The chemical conditions necessary for the formation of microbialites

Affiliations | Corresponding Author | Cite as | Funding information- Share this article

-

Article views:156Cumulative count of HTML views and PDF downloads.

- Download Citation

- Rights & Permissions

top

Abstract

Figures

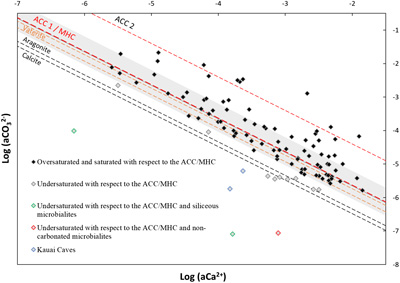

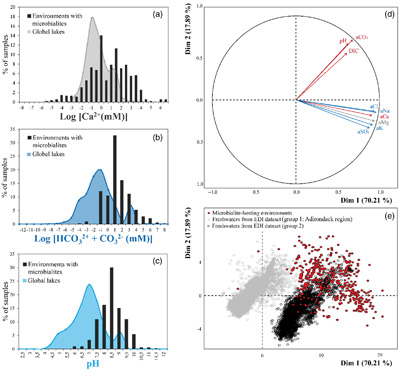

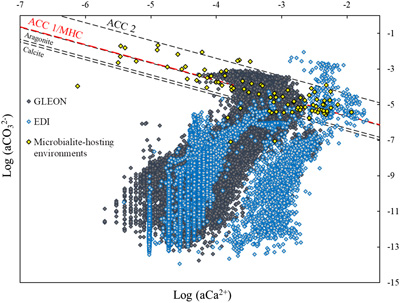

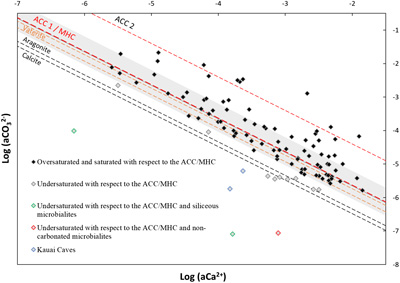

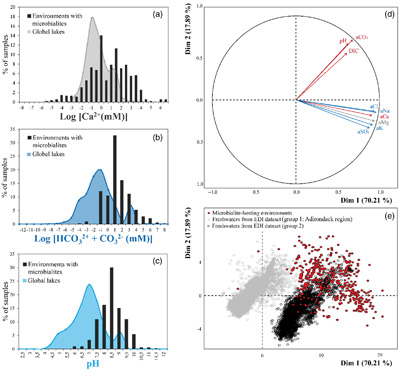

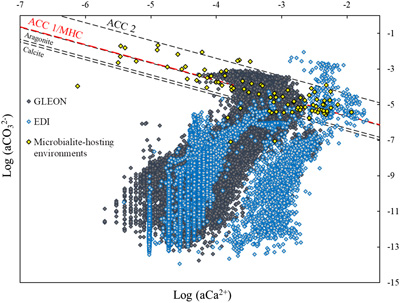

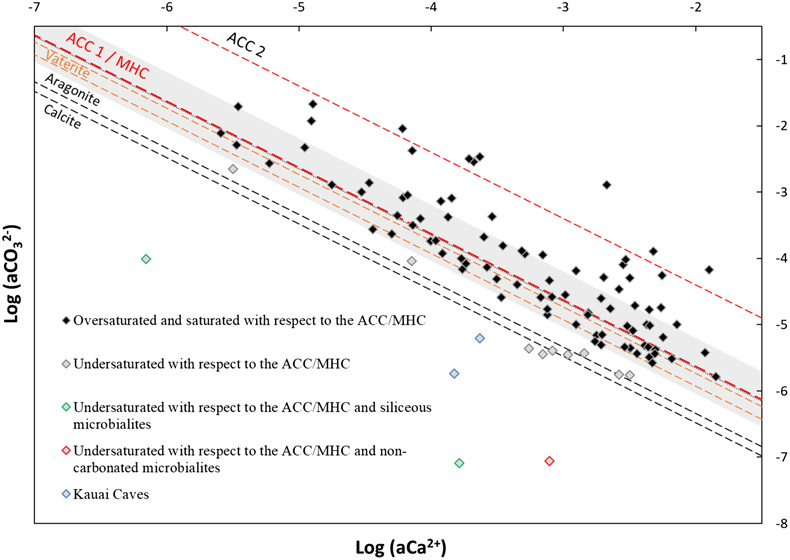

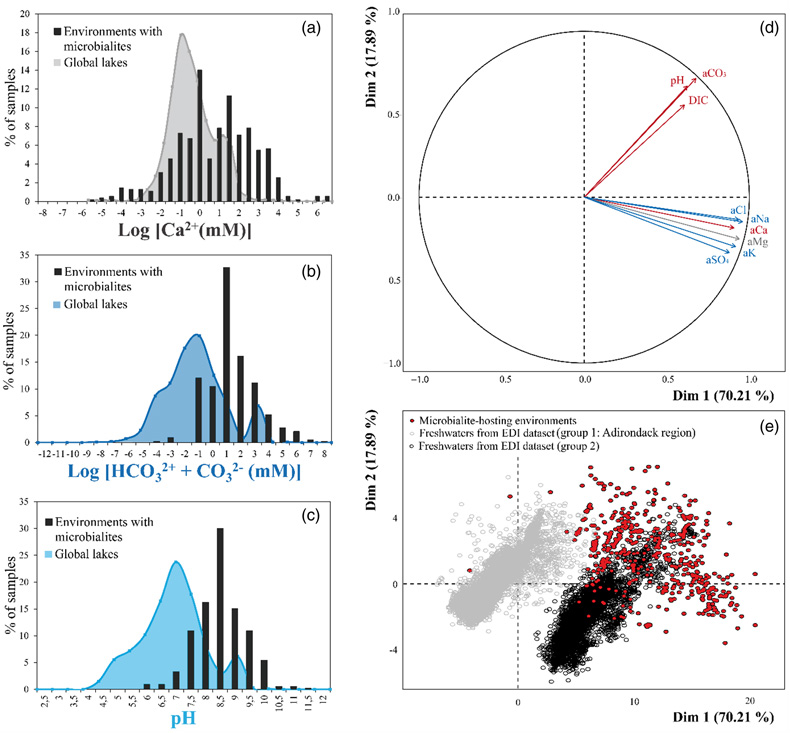

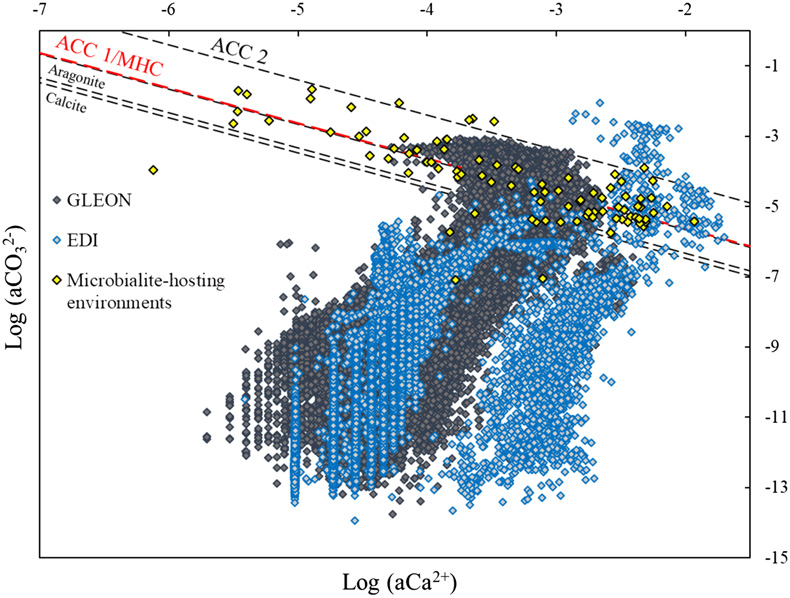

Figure 1 Plot of the log of the activities of CO32− vs. Ca2+ for 102 microbialite-hosting environments. Solubility lines (dashed lines) are reported for calcite (logKs = −8.48), aragonite (logKs = −8.34), monohydrocalcite (MHC; logKs = −7.6), vaterite (De Visscher and Vanderdeelen, 2003), ACC1 as reported by Kellermeier et al. (2014; logKs = −7.63) and ACC2 as reported by Brečević and Nielsen (1989; logKs = −6.39). Only mean values are provided for each environment by a diamond. Green diamonds correspond to siliceous microbialites; red diamond corresponds to a clayey microbialite. Black diamonds correspond to environments saturated and oversaturated with ACC1 and/or vaterite; grey diamonds correspond to environments undersaturated with vaterite. The grey shaded zone highlights a 95 % confidence interval on the saturation values of microbialite-hosting environments with respect to ACC1/MHC. |  Figure 2 Comparison of the microbialite-hosting environments and lakes in the EDI and GLEON databases. Compared distributions are (a) the log [Ca2+(mM)], (b) the log [HCO3− + CO32− (mM)] and (c) the pH of the microbialite-hosting environments (black bars) and the EDI and GLEON databases (grey or blue surface). Ca2+ activities were calculated using all major ion concentrations in the EDI database, whereas they were approximated to concentrations in the GLEON database. Errors due to this approximation are estimated to be minor (Fig. S-7). (d) Correlation circle from the global PCA of the physico-chemical parameters of EDI lakes and microbialite solutions. The logarithms of the activities and DIC were used. The colours correspond to those used to differentiate the principal components on the microbialite-hosting environments PCA (Fig. S-4). (e) Plot of all aqueous environments hosting microbialites (red dots) and from the EDI database (black and grey dots) along the two main dimensions of the ACP. |  Figure 3 Plot of the activity of CO32− vs. Ca2+ for all lakes from the EDI (blue diamonds), GLEON (grey diamonds) and microbialite-hosting environments (yellow diamonds) datasets. Solubility lines of aragonite, calcite, monohydrocalcite and ACC are the same as in Figure 1. |

| Figure 1 | Figure 2 | Figure 3 |

top

Introduction

Microbialites are organosedimentary deposits formed by benthic microbial communities that mediate authigenic mineral precipitation (Burne and Moore, 1987

Burne, R.V., Moore, L.S. (1987) Microbialites: organosedimentary deposits of benthic microbial communities. PALAIOS 2, 241–254. https://doi.org/10.2307/3514674

). They are found throughout the geological record up to 3.43 billion years ago and are considered as among the oldest traces of life on Earth (Allwood et al., 2007Allwood, A.C., Walter, M.R., Burch, I.W., Kamber, B.S. (2007) 3.43 billion-year-old stromatolite reef from the Pilbara Craton of Western Australia: Ecosystem-scale insights to early life on Earth. Precambrian Research 158, 198–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.precamres.2007.04.013

). It has been argued that the diversity of microbialites has varied over geological time with an overall decline at the end of the Proterozoic (e.g., Awramik, 1971Awramik, S.M. (1971) Precambrian Columnar Stromatolite Diversity: Reflection of Metazoan Appearance. Science 174, 825–827. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.174.4011.825

). The causes of these fluctuations have fed debates opposing two major models: (i) one involving biotic causes suggests that grazing by Metazoans induced the decline of microbialites (Walter and Heys, 1985Walter, M.R., Heys, G.R. (1985) Links between the rise of the metazoa and the decline of stromatolites. Precambrian Research 29, 149–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/0301-9268(85)90066-X

), and (ii) a second “abiotic” model proposes that changes in the chemical composition of the ocean were responsible for microbialite decline (Fischer, 1965Fischer, A.G. (1965) Fossils, early life, and atmospheric history. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 53, 1205–1215. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.53.6.1205-a

; Kempe and Kaźmierczak, 1994Kempe, S., Kaźmierczak, J. (1994) The role of alkalinity in the evolution of ocean chemistry, organization of living systems, and biocalcification processes. In: Doumenge, F. (Ed.) Past and Present Biomineralization Processes. Considerations about the Carbonate Cycle. IUCN – COE Workshop, 15–16 November 1993, Monaco. Bulletin de l’Institut océanographique, Monaco, numéro special 13, 61–117.

; Peters et al., 2017Peters, S.E., Husson, J.M., Wilcots, J. (2017) The rise and fall of stromatolites in shallow marine environments. Geology 45, 487–490. https://doi.org/10.1130/G38931.1

).While this debate is difficult to directly tackle, it emphasises that we still do not understand the conditions necessary for microbialites to form. Modern microbialites have been described in diverse environments (e.g., marine, freshwater, hypersaline) and in the presence of very diverse microbial communities (e.g., Iniesto et al., 2021

Iniesto, M., Moreira, D., Reboul, G., Deschamps, P., Benzerara, K., Bertolino, P., Saghaï, A., Tavera, R., López-García, P. (2021) Core microbial communities of lacustrine microbialites sampled along an alkalinity gradient. Environmental Microbiology 23, 51–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/1462-2920.15252

). Presently, there are many reports in the literature characterising the aqueous geochemistry of single sites where modern microbialites form. However, only a few meta-analyses gathering some of these data provide a broader, statistical overview (e.g., Zeyen et al., 2021Zeyen, N., Benzerara, K., Beyssac, O., Daval, D., Muller, E., et al. (2021) Integrative analysis of the mineralogical and chemical composition of modern microbialites from ten Mexican lakes: What do we learn about their formation? Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 305, 148–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2021.04.030

). Here, we achieve an unprecedented compilation of datasets from 140 locations where modern microbialites form, spanning freshwater, brackish, saline and hypersaline environments (Table S-1). We analyse the variability of the chemical parameters of microbialite-hosting environments and look for possible invariants. Moreover, in order to assess the rareness/commonness of conditions encountered in microbialite-hosting environments, we compare our database with two databases of continental aqueous systems.top

Results

Physico-chemical parameters of microbialite-hosting environments. The compilation was achieved by systematically searching the terms “stromatolite”, “thrombolite” or “microbialite” in the literature (see Supplementary Information). The 140 compiled modern microbialite-hosting systems occur on all continents (Fig. S-1) in a diversity of climates and geological contexts. Most of the environments were freshwater, but 34 were marine. The database includes emblematic microbialites, such as those of Shark Bay, Lagoa Vermelha or the Bahamas, that have received much attention as modern analogues of ancient microbialites. Dissolved Ca2+ and Mg2+ concentrations were measured in a majority (∼90 %) of the corresponding aqueous solutions and ranged from 0.001 to 643 mM and 0.001 to 1325 mM, respectively. Concentrations of other major chemical species (Na+, Cl−, K+, SO42−) were also generally well documented (∼88 % of systems on average). Measurements of the dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) concentrations ranged between 0.022 and 6236 mM. These measurements were less documented (∼76 % of systems) in the database, despite their importance in carbonate-rich environments. In seven lakes, alkalinity values were available and assumed to be equal to DIC (Dickson et al., 1981

Dickson, A.G. (1981) An exact definition of total alkalinity and a procedure for the estimation of alkalinity and total inorganic carbon from titration data. Deep Sea Research Part A. Oceanographic Research Papers 28, 609–623. https://doi.org/10.1016/0198-0149(81)90121-7

; Fig. S-2).Overall, microbialite-forming waters in our database span a high diversity of water chemical types as defined by Boros and Kolpakova (2018)

Boros, E., Kolpakova, M. (2018) A review of the defining chemical properties of soda lakes and pans: An assessment on a large geographic scale of Eurasian inland saline surface waters. PLoS ONE 13, e0202205. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202205

, which were: saline (53 % of the occurrences), soda-saline (23 % of the occurrences) and soda (24 % of occurrences) (Fig. S-3). Principal component analyses (PCA) were conducted on 10 chemical variables measured on 545 samples of microbialite-hosting environments in order to find the variables contributing to most of the dataset variability. It showed that most of the variance (∼62 %) in the dataset was explained by (i) salinity (logarithms of Na, Cl, K activities) (35.22 %), and (ii) the logarithm of CO32− activity anticorrelated with the logarithm of Ca2+ activity (26.32 %) (Fig. S-4).Assessment of the saturation index of waters in which modern microbialites form. The anticorrelation between Ca2+ and CO32− activities was further analysed by plotting their logarithms against each other. This plot also allows us to assess the saturation index (defined as SI = log(IAP/Ks), where IAP is the ion activity product and Ks is the solubility constant) of solutions with various CaCO3 phases such as anhydrous crystalline phases and amorphous phases (ACC). Four hundred and sixteen chemical measurements performed on 102 microbialite-forming environments that were available in the database. The mean value was considered for the environments for which several measurements were available (Fig. 1). Conclusions were similar when using the median.

Figure 1 Plot of the log of the activities of CO32− vs. Ca2+ for 102 microbialite-hosting environments. Solubility lines (dashed lines) are reported for calcite (logKs = −8.48), aragonite (logKs = −8.34), monohydrocalcite (MHC; logKs = −7.6), vaterite (De Visscher and Vanderdeelen, 2003

De Visscher, A., Vanderdeelen, J. (2003) Estimation of the Solubility Constant of Calcite, Aragonite, and Vaterite at 25°C Based on Primary Data Using the Pitzer Ion Interaction Approach. Monatshefte für Chemie/Chemical Monthly 134, 769–775. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00706-002-0587-3

), ACC1 as reported by Kellermeier et al. (2014Kellermeier, M., Picker, A., Kempter, A., Cölfen, H., Gebauer, D. (2014) A Straightforward Treatment of Activity in Aqueous CaCO3 Solutions and the Consequences for Nucleation Theory. Advanced Materials 26, 752–757. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201303643

; logKs = −7.63) and ACC2 as reported by Brečević and Nielsen (1989Brečević, L., Nielsen, A.E. (1989) Solubility of amorphous calcium carbonate. Journal of Crystal Growth 98, 504–510. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-0248(89)90168-1

; logKs = −6.39). Only mean values are provided for each environment by a diamond. Green diamonds correspond to siliceous microbialites; red diamond corresponds to a clayey microbialite. Black diamonds correspond to environments saturated and oversaturated with ACC1 and/or vaterite; grey diamonds correspond to environments undersaturated with vaterite. The grey shaded zone highlights a 95 % confidence interval on the saturation values of microbialite-hosting environments with respect to ACC1/MHC.A large majority (89 %) of aqueous environments were highly supersaturated with respect to calcite and aragonite and aligned between the solubility lines of vaterite and an ACC phase (ACC2) as determined by Brečević and Nielsen (1989)

Brečević, L., Nielsen, A.E. (1989) Solubility of amorphous calcium carbonate. Journal of Crystal Growth 98, 504–510. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-0248(89)90168-1

(Fig. 1). Diverse ACC phases exist with logKs varying between −7.63 and −6.04. Here, many points align close to the solubility lines of MHC and ACC1 phase (another ACC phase as determined by Kellermeier et al., 2014Kellermeier, M., Picker, A., Kempter, A., Cölfen, H., Gebauer, D. (2014) A Straightforward Treatment of Activity in Aqueous CaCO3 Solutions and the Consequences for Nucleation Theory. Advanced Materials 26, 752–757. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201303643

).A few environments (n = 5) appeared significantly undersaturated with calcite. However, three of them harboured microbialites that were siliceous (e.g., Great Obsidian Pool, Mound Spring; Table S-1) or formed by pure trapping and binding of clays (e.g., Lake Untersee, Antarctica; Table S-1). In two others (Kauai caves, Hawaii), microbialites formed on cave walls in freshwater seeping out of basalts and may experience significant chemical variations by evaporation and CO2 degassing (Léveillé et al., 2007

Léveillé, R.J., Longstaffe, F.J., Fyfe, W.S. (2007) An isotopic and geochemical study of carbonate-clay mineralization in basaltic caves: abiotic versus microbial processes. Geobiology 5, 235–249. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1472-4669.2007.00109.x

).Finally, some environments hosting carbonate microbialites were on average supersaturated with anhydrous carbonates but undersaturated with ACC and vaterite (n = 9; Figs. 1, S-5). Only one single analysis was available for Ciocaia drill (Romania). However, several ones were available for the other locations. For Pavilion Lake, solution geochemistry varied over time, reaching saturation with ACC at certain periods (Fig. S-5). For Lake Kelly, none of the several available measurements were saturated with ACC but it was reported that microbialites may no longer actively form (Lim et al., 2009

Lim, D.S.S., Laval, B.E., Slater, G., Antoniades, D., Forrest, A.L., et al. (2009) Limnology of Pavilion Lake, B. C., Canada – Characterization of a microbialite forming environment. Fundamental and Applied Limnology/Archiv für Hydrobiologie 173, 329–351. https://doi.org/10.1127/1863-9135/2009/0173-0329

). Last, at least four other environments showed spatial chemical heterogeneities. They were undersaturated with ACC on average but supersaturated with ACC at certain locations. For example, Lakes Joyce and Hoare (Antarctica) have chemically stratified waters, and microbialites form at depths where DIC water content rises (Mackey et al., 2018Mackey, T.J., Sumner, D.Y., Hawes, I., Leidman, S.Z., Andersen, D.T., Jungblut, A.D. (2018) Stromatolite records of environmental change in perennially ice-covered Lake Joyce, McMurdo Dry Valleys, Antarctica. Biogeochemistry 137, 73–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-017-0402-1

). Pastos Grandes (Bolivia) harbours groundwater outflows chemically evolving by evaporation along their travel away from the source. Microbialites form when water reaches saturation with ACC (Muller et al., 2022Muller, E., Ader, M., Aloisi, G., Bougeault, C., Durlet, C., et al. (2022) Successive Modes of Carbonate Precipitation in Microbialites along the Hydrothermal Spring of La Salsa in Laguna Pastos Grandes (Bolivian Altiplano). Geosciences 12, 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences12020088

). Overall, 98 % of aqueous environments hosting modern microbialites were saturated with ACC at least part of the time.Comparison of the chemistry of modern microbialite-hosting aqueous solutions with two global freshwater databases. The chemical compositions of carbonate microbialite-hosting environments were compared with many aqueous environments listed in two general databases, in order to assess how unique the former might be. The Global Lake Ecological Observatory Network (GLEON) database compiles 105,678 samples from 6422 North European lakes with only temperature, pH, DIC and Ca2+ concentrations as physico-chemical parameters (Weyhenmeyer et al., 2019

Weyhenmeyer, G.A., Hartmann, J., Hessen, D.O., Kopáček, J., Hejzlar, J., et al. (2019) Widespread diminishing anthropogenic effects on calcium in freshwaters. Scientific Reports 9, 10450. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-46838-w

; see Supplementary Information). The Environmental Data Initiative (EDI) groups 28,455 samples from 1547 North American lakes with several additional parameters (Supplementary Information). Some of the lakes compiled in the EDI and GLEON databases possibly harbour microbialites but if this is the case, they have not been described in the literature and therefore are not in our microbialites database. The comparison showed that pH, DIC and calcium concentrations in the carbonate microbialite database were significantly higher on average than in lakes from the GLEON and EDI databases (Wilcoxon comparison tests of means; threshold of 0.05 and p values of 0, 2.1 × 10−210 and 3.8 × 10−175, respectively) (Figs. 2a–c, 3 and S-6). A principal component analyses on the physico-chemical parameters from EDI and microbialite-hosting environments databases outlined that ∼88 % of the variance of all these aqueous environments is explained by the activity of Cl− or Ca2+ (70.2 % of the variability) and DIC (17.9 %) (Fig. 2d). The EDI lakes spread as two groups in the plot of the two PCA dimensions. One group contains Adirondack region lakes (USA), including Mirror Lake, New York, whereas the second group is composed of all other more saline lakes. In this plot, microbialite-forming solutions mostly plot separately and stretch orthogonally to the freshwaters from the EDI database (Fig. 2e). GLEON data were not included in this PCA analysis, because too many parameters were missing.

Figure 2 Comparison of the microbialite-hosting environments and lakes in the EDI and GLEON databases. Compared distributions are (a) the log [Ca2+(mM)], (b) the log [HCO3− + CO32− (mM)] and (c) the pH of the microbialite-hosting environments (black bars) and the EDI and GLEON databases (grey or blue surface). Ca2+ activities were calculated using all major ion concentrations in the EDI database, whereas they were approximated to concentrations in the GLEON database. Errors due to this approximation are estimated to be minor (Fig. S-7). (d) Correlation circle from the global PCA of the physico-chemical parameters of EDI lakes and microbialite solutions. The logarithms of the activities and DIC were used. The colours correspond to those used to differentiate the principal components on the microbialite-hosting environments PCA (Fig. S-4). (e) Plot of all aqueous environments hosting microbialites (red dots) and from the EDI database (black and grey dots) along the two main dimensions of the ACP.

Figure 3 Plot of the activity of CO32− vs. Ca2+ for all lakes from the EDI (blue diamonds), GLEON (grey diamonds) and microbialite-hosting environments (yellow diamonds) datasets. Solubility lines of aragonite, calcite, monohydrocalcite and ACC are the same as in Figure 1.

Finally, by plotting the EDI and GLEON environments in the CaCO3 solubility diagram, less than 5 % of them show saturation with ACC/MHC (Fig. 3).

top

Discussion

Saturation with vaterite/ACC/MHC as a necessary condition for the formation of microbialites. The need for a relatively high apparent critical saturation of the solutions so that microbialites form is suggested by the analysis of the compiled database. Arp et al. (2001)

Arp, G., Reimer, A., Reitner, J. (2001) Photosynthesis-Induced Biofilm Calcification and Calcium Concentrations in Phanerozoic Oceans. Science 292, 1701–1704. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1057204

argued that a SI of ∼1 relative to calcite was required for biofilm calcification to occur, based on the study of modern non-marine calcifying cyanobacterial biofilms. Such a value approximately corresponds to the solubilities of vaterite, ACC1 or MHC. Moreover, Fukushi et al. (2020)Fukushi, K., Imai, E., Sekine, Y., Kitajima, T., Gankhurel, B., Davaasuren, D., Hasebe, N. (2020) In Situ Formation of Monohydrocalcite in Alkaline Saline Lakes of the Valley of Gobi Lakes: Prediction for Mg, Ca, and Total Dissolved Carbonate Concentrations in Enceladus’ Ocean and Alkaline-Carbonate Ocean Worlds. Minerals 10, 669. https://doi.org/10.3390/min10080669

observed that several alkaline lakes were saturated with MHC and suggested this phase as a precursor of anhydrous carbonates. Accordingly, many microbialite-hosting environments in our database are alkaline. More recently, the same observation was done by Zeyen et al. (2021)Zeyen, N., Benzerara, K., Beyssac, O., Daval, D., Muller, E., et al. (2021) Integrative analysis of the mineralogical and chemical composition of modern microbialites from ten Mexican lakes: What do we learn about their formation? Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 305, 148–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2021.04.030

in microbialite-hosting lakes in Mexico, who suggested ACC as an alternative precursor. In order to explain these observations, they proposed that ACC may precipitate first, before transforming to the less soluble MHC, then anhydrous carbonate phases, including vaterite. Here, based on a new database of 140 microbialite-bearing systems, encompassing freshwater, saline and hypersaline conditions, we generalise this observation to all environments where microbialites form, suggesting that saturation with ACC1/MHC or with vaterite appears as a necessary condition for the formation of modern microbialites. This model may be further adjusted in the future. The ACC1 solubility line reported in Figure 1 is a lower bound for ACC. Indeed, the solubility of ACC increases with the Mg content (Mergelsberg et al., 2020Mergelsberg, S.T., De Yoreo, J.J., Miller, Q.R.S., Michel, F.M., Ulrich, R.N., Dove, P.M. (2020) Metastable solubility and local structure of amorphous calcium carbonate (ACC). Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 289, 196–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2020.06.030

). According to Blue and Dove (2015)Blue, C.R., Dove, P.M. (2015) Chemical controls on the magnesium content of amorphous calcium carbonate. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 148, 23–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2014.08.003

, the partition coefficient Kd of Mg vs. Ca in ACC is constant (0.047) for pH below 9.5. Based on this, the Mg/Ca ratio in ACC possibly formed in microbialite-bearing systems ranges between 0.012 and 225, which may correspond to a variation in solubility by ∼1 log unit.Several conditions may allow the achievement of relatively high SI values with CaCO3 as observed in microbialite-hosting environments. Aqueous alkaline environments are fed by fluxes of Ca2+ and HCO3− ions, e.g., from water-rock interactions, and/or atmospheric inputs (Pulido-Villena et al., 2006

Pulido-Villena, E., Reche, I., Morales-Baquero, R. (2006) Significance of atmospheric inputs of calcium over the southwestern Mediterranean region: High mountain lakes as tools for detection. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 20, GB2012. https://doi.org/10.1029/2005GB002662

). This generally does not directly create high saturation conditions, except when locally, e.g., Ca2+-rich groundwater outflows in high DIC lakes such as in Lake Van (Shapley et al., 2005Shapley, M.D., Ito, E., Donovan, J.J. (2005) Authigenic calcium carbonate flux in groundwater-controlled lakes: Implications for lacustrine paleoclimate records. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 69, 2517–2533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2004.12.001

). In many cases, evaporation is a major driver for concentrating solutions and achieving high saturation with CaCO3 (Pecoraino et al., 2015Pecoraino, G., D’Alessandro, W., Inguaggiato, S. (2015) The Other Side of the Coin: Geochemistry of Alkaline Lakes in Volcanic Areas. In: Rouwet, D., Christenson, B., Tassi, F., Vandemeulebrouck, J. (Eds.) Volcanic Lakes. Advances in Volcanology, Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 219–237. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-36833-2_9

). This is consistent with the abundance of microbialites in saline environments. The SI values of aqueous solutions are not controlled by the precipitation of crystalline anhydrous CaCO3, which are the least soluble CaCO3 phases. Instead, SI values are higher. Recently, Pietzsch et al. (2022)Pietzsch, R., Tosca, N.J., Gomes, J.P., Roest-Ellis, S., Sartorato, A.C.L., Tonietto, S.N. (2022) The role of phosphate on non-skeletal carbonate production in a Cretaceous alkaline lake. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 317, 365–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2021.09.032

, suggested that in some alkaline lakes, orthophosphate concentrations are high and inhibit crystalline anhydrous CaCO3 precipitation, allowing the onset of saturation levels as high as the solubility of ACC. Unfortunately, this cannot be further tested here since dissolved PO42− concentrations are only reported in eleven microbialite-forming environments of our database. Similarly, the role of exopolymeric substances (EPS) in locally controlling SI values could be questioned. Whether this inhibition may be a major process in all reported microbialite-hosting environments will require further data acquisition. Once Ca2+ and CO32− activities reach values high enough so that MHC/ACC solubility is attained, we hypothesise that any further input of Ca2+ and/or DIC to the system can contribute to the accumulation of carbonates, partly as microbialites, helping to control their overall abundance in the aqueous system.Another outcome of the present analyses is that they may help in finding localities where modern microbialites have been potentially overlooked so far, by screening aqueous environments based on their SI with CaCO3 (Fig. 3). Some environments listed in the GLEON and EDI databases are saturated with ACC/MHC. However, we presently do not know if they host microbialites. Two options are possible: (i) all these environments host microbialites, which would imply that saturation with ACC/MHC is a necessary and sufficient condition for microbialite formation; and (ii) some of these environments do not contain microbialites, which means that some other conditions may be necessary in addition to saturation with ACC/MHC to form microbialites.

Presently, it may be speculated that changes in seawater chemistry, possibly at the end of the Proterozoic, from ACC-saturated to ACC-undersaturated seawater, may have caused the decline of microbialite abundances (Fig. S-8). However, to be validated, this speculation will need further constraints on the value of SIACC in past oceans.

Finally, a control of water chemistry by MHC/ACC precipitation as a necessary condition for the growth of microbialites does not mean that microbial communities or any biological parameter have no impact at all in the formation of microbialites. Instead, it suggests that in order for them to participate in authigenic microbialite formation, at least some specific physico-chemical environmental conditions, i.e. saturation with ACC/MHC, must be met.

top

Acknowledgements

This project received financial support from the CNRS through the MITI interdisciplinary programs and the ANR Microbialites. The authors thank Elodie Muller and Nina Zeyen for their help on setting up of the dataset. JC is funded by a grant from the Interface pour le vivant doctorate programme at Sorbonne Université.

Editor: Satish Myneni

top

References

Allwood, A.C., Walter, M.R., Burch, I.W., Kamber, B.S. (2007) 3.43 billion-year-old stromatolite reef from the Pilbara Craton of Western Australia: Ecosystem-scale insights to early life on Earth. Precambrian Research 158, 198–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.precamres.2007.04.013

Show in context

Show in context They are found throughout the geological record up to 3.43 billion years ago and are considered as among the oldest traces of life on Earth (Allwood et al., 2007).

View in article

Arp, G., Reimer, A., Reitner, J. (2001) Photosynthesis-Induced Biofilm Calcification and Calcium Concentrations in Phanerozoic Oceans. Science 292, 1701–1704. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1057204

Show in context

Show in context Arp et al. (2001) argued that a SI of ∼1 relative to calcite was required for biofilm calcification to occur, based on the study of modern non-marine calcifying cyanobacterial biofilms.

View in article

Awramik, S.M. (1971) Precambrian Columnar Stromatolite Diversity: Reflection of Metazoan Appearance. Science 174, 825–827. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.174.4011.825

Show in context

Show in context It has been argued that the diversity of microbialites has varied over geological time with an overall decline at the end of the Proterozoic (e.g., Awramik, 1971).

View in article

Blue, C.R., Dove, P.M. (2015) Chemical controls on the magnesium content of amorphous calcium carbonate. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 148, 23–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2014.08.003

Show in context

Show in context According to Blue and Dove (2015), the partition coefficient Kd of Mg vs. Ca in ACC is constant (0.047) for pH below 9.5.

View in article

Boros, E., Kolpakova, M. (2018) A review of the defining chemical properties of soda lakes and pans: An assessment on a large geographic scale of Eurasian inland saline surface waters. PLoS ONE 13, e0202205. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202205

Show in context

Show in context Overall, microbialite-forming waters in our database span a high diversity of water chemical types as defined by Boros and Kolpakova (2018), which were: saline (53 % of the occurrences), soda-saline (23 % of the occurrences) and soda (24 % of occurrences) (Fig. S-3).

View in article

Brečević, L., Nielsen, A.E. (1989) Solubility of amorphous calcium carbonate. Journal of Crystal Growth 98, 504–510. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-0248(89)90168-1

Show in context

Show in context Plot of the log of the activities of CO32− vs. Ca2+ for 102 microbialite-hosting environments. Solubility lines (dashed lines) are reported for calcite (logKs = −8.48), aragonite (logKs = −8.34), monohydrocalcite (MHC; logKs = −7.6), vaterite (De Visscher and Vanderdeelen, 2003), ACC1 as reported by Kellermeier et al. (2014; logKs = −7.63) and ACC2 as reported by Brečević and Nielsen (1989; logKs = −6.39).

View in article

A large majority (89 %) of aqueous environments were highly supersaturated with respect to calcite and aragonite and aligned between the solubility lines of vaterite and an ACC phase (ACC2) as determined by Brečević and Nielsen (1989) (Fig. 1).

View in article

Burne, R.V., Moore, L.S. (1987) Microbialites: organosedimentary deposits of benthic microbial communities. PALAIOS 2, 241–254. https://doi.org/10.2307/3514674

Show in context

Show in context Microbialites are organosedimentary deposits formed by benthic microbial communities that mediate authigenic mineral precipitation (Burne and Moore, 1987).

View in article

De Visscher, A., Vanderdeelen, J. (2003) Estimation of the Solubility Constant of Calcite, Aragonite, and Vaterite at 25°C Based on Primary Data Using the Pitzer Ion Interaction Approach. Monatshefte für Chemie/Chemical Monthly 134, 769–775. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00706-002-0587-3

Show in context

Show in context Plot of the log of the activities of CO32− vs. Ca2+ for 102 microbialite-hosting environments. Solubility lines (dashed lines) are reported for calcite (logKs = −8.48), aragonite (logKs = −8.34), monohydrocalcite (MHC; logKs = −7.6), vaterite (De Visscher and Vanderdeelen, 2003), ACC1 as reported by Kellermeier et al. (2014; logKs = −7.63) and ACC2 as reported by Brečević and Nielsen (1989; logKs = −6.39).

View in article

Dickson, A.G. (1981) An exact definition of total alkalinity and a procedure for the estimation of alkalinity and total inorganic carbon from titration data. Deep Sea Research Part A. Oceanographic Research Papers 28, 609–623. https://doi.org/10.1016/0198-0149(81)90121-7

Show in context

Show in context In seven lakes, alkalinity values were available and assumed to be equal to DIC (Dickson et al., 1981; Fig. S-2).

View in article

Fischer, A.G. (1965) Fossils, early life, and atmospheric history. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 53, 1205–1215. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.53.6.1205-a

Show in context

Show in context The causes of these fluctuations have fed debates opposing two major models: (i) one involving biotic causes suggests that grazing by Metazoans induced the decline of microbialites (Walter and Heys, 1985), and (ii) a second “abiotic” model proposes that changes in the chemical composition of the ocean were responsible for microbialite decline (Fischer, 1965; Kempe and Kaźmierczak, 1994; Peters et al., 2017).

View in article

Fukushi, K., Imai, E., Sekine, Y., Kitajima, T., Gankhurel, B., Davaasuren, D., Hasebe, N. (2020) In Situ Formation of Monohydrocalcite in Alkaline Saline Lakes of the Valley of Gobi Lakes: Prediction for Mg, Ca, and Total Dissolved Carbonate Concentrations in Enceladus’ Ocean and Alkaline-Carbonate Ocean Worlds. Minerals 10, 669. https://doi.org/10.3390/min10080669

Show in context

Show in context Moreover, Fukushi et al. (2020) observed that several alkaline lakes were saturated with MHC and suggested this phase as a precursor of anhydrous carbonates.

View in article

Iniesto, M., Moreira, D., Reboul, G., Deschamps, P., Benzerara, K., Bertolino, P., Saghaï, A., Tavera, R., López-García, P. (2021) Core microbial communities of lacustrine microbialites sampled along an alkalinity gradient. Environmental Microbiology 23, 51–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/1462-2920.15252

Show in context

Show in context Modern microbialites have been described in diverse environments (e.g., marine, freshwater, hypersaline) and in the presence of very diverse microbial communities (e.g., Iniesto et al., 2021).

View in article

Kellermeier, M., Picker, A., Kempter, A., Cölfen, H., Gebauer, D. (2014) A Straightforward Treatment of Activity in Aqueous CaCO3 Solutions and the Consequences for Nucleation Theory. Advanced Materials 26, 752–757. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201303643

Show in context

Show in context Diverse ACC phases exist with logKs varying between −7.63 and −6.04. Here, many points align close to the solubility lines of MHC and ACC1 phase (another ACC phase as determined by Kellermeier et al., 2014).

View in article

Plot of the log of the activities of CO32− vs. Ca2+ for 102 microbialite-hosting environments. Solubility lines (dashed lines) are reported for calcite (logKs = −8.48), aragonite (logKs = −8.34), monohydrocalcite (MHC; logKs = −7.6), vaterite (De Visscher and Vanderdeelen, 2003), ACC1 as reported by Kellermeier et al. (2014; logKs = −7.63) and ACC2 as reported by Brečević and Nielsen (1989; logKs = −6.39).

View in article

Kempe, S., Kaźmierczak, J. (1994) The role of alkalinity in the evolution of ocean chemistry, organization of living systems, and biocalcification processes. In: Doumenge, F. (Ed.) Past and Present Biomineralization Processes. Considerations about the Carbonate Cycle. IUCN – COE Workshop, 15–16 November 1993, Monaco. Bulletin de l’Institut océanographique, Monaco, numéro special 13, 61–117.

Show in context

Show in context The causes of these fluctuations have fed debates opposing two major models: (i) one involving biotic causes suggests that grazing by Metazoans induced the decline of microbialites (Walter and Heys, 1985), and (ii) a second “abiotic” model proposes that changes in the chemical composition of the ocean were responsible for microbialite decline (Fischer, 1965; Kempe and Kaźmierczak, 1994; Peters et al., 2017).

View in article

Léveillé, R.J., Longstaffe, F.J., Fyfe, W.S. (2007) An isotopic and geochemical study of carbonate-clay mineralization in basaltic caves: abiotic versus microbial processes. Geobiology 5, 235–249. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1472-4669.2007.00109.x

Show in context

Show in context In two others (Kauai caves, Hawaii), microbialites formed on cave walls in freshwater seeping out of basalts and may experience significant chemical variations by evaporation and CO2 degassing (Léveillé et al., 2007).

View in article

Lim, D.S.S., Laval, B.E., Slater, G., Antoniades, D., Forrest, A.L., et al. (2009) Limnology of Pavilion Lake, B. C., Canada – Characterization of a microbialite forming environment. Fundamental and Applied Limnology/Archiv für Hydrobiologie 173, 329–351. https://doi.org/10.1127/1863-9135/2009/0173-0329

Show in context

Show in context For Lake Kelly, none of the several available measurements were saturated with ACC but it was reported that microbialites may no longer actively form (Lim et al., 2009).

View in article

Mackey, T.J., Sumner, D.Y., Hawes, I., Leidman, S.Z., Andersen, D.T., Jungblut, A.D. (2018) Stromatolite records of environmental change in perennially ice-covered Lake Joyce, McMurdo Dry Valleys, Antarctica. Biogeochemistry 137, 73–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-017-0402-1

Show in context

Show in context For example, Lakes Joyce and Hoare (Antarctica) have chemically stratified waters, and microbialites form at depths where DIC water content rises (Mackey et al., 2018).

View in article

Mergelsberg, S.T., De Yoreo, J.J., Miller, Q.R.S., Michel, F.M., Ulrich, R.N., Dove, P.M. (2020) Metastable solubility and local structure of amorphous calcium carbonate (ACC). Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 289, 196–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2020.06.030

Show in context

Show in context Indeed, the solubility of ACC increases with the Mg content (Mergelsberg et al., 2020).

View in article

Muller, E., Ader, M., Aloisi, G., Bougeault, C., Durlet, C., et al. (2022) Successive Modes of Carbonate Precipitation in Microbialites along the Hydrothermal Spring of La Salsa in Laguna Pastos Grandes (Bolivian Altiplano). Geosciences 12, 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences12020088

Show in context

Show in context Microbialites form when water reaches saturation with ACC (Muller et al., 2022).

View in article

Pecoraino, G., D’Alessandro, W., Inguaggiato, S. (2015) The Other Side of the Coin: Geochemistry of Alkaline Lakes in Volcanic Areas. In: Rouwet, D., Christenson, B., Tassi, F., Vandemeulebrouck, J. (Eds.) Volcanic Lakes. Advances in Volcanology, Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 219–237. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-36833-2_9

Show in context

Show in context In many cases, evaporation is a major driver for concentrating solutions and achieving high saturation with CaCO3 (Pecoraino et al., 2015).

View in article

Peters, S.E., Husson, J.M., Wilcots, J. (2017) The rise and fall of stromatolites in shallow marine environments. Geology 45, 487–490. https://doi.org/10.1130/G38931.1

Show in context

Show in context The causes of these fluctuations have fed debates opposing two major models: (i) one involving biotic causes suggests that grazing by Metazoans induced the decline of microbialites (Walter and Heys, 1985), and (ii) a second “abiotic” model proposes that changes in the chemical composition of the ocean were responsible for microbialite decline (Fischer, 1965; Kempe and Kaźmierczak, 1994; Peters et al., 2017).

View in article

Pietzsch, R., Tosca, N.J., Gomes, J.P., Roest-Ellis, S., Sartorato, A.C.L., Tonietto, S.N. (2022) The role of phosphate on non-skeletal carbonate production in a Cretaceous alkaline lake. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 317, 365–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2021.09.032

Show in context

Show in context Recently, Pietzsch et al. (2022), suggested that in some alkaline lakes, orthophosphate concentrations are high and inhibit crystalline anhydrous CaCO3 precipitation, allowing the onset of saturation levels as high as the solubility of ACC.

View in article

Pulido-Villena, E., Reche, I., Morales-Baquero, R. (2006) Significance of atmospheric inputs of calcium over the southwestern Mediterranean region: High mountain lakes as tools for detection. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 20, GB2012. https://doi.org/10.1029/2005GB002662

Show in context

Show in context Aqueous alkaline environments are fed by fluxes of Ca2+ and HCO3− ions, e.g., from water-rock interactions, and/or atmospheric inputs (Pulido-Villena et al., 2006).

View in article

Shapley, M.D., Ito, E., Donovan, J.J. (2005) Authigenic calcium carbonate flux in groundwater-controlled lakes: Implications for lacustrine paleoclimate records. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 69, 2517–2533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2004.12.001

Show in context

Show in context This generally does not directly create high saturation conditions, except when locally, e.g., Ca2+-rich groundwater outflows in high DIC lakes such as in Lake Van (Shapley et al., 2005).

View in article

Walter, M.R., Heys, G.R. (1985) Links between the rise of the metazoa and the decline of stromatolites. Precambrian Research 29, 149–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/0301-9268(85)90066-X

Show in context

Show in context The causes of these fluctuations have fed debates opposing two major models: (i) one involving biotic causes suggests that grazing by Metazoans induced the decline of microbialites (Walter and Heys, 1985), and (ii) a second “abiotic” model proposes that changes in the chemical composition of the ocean were responsible for microbialite decline (Fischer, 1965; Kempe and Kaźmierczak, 1994; Peters et al., 2017).

View in article

Weyhenmeyer, G.A., Hartmann, J., Hessen, D.O., Kopáček, J., Hejzlar, J., et al. (2019) Widespread diminishing anthropogenic effects on calcium in freshwaters. Scientific Reports 9, 10450. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-46838-w

Show in context

Show in context The Global Lake Ecological Observatory Network (GLEON) database compiles 105,678 samples from 6422 North European lakes with only temperature, pH, DIC and Ca2+ concentrations as physico-chemical parameters (Weyhenmeyer et al., 2019; see Supplementary Information).

View in article

Zeyen, N., Benzerara, K., Beyssac, O., Daval, D., Muller, E., et al. (2021) Integrative analysis of the mineralogical and chemical composition of modern microbialites from ten Mexican lakes: What do we learn about their formation? Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 305, 148–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2021.04.030

Show in context

Show in context However, only a few meta-analyses gathering some of these data provide a broader, statistical overview (e.g., Zeyen et al., 2021).

View in article

More recently, the same observation was done by Zeyen et al. (2021) in microbialite-hosting lakes in Mexico, who suggested ACC as an alternative precursor.

View in article

top

Supplementary Information

The Supplementary Information includes:

Download Table S-1 (xlsx)

Download Table S-2 (xlsx)

Download the Supplementary Information (PDF)

Figures

Figure 1 Plot of the log of the activities of CO32− vs. Ca2+ for 102 microbialite-hosting environments. Solubility lines (dashed lines) are reported for calcite (logKs = −8.48), aragonite (logKs = −8.34), monohydrocalcite (MHC; logKs = −7.6), vaterite (De Visscher and Vanderdeelen, 2003

De Visscher, A., Vanderdeelen, J. (2003) Estimation of the Solubility Constant of Calcite, Aragonite, and Vaterite at 25°C Based on Primary Data Using the Pitzer Ion Interaction Approach. Monatshefte für Chemie/Chemical Monthly 134, 769–775. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00706-002-0587-3

), ACC1 as reported by Kellermeier et al. (2014Kellermeier, M., Picker, A., Kempter, A., Cölfen, H., Gebauer, D. (2014) A Straightforward Treatment of Activity in Aqueous CaCO3 Solutions and the Consequences for Nucleation Theory. Advanced Materials 26, 752–757. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201303643

; logKs = −7.63) and ACC2 as reported by Brečević and Nielsen (1989Brečević, L., Nielsen, A.E. (1989) Solubility of amorphous calcium carbonate. Journal of Crystal Growth 98, 504–510. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-0248(89)90168-1

; logKs = −6.39). Only mean values are provided for each environment by a diamond. Green diamonds correspond to siliceous microbialites; red diamond corresponds to a clayey microbialite. Black diamonds correspond to environments saturated and oversaturated with ACC1 and/or vaterite; grey diamonds correspond to environments undersaturated with vaterite. The grey shaded zone highlights a 95 % confidence interval on the saturation values of microbialite-hosting environments with respect to ACC1/MHC.

Figure 2 Comparison of the microbialite-hosting environments and lakes in the EDI and GLEON databases. Compared distributions are (a) the log [Ca2+(mM)], (b) the log [HCO3− + CO32− (mM)] and (c) the pH of the microbialite-hosting environments (black bars) and the EDI and GLEON databases (grey or blue surface). Ca2+ activities were calculated using all major ion concentrations in the EDI database, whereas they were approximated to concentrations in the GLEON database. Errors due to this approximation are estimated to be minor (Fig. S-7). (d) Correlation circle from the global PCA of the physico-chemical parameters of EDI lakes and microbialite solutions. The logarithms of the activities and DIC were used. The colours correspond to those used to differentiate the principal components on the microbialite-hosting environments PCA (Fig. S-4). (e) Plot of all aqueous environments hosting microbialites (red dots) and from the EDI database (black and grey dots) along the two main dimensions of the ACP.

Figure 3 Plot of the activity of CO32− vs. Ca2+ for all lakes from the EDI (blue diamonds), GLEON (grey diamonds) and microbialite-hosting environments (yellow diamonds) datasets. Solubility lines of aragonite, calcite, monohydrocalcite and ACC are the same as in Figure 1.