ∼1 Myr older than the Hf–W core formation age corresponding to Pt corrected weighted mean ɛ182W of the same iron groups (Fig. 2, Table S-2) (Kruijer et al., 2017).

View in article

Liu, J., Qin, L., Xia, J., Carlson, R.W., Leya, I., Dauphas, N., He, Y. (2019) Cosmogenic effects on chromium isotopes in meteorites. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 251, 73–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2019.01.032

Show in context

Show in context A particular advantage is that low Fe/Cr ratios in chromite and daubréelite (typically ∼0.5) result in negligible contribution of 53Cr produced by GCR from Fe; hence no correction for spallogenic Cr is required (Trinquier et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2019) (Supplementary Information).

View in article

Mann, U., Frost, D.J., Rubie, D.C. (2009) Evidence for high-pressure core-mantle differentiation from the metal–silicate partitioning of lithophile and weakly-siderophile elements. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 73, 7360–7386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2009.08.006

Show in context

Show in context The metal–silicate separation induced a strong chemical fractionation of Mn from the more siderophile Cr (Mann et al., 2009).

View in article

Pape, J., Mezger, K., Bouvier, A.S., Baumgartner, L.P. (2019) Time and duration of chondrule formation: Constraints from 26Al–26Mg ages of individual chondrules. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 244, 416–436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2018.10.017

Show in context

Show in context These early accretion ages predate or are contemporaneous with the chondrule formation interval (e.g., Connelly et al., 2012; Pape et al., 2019).

View in article

26Al–26Mg ages for the formation of melt in individual chondrules, as summarised in Pape et al. (2019), suggest that chondrule formation in ordinary and most carbonaceous chondrites lasted from ca. 1.8–3.0 Ma with a major phase around 2.0–2.3 Ma after CAI formation.

View in article

One of the most important implications of Mn–Cr and Hf–W (e.g., Kruijer et al., 2017; Spitzer et al., 2021) core formation ages is that they bring the accretion and differentiation of the magmatic iron meteorite parent bodies in context with the chondrule formation interval recorded in chondrite samples (e.g., Connelly et al., 2012; Pape et al., 2019, 2021).

View in article

Pape, J., Rosén, V., Mezger, K., Guillong, M. (2021) Primary crystallization and partial remelting of chondrules in the protoplanetary disk: Petrographic, mineralogical and chemical constraints recorded in zoned type-I chondrules. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 292, 499–517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2020.10.019

Show in context

Show in context One of the most important implications of Mn–Cr and Hf–W (e.g., Kruijer et al., 2017; Spitzer et al., 2021) core formation ages is that they bring the accretion and differentiation of the magmatic iron meteorite parent bodies in context with the chondrule formation interval recorded in chondrite samples (e.g., Connelly et al., 2012; Pape et al., 2019, 2021).

View in article

Qin, L., Dauphas, N., Wadhwa, M., Masarik, J., Janney, P.E. (2008) Rapid accretion and differentiation of iron meteorite parent bodies inferred from 182Hf–182W chronometry and thermal modeling. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 273, 94–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2008.06.018

Show in context

Show in context Figure 3 presents a timeline depicting chromite/daubréelite model ages for IIAB, IIIAB and IVA iron meteorites and parent body metamorphism ages for type 3 and 6 ordinary chondrites as determined in Anand et al. (2021) using updated parameters for model age calculation. Combined with the existing thermal models (e.g., Qin et al., 2008), Hf–W core formation ages and calibrated Mn–Cr model ages constrain the accretion of the magmatic iron meteorite parent bodies to within less than 1 Myr and no later than 1.5 Myr after CAI formation.

View in article

Shukolyukov, A., Lugmair, G.W. (2006) Manganese–chromium isotope systematics of carbonaceous chondrites. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 250, 200–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2006.07.036

Show in context

Show in context Another powerful tool to constrain the time and duration of early solar system processes, including accretion, differentiation, metamorphism and subsequent cooling could be the short lived 53Mn–53Cr chronometer (t1/2 = 3.7 ± 0.4 Ma; Honda and Imamura, 1971) (e.g., Shukolyukov and Lugmair, 2006; Trinquier et al., 2008; Göpel et al., 2015; Zhu et al., 2021).

View in article

Model ages determined using initial ɛ53Cr and 53Mn/55Mn values from Göpel et al. (2015) and Shukolyukov and Lugmair (2006) predate the CAI formation age, contradicting the standard solar system model in which CAIs are the earliest formed solid objects.

View in article

Spitzer, F., Burkhardt, C., Nimmo, F., Kleine, T. (2021) Nucleosynthetic Pt isotope anomalies and the Hf–W chronology of core formation in inner and outer solar system planetesimals. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 576, 117211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2021.117211

Show in context

Show in context One of the most important implications of Mn–Cr and Hf–W (e.g., Kruijer et al., 2017; Spitzer et al., 2021) core formation ages is that they bring the accretion and differentiation of the magmatic iron meteorite parent bodies in context with the chondrule formation interval recorded in chondrite samples (e.g., Connelly et al., 2012; Pape et al., 2019, 2021).

View in article

Trinquier, A., Birck, J.L., Allègre, C.J., Göpel, C., Ulfbeck, D. (2008) 53Mn–53Cr systematics of the early Solar System revisited. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 72, 5146–5163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2008.03.023

Show in context

Show in context A particular advantage is that low Fe/Cr ratios in chromite and daubréelite (typically ∼0.5) result in negligible contribution of 53Cr produced by GCR from Fe; hence no correction for spallogenic Cr is required (Trinquier et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2019) (Supplementary Information).

View in article

Model 53Cr/52Cr ages for early formed solar system bodies and their components can be determined on materials with high Cr/Mn and considering the following (i) homogeneous distribution of 53Mn in the solar system (e.g., Trinquier et al., 2008; Zhu et al., 2019), (ii) known abundances of 53Mn and 53Cr at the beginning of the solar system (i.e. solar system initial ɛ53Cr) or any point in time thereafter, (iii) an estimate for the Mn/Cr in the relevant reservoir, and (iv) known decay constant of 53Mn.

View in article

The Mn–Cr model ages determined using initial ɛ53Cr and 53Mn/55Mn from Trinquier et al. (2008) mostly postdate CAI formation and thus appear generally more reliable.

View in article

The Mn–Cr core formation age corresponding to the weighted mean ɛ53Cr of combined IIAB, IIIAB and IVA groups determined using solar system initial ɛ53Cr = −0.23 (Trinquier et al., 2008) is ∼1 Myr older than the Hf–W core formation age corresponding to Pt corrected weighted mean ɛ182W of the same iron groups (Fig. 2, Table S-2) (Kruijer et al., 2017).

View in article

Uncertainties on the 53Mn decay constant (Honda and Imamura, 1971) and solar system 53Mn/55Mn (Trinquier et al., 2008) result in only a minor shift in the model ages of generally <0.02 Myr which is insignificant.

View in article

However, using a solar system initial ɛ53Cr = −0.30, which is within its reported uncertainty (ɛ53Cr = −0.23 ± 0.09; Trinquier et al., 2008), results in a perfect fit with the mean 182Hf–182W model ages for magmatic iron meteorite groups (Fig. 2).

View in article

The Mn–Cr ages are determined using Equation 1 and ɛ53Cri = −0.23 (open symbols) from Trinquier et al. (2008) and ɛ53Cri = −0.30 (filled symbols) proposed in the present study.

View in article

Model ages are calculated relative to the CAI formation age of 4567.18 ± 0.50 Ma (Amelin et al., 2010) assuming an OC chondritic 55Mn/52Cr = 0.74 (Zhu et al., 2021), a solar system initial ɛ53Cr = −0.23 and a canonical 53Mn/55Mn = 6.28 × 10−6 (Trinquier et al., 2008) (Fig. 1).

View in article

Wasson, J.T., Allemeyn, G.W.K. (1988) Compositions of chondrites. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Mathematical and Physical Sciences 325, 535–544. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.1988.0066

Show in context

Show in context Ordinary chondrites have a CI-like Mn/Cr (e.g., Wasson and Allemeyn, 1988; Zhu et al., 2021) and alongside the investigated magmatic iron meteorite groups, belong to the ‘non-carbonaceous’ reservoir (Kleine et al., 2020).

View in article

Zhu, K., Moynier, F., Wielandt, D., Larsen, K.K., Barrat, J.A., Bizzarro, M. (2019) Timing and Origin of the Angrite Parent Body Inferred from Cr Isotopes. The Astrophysical Journal 877, L13. https://doi.org/10.3847/2041-8213/ab2044

Show in context

Show in context However, the Hf–W and Mn–Cr systems show consistent crystallisation ages in angrites (internal isochrons established by minerals) that also belong to the ‘non-carbonaceous’ reservoir and originated from differentiated parent bodies (Zhu et al., 2019).

View in article

Model 53Cr/52Cr ages for early formed solar system bodies and their components can be determined on materials with high Cr/Mn and considering the following (i) homogeneous distribution of 53Mn in the solar system (e.g., Trinquier et al., 2008; Zhu et al., 2019), (ii) known abundances of 53Mn and 53Cr at the beginning of the solar system (i.e. solar system initial ɛ53Cr) or any point in time thereafter, (iii) an estimate for the Mn/Cr in the relevant reservoir, and (iv) known decay constant of 53Mn.

View in article

Zhu, K., Moynier, F., Schiller, M., Alexander, C.M.O’D., Davidson, J., Schrader, D.L., van Kooten, E., Bizzarro, M. (2021) Chromium isotopic insights into the origin of chondrite parent bodies and the early terrestrial volatile depletion. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 301, 158–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2021.02.031

Show in context

Show in context Model ages are calculated relative to the CAI formation age of 4567.18 ± 0.50 Ma (Amelin et al., 2010) assuming an OC chondritic 55Mn/52Cr = 0.74 (Zhu et al., 2021), a solar system initial ɛ53Cr = −0.23 and a canonical 53Mn/55Mn = 6.28 × 10−6 (Trinquier et al., 2008) (Fig. 1).

View in article

Ordinary chondrites have a CI-like Mn/Cr (e.g., Wasson and Allemeyn, 1988; Zhu et al., 2021) and alongside the investigated magmatic iron meteorite groups, belong to the ‘non-carbonaceous’ reservoir (Kleine et al., 2020).

View in article

Another powerful tool to constrain the time and duration of early solar system processes, including accretion, differentiation, metamorphism and subsequent cooling could be the short lived 53Mn–53Cr chronometer (t1/2 = 3.7 ± 0.4 Ma; Honda and Imamura, 1971) (e.g., Shukolyukov and Lugmair, 2006; Trinquier et al., 2008; Göpel et al., 2015; Zhu et al., 2021).

View in article

top

Supplementary Information

The Supplementary Information includes:

- 1. Samples and Analytical Methods

- 2. Precision and Accuracy of Cr Isotope Data

- 3. Correction for Spallogenic Cr

- 4. Summary of (53Mn/55Mn)i and ɛ53Cri

- Tables S-1 to S-3

- Figures S-1 to S-3

- Supplementary Information References

Download the Supplementary Information (PDF).

Figures

Figure 1 ɛ53Cr values of chromite/daubréelite plotted on a Cr isotope evolution curve determined for a chondritic reservoir through time using Equation 1. Error bars represent 2 s.e. uncertainties.

Figure 2 Comparison between Mn–Cr (present study) and Hf–W (Kruijer et al., 2017

Kruijer, T.S., Burkhardt, C., Budde, G., Kleine, T. (2017) Age of Jupiter inferred from the distinct genetics and formation times of meteorites. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114, 6712–6716.

) core formation ages. The Mn–Cr ages are determined using Equation 1 and ɛ53Cri = −0.23 (open symbols) from Trinquier et al. (2008)Trinquier, A., Birck, J.L., Allègre, C.J., Göpel, C., Ulfbeck, D. (2008) 53Mn–53Cr systematics of the early Solar System revisited. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 72, 5146–5163.

and ɛ53Cri = −0.30 (filled symbols) proposed in the present study.

Figure 3 Timeline of early solar system formation showing parent body differentiation in magmatic iron meteorites, chondrule formation, and parent body metamorphism on ordinary chondrites (see text for references). Error envelope over iron meteorites shown by dashed lines represent the maximum variation in the evolutionary paths due to different Mn/Cr ratios of the parent bodies (see Fig. S-2).