Interaction between clay minerals and organics in asteroid Ryugu

Affiliations | Corresponding Author | Cite as | Funding information- Share this article

-

Article views:185Cumulative count of HTML views and PDF downloads.

- Download Citation

- Rights & Permissions

top

Abstract

Figures

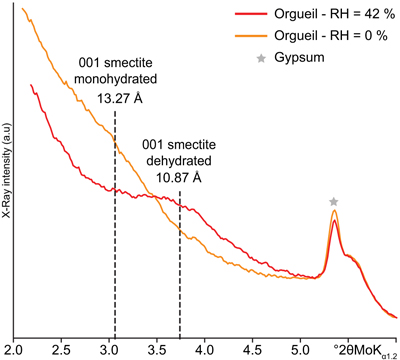

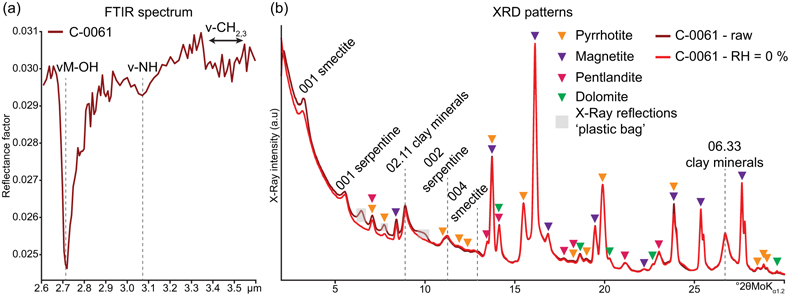

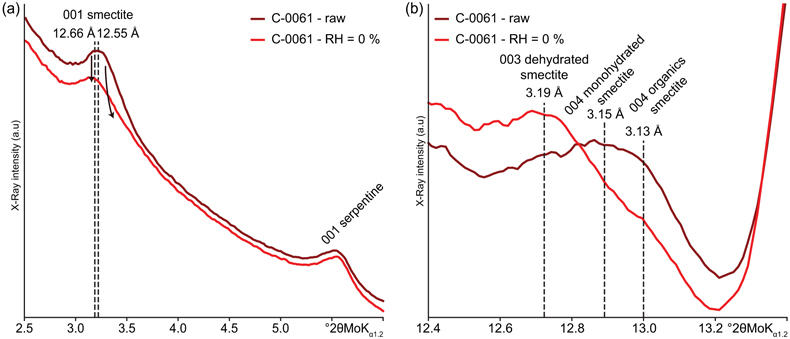

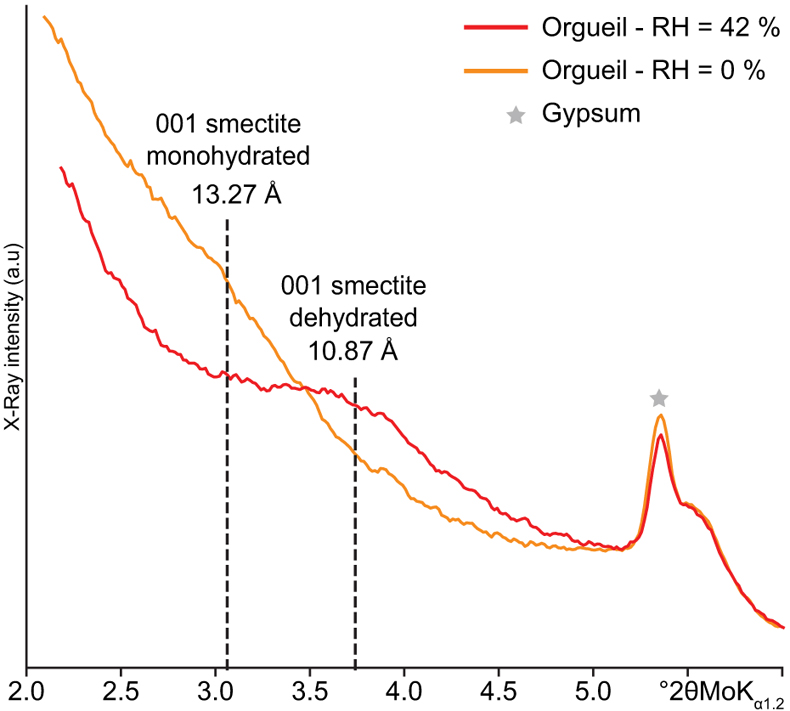

Figure 1 (a) FTIR spectrum of the grain C-0061 acquired within the Curation Facility with the MicrOmega instrument (Pilorget et al., 2022) and obtained from the Astromaterials Science Research Group (ASRG et al., 2022). (b) XRD measurements and the corresponding peak assignation of the grain C-0061 under “raw” and 0 % relative humidity conditions. |  Figure 2 XRD measurements and the corresponding peak assignation of the 00ℓ reflections of the smectite layers of the grain C-0061 under “raw” and 0 % relative humidity (RH) conditions. The arrows indicate the XRD behaviour of the two smectite phases after exposure to 0 % RH. |  Figure 3 XRD measurements and the corresponding peak assignation of the 001 reflection of the smectite layers of Orgueil under “raw” and 0 % relative humidity conditions. |

| Figure 1 | Figure 2 | Figure 3 |

top

Letter

The sample return mission Hayabusa 2 brought back to Earth the most pristine chondritic material to date, from the C-type asteroid Ryugu (Ito et al., 2022

Ito, M., Tomioka, N., Uesugi, M., Yamaguchi, A., Shirai, N., et al. (2022) A pristine record of outer Solar System materials from asteroid Ryugu’s returned sample. Nature Astronomy 6, 1163–1171. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-022-01745-5

; E. Nakamura et al., 2022Nakamura, E., Kobayashi, K., Tanaka, R., Kunihiro, T., Kitagawa, H., et al. (2022) On the origin and evolution of the asteroid Ryugu: A comprehensive geochemical perspective. Proceedings of the Japan Academy, Series B 98, 227–282. https://doi.org/10.2183/pjab.98.015

; T. Nakamura et al., 2022Nakamura, T., Matsumoto, M., Amano, K., Enokido, Y., Zolensky, M.E., et al. (2022) Formation and evolution of carbonaceous asteroid Ryugu: Direct evidence from returned samples. Science 379, eabn8671. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abn8671

). Indeed, unlike meteorites or interplanetary dust particles, the Ryugu grains have never been exposed to terrestrial atmosphere and are kept under N2 in the JAXA Curation Facility at ISAS, Sagamihara. Ryugu grains share numerous features with the chemically primitive but also highly aqueously altered CI group chondrites (E. Nakamura et al., 2022Nakamura, E., Kobayashi, K., Tanaka, R., Kunihiro, T., Kitagawa, H., et al. (2022) On the origin and evolution of the asteroid Ryugu: A comprehensive geochemical perspective. Proceedings of the Japan Academy, Series B 98, 227–282. https://doi.org/10.2183/pjab.98.015

; T. Nakamura et al., 2022Nakamura, T., Matsumoto, M., Amano, K., Enokido, Y., Zolensky, M.E., et al. (2022) Formation and evolution of carbonaceous asteroid Ryugu: Direct evidence from returned samples. Science 379, eabn8671. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abn8671

; Yada et al., 2022Yada, T., Abe, M., Okada, T., Nakato, A., Yogata, K., et al. (2022) Preliminary analysis of the Hayabusa2 samples returned from C-type asteroid Ryugu. Nature Astronomy 6, 214–220. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-021-01550-6

; Yokoyama et al., 2022Yokoyama, T., Nagashima, K., Nakai, I., Young, E.D., Abe, Y., et al. (2022) Samples returned from the asteroid Ryugu are similar to Ivuna-type carbonaceous meteorites. Science 379, eabn7850. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abn7850

), hence offering invaluable insights into the protoplanetary disk and asteroidal alteration processes. They also offer a chance to better characterise the terrestrial alteration that CI meteorites underwent since their fall on Earth (Gounelle and Zolensky, 2001Gounelle, M., Zolensky, M.E. (2001) A terrestrial origin for sulfate veins in CI1 chondrites. Meteoritics & Planetary Science 36, 1321–1329. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1945-5100.2001.tb01827.x

; E. Nakamura et al., 2022Nakamura, E., Kobayashi, K., Tanaka, R., Kunihiro, T., Kitagawa, H., et al. (2022) On the origin and evolution of the asteroid Ryugu: A comprehensive geochemical perspective. Proceedings of the Japan Academy, Series B 98, 227–282. https://doi.org/10.2183/pjab.98.015

; T. Nakamura et al., 2022Nakamura, T., Matsumoto, M., Amano, K., Enokido, Y., Zolensky, M.E., et al. (2022) Formation and evolution of carbonaceous asteroid Ryugu: Direct evidence from returned samples. Science 379, eabn8671. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abn8671

; Yada et al., 2022Yada, T., Abe, M., Okada, T., Nakato, A., Yogata, K., et al. (2022) Preliminary analysis of the Hayabusa2 samples returned from C-type asteroid Ryugu. Nature Astronomy 6, 214–220. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-021-01550-6

; Yokoyama et al., 2022Yokoyama, T., Nagashima, K., Nakai, I., Young, E.D., Abe, Y., et al. (2022) Samples returned from the asteroid Ryugu are similar to Ivuna-type carbonaceous meteorites. Science 379, eabn7850. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abn7850

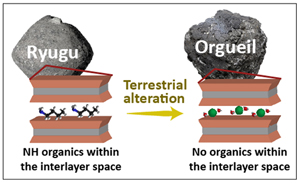

).A puzzling spectroscopic feature of essentially the entire collection of Ryugu grains is the infrared signature of NH-rich compounds as evidenced by the presence of an absorption band at ∼3.06–3.1 μm (Fig. 1a; Pilorget et al., 2022

Pilorget, C., Okada, T., Hamm, V., Brunetto, R., Yada, T., et al. (2022) First compositional analysis of Ryugu samples by the MicrOmega hyperspectral microscope. Nature Astronomy 6, 221–225. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-021-01549-z

; Yada et al., 2022Yada, T., Abe, M., Okada, T., Nakato, A., Yogata, K., et al. (2022) Preliminary analysis of the Hayabusa2 samples returned from C-type asteroid Ryugu. Nature Astronomy 6, 214–220. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-021-01550-6

). This feature is observed by two independent instruments in the Hayabusa 2 Curation Facility, both on bulk samples and on several individual grains. The current interpretation of this feature calls for either NH4+ phyllosilicates, NH4+ hydrated salts and/or nitrogen-rich organics (Pilorget et al., 2022Pilorget, C., Okada, T., Hamm, V., Brunetto, R., Yada, T., et al. (2022) First compositional analysis of Ryugu samples by the MicrOmega hyperspectral microscope. Nature Astronomy 6, 221–225. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-021-01549-z

). However, such an infrared signature has never been observed in any meteorite on Earth, but strikingly similar signatures are reported for Ceres (King et al., 1992King, T.V.V., Clark, R.N., Calvin, W.M., Sherman, D.M., Brown, R.H. (1992) Evidence for Ammonium-Bearing Minerals on Ceres. Science 255, 1551–1553. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.255.5051.1551

; De Sanctis et al., 2015De Sanctis, M.C., Ammannito, E., Raponi, A., Marchi, S., McCord, T.B., et al. (2015) Ammoniated phyllosilicates with a likely outer Solar System origin on (1) Ceres. Nature 528, 241–244. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16172

; Yada et al., 2022Yada, T., Abe, M., Okada, T., Nakato, A., Yogata, K., et al. (2022) Preliminary analysis of the Hayabusa2 samples returned from C-type asteroid Ryugu. Nature Astronomy 6, 214–220. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-021-01550-6

) and a few other asteroids (Takir and Emery, 2012Takir, D., Emery, J.P. (2012) Outer Main Belt asteroids: Identification and distribution of four 3-μm spectral groups. Icarus 219, 641–654. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2012.02.022

).In order to provide an explanation for this puzzling spectroscopic feature of Ryugu, we measured a ∼500 μm-sized sub-part of the grain C-0061 of Ryugu, and grains several hundred μm in size of the Orgueil CI chondrite meteorite (fell in 1864) by X-Ray diffraction (XRD) under different relative humidities. Such XRD experiments allow investigation of the presence of water molecules or organics within the interlayer space of smectite layers (Viennet et al., 2019

Viennet, J.-C., Bernard, S., Le Guillou, C., Jacquemot, P., Balan, E., Delbes, L., Rigaud, B., Georgelin, T., Jaber, M. (2019) Experimental clues for detecting biosignatures on Mars. Geochemical Perspectives Letters 12, 28–33. https://doi.org/10.7185/geochemlet.1931

, 2020Viennet, J.-C., Bernard, S., Le Guillou, C., Jacquemot, P., Delbes, L., Balan, E., Jaber, M. (2020) Influence of the nature of the gas phase on the degradation of RNA during fossilization processes. Applied Clay Science 191, 105616. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clay.2020.105616

, 2022Viennet, J.-C., Le Guillou, C., Remusat, L., Baron, F., Delbes, L., Blanchenet, A.M., Laurent, B., Criouet, I., Bernard, S. (2022) Experimental investigation of Fe-clay/organic interactions under asteroidal conditions. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 318, 352–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2021.12.002

; Lanson et al., 2022Lanson, B., Mignon, P., Velde, M., Bauer, A., Lanson, M., Findling, N., Perez del Valle, C. (2022) Determination of layer charge density in expandable phyllosilicates with alkylammonium ions: A combined experimental and theoretical assessment of the method. Applied Clay Science 229, 106665. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clay.2022.106665

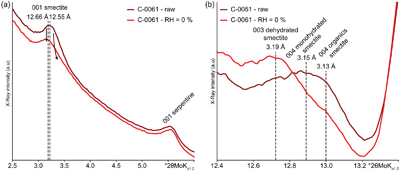

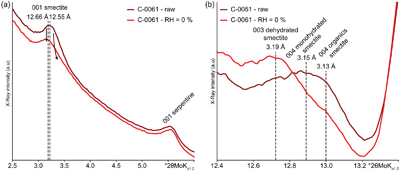

).The mineralogy of grain C-0061 was first determined by XRD measurement prior to any exposure to air. The grain was transferred under nitrogen from the Curation Facility to Tohoku University, and there it was sealed in an airtight plastic container (referred to as “raw”) in a glove box with a low dew point (<−60 °C) and low oxygen pressure (<10 ppm). Like other Ryugu grains, grain C-0061 mainly contains clay minerals, magnetite, pentlandite, pyrrhotite and dolomite (Fig. 1b; E. Nakamura et al., 2022

Nakamura, E., Kobayashi, K., Tanaka, R., Kunihiro, T., Kitagawa, H., et al. (2022) On the origin and evolution of the asteroid Ryugu: A comprehensive geochemical perspective. Proceedings of the Japan Academy, Series B 98, 227–282. https://doi.org/10.2183/pjab.98.015

; T. Nakamura et al., 2022Nakamura, T., Matsumoto, M., Amano, K., Enokido, Y., Zolensky, M.E., et al. (2022) Formation and evolution of carbonaceous asteroid Ryugu: Direct evidence from returned samples. Science 379, eabn8671. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abn8671

), which implies it can be considered a typical Ryugu grain from a mineralogical and petrological point of view. Clay minerals are trioctahedral because of their 02.11 and 06.33 reflections at 4.59 and 1.537 Å, respectively. This is consistent with the Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) feature at 2.7 μm related to metal-OH vibration of trioctahedral clay minerals (Fig. 1a; Pilorget et al., 2022Pilorget, C., Okada, T., Hamm, V., Brunetto, R., Yada, T., et al. (2022) First compositional analysis of Ryugu samples by the MicrOmega hyperspectral microscope. Nature Astronomy 6, 221–225. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-021-01549-z

; Yada et al., 2022Yada, T., Abe, M., Okada, T., Nakato, A., Yogata, K., et al. (2022) Preliminary analysis of the Hayabusa2 samples returned from C-type asteroid Ryugu. Nature Astronomy 6, 214–220. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-021-01550-6

) and with their Mg-rich chemical composition (E. Nakamura et al., 2022Nakamura, E., Kobayashi, K., Tanaka, R., Kunihiro, T., Kitagawa, H., et al. (2022) On the origin and evolution of the asteroid Ryugu: A comprehensive geochemical perspective. Proceedings of the Japan Academy, Series B 98, 227–282. https://doi.org/10.2183/pjab.98.015

; T. Nakamura et al., 2022Nakamura, T., Matsumoto, M., Amano, K., Enokido, Y., Zolensky, M.E., et al. (2022) Formation and evolution of carbonaceous asteroid Ryugu: Direct evidence from returned samples. Science 379, eabn8671. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abn8671

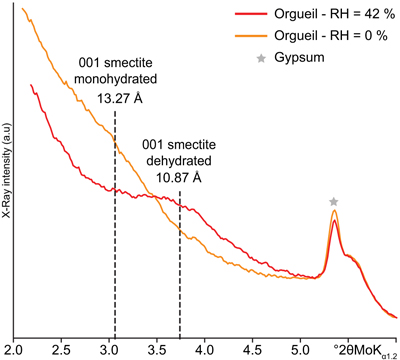

). The XRD peaks at 7.29 and 3.62 Å correspond to the 001 and 002 reflections of serpentine. The positions of the 001 reflection at 12.55 Å (Fig. 2a) and the 004 reflection at 3.15 Å (Fig. 2b) are almost rational, indicating the essentially monohydrated state of the smectite layers (for details please refer to the Supplementary Information; Ferrage, 2016Ferrage, E. (2016) Investigation of the Interlayer Organization of Water and Ions In Smectite from the Combined Use of Diffraction Experiments And Molecular Simulations. A Review of Methodology, Applications, And Perspectives. Clays and Clay Minerals 64, 348–373. https://doi.org/10.1346/CCMN.2016.0640401

). However, based on thermogravimetric analyses coupled with mass spectrometry on representative Ryugu grains (Yokoyama et al., 2022Yokoyama, T., Nagashima, K., Nakai, I., Young, E.D., Abe, Y., et al. (2022) Samples returned from the asteroid Ryugu are similar to Ivuna-type carbonaceous meteorites. Science 379, eabn7850. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abn7850

), the water molecule content within the interlayer space of smectite in the Ryugu samples is low (<0.3 wt. %). Indeed, a monohydrated state for typical saponite would account for ∼2 wt. % of water (Ferrage et al., 2010Ferrage, E., Lanson, B., Michot, L.J., Robert, J.-L. (2010) Hydration Properties and Interlayer Organization of Water and Ions in Synthetic Na-Smectite with Tetrahedral Layer Charge. Part 1. Results from X-ray Diffraction Profile Modeling. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 114, 4515–4526. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp909860p

).

Figure 1 (a) FTIR spectrum of the grain C-0061 acquired within the Curation Facility with the MicrOmega instrument (Pilorget et al., 2022

Pilorget, C., Okada, T., Hamm, V., Brunetto, R., Yada, T., et al. (2022) First compositional analysis of Ryugu samples by the MicrOmega hyperspectral microscope. Nature Astronomy 6, 221–225. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-021-01549-z

) and obtained from the Astromaterials Science Research Group (ASRG et al., 2022Astromaterials Science Research Group (ASRG), Institute of Space and Astronautical Science (ISAS), Institut d’Astrophysique Spatiale (IAS), Yumoto, K., Yabe, Y., Cho, Y., Sugita, S. (2022) Hayabusa2, Ryugu Sample Curatorial Dataset. ISAS/JAXA, Japan. https://doi.org/10.17597/ISAS.DARTS/CUR-Ryugu-description

). (b) XRD measurements and the corresponding peak assignation of the grain C-0061 under “raw” and 0 % relative humidity conditions.

Figure 2 XRD measurements and the corresponding peak assignation of the 00ℓ reflections of the smectite layers of the grain C-0061 under “raw” and 0 % relative humidity (RH) conditions. The arrows indicate the XRD behaviour of the two smectite phases after exposure to 0 % RH.

In order to assess the presence (or absence) of water molecules within the interlayer space, XRD measurements under 0 % of relative humidity (referred as 0 % RH) were carried out (see materials and methods and Fig. S-3 in Supplementary Information for details). The 001 reflection shifts from 12.55 Å under raw conditions to 12.66 Å under 0 % RH (Fig. 2a). Furthermore, the intensity of the XRD peak decreases and a fraction of the intensity shifts toward higher angle (i.e. toward a dehydrated smectite position; see Supplementary Information). The 00ℓ reflections splitting shows that there are, at least, two populations of smectite phases. While there is only one broad peak centred at 3.15 Å under raw conditions, this peak moves partially to 3.19 Å and a shoulder appears at 3.13 Å at 0 % RH (Fig. 2b). The XRD peak at 3.19 Å corresponds to the smectite layers with water molecules desorbing during the process. Such XRD behaviour could be related to the presence of the mixed layering of dehydrated and monohydrated layers (Ferrage et al., 2010

Ferrage, E., Lanson, B., Michot, L.J., Robert, J.-L. (2010) Hydration Properties and Interlayer Organization of Water and Ions in Synthetic Na-Smectite with Tetrahedral Layer Charge. Part 1. Results from X-ray Diffraction Profile Modeling. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 114, 4515–4526. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp909860p

). Hence, such a smectite phase is responsible for the broadening toward higher angles and the intensity drop of the 001 reflection at 12.55 Å under 0 % RH. Nonetheless, the main contribution to the 001 reflection of smectite under 0 % RH is the peak at 12.66 Å. The shoulder centred at 3.13 Å (which does not move at 0 % RH), corresponds to its 004 reflection. The XRD behaviour of these 001 and 004 reflections indicates that water molecules are not present within the interlayer space of these smectite layers of Ryugu.What could be the species accommodated in the interlayer space of smectite layers at ∼12.6 Å? Among clay minerals, the smectite family is a pivotal agent driving organic carbon sequestration/preservation on Earth and asteroids (Blattmann et al., 2019

Blattmann, T.M., Liu, Z., Zhang, Y., Zhao, Y., Haghipour, N., Montluçon, D.B., Plötze, M., Eglinton, T.I. (2019) Mineralogical control on the fate of continentally derived organic matter in the ocean. Science 366, 742–745. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aax5345

). The clay/organic interactions occur either at the edges, or within the interlayer space, of expandable clay minerals. When organic molecules are present within the interlayer space of smectite layers, the layer to layer distance of smectite is modified according to the type of organic molecules and their arrangement (Lagaly et al., 2013Lagaly, G., Ogawa, M., Dékány, I. (2013) Chapter 10.3 - Clay Mineral–Organic Interactions. In: Bergaya, F., Lagaly, G. (Eds.) Developments in Clay Science 5, Handbook of Clay Science. Elsevier, Amsterdam, 435–505. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-098258-8.00015-8

) and the organics lock the interlayer space by preventing water molecules from entering (Lagaly et al., 2013Lagaly, G., Ogawa, M., Dékány, I. (2013) Chapter 10.3 - Clay Mineral–Organic Interactions. In: Bergaya, F., Lagaly, G. (Eds.) Developments in Clay Science 5, Handbook of Clay Science. Elsevier, Amsterdam, 435–505. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-098258-8.00015-8

; Viennet et al., 2019Viennet, J.-C., Bernard, S., Le Guillou, C., Jacquemot, P., Balan, E., Delbes, L., Rigaud, B., Georgelin, T., Jaber, M. (2019) Experimental clues for detecting biosignatures on Mars. Geochemical Perspectives Letters 12, 28–33. https://doi.org/10.7185/geochemlet.1931

, 2020Viennet, J.-C., Bernard, S., Le Guillou, C., Jacquemot, P., Delbes, L., Balan, E., Jaber, M. (2020) Influence of the nature of the gas phase on the degradation of RNA during fossilization processes. Applied Clay Science 191, 105616. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clay.2020.105616

, 2022Viennet, J.-C., Le Guillou, C., Remusat, L., Baron, F., Delbes, L., Blanchenet, A.M., Laurent, B., Criouet, I., Bernard, S. (2022) Experimental investigation of Fe-clay/organic interactions under asteroidal conditions. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 318, 352–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2021.12.002

). Thus, the XRD behaviour observed for the 001 reflection at 12.66 Å of grain C-0061 under 0 % RH is characteristic of the presence of organic matter within the interlayer space. Such a result also explains both the low water molecule content of the interlayer space of Ryugu grains (0.3 wt. %; Yokoyama et al., 2022Yokoyama, T., Nagashima, K., Nakai, I., Young, E.D., Abe, Y., et al. (2022) Samples returned from the asteroid Ryugu are similar to Ivuna-type carbonaceous meteorites. Science 379, eabn7850. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abn7850

) and the lack of a 1.9 μm combination band related to “OH vibrations in H2O molecules” (Pilorget et al., 2022Pilorget, C., Okada, T., Hamm, V., Brunetto, R., Yada, T., et al. (2022) First compositional analysis of Ryugu samples by the MicrOmega hyperspectral microscope. Nature Astronomy 6, 221–225. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-021-01549-z

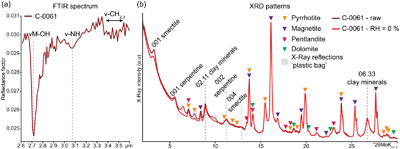

).We also performed the same measurements on the CI meteorite Orgueil. While the results obtained on Ryugu point toward organic molecules fixed within the interlayer space of smectite layers, the XRD measurements on Orgueil show that there are no organic molecules within the interlayer space of smectites. Indeed, the XRD peak at 13.27 Å under 42 % RH, which corresponds mainly to the 001 reflection of monohydrated smectite, shifts toward dehydrated smectite layers after exposure to 0 % RH (Fig. 3). Hence, there are no organics within the interlayer space of the smectite layers of Orgueil.

Figure 3 XRD measurements and the corresponding peak assignation of the 001 reflection of the smectite layers of Orgueil under “raw” and 0 % relative humidity conditions.

Given the strong geochemical, mineralogical and petrological similarities between the Orgueil meteorite and the grains of Ryugu (E. Nakamura et al., 2022

Nakamura, E., Kobayashi, K., Tanaka, R., Kunihiro, T., Kitagawa, H., et al. (2022) On the origin and evolution of the asteroid Ryugu: A comprehensive geochemical perspective. Proceedings of the Japan Academy, Series B 98, 227–282. https://doi.org/10.2183/pjab.98.015

; T. Nakamura et al., 2022Nakamura, T., Matsumoto, M., Amano, K., Enokido, Y., Zolensky, M.E., et al. (2022) Formation and evolution of carbonaceous asteroid Ryugu: Direct evidence from returned samples. Science 379, eabn8671. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abn8671

; Yada et al., 2022Yada, T., Abe, M., Okada, T., Nakato, A., Yogata, K., et al. (2022) Preliminary analysis of the Hayabusa2 samples returned from C-type asteroid Ryugu. Nature Astronomy 6, 214–220. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-021-01550-6

), it appears unlikely that this difference could be explained in terms of asteroidal geochemical processes. On the other hand, Orgueil suffered strong terrestrial alteration. Indeed, abundant sulfates form in Orgueil and in other carbonaceous chondrites by reaction of sulfides with atmospheric water in the meteorite (Gounelle and Zolensky, 2001Gounelle, M., Zolensky, M.E. (2001) A terrestrial origin for sulfate veins in CI1 chondrites. Meteoritics & Planetary Science 36, 1321–1329. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1945-5100.2001.tb01827.x

, 2014Gounelle, M., Zolensky, M.E. (2014) The Orgueil meteorite: 150 years of history. Meteoritics & Planetary Science 49, 1769–1794. https://doi.org/10.1111/maps.12351

; Ito et al., 2022Ito, M., Tomioka, N., Uesugi, M., Yamaguchi, A., Shirai, N., et al. (2022) A pristine record of outer Solar System materials from asteroid Ryugu’s returned sample. Nature Astronomy 6, 1163–1171. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-022-01745-5

; T. Nakamura et al., 2022Nakamura, T., Matsumoto, M., Amano, K., Enokido, Y., Zolensky, M.E., et al. (2022) Formation and evolution of carbonaceous asteroid Ryugu: Direct evidence from returned samples. Science 379, eabn8671. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abn8671

). Furthermore, Mössbauer analysis shows that Ryugu is overall more reduced than Orgueil (T. Nakamura et al., 2022Nakamura, T., Matsumoto, M., Amano, K., Enokido, Y., Zolensky, M.E., et al. (2022) Formation and evolution of carbonaceous asteroid Ryugu: Direct evidence from returned samples. Science 379, eabn8671. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abn8671

). Magnetites from Ryugu are stoichiometric while magnetites from Orgueil are anomalously oxidised (Gunnlaugsson et al., 1994Gunnlaugsson, H.P., Bender Koch, C., Madsen, M.B. (1994) Application of external magnetic field to characterize magnetic oxides in the carbonaceous chondrite Orgueil. Hyperfine Interactions 91, 589–593. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02064575

; T. Nakamura et al., 2022Nakamura, T., Matsumoto, M., Amano, K., Enokido, Y., Zolensky, M.E., et al. (2022) Formation and evolution of carbonaceous asteroid Ryugu: Direct evidence from returned samples. Science 379, eabn8671. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abn8671

). Clay minerals from Ryugu are also more reduced than typical CI and CM carbonaceous chondrites found on Earth so far and ferrihydrite is absent in Ryugu samples (T. Nakamura et al., 2022Nakamura, T., Matsumoto, M., Amano, K., Enokido, Y., Zolensky, M.E., et al. (2022) Formation and evolution of carbonaceous asteroid Ryugu: Direct evidence from returned samples. Science 379, eabn8671. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abn8671

). Degradation of organic molecules could occur via Fe oxidation of clay minerals by the formation of hydroxyl radicals (•OH) which then degrade organics (Chen et al., 2019Chen, N., Fang, G., Liu, G., Zhou, D., Gao, J., Gu, C. (2019) The degradation of diethyl phthalate by reduced smectite clays and dissolved oxygen. Chemical Engineering Journal 355, 247–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2018.08.160

; Huang et al., 2020Huang, L., Liu, Z., Dong, H., Yu, T., Jiang, H., Peng, Y., Shi, L. (2020) Coupling quinoline degradation with Fe redox in clay minerals: A strategy integrating biological and physicochemical processes. Applied Clay Science 188, 105504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clay.2020.105504

; Thomas et al., 2021Thomas, N., Dionysiou, D.D., Pillai, S.C. (2021) Heterogeneous Fenton catalysts: A review of recent advances. Journal of Hazardous Materials 404, 124082. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124082

). Moreover, the oxidation of structural Fe in smectite decreases its permanent charge, which in turn decreases the capacity of smectite to adsorb positively charged molecules within their interlayer space. This strongly suggests that the terrestrial alteration of most primitive extraterrestrial samples is even more pervasive than previously suggested. Indeed, in addition to Fe-bearing minerals, organics of carbonaceous chondritic materials can also be modified due to terrestrial oxidation, explaining in part the differences in alkali-bearing organic molecules between Ryugu and Orgueil (E. Nakamura et al., 2022Nakamura, E., Kobayashi, K., Tanaka, R., Kunihiro, T., Kitagawa, H., et al. (2022) On the origin and evolution of the asteroid Ryugu: A comprehensive geochemical perspective. Proceedings of the Japan Academy, Series B 98, 227–282. https://doi.org/10.2183/pjab.98.015

). Note that, recently, XRD revealed variability of the smectite structure in some Ryugu grains (T. Nakamura et al., 2022Nakamura, T., Matsumoto, M., Amano, K., Enokido, Y., Zolensky, M.E., et al. (2022) Formation and evolution of carbonaceous asteroid Ryugu: Direct evidence from returned samples. Science 379, eabn8671. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abn8671

). Since this variability may point to a diversity of interlayer species, it would be necessary, in the near future, to determine the exact fraction of Ryugu’s smectites containing organics within the interlayer space.The presence of organics within the interlayer space of smectite could help better understand the origins of organics within CI objects. For instance, it has been proposed that the hydrothermal alteration of soluble organics within asteroids could be the origin of insoluble organic matter (IOM) (Cody et al., 2011

Cody, G.D., Gupta, N.S., Briggs, D.E.G., Kilcoyne, A.L.D., Summons, R.E., Kenig, F., Plotnick, R.E., Scott, A.C. (2011) Molecular signature of chitin-protein complex in Paleozoic arthropods. Geology 39, 255–258. https://doi.org/10.1130/G31648.1

). Yet, in presence of smectite, the formation of IOM is inhibited by the fixation of a part of the organic molecules in solution within the interlayer space of smectite, preventing the necessary reaction of polymerisation and condensation steps for the formation of IOM (Viennet et al., 2022Viennet, J.-C., Le Guillou, C., Remusat, L., Baron, F., Delbes, L., Blanchenet, A.M., Laurent, B., Criouet, I., Bernard, S. (2022) Experimental investigation of Fe-clay/organic interactions under asteroidal conditions. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 318, 352–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2021.12.002

). Here, due to the presence of organic molecules within the interlayer space, we infer that potentially less IOM was formed during the asteroidal alteration of the parent body of Ryugu and more soluble organic matter was locked down within the interlayer space of smectite layers. Such observations would also argue for origins of IOM prior to parent body processing (Alexander et al., 2007Alexander, C.M.O’D., Fogel, M., Yabuta, H., Cody, G.D. (2007) The origin and evolution of chondrites recorded in the elemental and isotopic compositions of their macromolecular organic matter. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 71, 4380–4403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2007.06.052

; E. Nakamura et al., 2022Nakamura, E., Kobayashi, K., Tanaka, R., Kunihiro, T., Kitagawa, H., et al. (2022) On the origin and evolution of the asteroid Ryugu: A comprehensive geochemical perspective. Proceedings of the Japan Academy, Series B 98, 227–282. https://doi.org/10.2183/pjab.98.015

).NH4+ phyllosilicates, NH4+ hydrated salts and/or nitrogen-rich organics are the likely candidates to explain the infrared NH signature of Ryugu (Pilorget et al., 2022

Pilorget, C., Okada, T., Hamm, V., Brunetto, R., Yada, T., et al. (2022) First compositional analysis of Ryugu samples by the MicrOmega hyperspectral microscope. Nature Astronomy 6, 221–225. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-021-01549-z

). Yet, ammonium-bearing smectites allow the absorption of water molecules within their interlayer space which will give a XRD behaviour similar to the reference smectite considered here (Supplementary Information Fig. S-3) and a collapsed interlayer space at ∼10 Å under 0 % RH (Gautier et al., 2010Gautier, M., Muller, F., Le Forestier, L., Beny, J.-M., Guegan, R. (2010) NH4-smectite: Characterization, hydration properties and hydro mechanical behaviour. Applied Clay Science 49, 247–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clay.2010.05.013

; Viennet et al., 2019Viennet, J.-C., Bernard, S., Le Guillou, C., Jacquemot, P., Balan, E., Delbes, L., Rigaud, B., Georgelin, T., Jaber, M. (2019) Experimental clues for detecting biosignatures on Mars. Geochemical Perspectives Letters 12, 28–33. https://doi.org/10.7185/geochemlet.1931

). In addition, the experimental ammoniation of the Orgueil meteorite produced weak absorptions between 3.0 and 3.1 μm while the XRD data demonstrated the NH4+ adsorption within the interlayer space of smectite (Ehlmann et al., 2018Ehlmann, B.L., Hodyss, R., Bristow, T.F., Rossman, G.R., Ammannito, E., De Sanctis, M.C., Raymond, C.A. (2018) Ambient and cold‐temperature infrared spectra and XRD patterns of ammoniated phyllosilicates and carbonaceous chondrite meteorites relevant to Ceres and other solar system bodies. Meteoritics & Planetary Science 53, 1884–1901. https://doi.org/10.1111/maps.13103

). Yet, it remains unclear if the attempt at producing the 3.06–3.1 μm infrared feature could be related to particular Orgueil smectite properties or NH4+ complexing with organics or other constituents (Ehlmann et al., 2018Ehlmann, B.L., Hodyss, R., Bristow, T.F., Rossman, G.R., Ammannito, E., De Sanctis, M.C., Raymond, C.A. (2018) Ambient and cold‐temperature infrared spectra and XRD patterns of ammoniated phyllosilicates and carbonaceous chondrite meteorites relevant to Ceres and other solar system bodies. Meteoritics & Planetary Science 53, 1884–1901. https://doi.org/10.1111/maps.13103

). Furthermore, NH4+ hydrated salts have not been observed so far in Ryugu and are not present in grain C-0061 based on XRD data (Fig. 1b). Instead, the fixation of NH-rich organic compounds in the interlayer space can explain the position of the NH stretching vibration in Ryugu (Fig. 1a), which is shifted to higher wavelengths when organics interact with NH4+ within the interlayer space (Gautier et al., 2017Gautier, M., Muller, F., Le Forestier, L. (2017) Interactions of ammonium-smectite with volatile organic compounds from leachates. Clay Minerals 52, 143–159. https://doi.org/10.1180/claymin.2017.052.1.10

) or is due to the presence of NH3+ groups (Liu et al., 2013Liu, H., Yuan, P., Qin, Z., Liu, D., Tan, D., Zhu, J., He, H. (2013) Thermal degradation of organic matter in the interlayer clay–organic complex: A TG-FTIR study on a montmorillonite/12-aminolauric acid system. Applied Clay Science 80–81, 398–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clay.2013.07.005

). In addition, the fixation of NH organics within the interlayer space of smectite could offer an alternative hypothesis to the difficulty of producing a clear 3.06–3.1 μm feature by ammoniation of the Orgueil CI meteorite (Ehlmann et al., 2018Ehlmann, B.L., Hodyss, R., Bristow, T.F., Rossman, G.R., Ammannito, E., De Sanctis, M.C., Raymond, C.A. (2018) Ambient and cold‐temperature infrared spectra and XRD patterns of ammoniated phyllosilicates and carbonaceous chondrite meteorites relevant to Ceres and other solar system bodies. Meteoritics & Planetary Science 53, 1884–1901. https://doi.org/10.1111/maps.13103

). We therefore postulate that the XRD behaviour observed here is related to a nitrogen-rich organic matter trapped within the interlayer space of Ryugu smectites. The exact nature of the interactions between the smectite layers and organics remains difficult to determine. Yet when positively charged, NH organics can compensate the permanent charge of smectite (Lagaly et al., 2013Lagaly, G., Ogawa, M., Dékány, I. (2013) Chapter 10.3 - Clay Mineral–Organic Interactions. In: Bergaya, F., Lagaly, G. (Eds.) Developments in Clay Science 5, Handbook of Clay Science. Elsevier, Amsterdam, 435–505. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-098258-8.00015-8

; Viennet et al., 2019Viennet, J.-C., Bernard, S., Le Guillou, C., Jacquemot, P., Balan, E., Delbes, L., Rigaud, B., Georgelin, T., Jaber, M. (2019) Experimental clues for detecting biosignatures on Mars. Geochemical Perspectives Letters 12, 28–33. https://doi.org/10.7185/geochemlet.1931

, 2020Viennet, J.-C., Bernard, S., Le Guillou, C., Jacquemot, P., Delbes, L., Balan, E., Jaber, M. (2020) Influence of the nature of the gas phase on the degradation of RNA during fossilization processes. Applied Clay Science 191, 105616. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clay.2020.105616

, 2022Viennet, J.-C., Le Guillou, C., Remusat, L., Baron, F., Delbes, L., Blanchenet, A.M., Laurent, B., Criouet, I., Bernard, S. (2022) Experimental investigation of Fe-clay/organic interactions under asteroidal conditions. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 318, 352–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2021.12.002

). N heterocyclic compounds, which can form positively charged ions, were found in Ryugu (E. Nakamura et al., 2022Nakamura, E., Kobayashi, K., Tanaka, R., Kunihiro, T., Kitagawa, H., et al. (2022) On the origin and evolution of the asteroid Ryugu: A comprehensive geochemical perspective. Proceedings of the Japan Academy, Series B 98, 227–282. https://doi.org/10.2183/pjab.98.015

) and N-bearing organic compounds were detected in a fluid inclusion in a Ryugu pyrrhotite crystal (T. Nakamura et al., 2022Nakamura, T., Matsumoto, M., Amano, K., Enokido, Y., Zolensky, M.E., et al. (2022) Formation and evolution of carbonaceous asteroid Ryugu: Direct evidence from returned samples. Science 379, eabn8671. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abn8671

). Note that, similar d-spacing can be obtained for different types of organic molecules and smectite structures (Lanson et al., 2022Lanson, B., Mignon, P., Velde, M., Bauer, A., Lanson, M., Findling, N., Perez del Valle, C. (2022) Determination of layer charge density in expandable phyllosilicates with alkylammonium ions: A combined experimental and theoretical assessment of the method. Applied Clay Science 229, 106665. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clay.2022.106665

), which does not allow us to investigate further the nature of organics within the interlayer space of Ryugu’s smectite. Achieving a better understanding of the link between the nature of NH organics and smectite structure related to FTIR and XRD behaviours will require many additional experimental studies. By extension, we propose that the reflectance spectra of Ceres may be interpreted as a signature of NH-rich organics within the interlayer space of phyllosilicates instead of NH4+ (King et al., 1992King, T.V.V., Clark, R.N., Calvin, W.M., Sherman, D.M., Brown, R.H. (1992) Evidence for Ammonium-Bearing Minerals on Ceres. Science 255, 1551–1553. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.255.5051.1551

; De Sanctis et al., 2015De Sanctis, M.C., Ammannito, E., Raponi, A., Marchi, S., McCord, T.B., et al. (2015) Ammoniated phyllosilicates with a likely outer Solar System origin on (1) Ceres. Nature 528, 241–244. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16172

; Yada et al., 2022Yada, T., Abe, M., Okada, T., Nakato, A., Yogata, K., et al. (2022) Preliminary analysis of the Hayabusa2 samples returned from C-type asteroid Ryugu. Nature Astronomy 6, 214–220. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-021-01550-6

). Given the ability of smectite layers to adsorb, concentrate, protect and serve as polymerisation templates for organic molecules, they might play a key role for prebiotic reactions which are necessary steps in the origin of life (Bernal, 1951Bernal, J.D. (1951) The Physical Basis of Life. Routledge and Kegan Paul, London.

; Viennet et al., 2021Viennet, J.-C., Bernard, S., Le Guillou, C., Sautter, V., Grégoire, B., et al. (2021) Martian Magmatic Clay Minerals Forming Vesicles: Perfect Niches for Emerging Life? Astrobiology 21, 605–612. https://doi.org/10.1089/ast.2020.2345

), further increasing the astrobiological potential of the dwarf planet Ceres. More IR experimental work on NH-bearing organics and their adsorption within the interlayer space of smectite and comparison to Ceres reflectance spectra would allow a more comprehensive view of the nature of the NH stretching vibrations of Ceres.Altogether, the results of the present study show that the nitrogen-rich infrared signature in Ryugu could be attributed to NH-bearing organic molecules trapped within the interlayer space of smectite layers in Ryugu. This signature is no longer observed in the Orgueil CI meteorite and perhaps other CI meteorites, most likely because of terrestrial oxidation leading to the oxidation and the desorption of organic molecules within their interlayer space.

top

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge L. Delbes from the X-ray diffraction facilities at IMPMC. Special thanks go to Hicham Moutaabbid for his help during the sample preparation with the Ar-Glove box operating at IMPMC and to I. Criouet for providing the synthetic smectite. The authors thanks the meteorite collection of the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle for providing the grains of the Orgueil meteorite (Inventory number 234). We gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Paris Ile-de-France Region DIM ACAV+ funding (PARYUGU), from the ATM 2022_project “Orgueil” (OE-7590) from the Muséum Nationale d’Histoire Naturelle, in France, from the CNES (MIN-PET Hayabusa2), and from Financial support provided by The H2020 European Research Council (ERC) (SOLARYS ERC-CoG2017_771691). This work has been funded by the Centre National d’Etudes Spatiales (CNES- France) and by the ANR project CLASSY (Grant ANR-17- CE31-0004-02) of the French Agence Nationale de la Recherche. This research used resources of the FACCTS programme, and funding from the U.S. DOE Office of Science-Basic Energy Sciences, under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. Finally, this manuscript has benefited from constructive comments by Mike Zolensky and two anonymous reviewers, as well as from associate editor Francis McCubbin.

Editor: Francis McCubbin

top

References

Alexander, C.M.O’D., Fogel, M., Yabuta, H., Cody, G.D. (2007) The origin and evolution of chondrites recorded in the elemental and isotopic compositions of their macromolecular organic matter. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 71, 4380–4403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2007.06.052

Show in context

Show in context Such observations would also argue for origins of IOM prior to parent body processing (Alexander et al., 2007; E. Nakamura et al., 2022).

View in article

Astromaterials Science Research Group (ASRG), Institute of Space and Astronautical Science (ISAS), Institut d’Astrophysique Spatiale (IAS), Yumoto, K., Yabe, Y., Cho, Y., Sugita, S. (2022) Hayabusa2, Ryugu Sample Curatorial Dataset. ISAS/JAXA, Japan. https://doi.org/10.17597/ISAS.DARTS/CUR-Ryugu-description

Show in context

Show in context (a) FTIR spectrum of the grain C-0061 acquired within the Curation Facility with the MicrOmega instrument (Pilorget et al., 2022) and obtained from the Astromaterials Science Research Group (ASRG et al., 2022).

View in article

Bernal, J.D. (1951) The Physical Basis of Life. Routledge and Kegan Paul, London.

Show in context

Show in context Given the ability of smectite layers to adsorb, concentrate, protect and serve as polymerisation templates for organic molecules, they might play a key role for prebiotic reactions which are necessary steps in the origin of life (Bernal, 1951; Viennet et al., 2021), further increasing the astrobiological potential of the dwarf planet Ceres.

View in article

Blattmann, T.M., Liu, Z., Zhang, Y., Zhao, Y., Haghipour, N., Montluçon, D.B., Plötze, M., Eglinton, T.I. (2019) Mineralogical control on the fate of continentally derived organic matter in the ocean. Science 366, 742–745. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aax5345

Show in context

Show in context What could be the species accommodated in the interlayer space of smectite layers at ∼12.6 Å? Among clay minerals, the smectite family is a pivotal agent driving organic carbon sequestration/preservation on Earth and asteroids (Blattmann et al., 2019).

View in article

Chen, N., Fang, G., Liu, G., Zhou, D., Gao, J., Gu, C. (2019) The degradation of diethyl phthalate by reduced smectite clays and dissolved oxygen. Chemical Engineering Journal 355, 247–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2018.08.160

Show in context

Show in context Degradation of organic molecules could occur via Fe oxidation of clay minerals by the formation of hydroxyl radicals (•OH) which then degrade organics (Chen et al., 2019; Huang et al., 2020; Thomas et al., 2021).

View in article

Cody, G.D., Gupta, N.S., Briggs, D.E.G., Kilcoyne, A.L.D., Summons, R.E., Kenig, F., Plotnick, R.E., Scott, A.C. (2011) Molecular signature of chitin-protein complex in Paleozoic arthropods. Geology 39, 255–258. https://doi.org/10.1130/G31648.1

Show in context

Show in context For instance, it has been proposed that the hydrothermal alteration of soluble organics within asteroids could be the origin of insoluble organic matter (IOM) (Cody et al., 2011).

View in article

De Sanctis, M.C., Ammannito, E., Raponi, A., Marchi, S., McCord, T.B., et al. (2015) Ammoniated phyllosilicates with a likely outer Solar System origin on (1) Ceres. Nature 528, 241–244. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16172

Show in context

Show in context However, such an infrared signature has never been observed in any meteorite on Earth, but strikingly similar signatures are reported for Ceres (King et al., 1992; De Sanctis et al., 2015; Yada et al., 2022) and a few other asteroids (Takir and Emery, 2012).

View in article

By extension, we propose that the reflectance spectra of Ceres may be interpreted as a signature of NH-rich organics within the interlayer space of phyllosilicates instead of NH4+ (King et al., 1992; De Sanctis et al., 2015; Yada et al., 2022).

View in article

Ehlmann, B.L., Hodyss, R., Bristow, T.F., Rossman, G.R., Ammannito, E., De Sanctis, M.C., Raymond, C.A. (2018) Ambient and cold‐temperature infrared spectra and XRD patterns of ammoniated phyllosilicates and carbonaceous chondrite meteorites relevant to Ceres and other solar system bodies. Meteoritics & Planetary Science 53, 1884–1901. https://doi.org/10.1111/maps.13103

Show in context

Show in context In addition, the experimental ammoniation of the Orgueil meteorite produced weak absorptions between 3.0 and 3.1 μm while the XRD data demonstrated the NH4+ adsorption within the interlayer space of smectite (Ehlmann et al., 2018).

View in article

Yet, it remains unclear if the attempt at producing the 3.06–3.1 μm infrared feature could be related to particular Orgueil smectite properties or NH4+ complexing with organics or other constituents (Ehlmann et al., 2018).

View in article

In addition, the fixation of NH organics within the interlayer space of smectite could offer an alternative hypothesis to the difficulty of producing a clear 3.06–3.1 μm feature by ammoniation of the Orgueil CI meteorite (Ehlmann et al., 2018).

View in article

Ferrage, E. (2016) Investigation of the Interlayer Organization of Water and Ions In Smectite from the Combined Use of Diffraction Experiments And Molecular Simulations. A Review of Methodology, Applications, And Perspectives. Clays and Clay Minerals 64, 348–373. https://doi.org/10.1346/CCMN.2016.0640401

Show in context

Show in context The XRD peaks at 7.29 and 3.62 Å correspond to the 001 and 002 reflections of serpentine. The positions of the 001 reflection at 12.55 Å (Fig. 2a) and the 004 reflection at 3.15 Å (Fig. 2b) are almost rational, indicating the essentially monohydrated state of the smectite layers (for details please refer to the Supplementary Information; Ferrage, 2016).

View in article

Ferrage, E., Lanson, B., Michot, L.J., Robert, J.-L. (2010) Hydration Properties and Interlayer Organization of Water and Ions in Synthetic Na-Smectite with Tetrahedral Layer Charge. Part 1. Results from X-ray Diffraction Profile Modeling. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 114, 4515–4526. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp909860p

Show in context

Show in context Indeed, a monohydrated state for typical saponite would account for ∼2 wt. % of water (Ferrage et al., 2010).

View in article

Such XRD behaviour could be related to the presence of the mixed layering of dehydrated and monohydrated layers (Ferrage et al., 2010).

View in article

Gautier, M., Muller, F., Le Forestier, L., Beny, J.-M., Guegan, R. (2010) NH4-smectite: Characterization, hydration properties and hydro mechanical behaviour. Applied Clay Science 49, 247–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clay.2010.05.013

Show in context

Show in context Yet, ammonium-bearing smectites allow the absorption of water molecules within their interlayer space which will give a XRD behaviour similar to the reference smectite considered here (Supplementary Information Fig. S-3) and a collapsed interlayer space at ∼10 Å under 0 % RH (Gautier et al., 2010; Viennet et al., 2019).

View in article

Gautier, M., Muller, F., Le Forestier, L. (2017) Interactions of ammonium-smectite with volatile organic compounds from leachates. Clay Minerals 52, 143–159. https://doi.org/10.1180/claymin.2017.052.1.10

Show in context

Show in context Instead, the fixation of NH-rich organic compounds in the interlayer space can explain the position of the NH stretching vibration in Ryugu (Fig. 1a), which is shifted to higher wavelengths when organics interact with NH4+ within the interlayer space (Gautier et al., 2017) or is due to the presence of NH3+ groups (Liu et al., 2013).

View in article

Gounelle, M., Zolensky, M.E. (2001) A terrestrial origin for sulfate veins in CI1 chondrites. Meteoritics & Planetary Science 36, 1321–1329. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1945-5100.2001.tb01827.x

Show in context

Show in context They also offer a chance to better characterise the terrestrial alteration that CI meteorites underwent since their fall on Earth (Gounelle and Zolensky, 2001; E. Nakamura et al., 2022; T. Nakamura et al., 2022; Yada et al., 2022; Yokoyama et al., 2022).

View in article

Indeed, abundant sulfates form in Orgueil and in other carbonaceous chondrites by reaction of sulfides with atmospheric water in the meteorite (Gounelle and Zolensky, 2001, 2014; Ito et al., 2022; T. Nakamura et al., 2022).

View in article

Gounelle, M., Zolensky, M.E. (2014) The Orgueil meteorite: 150 years of history. Meteoritics & Planetary Science 49, 1769–1794. https://doi.org/10.1111/maps.12351

Show in context

Show in context Indeed, abundant sulfates form in Orgueil and in other carbonaceous chondrites by reaction of sulfides with atmospheric water in the meteorite (Gounelle and Zolensky, 2001, 2014; Ito et al., 2022; T. Nakamura et al., 2022).

View in article

Gunnlaugsson, H.P., Bender Koch, C., Madsen, M.B. (1994) Application of external magnetic field to characterize magnetic oxides in the carbonaceous chondrite Orgueil. Hyperfine Interactions 91, 589–593. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02064575

Show in context

Show in context Magnetites from Ryugu are stoichiometric while magnetites from Orgueil are anomalously oxidised (Gunnlaugsson et al., 1994; T. Nakamura et al., 2022).

View in article

Huang, L., Liu, Z., Dong, H., Yu, T., Jiang, H., Peng, Y., Shi, L. (2020) Coupling quinoline degradation with Fe redox in clay minerals: A strategy integrating biological and physicochemical processes. Applied Clay Science 188, 105504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clay.2020.105504

Show in context

Show in context Degradation of organic molecules could occur via Fe oxidation of clay minerals by the formation of hydroxyl radicals (•OH) which then degrade organics (Chen et al., 2019; Huang et al., 2020; Thomas et al., 2021).

View in article

Ito, M., Tomioka, N., Uesugi, M., Yamaguchi, A., Shirai, N., et al. (2022) A pristine record of outer Solar System materials from asteroid Ryugu’s returned sample. Nature Astronomy 6, 1163–1171. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-022-01745-5

Show in context

Show in context The sample return mission Hayabusa 2 brought back to Earth the most pristine chondritic material to date, from the C-type asteroid Ryugu (Ito et al., 2022; E. Nakamura et al., 2022; T. Nakamura et al., 2022).

View in article

Indeed, abundant sulfates form in Orgueil and in other carbonaceous chondrites by reaction of sulfides with atmospheric water in the meteorite (Gounelle and Zolensky, 2001, 2014; Ito et al., 2022; T. Nakamura et al., 2022).

View in article

King, T.V.V., Clark, R.N., Calvin, W.M., Sherman, D.M., Brown, R.H. (1992) Evidence for Ammonium-Bearing Minerals on Ceres. Science 255, 1551–1553. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.255.5051.1551

Show in context

Show in context However, such an infrared signature has never been observed in any meteorite on Earth, but strikingly similar signatures are reported for Ceres (King et al., 1992; De Sanctis et al., 2015; Yada et al., 2022) and a few other asteroids (Takir and Emery, 2012).

View in article

By extension, we propose that the reflectance spectra of Ceres may be interpreted as a signature of NH-rich organics within the interlayer space of phyllosilicates instead of NH4+ (King et al., 1992; De Sanctis et al., 2015; Yada et al., 2022).

View in article

Lagaly, G., Ogawa, M., Dékány, I. (2013) Chapter 10.3 - Clay Mineral–Organic Interactions. In: Bergaya, F., Lagaly, G. (Eds.) Developments in Clay Science 5, Handbook of Clay Science. Elsevier, Amsterdam, 435–505. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-098258-8.00015-8

Show in context

Show in context When organic molecules are present within the interlayer space of smectite layers, the layer to layer distance of smectite is modified according to the type of organic molecules and their arrangement (Lagaly et al., 2013) and the organics lock the interlayer space by preventing water molecules from entering (Lagaly et al., 2013; Viennet et al., 2019, 2020, 2022).

View in article

Yet when positively charged, NH organics can compensate the permanent charge of smectite (Lagaly et al., 2013; Viennet et al., 2019, 2020, 2022).

View in article

Lanson, B., Mignon, P., Velde, M., Bauer, A., Lanson, M., Findling, N., Perez del Valle, C. (2022) Determination of layer charge density in expandable phyllosilicates with alkylammonium ions: A combined experimental and theoretical assessment of the method. Applied Clay Science 229, 106665. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clay.2022.106665

Show in context

Show in context Such XRD experiments allow investigation of the presence of water molecules or organics within the interlayer space of smectite layers (Viennet et al., 2019, 2020, 2022; Lanson et al., 2022).

View in article

Note that, similar d-spacing can be obtained for different types of organic molecules and smectite structures (Lanson et al., 2022), which does not allow us to investigate further the nature of organics within the interlayer space of Ryugu’s smectite.

View in article

Liu, H., Yuan, P., Qin, Z., Liu, D., Tan, D., Zhu, J., He, H. (2013) Thermal degradation of organic matter in the interlayer clay–organic complex: A TG-FTIR study on a montmorillonite/12-aminolauric acid system. Applied Clay Science 80–81, 398–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clay.2013.07.005

Show in context

Show in context Instead, the fixation of NH-rich organic compounds in the interlayer space can explain the position of the NH stretching vibration in Ryugu (Fig. 1a), which is shifted to higher wavelengths when organics interact with NH4+ within the interlayer space (Gautier et al., 2017) or is due to the presence of NH3+ groups (Liu et al., 2013).

View in article

Nakamura, E., Kobayashi, K., Tanaka, R., Kunihiro, T., Kitagawa, H., et al. (2022) On the origin and evolution of the asteroid Ryugu: A comprehensive geochemical perspective. Proceedings of the Japan Academy, Series B 98, 227–282. https://doi.org/10.2183/pjab.98.015

Show in context

Show in context The sample return mission Hayabusa 2 brought back to Earth the most pristine chondritic material to date, from the C-type asteroid Ryugu (Ito et al., 2022; E. Nakamura et al., 2022; T. Nakamura et al., 2022).

View in article

Ryugu grains share numerous features with the chemically primitive but also highly aqueously altered CI group chondrites (E. Nakamura et al., 2022; T. Nakamura et al., 2022; Yada et al., 2022; Yokoyama et al., 2022), hence offering invaluable insights into the protoplanetary disk and asteroidal alteration processes.

View in article

They also offer a chance to better characterise the terrestrial alteration that CI meteorites underwent since their fall on Earth (Gounelle and Zolensky, 2001; E. Nakamura et al., 2022; T. Nakamura et al., 2022; Yada et al., 2022; Yokoyama et al., 2022).

View in article

Like other Ryugu grains, grain C-0061 mainly contains clay minerals, magnetite, pentlandite, pyrrhotite and dolomite (Fig. 1b; E. Nakamura et al., 2022; T. Nakamura et al., 2022), which implies it can be considered a typical Ryugu grain from a mineralogical and petrological point of view.

View in article

Given the strong geochemical, mineralogical and petrological similarities between the Orgueil meteorite and the grains of Ryugu (E. Nakamura et al., 2022; T. Nakamura et al., 2022; Yada et al., 2022), it appears unlikely that this difference could be explained in terms of asteroidal geochemical processes.

View in article This is consistent with the Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) feature at 2.7 μm related to metal-OH vibration of trioctahedral clay minerals (Fig. 1a; Pilorget et al., 2022; Yada et al., 2022) and with their Mg-rich chemical composition (E. Nakamura et al., 2022; T. Nakamura et al., 2022).

View in article

Indeed, in addition to Fe-bearing minerals, organics of carbonaceous chondritic materials can also be modified due to terrestrial oxidation, explaining in part the differences in alkali-bearing organic molecules between Ryugu and Orgueil (E. Nakamura et al., 2022).

View in article

Such observations would also argue for origins of IOM prior to parent body processing (Alexander et al., 2007; E. Nakamura et al., 2022).

View in article

N heterocyclic compounds, which can form positively charged ions, were found in Ryugu (E. Nakamura et al., 2022) and N-bearing organic compounds were detected in a fluid inclusion in a Ryugu pyrrhotite crystal (T. Nakamura et al., 2022).

View in article

Nakamura, T., Matsumoto, M., Amano, K., Enokido, Y., Zolensky, M.E., et al. (2022) Formation and evolution of carbonaceous asteroid Ryugu: Direct evidence from returned samples. Science 379, eabn8671. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abn8671

Show in context

Show in context The sample return mission Hayabusa 2 brought back to Earth the most pristine chondritic material to date, from the C-type asteroid Ryugu (Ito et al., 2022; E. Nakamura et al., 2022; T. Nakamura et al., 2022).

View in article

Ryugu grains share numerous features with the chemically primitive but also highly aqueously altered CI group chondrites (E. Nakamura et al., 2022; T. Nakamura et al., 2022; Yada et al., 2022; Yokoyama et al., 2022), hence offering invaluable insights into the protoplanetary disk and asteroidal alteration processes.

View in article

They also offer a chance to better characterise the terrestrial alteration that CI meteorites underwent since their fall on Earth (Gounelle and Zolensky, 2001; E. Nakamura et al., 2022; T. Nakamura et al., 2022; Yada et al., 2022; Yokoyama et al., 2022).

View in article

Like other Ryugu grains, grain C-0061 mainly contains clay minerals, magnetite, pentlandite, pyrrhotite and dolomite (Fig. 1b; E. Nakamura et al., 2022; T. Nakamura et al., 2022), which implies it can be considered a typical Ryugu grain from a mineralogical and petrological point of view.

View in article

This is consistent with the Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) feature at 2.7 μm related to metal-OH vibration of trioctahedral clay minerals (Fig. 1a; Pilorget et al., 2022; Yada et al., 2022) and with their Mg-rich chemical composition (E. Nakamura et al., 2022; T. Nakamura et al., 2022).

View in article

Given the strong geochemical, mineralogical and petrological similarities between the Orgueil meteorite and the grains of Ryugu (E. Nakamura et al., 2022; T. Nakamura et al., 2022; Yada et al., 2022), it appears unlikely that this difference could be explained in terms of asteroidal geochemical processes.

View in article

Indeed, abundant sulfates form in Orgueil and in other carbonaceous chondrites by reaction of sulfides with atmospheric water in the meteorite (Gounelle and Zolensky, 2001, 2014; Ito et al., 2022; T. Nakamura et al., 2022).

View in article

Furthermore, Mössbauer analysis shows that Ryugu is overall more reduced than Orgueil (T. Nakamura et al., 2022).

View in article

Magnetites from Ryugu are stoichiometric while magnetites from Orgueil are anomalously oxidised (Gunnlaugsson et al., 1994; T. Nakamura et al., 2022).

View in article

Clay minerals from Ryugu are also more reduced than typical CI and CM carbonaceous chondrites found on Earth so far and ferrihydrite is absent in Ryugu samples (T. Nakamura et al., 2022).

View in article

Note that, recently, XRD revealed variability of the smectite structure in some Ryugu grains (T. Nakamura et al., 2022).

View in article

N heterocyclic compounds, which can form positively charged ions, were found in Ryugu (E. Nakamura et al., 2022) and N-bearing organic compounds were detected in a fluid inclusion in a Ryugu pyrrhotite crystal (T. Nakamura et al., 2022).

View in article

Pilorget, C., Okada, T., Hamm, V., Brunetto, R., Yada, T., et al. (2022) First compositional analysis of Ryugu samples by the MicrOmega hyperspectral microscope. Nature Astronomy 6, 221–225. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-021-01549-z

Show in context

Show in context A puzzling spectroscopic feature of essentially the entire collection of Ryugu grains is the infrared signature of NH-rich compounds as evidenced by the presence of an absorption band at ∼3.06–3.1 μm (Fig. 1a; Pilorget et al., 2022; Yada et al., 2022).

View in article

The current interpretation of this feature calls for either NH4+ phyllosilicates, NH4+ hydrated salts and/or nitrogen-rich organics (Pilorget et al., 2022).

View in article

This is consistent with the Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) feature at 2.7 μm related to metal-OH vibration of trioctahedral clay minerals (Fig. 1a; Pilorget et al., 2022; Yada et al., 2022) and with their Mg-rich chemical composition (E. Nakamura et al., 2022; T. Nakamura et al., 2022).

View in article

(a) FTIR spectrum of the grain C-0061 acquired within the Curation Facility with the MicrOmega instrument (Pilorget et al., 2022) and obtained from the Astromaterials Science Research Group (ASRG et al., 2022).

View in article

Such a result also explains both the low water molecule content of the interlayer space of Ryugu grains (0.3 wt. %; Yokoyama et al., 2022) and the lack of a 1.9 μm combination band related to “OH vibrations in H2O molecules” (Pilorget et al., 2022).

View in article

NH4+ phyllosilicates, NH4+ hydrated salts and/or nitrogen-rich organics are the likely candidates to explain the infrared NH signature of Ryugu (Pilorget et al., 2022).

View in article

Takir, D., Emery, J.P. (2012) Outer Main Belt asteroids: Identification and distribution of four 3-μm spectral groups. Icarus 219, 641–654. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2012.02.022

Show in context

Show in context However, such an infrared signature has never been observed in any meteorite on Earth, but strikingly similar signatures are reported for Ceres (King et al., 1992; De Sanctis et al., 2015; Yada et al., 2022) and a few other asteroids (Takir and Emery, 2012).

View in article

Thomas, N., Dionysiou, D.D., Pillai, S.C. (2021) Heterogeneous Fenton catalysts: A review of recent advances. Journal of Hazardous Materials 404, 124082. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124082

Show in context

Show in context Degradation of organic molecules could occur via Fe oxidation of clay minerals by the formation of hydroxyl radicals (•OH) which then degrade organics (Chen et al., 2019; Huang et al., 2020; Thomas et al., 2021).

View in article

Viennet, J.-C., Bernard, S., Le Guillou, C., Jacquemot, P., Balan, E., Delbes, L., Rigaud, B., Georgelin, T., Jaber, M. (2019) Experimental clues for detecting biosignatures on Mars. Geochemical Perspectives Letters 12, 28–33. https://doi.org/10.7185/geochemlet.1931

Show in context

Show in context Such XRD experiments allow investigation of the presence of water molecules or organics within the interlayer space of smectite layers (Viennet et al., 2019, 2020, 2022; Lanson et al., 2022).

View in article

When organic molecules are present within the interlayer space of smectite layers, the layer to layer distance of smectite is modified according to the type of organic molecules and their arrangement (Lagaly et al., 2013) and the organics lock the interlayer space by preventing water molecules from entering (Lagaly et al., 2013; Viennet et al., 2019, 2020, 2022).

View in article

Yet, ammonium-bearing smectites allow the absorption of water molecules within their interlayer space which will give a XRD behaviour similar to the reference smectite considered here (Supplementary Information Fig. S-3) and a collapsed interlayer space at ∼10 Å under 0 % RH (Gautier et al., 2010; Viennet et al., 2019).

View in article

Yet when positively charged, NH organics can compensate the permanent charge of smectite (Lagaly et al., 2013; Viennet et al., 2019, 2020, 2022).

View in article

Viennet, J.-C., Bernard, S., Le Guillou, C., Jacquemot, P., Delbes, L., Balan, E., Jaber, M. (2020) Influence of the nature of the gas phase on the degradation of RNA during fossilization processes. Applied Clay Science 191, 105616. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clay.2020.105616

Show in context

Show in context Such XRD experiments allow investigation of the presence of water molecules or organics within the interlayer space of smectite layers (Viennet et al., 2019, 2020, 2022; Lanson et al., 2022).

View in article

When organic molecules are present within the interlayer space of smectite layers, the layer to layer distance of smectite is modified according to the type of organic molecules and their arrangement (Lagaly et al., 2013) and the organics lock the interlayer space by preventing water molecules from entering (Lagaly et al., 2013; Viennet et al., 2019, 2020, 2022).

View in article

Yet when positively charged, NH organics can compensate the permanent charge of smectite (Lagaly et al., 2013; Viennet et al., 2019, 2020, 2022).

View in article

Viennet, J.-C., Bernard, S., Le Guillou, C., Sautter, V., Grégoire, B., et al. (2021) Martian Magmatic Clay Minerals Forming Vesicles: Perfect Niches for Emerging Life? Astrobiology 21, 605–612. https://doi.org/10.1089/ast.2020.2345

Show in context

Show in context Given the ability of smectite layers to adsorb, concentrate, protect and serve as polymerisation templates for organic molecules, they might play a key role for prebiotic reactions which are necessary steps in the origin of life (Bernal, 1951; Viennet et al., 2021), further increasing the astrobiological potential of the dwarf planet Ceres.

View in article

Viennet, J.-C., Le Guillou, C., Remusat, L., Baron, F., Delbes, L., Blanchenet, A.M., Laurent, B., Criouet, I., Bernard, S. (2022) Experimental investigation of Fe-clay/organic interactions under asteroidal conditions. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 318, 352–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2021.12.002

Show in context

Show in context Such XRD experiments allow investigation of the presence of water molecules or organics within the interlayer space of smectite layers (Viennet et al., 2019, 2020, 2022; Lanson et al., 2022).

View in article

When organic molecules are present within the interlayer space of smectite layers, the layer to layer distance of smectite is modified according to the type of organic molecules and their arrangement (Lagaly et al., 2013) and the organics lock the interlayer space by preventing water molecules from entering (Lagaly et al., 2013; Viennet et al., 2019, 2020, 2022).

View in article

Yet, in presence of smectite, the formation of IOM is inhibited by the fixation of a part of the organic molecules in solution within the interlayer space of smectite, preventing the necessary reaction of polymerisation and condensation steps for the formation of IOM (Viennet et al., 2022).

View in article

Yet when positively charged, NH organics can compensate the permanent charge of smectite (Lagaly et al., 2013; Viennet et al., 2019, 2020, 2022).

View in article

Yada, T., Abe, M., Okada, T., Nakato, A., Yogata, K., et al. (2022) Preliminary analysis of the Hayabusa2 samples returned from C-type asteroid Ryugu. Nature Astronomy 6, 214–220. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-021-01550-6

Show in context

Show in context Ryugu grains share numerous features with the chemically primitive but also highly aqueously altered CI group chondrites (E. Nakamura et al., 2022; T. Nakamura et al., 2022; Yada et al., 2022; Yokoyama et al., 2022), hence offering invaluable insights into the protoplanetary disk and asteroidal alteration processes.

View in article

They also offer a chance to better characterise the terrestrial alteration that CI meteorites underwent since their fall on Earth (Gounelle and Zolensky, 2001; E. Nakamura et al., 2022; T. Nakamura et al., 2022; Yada et al., 2022; Yokoyama et al., 2022).

View in article

A puzzling spectroscopic feature of essentially the entire collection of Ryugu grains is the infrared signature of NH-rich compounds as evidenced by the presence of an absorption band at ∼3.06–3.1 μm (Fig. 1a; Pilorget et al., 2022; Yada et al., 2022).

View in article

However, such an infrared signature has never been observed in any meteorite on Earth, but strikingly similar signatures are reported for Ceres (King et al., 1992; De Sanctis et al., 2015; Yada et al., 2022) and a few other asteroids (Takir and Emery, 2012).

View in article

This is consistent with the Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) feature at 2.7 μm related to metal-OH vibration of trioctahedral clay minerals (Fig. 1a; Pilorget et al., 2022; Yada et al., 2022) and with their Mg-rich chemical composition (E. Nakamura et al., 2022; T. Nakamura et al., 2022).

View in article

Given the strong geochemical, mineralogical and petrological similarities between the Orgueil meteorite and the grains of Ryugu (E. Nakamura et al., 2022; T. Nakamura et al., 2022; Yada et al., 2022), it appears unlikely that this difference could be explained in terms of asteroidal geochemical processes.

View in article

By extension, we propose that the reflectance spectra of Ceres may be interpreted as a signature of NH-rich organics within the interlayer space of phyllosilicates instead of NH4+ (King et al., 1992; De Sanctis et al., 2015; Yada et al., 2022).

View in article

Yokoyama, T., Nagashima, K., Nakai, I., Young, E.D., Abe, Y., et al. (2022) Samples returned from the asteroid Ryugu are similar to Ivuna-type carbonaceous meteorites. Science 379, eabn7850. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abn7850

Show in context

Show in context Ryugu grains share numerous features with the chemically primitive but also highly aqueously altered CI group chondrites (E. Nakamura et al., 2022; T. Nakamura et al., 2022; Yada et al., 2022; Yokoyama et al., 2022), hence offering invaluable insights into the protoplanetary disk and asteroidal alteration processes.

View in article

However, based on thermogravimetric analyses coupled with mass spectrometry on representative Ryugu grains (Yokoyama et al., 2022), the water molecule content within the interlayer space of smectite in the Ryugu samples is low (<0.3 wt. %).

View in article

Such a result also explains both the low water molecule content of the interlayer space of Ryugu grains (0.3 wt. %; Yokoyama et al., 2022) and the lack of a 1.9 μm combination band related to “OH vibrations in H2O molecules” (Pilorget et al., 2022).

View in article

They also offer a chance to better characterise the terrestrial alteration that CI meteorites underwent since their fall on Earth (Gounelle and Zolensky, 2001; E. Nakamura et al., 2022; T. Nakamura et al., 2022; Yada et al., 2022; Yokoyama et al., 2022).

View in article

top

Supplementary Information

The Supplementary Information includes:

Download the Supplementary Information (PDF)

Figures

Figure 1 (a) FTIR spectrum of the grain C-0061 acquired within the Curation Facility with the MicrOmega instrument (Pilorget et al., 2022

Pilorget, C., Okada, T., Hamm, V., Brunetto, R., Yada, T., et al. (2022) First compositional analysis of Ryugu samples by the MicrOmega hyperspectral microscope. Nature Astronomy 6, 221–225. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-021-01549-z

) and obtained from the Astromaterials Science Research Group (ASRG et al., 2022Astromaterials Science Research Group (ASRG), Institute of Space and Astronautical Science (ISAS), Institut d’Astrophysique Spatiale (IAS), Yumoto, K., Yabe, Y., Cho, Y., Sugita, S. (2022) Hayabusa2, Ryugu Sample Curatorial Dataset. ISAS/JAXA, Japan. https://doi.org/10.17597/ISAS.DARTS/CUR-Ryugu-description

). (b) XRD measurements and the corresponding peak assignation of the grain C-0061 under “raw” and 0 % relative humidity conditions.

Figure 2 XRD measurements and the corresponding peak assignation of the 00ℓ reflections of the smectite layers of the grain C-0061 under “raw” and 0 % relative humidity (RH) conditions. The arrows indicate the XRD behaviour of the two smectite phases after exposure to 0 % RH.

Figure 3 XRD measurements and the corresponding peak assignation of the 001 reflection of the smectite layers of Orgueil under “raw” and 0 % relative humidity conditions.